Abstract

Tropical hunting studies that focus on tracking – how signs are interpreted – are rarely done if at all. This paper provides a preliminary sketch of the tracking strategies and knowledge of Batek of Malaysia. Studies of hunter-gatherer tracking rely heavily on Liebenberg’s carefully observed documentation of San tracking, enriched by his own scientific expertise in faunal behavior. Of the three levels of tracking he mentions, simple tracking is unreliable for the Batek, simply because of the nature of tropical forests. The default mode is systematic tracking, carefully gathering information, and piecing together a multisensorial picture of where prey is to be found. Their visual, auditory, and olfactory acuity is exceptional and so is their vocabulary for expressing these states. Tracking for Batek is not limited to the interpretation of tracks, or, rather, the notion of tracks needs to be broadened, to include tracks that cannot be seen, but can be heard and smelt. Tracking is about multisensory engagement in the needs of the moment and deploying the skills to decide what is and is not relevant information. It is about performance.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

This paper sets out, in a preliminary way, how tracking is done in the tropical forest, specifically by Batek hunter-gatherers in Pahang, Malaysia. While it is reasonable to assume that successful hunters are expert trackers of prey, tropical hunting studies that focus on tracking – how signs are interpreted – are rarely done if at all. Hunting ethnographies do give some attention to how various game animals are tracked or the spoors characteristic of particular animals (e.g., Puri 1997, 2005; Sillitoe 2003), but do not generally take tracking as their primary interest. For example, Gardner (2006: 39–41) provides an excellent account of a wild boar hunt, which includes some vivid imagery of how Paliyan men tracked, but does not elaborate on the subject. Anthropological attention has been towards hunting strategies and the products of the hunt rather than how the animals are found (e.g., Bulmer 1968; Dwyer 1974; Griffin 1984; Hayashi 2008). The purpose of this paper is to fill this lacuna.

Tracking has been described as the origin of science (Liebenberg 1990). It creatively combines empirical knowledge with imaginative hypothesis-building. Expert trackers have the spatial orientation to navigate along paths and are always on the lookout for signs of where to go next. They are also ready to be surprised: to respond to new and unpredictable situations and change plans as information changes. They do not just follow obvious tracks and traces but draw from prior knowledge to plan and anticipate directions. This knowledge is also based on that of other group members, which is often shared through storytelling (see Biesele Chap. 20). The skill to interpret comes therefore from shared experience, as discoveries and encounters are discussed and odd conjunctures of space, time, and sign are debated. As anthropologists argue, much of this knowledge is not solely the product of individual skill and experience, but must be interpreted through shared cultural idioms (Hutchins 1995; Widlok 1997; see Biesele Chap. 20).

Anthropologists have either been experienced hunters or become apprentice hunters in the field (Aporta 2009; Biesele and Barclay 2001; Estioko-Griffin and Griffin 1981; Puri 2005). Much of this paper is based on conversations about hunting, animals, and tracking, especially with ʔeyDukec and ʔeyHagap, who are both expert trackers in middle age (the former is more often quoted in this paper, but the latter, who is older and more experienced, was present on many conversations; both are old friends of mine). Personally, I mainly experienced tracking incidentally while doing something else (over an observation period of 27 years). I have documented animal trails and tracks but not systematically inventoried them thus far. As I will show below, Batek tracking is less about reading tracks than about connecting the marks on the ground with perceptual data, and making associations between this evidence and what is known more generally about the landscape. As such, tracks are not “read” in the way that, say, one might pursue words on a page, one after another in linear fashion. I will return to this point below. Although it is relatively easy to write about Batek perceptual knowledge (Lye 2004: 150–156), the challenge is to examine how sensory data – sounds, scents, and sights – plays a part in activities like tracking. In this paper, I will attempt to sketch out some broad parameters of tracking knowledge.

Ethnographic Background

The Batek call themselves batɛk həp (people of the forest). Numbering some 1500–1600, they are among the score or so indigenous ethnic minorities of Peninsular Malaysia, the Orang Asli (“Original People” in Malay). Before large-scale logging and land transformation began in the early 1970s, the Batek territory was contiguously forested; Endicott (2000: 110) estimated that roughly two-thirds of that area is lost beyond regeneration. Taman Negara, the 4343-square-kilometre national park, mostly sits astride Batek territory (Lye 2011), which covers a sizeable area where the states of Pahang (where I have done all my work), Kelantan, and Terengganu meet (Fig. 18.1). The park is mostly covered in lowland tropical evergreen rainforest. In Pahang, where the population numbers 650–800, just over half spend the majority of their time in Taman Negara. Taman Negara remains the largest unbroken tract of forest available to all Batek, who are permitted to live there and travel in and out of the park at their will, but not to collect forest products, including fauna, for sale. They are regarded as the original inhabitants of the park but do not have an administrative role and are not consulted on management issues (Lye 2002). Conditions outside the park are variable due to logging and land conversion from the 1980s onwards. The most extreme effects are the irreversible conversion of previously intact forest into oil palm and rubber plantations and, in Terengganu, total obliteration of forestland for the Kenyir Dam reservoir.

Most of Batek everyday movement occurs in an undulating lowland forest environment, with forested foothills being their preferred ecological niche. GPS-derived data show that they conventionally place camps and settlements at around 100 m a.s.l. (but see below on hunting tracks). The traditional mode of dwelling in the forest is to live in a camp (hayʔ); these camps are connected by an extensive series of pathways (halbəw) that traverses over walking trails, rivers, and logging roads, in a topography marked by the alternation of land and water.

In 1990s Pahang, Batek moved from camp to camp (jok) on average every 2 weeks or so. Two or so settlements had already emerged, partially due to external influence or pressure, but most sub-groups were forest-bound and mobile. Settlement composition was much like the big camps that periodically appeared whenever prominent shamans called people to them, usually for ritual-making purposes. The largest group I documented had just over a hundred people passing through at various points, large by Batek standards, where the average group population was 36.2 (around 40–45 was the preferred size). Traditionally the pattern was for each group to travel within the bounds of a tributary system over the course of several months. After 3 or 4 months, roughly corresponding to the end of a season, camp groups would disband, and splinter groups moved to other river valleys, joining and forming groups anew. Now they alternate between mobility and sedentariness, i.e. between settlement and camp life. The number of settlements has increased since the 1990s, but the essential character of communities has not changed. Populations in camps and settlements still fluctuate sharply, and settlements continue to be like base camps in which to rest or store belongings before moving on to other pursuits (Lye 1997: 390–428).

Batek are highly egalitarian and strongly value personal autonomy. There is no political hierarchy, although there are nominal headmen (penghulu or batin) appointed by the Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA) to mediate between groups of Batek and the government.

The Batek’s economy seemingly encompasses a broad variety of options. It is characterized by flexible and opportunistic shifting from one suite of activities to another as conditions change (Endicott 1984). The main source of cash income, and the economic activity that seems to occupy the most time, is commercial extraction of forest products: primarily rattan (mainly Calamus sp.). Other products are collected according to demand. When opportunities arise, men may do some day labouring, and there is some casual agriculture (Lye 1997: 69–76), now increasing in importance. Full-blown agriculture was traditionally the least favoured of these activities. Those living close to the headquarters of Taman Negara are also heavily involved in tourism, both in hosting the visits of tour groups to their camps and settlements and in guiding and driving tourist boats.

Throughout the daily, seasonal, and annual changes in production activities, hunting and gathering of forest foods remain important, both as a preferred alternative to buying store-bought foods and as valued activities in their own right. These subsistence activities are also central symbols of cultural and gender identity. They have high cultural value. The Batek’s staple diet, when nothing else is available, is takop (wild yams, Dioscorea sp.): “the most important and reliable source of carbohydrates” (Endicott 1984: 33). Fruits (available seasonally) are probably the Batek’s favourite foods and can temporarily replace game in the diet. The forest also provides them with vegetables such as palm cabbage, honey which is available in abundance during the flowering season, and, of course, game animals (ʔay), of which more below.

Tracking Habitats

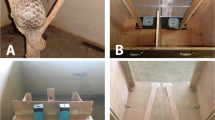

The habitat in which tracking occurs is a key variable. The lowland tropical forest is notorious for its low visibility. Not only is a high percentage of ambient light cut off before reaching the forest floor, views may be obscured by trees and other vegetation (Gell 1999: 239). Walking in the rainforest involves negotiating intimate spaces and an ever-changing mosaic of plant and animal communities. In foraging, one has to pick out tracks and traces of prey and plant foods in rather dim light. Of moving targets (e.g. birds in flight, squirrels darting along a tree limb, feeding creatures), all that is visible may be a quick flash of moving colour, the tip of a tail, an indistinct part of body, or, worse, the flutter of leaves or swaying of branches. Size, shape, and distinctive markings often cannot be reliably determined from the ground (Diamond 1991: 84; Ichikawa 1998: 109, 112), although animals may be identified from afar by their modes of locomotion, postures, and other characteristics (for example, whether they move in groups). An added complication is that animal sightings are relatively rare. In the daytime, little of the famed faunal diversity, other than inedible insects, bloodsucking leeches, and other invertebrates, as well as birds and other arboreal fauna, can be seen (Puri 1997: 150; Whitmore 1997: 58). Tracks on the ground are accordingly not plentiful. Having the skill to pick out salient details from the mass of wood and green matter is essential. Contrast this with tracking spoors in the arid environment of the Kalahari, where: “a tracker does not need exceptional eyesight. It is more important to know what to look for and where to look for it” (Liebenberg 1990: 71). Although knowing the what and the where is equally important to Batek, having good eyesight is critical to them (as demonstrated by a profusion of terms in their language for various kinds of seeing postures). The most fundamental is knowing how to look, what I call skillful looking. This was demonstrated by ʔeyDukec, who wore a head-mounted action camera as he walked a trail. Reviewing the video later, he pointed out: “This is how Batek search (kədap). We don’t look down at our feet. We stare left, right, upwards (diʔʔr ba-kiriʔ, ba-kanan, ba-ʔates). We take a quick look (tɔt), we look to the side (kihley). If we’re only looking for spoors, then we search the ground.” The Batek’s perspective is global, their eyes sweeping grandly around them, rarely resting on their feet. Furthermore, they must search knowledgeably. For example, they often trace animals’ pənyir (animal paths in the canopy; this word also refers to the flight paths of birds and other flying creatures) and know the trees that certain animals favor for their pənjɛs (sleeping trees), all of which presuppose a broad knowledge of the botanical environment too. On countless occasions, a walk will be brought to a sudden halt when someone in the group (men or women) casually espies something useful off-trail and goes off to harvest it. By far the bulk of environmental information comes from sounds (kəlɨη). The rainforest can be a noisy place, its cadences punctuated by distinct noises like the wəswas (great call) of female lar gibbons, the ramiη and cantum of siamangs, the pərikah of banded langurs, the bəbəp (ribbit) of giant Malaysian frogs, the gərliη (drumming) of woodpeckers, and so on. Obviously, sounds travel farther than visual images and can convey a lot more information. For hunters, the first indication that prey is nearby comes with sound emissions (kəηlɨη “to emit sounds”). ʔeyDukec explained this: “When we hear the sounds (of game animals) stationary in a placeFootnote 1, we go there, go towards the sounds. If the sounds have died down, we circle around. Walk round and round looking for the animal [see Fig. 18.2]. If we’re close and the sounds have died and the animal isn’t coming, that’s it.”

This reliance on sounds has been described for other forest peoples. For Mbuti of the Ituri Forest, Ichikawa (1998: 109) found that they “often could not identify the captured birds by their figure alone, but immediately identified them when the birds emitted their peculiar calls.” Gell’s comment that Umeda of New Guinea on their forest treks tended to use their “ever-receptive ears” to survey the far-off while keeping their eyes focused on the nearby is—with modification—a fitting description of Batek habits too (Gell 1999:239).

In like vein, I found that Batek were distinctly less interested (and more likely to make mistakes) in identifying birds from images, but became very alert and discriminating when they listened to audio recordings of the same species. Gell’s comment that Umeda of New Guinea on their forest treks tended to use their “ever-receptive ears” to survey the far-off while keeping their eyes focused on the nearby is – with modification – a fitting description of Batek habits too (Gell 1999: 239).

Hunting, Animals, Tracks

Animals have an honoured place in Batek imagination; they are, like many hunters (e.g. see, Nelson 1983), enraptured by animals, first-rate observers of and intellectually stimulated by animal appearances, habits, and behavior. They talk about animals often, telling stories, sharing observations, and asking questions of each other. The sounds of fauna are a constant hum in the background, and most Batek have phenomenally sharp ears. Invariably Batek will hear faint sounds (sounds that are bəʔabey-ʔabey or so faint that one cannot tell what they are) long before I am aware of them. Recordings of animal sounds are popular. Once in 1996, I recorded the calls of a lar gibbon moving close to camp; the Batek repeatedly asked to listen to it. One young man said the recording made him haʔip (yearn). When listening to playbacks of recorded sounds (of, say, the songs of gibbons), Batek will point out the sounds of other creatures captured in the recording and even how the animals were positioned relative to each other. For hunters, hearing the sounds of game provokes desire: as I was told, mɨʔ haran mɨʔm haluh mɨʔm jit mɨʔm rɛɲ (we feel the desire to shoot, to capture, and to eat). However, Batek interest in animals goes beyond satisfying gastronomical needs.

The general Batek term for hunting is sam. Under this broad category, the prototypical hunting method is to shoot (haluh) with the blowpipe (bəlaw), which is used to target arboreal game (Endicott 1974: 64–65; see Fig. 18.3).Footnote 2 Among Batek in 1970s Kelantan, Endicott estimated that blowpipe-hunting accounted for 68% of the time spent hunting and 71% of the game brought in (1979: 9). Hunting tracks generally follow ridge paths; elevations are higher than normal, averaging from 113 m a.s.l. to 557 m a.s.l. (as recorded thus far with GPS receivers). Normally hunts last from 5 to 7 h, though successful hunters might be detained into the night hours cooking the meat in the forest before trekking home (to lighten their loads). The primary targets are langurs (kaldus “banded langur, Presbytis femoralis” and talok “dusky langur, Trachypithecus obscurus”), and macaques (bawac “pigtailed macaque, Macaca nemestrina” and jəlew “long-tailed macaque, Macaca fascicularis”). Gibbons (kəboη “lar gibbon, Hylobates lar” and batẽw “siamang, Symphalangus syndactylus”) may also be hunted, but rarely. Other tree-dwellers like civet cats (viverrids), shrews, squirrels, and birds can also be captured in this way.

Blowpipe-hunting may be planned or fortuitous. When a hunter goes out, he will have the intention to hunt, but the choice of prey depends on what he finds there.Footnote 3 Once game is sighted but still elusive, hunters may stand still, head raised (bilay) far up (jɨlkok), studying the treetops (pratiʔ, Malay perhati “to look in detail”). Sometimes a place will be jaʔɛl, where animals are wary of humans and will flee on sight.Footnote 4 Under ideal conditions, the hunters must learn to stalk or creep (pədep) in such a way that they don’t reveal themselves. These stopovers (Guèze and Napitupulu 2017), when hunters stalk, can last from 10 min to just beyond an hour (as recorded by GPS receivers). Stopovers are defined as “areas where the density of track points is higher” (Guèze and Napitupulu 2017: 46), when hunters are detained by sight or sound of game. If they do sight game, and release the dart, the quarry does not die immediately and may escape successfully. If game is high beyond the range of the blowpipe, hunters may lure the animals (sensu Bulmer 1968) by making decoy calls through sound mimicry, drumming on the quiver, whistling with leaves, etc. If the animal has moved on, so do they. Hunters do not habitually chase the animals, though they may linger, waiting for wounded game to fall.

On other occasions, they may be lucky to capture an animal like kaldus when it descends from the treetop to drink or feed on snails and shrimps on side streams. ʔeyMantɔr remembered once:

[The kaldus] went upstream, I was on walking on land. I saw it. Slowly I crept up on it. It was sitting on an old piece of wood; its hand left an impression, like this [gesturing]. It had come down for food. It moved to another piece of wood to feed then climbed back up. I shot it. The shot landed.

Such animals are always in motion, whether on the treetops or (for some species) darting from tree to ground and up again, and therefore are not ambushed. I imagine that good hunters know how to select their trails to maximize their chances of such encounters, though thus far they’ve been too modest to admit to it. Arboreal hunting primarily requires knowledge of animal habits and their sounds and odours (the Batek most often mention urine), while the impressions the animals leave on the ground are extremely faint. Failure to procure (pawɛs) has been variously attributed to poor eyesight, hunters not knowing how to stalk and revealing themselves to game too soon, the dart poison had been weakened by age or contamination, or some happenstance of luck.Footnote 5

The precursor to blowpipe-hunting is catapult-shooting (Lye 1997: 367). All the hunters I’ve ever asked mentioned that they first learnt their skills playing with catapults as boys. Even today, the sight of boys and girls with catapults is pervasive everywhere. Their targets (often successful) are birds and, as they grow and begin practicing with blowpipes, squirrels. Catapults are an apt practice for the real thing: they learn to study the treetops, learn about the behavior of (avi)fauna, and practice eye-hand coordination, stealth, and how to stalk successfully.

Terrestrial hunting (primarily though not exclusively of deer) may be done with a spear (juliw), and some hunters are renowned for their success with it. The traditional Batek hunters would move camp with both a spear and a blowpipe, using either one depending on need. But while only the men use the blowpipe, women can use the spear too (I have listened to several enthusiastic accounts by women of how they plunged the spear into this or that animal). Other hunting methods (which women are also skilled at) include chasing and clubbing an animal with a machete or whatever else is available; digging up or luring from burrows, bamboos, or tree hollows with smoke or some other method; and, very rarely, setting traps and springes. Most of such hunts may be fortuitous encounters or planned when tracks of the animals are spotted (or their sounds heard). For swamp or riverine turtles and tortoises, they may head towards a likely spot, just to try their luck, and then look for the animal’s tracks and traces. On one memorable (to me) occasion, we were passing a swamp when we saw a turtle; I scooped it up by hand and presented it to the camp as the product of my hard work and visual acuity. In general, Skeat’s summary of Orang Asli hunting techniques continues to apply (with some modification) to Batek:

the catholicity of their tastes necessitates at once a most thorough and accurate knowledge of the habits of the varied denizens of the jungle, and a considerable amount of ingenuity and mechanical skill in the contrivance of traps, pitfalls, springes, and nooses for securing their quarry, and this knowledge, skill, and ingenuity the wild races certainly possess in a very marked degree. (Skeat and Blagden 1906: 11)

The one class of animals Batek don’t hunt is the larger animals like seladang, rhinoceros, tigers, elephants, crocodiles, etc. (Endicott 1979; Rambo 1978). Wild pigs roughly belong in this category (in the sense that hunters don’t normally launch an intentional hunt for pigs) but may be speared if the opportunity presents itself. However, even for this class of rarely-to-never hunted animals, Batek possess a great deal of intelligence and always stop to inspect footmarks and other signs of presence (like the farrowing nest of a wild pig).

Batek more rarely or outrightly did not use other hunting methods that might necessitate persistent track recognition, like ambushing (e.g., Bulmer 1968; Puri 1997), flushing out game with dogs (Puri 1997), besetting (Bulmer 1968: 310–311), shooting with guns (Puri 1997), and driving animals to a restricted or enclosed area (Bulmer 1968: 311–312). They do recognize the utility of the fire drive (Bulmer 1968: 312), but to chase animals away rather than to draw them in; for example, once they used fire to drive elephants away from a settlement. In 1970s Kelantan, Batek claimed to have practiced ambushing of wild pigs, but they were never observed to do so (Endicott 1974: 67–68).

Encountering Forest Tracks

Let us visualize what kind of tracks (hal) we might find in the tropical forest, specifically along an undulating lowland forest path in Taman Negara National Park, where most Batek live. There are one or two big clumps of vegetative matter on the ground – an elephant was here just days ago. Hoof marks going off-trail may show that seladang or deer were browsing or passing through. A fallen tree across the way, once seen fresh, has dropped more twigs and branches, with pointy sticks jutting up from beneath the leaves. Farther down the trail, another trunk obstructs, but it has lain here for many years and looks like a shadow of its former tree-self, becoming an integral part of ground dynamics and an ecosystem in its own right; the trail neatly winds around it. In a low part of the trail are deep, sloppy marks in a wet patch of mud where pigs have wallowed. A constant buzzing of ambient sounds betrays their makers’ presence. Some bird- and cicada-sounds are recognizable; most sounds will remain obscure. Here and there is evidence of people walking ahead: footprints, skid marks, crushed leaves, holes dug deep, shallow, or wide, bent twigs, discarded palm leaves, cut sticks, blackened half-peels of fruit strewn along the ground, or the ashy remains of a wayside fire. Between these signs, there may be none at all, giving the illusion of walking along a remote and deserted jungle path.

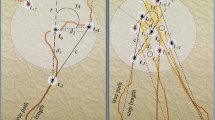

I first composed this passage for a paper on landscape marking (Lye 2016). What’s missing is what is above eye level. As discussed above, tracking (tɔt hal “to look at tracks” or kədap hal “to look for tracks”) for Batek, as for San in the Kalahari (Akira Takada, personal communication), is as much about studying the treetops as it is about what the ground reveals. Foraging trails invariably take the form of a loop (as confirmed by GPS representations collected since 2010 of fishing, hunting, and yam-digging expeditions), beginning with a purposeful trek along the main trail to the farthest point of the exploration area and then moving in the direction of home along the course of the same river that they had followed out. Hunting patterns follow the standard method of meandering from patch to patch, looking for the intended resource while monitoring landscape conditions along the way. Walking in the forest, hunters keep their ears open for even the slightest of sounds, from nearby to far-off, from faint slithers in the brush to the distinctive calls of key animals. Most important, they keep their eyes peeled on the treetops, alert to the jal (indicators) of animals, which are the tell-tale movement of leaves and branches that indicates that something is concealed there. If the animals are not making distinct sounds, jal may be the first “track” available to hunters.Footnote 6 Hunters who are attracted to game this way will move slowly, in a movement Batek call laηkah laηkah ɲan (step-step-stand) – two steps forwards, stand quietly, three steps backwards – as they try to keep the animal in sight while themselves remaining concealed.

As noted earlier, botanical knowledge is a necessary complement. Bulmer points out:

There is probably literally no limit to the knowledge of zoology and botany which is at least indirectly relevant or potentially useful to [a hunter]. To give but one example: a tree or plant may have no direct use for food or technology, but the ability to recognize it and the knowledge that its blossom, fruit, foliage, epiphytes or the insects which are found in it regularly provide food for certain kinds of birds or mammals, or that it regularly provides shelter from them, are highly relevant to the hunter. (1968: 316)

For example, the fruits of the fig trees jəriʔ (Ficusspp.; the name encompasses a number of species or sub-species) are favoured by hornbills, langurs, macaques, and gibbons alike, and occasionally these animals may congregate in the same tree, sometimes leading to interspecies fights. Another oft-mentioned feeding site is the təmjum tree (likely to be Artocarpus rigida): its resin is used as a binder for blowpipe darts as well as to darken the incised patterns on combs, while its fruits are favoured by animals. As animals feed, they may drop feces and fruits and other foliage on the ground, and it is these droppings that can point the way to a tracker. There are innumerable species of trees and palms that are useful in this way, which has not been comprehensively documented thus far. Beyond strictly utilitarian needs, Batek store an exemplary amount of information, which does not seem to have immediate uses. For example, they not only know about the ubiquitous fishtail palm gaseʔ (Caryota mitis; its fluff is used as tinder and it produces edible pith), they can distinguish it from the montane equivalent, jɨk (Caryotaspp.), while admitting that they never see jɨk in their territory (it is ubiquitous in the hilltops of my territory, in Penang). Liebenberg provides an explanation for this “excess” of knowledge, what I’ve (Lye 2004: 62) earlier attributed to the Batek’s broad-spectrum foraging:

Every animal, down to the smallest invertebrate that leaves a characteristic spoor is relevant to tracking. While hunters study animal behaviour far beyond their immediate utilitarian needs in hunting, even the most obscure detail may be used at some point in the future to interpret spoor. (1990: 88)

The odors (məniʔ) of animals is also important for tracking. In common with other Orang Asli cultures, olfaction is highly developed among Batek, and their language includes single-word terms to label the smells they encounter (more elaborated than in English). Like the Jahai, Batek have several basic odour terms, which “can be categorized along a pleasant-unpleasant dimension”, with the majority having unpleasant connotations (Burenhult and Majid 2011: 23). Importantly, the terms:

abstract away from the actual sources typically associated with them. So although a verb like ltpɨt [for Jahai] is prototypically used to describe the fragrant odors of flowers (e.g. Globba, Lantana sp.) and perfumes, any source whose odor approximates such a quality can be described with the same verb. (Burenhult and Majid 2011: 23)

Batek odour terms and their prototypical sources uncovered so far include the following:

-

haʔãt (to have a bad stench)Footnote 7

-

pəlʔãt (to have a smell like urine, dead leaves, and stale rice)

-

pəlʔɛη (to have a blood/fish/meat-like smell [Burenhult and Majid 2011: 23])

-

səʔol (to have a bad smell like blauwɛn, a species of wild mango)

-

cɨηas (to have a smell like curry or bones)

-

ηãt (to have a burnt smell) traηis (to have the smell of burnt fur [but see Rudge 2017: 137 for an alternative definition])

-

hapak (to have a musty smell, as of old clothes; a Malay loan)

-

mahũ (to have a raw fragrance like bamboo leaves or cigarettes)Footnote 8

-

ləʔɔm (to have a fragrance like coffee, fresh leaves, and fragrant durians)

-

həraʔum (to have the smell of food beginning to go bad)

Among these labels, pəlʔãt would seem most relevant to tracking, given the frequency that Batek mention the smell of animal urine, followed closely by pəlʔɛη, which is the olfactory quality associated with fish and the bearcat. However, it is not yet known how Batek conceptualize the smells of different animals, how the knowledge of smells assists in tracking and hunting, how odors are masked, and how hunters and animals manoeuvre around the reciprocity of odors. That the identification of smells is habitual was shown once. Some Batek men were walking outside my home in Penang when they smelt the urine of long-tailed macaque. Though the information was irrelevant to that moment (they were not hunting and will not hunt town-adapted animals), they stopped walking, discussed where the scent came from, and reconstructed the macaque’s movements down the hill: “it sleeps up there, and it’s gone down there”. One can imagine such reconstructions taking place on a real hunt, with the hunter not only placing the prey in relation to himself but entering into the perceptual world of the prey and its environmental affordances, including recognizing its likely pathways in the forest.

Simple, Systematic, and Speculative Tracking

If tracking is about the interpretation of signs, then those signs need to be defined differently. In a seminal study, Louis Liebenberg identifies three overlapping levels of tracking, simple, systematic, and speculative (see Lenssen-Erz and Pastoors Chap. 6).

Simple tracking involves:

following footprints in ideal tracking conditions where the prints are clear and easy to follow. (Liebenberg 1990: 29)

As described earlier, the tropical forest rarely affords “ideal tracking conditions”. Occasionally one may encounter distinct spoors in sand or hoof marks on a path after rainfall (see Fig. 18.4), but it’s not very long before the tracks disappear into the woods where they become obscured by vegetation. More often, there will be single or dual footprints, left by an animal on a patch of mud. ʔeyHagap (among others) considers the scaly anteater (man) the most difficult animal to track; it can be followed through the forest, but it tends to escape over riverside rocks and then out of sight.

Systematic tracking is the next level up from simple tracking, which involves:

the systematic gathering of information from signs, until a detailed indication is built up of what the animal was doing and where it was going” in conditions where “footprints are not obvious or easy to follow. (Liebenberg 1990: 29)

As the preceding discussion has shown, it seems that Batek are systematic trackers par excellence. In terrestrial tracking, tracking is less about interpreting what each print denotes, than using other evidence (such as impressions and discolorations) to identify the animal’s path (tǝnaηoh), like cinroη (a well-used animal path) and wɛs (a snaking trail made by fauna like snakes, deer, or millipedes) (for comparison with San classification of animal paths, see Takada 2016: 182–183). The Batek’s skill at spotting such discontinuities in the landscape leaves their ethnographer shaking her head in disbelief. For example, we were tracking in the Penangx National Park once when ʔeyDukec and ʔeyHagap spotted a tənaηoh on the side of the trail. It was a cinroη, confirmed when they brushed away the leaves to reveal the imprint of a pig’s cloven hoofs (see Fig. 18.5). In retrospect, I could see discolorations in the soil which indicated that pigs had habitually passed through – once the tracks were pointed out to me. Most people, I suspect, would walk by without noticing anything. The signs are too subtle, and the forest is full of signs.

But most of their tracking, as discussed earlier, is arboreal. They not only have to attend to what’s in the treetops; they have to connect that to the food that animals drop, to their characteristic smells and calls, to their knowledge of individual faunal behavior at different times, and to the wider forest milieu. Tracking is multisensorial for Batek, involving (at the very least) sight, sound, and smell and the knowledge that enables them to interpret what they encounter. It is not just a matter of seeing tracks and trying to figure out what Suzman (2017: 167) calls their “grammar”, “metre”, and “vocabulary”. Suzman was told by a Ju/’hoan man:

[t]racks were there for everybody to see…but to read them you had to understand why they were made. (2017: 167)

The activity of interpretation itself is multisensorial, involving both visible and non-visible evidence, overlaid with countless observations of human and nonhuman behavior.

The third level of tracking is speculative tracking, which is complementary to systematic tracking; this:

involves the creation of a working hypothesis on the basis of the initial interpretation of signs, a knowledge of animal behaviour and a knowledge of the terrain…With a hypothetical reconstruction of the animal’s activities in mind, trackers then look for signs where they expect to find them. The emphasis is primarily on speculation, looking for signs only to confirm or refute their expectations. (Liebenberg 1990: 29, 106)

The difference with systematic tracking is that in systematic tracking:

Trackers do not go beyond the evidence of signs and they do not conjecture possibilities which they have not experienced before. (Liebenberg 1990: 106)

Liebenberg suggests that trackers vary between systematic and speculative tracking according to the conditions of the hunt; by taking the risk of (say) ambushing animals at a place where they are expected to appear, trackers might shorten the hunt. Reportedly, San trackers excel at speculative tracking, using “a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning outsiders have yet to understand”. (Biesele and Barclay 2001: 70).

As hinted earlier, the best Batek hunters probably do track speculatively, using their knowledge of landscape geography in their selection of hunting paths. For example, they may use botanical knowledge to explore likely feeding sites when they set out to hunt, thus increasing their chances of encountering game. ʔeyDukec remembers that it was in 1993 (when I was in camp) that he first brought down multiple animals on a single hunt (a combination of langurs and macaques). Up until then, he could only manage to capture at most one animal per hunt. He claims he doesn’t know what changed. I would suggest that that’s the point where he was able to incorporate speculative tracking skills into his repertoire. Certainly, there’s a lot of interindividual variation in hunting success. Speculative tracking provides one way of explaining this variation. However, this needs much more confirmation from the Batek.

Discussion

Studies of hunter-gatherer tracking rely heavily on Liebenberg’s carefully observed documentation of San tracking, enriched by his own scientific expertise in faunal behavior. But the environment he worked in is very different from the tropical forests of the Batek. Visual markers are clearer or more legible in the arid environments of the Kalahari. However, wind and rain play their part, and all marks eventually vanish whether in arid environments, in snow (Aporta 2009), or in the tropical forest. The effective difference is that simple tracking is unreliable for the Batek, except for extremely large animals (like the elephant), which leave unmistakable traces of passage through the forest. The default mode is systematic tracking, carefully gathering information, and piecing together a multisensorial picture of where prey is to be found. These tracks may be sequential (for example, when a scent trail is followed by sounds and then visual markers) or convergent (for example, when trackers sniff droppings to determine whether they were left by langurs or gibbons). Their visual, auditory, and olfactory acuity is exceptional and so is their vocabulary for expressing these states. Tracking for Batek is not limited to the interpretation of tracks, or, rather, the notion of tracks needs to be broadened, to include tracks that cannot be seen, but can be heard and smelt. It might be more productive to think instead of traces rather than tracks (Thomas Widlok, personal communication).

What then of the association between “reading” and tracks? When a tracker like ʔeyDukec draws on his expertise in seeing, hearing, and smelling the traces of an animal, he is not reading tracks. For one thing, reading suggests that the tracker is only looking at/for visual evidence. Rather, trackers draw on sensory input to figure out what is going on around them. Tracking is about multisensory engagement in the needs of the moment and deploying the skills to decide what is and is not relevant information. Tracking is about performance. The situational context of every track is different depending on the animals encountered and the particular suite of traces they leave behind them. Similarly, every tracker—every performer—will bring a different set of skills and aptitudes to the task at hand.

This paper has approached tracking as cultural activity. By this is meant that tracking is learned, not innate, knowledge. Although adaptation is a partial reason for the Batek’s well-developed senses, expertise in tracking discernibly increases with age and experience, only to decline when faculties fail. In the case of the Batek, there is a broad stratum of knowledge about environmental signs and affordances, sightings, and events which all adults likely share, but there are subtleties, levels of expertise, which are more limited to those who regularly go to the forest and track. Only by following along on hunts (and other tracking-related activities) and being on hand when expert trackers are examining evidence does a novice learn how to do it, with secondary (derived) knowledge obtained verbally. This knowledge is visible in that it involves interpreting landscape traces, but much knowledge is tacit. Some kinds of knowledge are, if not esoteric, unlikely to be articulated out of context. For example, ʔeyDukec remembers that he was hunting with an older man when groups of gibbons sounded in the hillsides all around them, all at once; only then was he told that this was characteristic gibbon behavior for announcing rainfall (it did rain that afternoon). All this suggests that sedentarization and corresponding reluctance to hunt (both on the increase now) might pose a threat to Batek tracking knowledge.

Notes

- 1.

The original in Batek was kəjiη kəlɨη ηok kə-tun (hear the sounds sitting over there).

- 2.

When a hunter goes out, he might say yɛʔm sam (I’m going to hunt), but the corresponding term yɛʔm haluh (I’m going to shoot with the blowpipe) sounds rather odd and is never announced except in jest. This may due to the avoidance practices which the Batek share with many hunters (e.g. Puri 1997: 256–258 on the Penan Benalui).

- 3.

Hunts may also be stimulated by reports from other people. For example, to pənton is to tell others where one had recently encountered game. Obviously, anyone, hunters and non-hunters alike, can pənton. If the animal has been sighted, to pəltɔt (“to cause to see”) is to direct another person’s attention to it.

- 4.

This description is from ʔeyDuket and ʔeyHagap, who provided an exegesis of a video that I had shot of another man, ʔeyAlɔr, stalking prey.

- 5.

For both men and women, pawɛs is contrasted to bərguh (to be successful), while malaη and siyal are foraging failures attributed to some combination of ill-luck and human error.

- 6.

According to Alice Rudge, jal means both visual and sonic indicator; its meaning is multi-sensory (2017: 189).

- 7.

The prototypical source of haʔãt is shit. Once I asked what shit smells like. There was total (amused) agreement: that just smells haʔãt;

- 8.

This might be a loan of Malay maung. However, the meanings are completely different. Maung in Malay means a smell that induces vomit, whereas Batek mahũη has more pleasant connotations.

References

Aporta, C. (2009). The trail as home: Inuit and their Pan-Arctic network of routes. Human Ecology, 37(2), 131–146.

Biesele, M., & Barclay, S. (2001). Ju/’hoan women’s tracking knowledge and its contribution to their husbands’ hunting success. African Study Monographs, 26, 67–84.

Bulmer, R. (1968). The strategies of hunting in New Guinea. Oceania, 38(4), 302—318.

Burenhult, N., & Majid, A. (2011). Olfaction in Aslian ideology and language. Senses and Society, 6(1), 19—29.

Diamond, J. (1991). Interview techniques in ethnobiology. In A. Pawley (Ed.), Man and a half: Essays in Pacific anthropology and ethnobiology in honour of Ralph Bulmer (pp. 83—86). Auckland: The Polynesian Society.

Dwyer, P. D. (1974). The price of protein: 500 hours of hunting in the New Guinea highlands. Oceania, 44, 278—293.

Endicott, K. (1974). Batek Negrito economy and social organization. Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Endicott, K. (1979). The hunting methods of the Batek Negritos of Malaysia: A problem of alternatives. Canberra Anthropology, 2(2), 7—22.

Endicott, K. (1984). The economy of the Batek of Malaysia: Annual and historical perspectives. Research in Economic Anthropology, 6, 29—52.

Endicott, K. (2000). The Batek of Malaysia. In L. Sponsel (Ed.), Endangered peoples of Southeast and East Asia: Struggles to survive and thrive (pp. 101–122). Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Estioko-Griffin, A., & Griffin, P. B. (1981). Woman the hunter: The Agta. In F. Dahlberg (Ed.), Woman the gatherer (pp. 121—153). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gardner, P. M. (2006). Journeys to the edge: In the footsteps of an anthropologist. Columbia and. London: University of Missouri Press.

Gell, A. (1999). The art of anthropology: Essays and diagrams (London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology Monograph) (Vol. 67). London: Athlone.

Griffin, P. B. (1984). Forager resource and land use in the humid tropics: The Agta of northeastern Luzon, Philippines. In C. Schrire (Ed.), Past and present in hunter-gatherer studie (pp. 95—121). London: Academic.

Gueze, M., & Napitupulu, L. (2017). Trailing forest uses among the Punan Tubu of North Kalimantan, Indonesia. In V. Reyes-García & A. Pyhälä (Eds.), Hunter-gatherers in a changing world (pp. 41—58). Cham: Springer.

Hayashi, K. (2008). Hunting activities in forest camps among the Baka hunter-gatherers of southeastern Cameroon. African Study Monographs, 29(2), 73—92.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ichikawa, M. (1998). The birds as indicators of the invisible world: Ethno-ornithology of the Mbuti hunter-gatherers. African Study Monographs, Suppl. 25, 105—121.

Liebenberg, L. (1990). The art of tracking: The origin of science. Cape Town: David Philip.

Lye, T. P. (1997). Knowledge, forest, and hunter-gatherer movement: The Batek of Pahang, Malaysia. Ph.D. dissertation. Honolulu: Department of Anthropology, University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

Lye, T. P. (2002). Forest peoples, conservation boundaries, and the problem of ‘modernity’ in Malaysia. In G. Benjamin & C. Chou (Eds.), Tribal communities in the Malay world: Historical, cultural and social perspectives (pp. 160—184). Leiden/Singapore: IIAS/ISEAS.

Lye, T. P. (2004). Changing pathways: Forest degradation and the Batek of Pahang, Malaysia. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Lye, T. P. (2011). The wild and the tame in protected areas management, Peninsular Malaysia. In M. R. Dove, P. S. Sajise, & A. A. Doolittle (Eds.), Complicating conservation in Southeast Asia: Beyond the sacred forest (pp. 37—61). Durham: Duke University Press.

Lye, T. P. (2016). Signaling presence: How Batek and Penan hunter-gatherers in Malaysia mark the landscape. In W. Lovis & R. Whallon (Eds.), Marking the land: Hunter-gatherer creation of meaning in their environment (pp. 231—260). Oxford: Routledge.

Nelson, R. K. (1983). Make prayers to the raven: A Koyukon view of the Northern Forest. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Puri, R. K. (1997). Hunting knowledge of the Penan Benalui. Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

Puri, R. K. (2005). Deadly dances in the Bornean rainforest: hunting knowledge of the Penan Benalui (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- en Volkendunde 222). Leiden: KITLV Press.

Rambo, A. (1978). Bows, blowpipes and blunderbusses: Ecological implications of weapons change among the Malaysian Negritos. The Malaysian Nature Journal, 32, 209—216.

Rudge, A. (2017). Sound and socio-aesthetics among the Batek hunter-gatherers of Pahang State. Malaysia. Ph.D. dissertation: University College London, London.

Sillitoe, P. (2003). Managing animals in New Guinea: Preying the game in the highlands. London: Routledge.

Skeat, W. W., & Blagden, C. O. (1906). Pagan races of the Malay Peninsula (Vol. 1). London: Macmillan.

Suzman, J. (2017). Affluence without abundance: The disappearing world of the Bushmen. New York/London: Bloomsbury.

Takada, A. (2016). Unfolding cultural meanings: Wayfinding practices among the San of the Central Kalahari. In W. Lovis & R. Whallon (Eds.), Marking the land: hunter-gatherer creation of meaning in their environment (pp. 180–200). Oxford: Routledge.

Whitmore, T. C. (1997). An introduction to tropical rain forests. Oxford: Clarendon. Rev. ed.

Widlok, T. (1997). Orientation in the wild: The shared cognition of Hai//om bushpeople. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 3(1), 317–332.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following institutions for fieldwork support: the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, the East-West Center, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Japan Society for Promotion of Science, Universiti Sains Malaysia, the National Geographic Foundation, the Habitat Foundation, and IdeaWild. Thanks to the editors of this volume Andreas Pastoors and Tilman Lenssen-Erz for inviting me to the Reading Prehistoric Tracks workshop in Cologne, and for patient editing. Many thanks to Thomas Widlok, Edmond Dounias, Kirk Endicott, Alice Rudge, Peter Gardner, Takada Akira, and Bion Griffin for stimulating chat and useful feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Most of all, I thank the Batek, especially ʔeyDukec and ʔeyHagap, for taking me along on forest treks and taking seriously my never-ending questions about animals, trails, tracks, sounds, and smells.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lye, TP. (2021). Tracking with Batek Hunter-Gatherers of Malaysia. In: Pastoors, A., Lenssen-Erz, T. (eds) Reading Prehistoric Human Tracks. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60406-6_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60406-6_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-60405-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-60406-6

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)