Abstract

Citizen science practices have different frames to general scientific research – the adoption of participatory methods in research design has long been pursued in citizen science projects. The citizen science research design process should be inclusive, flexible, and adaptive in all its stages, from research question formulation to evidence-based collective results. Some citizen science initiatives adopt strategies that include co-creation techniques and methodologies from a wide variety of disciplines and practices. In this sense, the will to collaborate between researchers and other stakeholders is not new. It is traditionally found in public participation in science, including participatory action research (PAR) and the involvement of civil society organisations (CSOs) in research, as well as in mediatory structures, such as science shops. This chapter critically reviews methodologies, techniques, skills, and participation based on experiences of civic involvement and co-creation in research and discusses their limitations and potential improvements. Our focus is on the reflexivity approach and infrastructure needed to design citizen science projects, as well as associated key roles. Existing tools that can be used to enhance and improve citizen participation at each stage of the research process will also be explored. We conclude with a series of reflections on participatory practices.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Citizen science projects and initiatives allow non-professional researchers to contribute to a variety of usually large-scale research processes. The collaboration process is often facilitated by information and communication technologies (ICT). However, a series of questions must be considered about the participatory design of research processes. This goes beyond a purely contributory vision of citizen science – that is, of data collection by citizens. Lessons can be drawn from a long tradition of related practices such as participatory action research (PAR) and the involvement of civil society organisations (CSOs) in research (see also Göbel et al., this volume, Chap. 17). This chapter discusses the importance of co-creation and participation in citizen science research and describes some existing projects and approaches. A range of research approaches are considered, including participatory science, open science perspectives, ethics of collaboration, as well as alternative viewpoints. The case studies exemplify the involvement of a diversity of stakeholders in the design and execution of research initiatives and shed light on key issues of communication, participatory design techniques, and facilitation principles. The chapter aims to provide a series of methodological and participatory design principles to support the development of successful co-created and participatory citizen science initiatives in the future.

Articulating Citizen Co-creation in Research

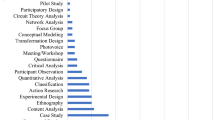

Over the past 30 years, the idea and practice of laypersons or representatives of civil society participating in processes of research and innovation has gained increasing significance. A milestone in this debate was Epstein’s study (1996) that demonstrated how AIDS activism in the USA had an important impact on the process of research, including setting the research agenda. The influence was effective with regard to research outcomes but also disruptive in relation to the scientific research process itself, by blurring the boundary between science and the public. In this sense, a vast number of studies have been carried out with respect to the role and impact of non-academics in the field of scientific research (Rabeharisoa and Callon 2004). A similar dynamic can be observed when involving individuals in the early stages of knowledge generation, where it is akin to the idea of open innovation (West and Bogers 2017). As participation of civil society actors is seen as a key resource for improving processes of research and innovation, these debates are grouped under the terms upstream engagement (Escobar 2014) or even citizen science (Irwin 2002). All these ideas represent typologies that highlight interaction between research (or researchers) and civil society actors as the core feature (Fig. 11.1).

Traditionally, literature on research design focuses on how to practically define a scientific process. Recently, this has moved on to how to implement, for example, more visual or digital methods (Rogers 2013); however, this is usually from the perspective of the principal researcher as the main decision-maker. This also applies in scientific teams, where crucial research design steps are usually informally negotiated. There is significant literature discussing collaboration between civil society as well as CSOs and the scientific community. This literature, mainly based on the analysis of case studies, challenges specific aspects of collaborations, such as the ‘expert–lay divide’ and the issue of undone science – which refers to areas of research sometimes left unfunded, incomplete, or ignored, for not being of interest to the political and economic elites but that social movements and CSOs identify as worthy of investigation.

Some authors suggest that increasing the involvement of CSOs in research corresponds with improved research results, especially with regard to embedding contexts and wider society (Hickey et al. 2018). In parallel, originating in the design sphere (Sanders and Stappers 2014), co-creation approaches are increasingly being extended to the political, social, cultural, and scientific spheres, in line with increasing public participation in collective decision-making processes. Regarding citizen science practices, for example, in the context of health-related and environmental science, fully co-created projects are still rare: the majority of citizen science projects rely on participation only for the collection, and sometimes the analysis, of large-scale observations, in order to overcome the capacity of current research structures (Kullenberg and Kasperowski 2016). While not all citizen science projects are intended to achieve in-depth public participation, evidence suggests that research results can be significantly shaped by the degree and quality of public participation in project design (Shirk et al. 2012). At the same time, recent studies highlight a motivational framework for volunteers that exceeds data collection, where the wider social impact and cognitive, affective, social, behavioural, and motivational dimensions are all relevant (Phillips et al. 2019).

The motivational framework also relates to participatory action research (PAR) and other community-based research practices, where a diversity of non-professional and nonacademic researchers can be fully involved in the investigation process. Participants can then collaborate with researchers in practical or pressing issues at the local level, representing the needs of different organisations and communities (Reason and Bradbury 2001). Citizens or CSOs can also take the initiative and lead the research in collaboration with the researchers, as seen in some recent citizen science projects. Here, citizens are not considered qualified research assistants but rather coresearchers; they are able to design and implement, jointly with scientists or in an autonomous way, valid and robust research processes (Kimura and Kinchy 2016). In order to implement these approaches, inclusive processes must be used in conjunction with the development and adaptation of robust methodologies, allowing for the social concerns of citizens and local communities to be specified and expressed (Senabre Hidalgo et al. 2018). This requires integrating these problems and challenges into the research cycle at its onset and then facilitating the participation of groups of citizens or CSOs in all phases of the research process. It also demands adequate participatory infrastructures, for example, science shops, as intermediaries between civil society groups (e.g. trade unions, consumer associations, non-profit organisations, social groups, environmentalists, consumers, residents’ associations, etc.) and the scientific community.

Throughout the research process, a participatory and social impact-oriented research cycle needs to follow specific iterative and reflexive steps from a co-creation and participative perspective (Fig. 11.2).

The four case studies that follow reflect how co-creative and participatory processes unfold in different social contexts, local settings, and communities of practice.

Case Study 1: OpenSystems – Participatory Design in Citizen Social Science

An emerging practice, termed citizen social science (Kythreotis et al. 2019), serves as our first case study to provide insights on whether and how co-creation should be adopted in research design. Citizen social science (see also Albert et al., this volume, Chap. 7) can be understood as co-created research that builds on participatory social sciences approaches or social concerns expressed by diverse groups of citizens (Bonhoure et al. 2019).

Citizen social science is intended to facilitate participants’ contribution to research. Their unique expertise comes from everyday experiences, including of their neighbourhoods, health (Cigarini et al. 2018), gender discrimination (Cigarini et al. 2020), and climate action (Vicens et al. 2018). Following a horizontal approach and a distributed expertise model (Nowotny 2003), participants can be considered competent in-the-field experts and therefore able to produce socially robust knowledge.

In order to enact co-creation in citizen social science, it is key to establish a process and associated tools that combine materials and instructions, in order to facilitate the participatory design of projects (Senabre Hidalgo et al. 2018). OpenSystems developed tools for knowledge generation, each associated with a reflexive research stage (see Fig. 11.3). The tools were tested and refined during six co-creative processes using a series of activities based on alternate phases of divergence and convergence, a fundamental principle of research design (Sanders and Stappers 2014).

-

1.

The first sequence generates ideas and possibilities in a participatory way; the sequence of divergence is normally enacted through the formation of subgroups.

-

2.

In the second sequence, the participants jointly select options; the sequence of convergence is enacted through pooling and decision-making mechanisms, as reflected in Fig. 11.3.

-

3.

During the convergence steps, collective decision-making is achieved through dot-voting, or dotmocracy, and thermometers of concepts.

Accessibility was emphasised with the aim of making the tools clear and attractive to a diverse public. In particular, the visual language was kept as simple as possible, and easy-to-understand icons were used. Gamification strategies were also integrated, based on feedback from participant focus groups.

This approach to citizen social science was developed by OpenSystems from the Universitat de Barcelona in different research contexts. The first was STEM4youth, a project from the European Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (2016–2018) to encourage young people to study science and pursue technology careers. A series of co-creation experiences were organised to design citizen science projects with 4 groups of teenagers (128 teenagers in total) attending secondary schools in Barcelona, Spain, and Athens, Greece. The same approach was used in the project Neighbourhood Water, which engaged a group of youth members from the Itaca Association in early 2019. This association, located in the Collblanc-La Torrassa district in Barcelona (one of the most population dense and diverse in Europe), is aimed at providing youth social education. Finally, this co-creative strategy was used in the framework of a Barcelona Public Libraries Network initiative to reformulate the role of librarians and public libraries in local communities. Building on the idea of libraries as community hubs, librarians acted as mediators for a co-created research design, with a community of library users (45 on average) acting as coresearchers. Adopting these co-creative processes resulted in a number of behavioural projects being undertaken with engaged communities of citizen scientists (Perelló et al. 2012).

Case Study 2: Kubus Science Shop at Technische Universität Berlin (TUB)

Science shops provide independent, participatory research support and carry out scientific research in a wide range of disciplines. They are often, but not always, linked to or based in universities. If university based, research is often carried by students as part of their curriculum, under the supervision of the science shop staff and other associated university members (as in the Boutique des Sciences Lille Science Shop). Science shop facilitators are experts in the field of cultural translation and reflexive practices. Through their local, national, and international contacts, science shops provide a unique antenna function for society’s current and future demands on science.

Two of the most pressing issues of our time are the reduction of resource consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. The growing use of electronic equipment in everyday life and the waste derived from consumer goods result in significant social and environmental costs worldwide. The term throwaway society addresses this negligent, yet socially normalised, attitude towards resource consumption. On the other hand, cities are a focal point for social innovations, such as in the repair and do-it-yourself (DIY) movements (Frick et al. 2020), which offer a practical solution. Citizens can (re)gain the ability to handle their consumer goods competently and learn what they need to do in the event of either repair or programmed obsolescence. In this sense experts, hobbyists, and amateurs are all looking for solutions to global technological production and consumption problems. This can take place via specific online forums, or in face-to-face groups, such as repair cafes (Keiller and Charter 2016), FabLabs, hackerspaces, and makerspaces (Becker and Zacharias-Langhans 2014). In these social and technical contexts, it is important to generate robust knowledge about reduction in environmental impact as part of community empowerment (Scheumann and Becker 2014).

There are more than 40 such initiatives in Berlin alone. In 2015, Kubus, the Science Shop of Technische Universität Berlin (TUB), supported the founding of the Repair Café Brunnenviertel in the district of Wedding. In addition to meeting a shared need and interest in repairing electronic tools, hardware, and other types of machines, repair cafes are places where social networks can be strengthened and social capital can be developed (Keiller and Charter 2016). In this context, diverse communities emerge that can explicitly or implicitly promote a new appreciation of resources and their efficient use, quality, and longevity, encouraging sustainable consumption in the long term. Kubus initiated a collaboration between UTIL (the TUB Environmental Technology Integrated Course) and the Repair Café Brunnenviertel. They adopted a co-creative and participatory approach that sought to facilitate aspiring environmental engineers to provide life cycle assessments of CO2 savings, focusing on repair groups of 3–5 students each summer semester. Integrating university students and citizens from the repair community, the first group showcased their research results at the Repair Café Christmas party, providing concrete insights on how to evaluate CO2 savings. This type of research-based service learning (Becker et al. 2018), as part of a student-organised course, enables students to engage in transdisciplinary participatory research (Fig. 11.4).

With these practical experiences, Kubus allows a knowledge-based dialogue on teaching everyday skills and competences, which makes it possible to address the social responsibility of academic education on two levels: first, in the ‘here and now’ of pragmatic cooperation between students and civil society actors and, second, in the experiential education of aspiring engineers and scientists participating as students in these courses. Kubus sought to improve approaches to hands-on academic education. Their participatory approach helped students to self-organise explorative and research-oriented learning, encouraging them to present and discuss their project designs not only with their teachers but also with the repairer community.

Case Study 3: Procomuns – PAR and Co-creation of Public Policies

Procomuns, led by the Dimmons research group from the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (Spain), focused PAR on citizen participation in policymaking in the fields of social and solidarity economy and the platform economy. Procomuns was a 3-year explorative study, between 2016 and 2019, analysing how co-creation dynamics in the social sciences can contribute to the participatory definition of public policies and agendas in a local context. Project participants (more than 400 people from diverse backgrounds and perspectives) were involved in a co-creative policymaking process that resulted in 87 policy measures. The central topic of research was the platform economy (also called the sharing economy or the collaborative economy). This refers to the collaborative consumption and production of capital and labour among distributed groups supported by a digital platform. Examples range from shared vehicles to food delivery to home sharing. Several questions were raised about which public policies to adopt, and how policymaking with a citizen science approach can adapt to, take advantage of, and respond to the platform economy, its effects, and potential.

In this regard, the goal of Procomuns was threefold: first, to develop a state of the art on the topic of platform economy, which is an emerging issue in the academic literature on policymaking; second, to generate new knowledge interchange dynamics with reference to Barcelona regarding socio-economic challenges; and, third, to develop co-created policy recommendations based on PAR approaches that could have a positive impact on the city from different perspectives (sustainability, work rights, data ownership, etc.). For this, a series of mechanisms and channels of co-creation were established based on diverse approaches, such as the digital commons (Senabre Hidalgo and Fuster Morell 2019), open design (Boisseau et al. 2018), and a temporary policy design lab.

In the first participatory design phase, a strategic analysis was carried out among a small group of 12 representatives (from civil society, digital entrepreneurship, politics, and academia) from the platform economy and social and solidarity economy. The aim was to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the platform economy in the Barcelona context, following SWOT analysis methodology (Martin and Hanington 2012). In the second phase, members of the initial work group and additional participants drafted an online document with possible approaches for new policies. This collaborative text collected draft proposals and specific policy measures to guide the platform economy promotion activities of Barcelona City Council. In the third phase, a face-to-face co-creative session adopted a theory of change model (Martin and Hanington 2012), in order to generate concrete proposals for long-term change, and the steps needed to achieve them. A key priority in this phase of participatory generation of policies was to establish a thematic clustering of proposals with a card sorting technique, used in the fields of knowledge management and user experience design.

In the fourth phase, the project expanded the collaboration process by holding a celebratory Procomuns community event on the platform economy. It was conceived as a co-creation meeting beyond the conference format, including local associations, relevant city actors, international experts, political leaders, and citizens. Collaborative working sessions covered themes, including general regulatory measures, technological developments, tourism, mobility, housing, social inclusion, health and care, and job conditions.

In the final phase, the list of public policy proposals was uploaded, discussed, and voted on online, coinciding with the broader public consultation process to define Barcelona’s Municipal Action Plan (PAM) via the Decidim online platform (Aragon et al. 2017). This gave additional visibility to Procomuns outputs via social networks and importantly provided refinement and social filtering of co-creative results, generating additional public engagement.

Case Study 4: The Duchenne Project – When a CSO Leads the Research Process

An example of CSOs and community-based forms of collaboration is a technology development project that focused on orthoses, more specifically on the correction of limb disorders to support the movement of the upper limbs of children with Duchenne. Duchenne is a type of muscular dystrophy which only affects boys and significantly reduces life expectancy.

The project was driven by the French National Association of Parents of Duchenne Sufferers. The CSO collected funds to set up a foundation to prepare proposals to undertake research that would help patients to regain some movement of their upper limbs. Upon successful creation of the foundation, the CSO managed to attract further co-funding from other related CSO. It then managed to work with relevant scientists to produce a proposal for a national funding call. The CSO was the driving force behind the project, assembling the key actors, notably a leading scientist who served as the guarantor of the scientific quality of the project. The social interaction within the project went far beyond this, however, enabling formal interactions at the project review stage and, arguably more importantly, frequent informal interactions in the form of meetings, telephone conversations, and so on.

The project design was clearly aligned with the aim of producing practical outcomes in the form of technologies that could be used by patients. This vision of the project as highly practice oriented was clearly communicated to all partners. This was accepted and reflected by everybody interviewed for the case study. The choice of participants was driven by this practice-oriented ethos, as well as agreed with the researchers. The CSO not only initiated the project but had a pervasive influence on its development and culture.

As an indicator of the CSO’s impact in terms of knowledge production, it is important to underline that the research agenda was identified and informed by the CSO’s local knowledge. There is an enormous amount of research that has been undertaken to alleviate the suffering of Duchenne patients. The vast majority of this research focuses on the medical condition itself and aims to develop drugs that extend the lifespan and improve the quality of life of patients. The CSO, as an association intimately involved in the day-to-day lives of patients, identified the fact that for the Duchenne sufferers themselves, the loss of movement of their arms can be perceived as worse than their reduced life expectancy.

One notable aspect of this project was the CSO’s prior engagement in research and its experience of being able to influence research that was better targeted to the interests of Duchenne patients. The CSO had been involved in pharmaceutical research for Duchenne patients which, at the time of the project’s launch, had resulted in a clinical study that had attracted several hundred million euros in research funding. This success arguably provided the CSO with the confidence to engage in the next step and drive through a research agenda collaboratively defined for the benefit of the patients.

The main advantage of a participatory approach was that the process of doing research together not only produced a co-created result that was widely shared and implemented. It improved the living conditions of patients and created new knowledge for medical support.

Core Principles and Practices

While the four case studies differ in their conceptual frameworks, areas of application, and disciplinary fields, there are several common aspects that point to key characteristics that are important to consider when planning, facilitating, and accompanying participatory citizen science projects.

Co-define and Address Real-World Problems

A key consideration in all citizen science and participatory research projects that aspire to integrate citizens and other representatives of civil society into their development is the importance of addressing real-world problems and issues (Phillips et al. 2019). It is also necessary to establish mechanisms for co-defining these problems and issues from the outset (Senabre Hidalgo et al. 2018). This can be through the generation, review, and discussion of specific research questions (e.g. STEM4youth and its participatory design approach) or through using PAR principles to undertake a cultural translation process (e.g. science shops, involving students and makers in sustainability issues). Iterative validation mechanisms for the results of each phase (e.g. Procomuns generating and voting on public policy proposals) and how the research agenda itself can be identified and promoted by the local knowledge of a CSO (e.g. the Duchenne dystrophy study) are also key strategies.

The methodological approach should focus on addressing real-world problems which, regardless of its potential academic impact (on journal papers, scientific conferences, etc.), are broadly shared by the participants. This approach is not yet widely used in citizen science projects, but it is clearly reflected in our four case studies that address social issues. In the science shops and citizen social science examples, their approaches have in common the idea that research and action must be done with people and not on or for people. They aim to solve concerns and problems via a hands-on approach, combining scientific knowledge, and in different societal spheres (the economy, environment, science, culture, etc.). Many citizen science projects are designed to address scientific questions or align to specific educational objectives. Co-created citizen science projects that address real-world problems have great potential to impact public understanding (Pandya 2012).

Another key consideration regarding the early stages of participatory problem identification is how co-creation and participatory research can often point to ‘wicked’, ‘systemic’, or ‘multifaceted’ problems. In this sense, every involved actor (from a wide spectrum of ‘amateur’ to ‘professional’ scientists) carries with them their own creative potential and prejudices. Each actor represents a valid expert but also a layperson in relation to the wider field of knowledge. Rather than avoiding the conceptual and theoretical complexities resulting from diversity, co-creation techniques enable a common arena where everyone contributes based on their own expertise. This facilitates the use of a variety of perspectives on real-world problems. Even if only a limited number of real-world problems can be addressed during a citizen science research process, the mere formulation and collection of additional ones can always inform further research and additional action-oriented interventions.

Shared Language and Visual Thinking

When integrating the collaboration of researchers from other disciplines, especially nonacademic participants and communities of interest, it is important to start with facilitation strategies that integrate simple and affordable ways to communicate concepts which are often complex or specific to the scientific world (Richter et al. 2019). A progressive approach and familiarisation between participants based on a shared language, rather than conceptual theories or sophisticated academic discourses, can help to discuss the problems, methods, and solutions to be addressed from a citizen perspective (Mattor et al. 2014). Reflexivity and visual and systems thinking contribute to a methodological starting point that helps channel the perspectives of multiple stakeholders, in order to establish the alignment of interests and participation roles in open science (Ravetz and Ravetz 2017). This approach usually employs diagrams, icons, storytelling, and other techniques derived from participatory design (Sanders and Stappers 2014).

Among the possible methodologies, co-creation techniques and materials are a good starting point (Senabre Hidalgo et al. 2018), where some authors highlight the value of participatory design and its potential to ‘allow more transparent, accountable, and democratic modes of knowledge production, learning and governance’ (Qaurooni et al. 2016, p. 1825). This requires a visual design approach to address wicked problems (climate change, poverty, pollution, etc.), using diagrams, canvases, and gamification techniques to channel citizens’ social concerns and needs into the research process. While acknowledging the power imbalances and continuous negotiations inherent in any collaborative setting, visual materials and facilitation mechanisms in co-created research designs can provide opportunities for people lacking a voice to use science to reveal otherwise hidden or contentious societal problems (like in the case of the Barcelona Public Libraries Network).

The science shop experience also highlights the importance of this aspect, especially the need to invest time to enable the recognition of explicit values and interests of partners that emerge during the initial phases of a project. It is necessary, while translating the problem into a research question, to leave as much information as possible in a shared physical space (permanent or temporary) and capture results of discussions, even on flipcharts, printed posters, or sticky notes. This can visually represent the flow of the project during the research process (Senabre Hidalgo and Fuster Morell 2019), as interests can diverge. A key consideration is that a diversity of actors must find a way to translate their different values and perspectives into a common research goal (e.g. librarians and users of libraries; municipality policymakers and CSOs; and education settings with professional researchers). If the same research questions and their accessible translation in a shared or visual language uses physical artefacts (or online collaboration tools), participants can have continued discussions and iterations regarding new questions, even when they share the same preliminary outputs.

Building the Research Community: Frameworks, Ethics, and Collaborative Decision-Making

These participatory methodologies should consider the importance of discussion and decision-making mechanisms, in order to enable the research process to achieve cooperative governance. For instance, are all partners equal? How do researchers change their usual routines to integrate other stakeholders’ agendas and habits? Furthermore, how can the research team be reflexive? Is it useful to be able to take a step back and evaluate how each other’s expectations are reached? This usually implies trust; otherwise it can be difficult to tackle problems and issues. Talking about implicit expectations leads to questioning one’s values and ethics. Writing down common rules about governance and knowledge sharing can be a first step. Collective decision-making processes usually face the question of how do I understand my counterpart? This is fundamental in all the case studies presented. Participation issues can emerge because participants (laypersons, as well as academics) believe they already know how problem-solving works and how a given problem ‘has to be solved’. Therefore, the challenge in these approaches is to allow mechanisms for each actor to understand their interlocutor and for the project’s early development to actively create the space for a decision-making process (where some uncertainty can help to challenge the respective levels of individual routines and self-assurance).

In the experiences reflected here, and the further studies and literature we refer to, several simple coordination mechanisms can be adopted to draw out conflict and agreement – from simple brainstorming techniques, such as using sticky notes to summarise early concerns, to varied research methods or tools (which can be voted on with coloured dots or other mechanisms), to ad hoc agreements in small groups between researchers and citizens when doing collective data interpretation of preliminary outputs. This was demonstrated in the Neighbourhood Water and Duchene projects. Small groups can help to establish a common vision among coresearchers on what to do with the project results (publication, actions, productions, media releases, etc.). In the Neighbourhood Water project, for example, it was decided to produce a poster for a window in a crowded street of the neighbourhood public library. And in the Duchene project, patients gained improved quality of life. In another citizen science case study on mental health, a dissemination-oriented report was produced and shared widely to reinforce the importance of caregivers in mental healthcare provision.

The Role of Mediation and Participatory Meetings

When activating participatory processes in research, another key factor is including a diversity of voices and perspectives. As pointed out by the literature on co-creative PAR and CSO-related approaches to research activity, it is essential that someone is responsible for carrying out a well-planned, independent, and neutral facilitation during group sessions. Whether or not they have a complete understanding of the research topic or questions, a facilitator can create the necessary conditions for equitable and free speaking. They can also support collective decision-making mechanisms during intense participant meetings, ideally in face-to-face interactions.

A facilitator is in charge of suggesting the materials and dynamics in advance and discussing it with participants. They need to have a script for the co-creative sequence that is going to take place. During each session, a facilitator explains what is going to be done, clarifies doubts, and controls the time needed for each co-creation phase. The facilitation role can also be a turning role, or even be delegated to a small number of people who are outside the research group. This role needs to be flexible, considering how the group moves forwards in the different research phases by facilitating agreement and adapting development strategies. Facilitation, understood as one of the main activities of intermediation (e.g. in science shops), requires intensity and effort, agility and reflexivity, as well as some moderation experience and personal empathy. For these reasons, if the role is performed by two facilitators or even a small group, it can improve the efficiency and quality of the outcomes.

This also relates to the importance of space and infrastructure for face-to-face collaboration. This is reflected in the science shop practices, the temporary policy design lab concept from Procomuns events, the community hubs in the citizen social science libraries, and how the CSO leading the Duchene project operated outside of the usual medical settings. The way rooms are furnished, or what kind of spaces are available as meeting points (sometimes having a symbolic value), can ease or hinder the practice of facilitation. For instance, meeting in the town hall might prevent some participants from attending (depending on citizens’ sociocultural backgrounds or political orientations, etc.). Participatory design thinking usually includes a view on the meeting rooms and materials to be provided in order to align with the meeting’s objectives and participants. In contrast to the restricted conditions of laboratories in universities and research institutes, considering infrastructure and facilitation can become crucial to achieving flexibility and transparency when orienting research in a participatory and inclusive way.

Participation Tools and Channels

A series of common considerations on the tools and channels used for wider and more efficient participation are closely related to the focus on real-world problem-solving, a shared visual language, decision-taking mechanisms, and the importance of facilitation and physical infrastructure for face-to-face interactions. Similar to the approach described in the Procomuns and citizen social science case studies (integrating the participation of different stakeholders through a long iterative process), co-creative participatory research also requires adequate communication and interaction channels, from project coordination to progressive validation of results (Sanders and Stappers 2014). When defining an incremental process of idea generation, discussion, and selection of proposals in a participatory manner, the approaches described here provide valuable elements to consider. One of them is the importance of combining physical or analogic materials (visual canvases, collage diagrams, posters about results, etc.) with online mechanisms and tools, such as in collaborative writing applications and democratic participation platforms (Aragon et al. 2017).

This combination should facilitate the sequencing process from robust proposals, generated in face-to-face participatory design dynamics, to the online integration of diversity with as many points of view as possible. When systematising results, the mechanisms for guiding analyses should be open, reliable, and verifiable. The three main components of participatory science (Kimura and Kinchy 2016) are (1) production of knowledge from empirical data, (2) commitment to an objective of decision-making for the action, and (3) cooperation with civil society actors stemming and other stakeholders. These point to the constant need to consider, adopt, and adapt new tools and research design channels that allow collective decision-making and shared access to outputs. The emergence and ‘natural selection’ of ICT for communication and collaboration represents an opportunity to select the appropriate ones for project facilitation. However, different criteria should be considered with regard to ICT and digital channels, such as ease of use and acceptance levels of tools (especially if participants have low levels of digital literacy). To what extent tools serve the intended aim of accessibility and openness should also be evaluated.

Projects can provide ICT training and also produce online and physical boundary objects, such as toolkits, guidelines, manuals, etc. (Star and Griesemer 1989), to make co-creation strategies and interactions more effective and scalable. The objectives of a given co-creative approach and the roles of the involved actors should be viewed as co-shaped with other actors and institutions over time. For example, the 3-day training sessions with librarians as citizen science facilitators were proposed during the project for the participants in order to discuss and learn how to work collectively. This proved to be complex, as it threatened librarians’ social status and professional identity. This type of training on co-creative methods and tools can also provide opportunities to review research designs and to develop new research avenues.

Discussion

Co-creative processes and experiences in PAR, CSOs, citizen social science, and science shops need to be considered to enhance active, inclusive, and wide participation in citizen science projects. The concerns of citizens, as coresearchers, should be placed at the centre of the research cycle, as argued in this chapter. This way coresearchers can engage in all stages of the research cycle. However, when articulating co-creation methodologies in citizen science projects, a number of challenges emerge.

A focus on real-world problems requires balancing social and scientific interests and impacts. Research design and question formulation need to be guided by the different levels of knowledge and techniques of negotiation among the participants. This was evident in the negotiations of the CSO and researchers for the benefits of patients in the Duchenne case study and in the Procomuns process for generating public policy recommendations via a bottom-up approach. In the context of citizen science, collective data interpretation and evidence-based analysis of social change impacts are less common and studied in comparison to the initial stages of research (Shirk et al. 2012). In our opinion, this reflects the need to explore and analyse more case studies, especially successful examples reflected in both robust academic references and practices from participatory research studies in the social sciences (Heiss and Matthes 2017). Also reflecting the value of wider participatory approaches in citizen science is the fact that, due to the increased complexity of real-world problems and societal challenges, no meaningful solutions can be achieved without inclusive co-creation approaches and reflexive decision-making processes. It is also important to consider that sometimes citizen science approaches can be abused or misused by drawing citizens into projects with hidden agendas.

Another important challenge identified is the need to further develop and adopt facilitation roles, especially in an independent manner. Ethics and reflexivity can combine peer-to-peer and internal evaluation criteria to build up a collaborative governance of projects (Böschen et al. 2020). Accessible visualisation tools can provide a better understanding of participatory research processes and outputs in terms of scientific data, as well as open online platforms for public deliberation on the interpretation of scientific results. Reaching consensus from citizens and CSOs regarding derived actions and policies can also benefit from such designs (Aragon et al. 2017). Digital tools can bring additional layers and complexities to the face-to-face co-creation process when supporting future citizen science practices. In our opinion they represent another key factor to improve and ‘close the loop’ of co-creative work on real-world problems in relation to the type of practices described here.

In considering how co-creation and participation can articulate the basis for new citizen projects, the role of the facilitator is key. However, this requires a specific type of personal attitude, background, and know-how which cannot be easily defined and taught. From our perspective, based, for example, on the experience of science shops, facilitation usually requires more than communicative and dialogical translation work, since the knowledge and expertise from such intermediaries can influence in many ways the effectiveness of a participatory approach. For this, one possible way to consider the necessary training and scale of facilitation roles for citizen science is to combine practical and theory-based knowledge for specific types of research facilitators. This means activating and improving facilitation by learning first-hand about specific how-to guides like the ones mentioned here (such as design thinking, collaborative project management, and other learn by doing approaches), in combination with existing methodologies and practices from the social sciences (especially in relation to social movements, organisational learning, and PAR). This way, intermediaries and facilitators can pinpoint methodological mistakes, misunderstandings, and even abuse.

Finally, some of the key principles and values regarding shared decision-making, governance, and openness, reflected here, point to how the articulation of communication and open research outcomes can provide the basis for the necessary levels of trust among all the involved actors. In this regard, the key elements of collaborative work and regular communication with participants, articulating comprehensible timeframes and rules for participation, as well as digital channels to discuss issues around policies at any given moment, can be seen as a starting point for even more ambitious ways of doing science in the future.

Further Reading

International Science Shop Network. (n.d.). Living knowledge toolbox. https://www.livingknowledge.org/resources/toolbox/. Accessed 10 June 2020.

STEM4youth. (n.d.). Citizen Science toolkit. https://olcms.stem4youth.pl/content_item/detail/223. Accessed 10 June 2020.

References

Aragon, P., Kaltenbrunner, A., Calleja-López, A., Pereira, A., Monterde, A., Barandiaran, X. E., & Gómez, V. (2017, September). Deliberative platform design: The case study of the online discussions in Decidim Barcelona. In International conference on social informatics (pp. 277–287). Cham: Springer.

Becker, F., & Zacharias-Langhans, K. (2014). Hands on! – Mutual learning in co-operation of civil society and scientific community. In S. Brodersen, J. Dorland, & M. Jorgensen (Eds.), Paper book: Living knowledge conference (pp. 31–45). Copenhagen: Aalborg University.

Becker, F., Beyer, E., Buxhoeveden, J., Dietrich, J., Krüger, F., & Prystav, G. (2018). Forschendes Lernen in selbst organisierten Projektwerkstätten. In J. Lehmann & H. Mieg (Eds.), For-schendes Lernen, Ein Praxisbuch (pp. 187–199). Potsdam: Verlag der FH.

Boisseau, É., Omhover, J. F., & Bouchard, C. (2018). Open-design: A state of the art review. Design Science, 4, e3. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2017.25.

Bonhoure, I., Cigarini, A., Vicens, J., & Perelló, J. (2019). Citizen social science in practice: A critical analysis of a mental health community-based project [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/63aj7.

Böschen, S. Legris, M. Pfersdorf, S., & Carsten Stahl, B. (2020): Identity politics: Participatory research and its challenges related to social and epistemic control. Social Epistemology [Online preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1706121.

Cigarini, A., Vicens, J., Duch, J., Sánchez, A., & Perelló, J. (2018). Quantitative account of social interactions in a mental health care ecosystem: Cooperation, trust and collective action. Scientific Reports, 8, 3794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21900-1.

Cigarini, A., Vicens, J., & Perelló, J. (2020). Gender-based pairings influence cooperative expectations and behaviours. Scientific Reports, 10, 1041. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57749-6.

Escobar, O. (2014). Upstream public engagement, downstream policy-making? The brain imaging dialogue as a community of inquiry. Science and Public Policy, 41(4), 480–492.

Frick, V., Jaeger-Erben, M., & Hipp, T. (2020). The ‘making’ of product lifetime: The role of consumer practices and perceptions for longevity. In N. F. Nissen & M. Jaeger-Erben (Eds.), PLATE: Product lifetimes and the environment 2019. Berlin: TU Berlin University Press.

Heiss, R., & Matthes, J. (2017). Citizen science in the social sciences: A call for more evidence. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 26(1), 22–26.

Hickey, G., Richards, T., & Sheehy, J. (2018). Co-production from proposal to paper. Nature, 562, 29–31.

Irwin, A. (2002). Citizen science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. London: Routledge.

Keiller, S., & Charter, M. (2016). The second global survey of repair cafés: A summary of findings. Farnham: The Centre for Sustainable Design. http://cfsd.org.uk/research/.

Kimura, A. H., & Kinchy, A. (2016). Citizen science: Probing the virtues and contexts of participatory research. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 2, 331–361.

Kullenberg, C., & Kasperowski, D. (2016). What is citizen science? – A scientometric meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(1), e0147152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147152.

Kythreotis, A. P., Mantyka-Pringle, C., Mercer, T. G., Whitmarsh, L. E., Corner, A., Paavola, J., et al. (2019). Citizen social science for more integrative and effective climate action: A science-policy perspective. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00010.

Martin, B., & Hanington, B. M. (2012). Universal methods of design: 100 ways to research complex problems. Develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. Beverley: Rockport.

Mattor, K., Betsill, M., Huber-Stearns, H., Jedd, T., Sternlieb, F., Bixler, P., et al. (2014). Transdisciplinary research on environmental governance: A view from the inside. Environmental Science & Policy, 42, 90–100.

Nowotny, H. (2003). Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Science and Public Policy, 30(3), 151–156.

Pandya, R. E. (2012). A framework for engaging diverse communities in citizen science in the US. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(6), 314–317.

Perelló, J., Murray-Rust, D., Nowak, A., & Bishop, S. R. (2012). Linking science and arts: Intimate science, shared spaces and living experiments. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 214(1), 597–634.

Phillips, T. B., Ballard, H. L., Lewenstein, B. V., & Bonney, R. (2019). Engagement in science through citizen science: Moving beyond data collection. Science Education, 103(3), 665–690.

Qaurooni, D., Ghazinejad, A., Kouper, I., & Ekbia, H. (2016, May). Citizens for science and science for citizens: The view from participatory design. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1822–1826). New York: ACM.

Rabeharisoa, V., & Callon, M. (2004). Patients and scientists in French muscular dystrophy research. In S. Jasanoff (Ed.), States of knowledge. The co-production of science and social order (pp. 142–160). London: Routledge.

Ravetz, J., & Ravetz, A. (2017). Seeing the wood for the trees: Social Science 3.0 and the role of visual thinking. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 30(1), 104–120.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage.

Richter, A., Sieber, A., Siebert, J., Miczajka-Rußmann, V., Zabel, J., Ziegler, D., et al. (2019). Storytelling for narrative approaches in citizen science: Towards a generalized model. Journal of Science Communication, 18(6), A02.

Rogers, R. (2013). Digital methods. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: Three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign, 10(1), 5–14.

Scheumann, R., & Becker, F. (2014, April). Benefit of re-use of IT hardware for society and environment – A German business case. In Paper book: Living knowledge conference (pp. 293–303). Copenhagen.

Senabre Hidalgo, E., & Fuster Morell, M. (2019). Co-designed strategic planning and agile project management in academia: Case study of an action research group. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0364-0.

Senabre Hidalgo, E., Ferran-Ferrer, N., & Perelló, J. (2018). Participatory design of citizen science experiments. Comunicar, 26(54), 29–38.

Shirk, J., Ballard, H., Wilderman, C., Phillips, T., Wiggins, A., Jordan, R., et al. (2012). Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecology and Society, 17(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04705-170229.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, translations and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420.

Vicens, J., Bueno-Guerra, N., Gutiérrez-Roig, M., Gracia-Lázaro, C., Gómez-Gardeñes, J., Perelló, J., et al. (2018). Resource heterogeneity leads to unjust effort distribution in climate change mitigation. PLoS One, 13(10), e0204369. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204369.

West, J., & Bogers, M. (2017). Open innovation: Current status and research opportunities. Innovations, 19(1), 43–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Senabre Hidalgo, E., Perelló, J., Becker, F., Bonhoure, I., Legris, M., Cigarini, A. (2021). Participation and Co-creation in Citizen Science. In: Vohland, K., et al. The Science of Citizen Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-58277-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-58278-4

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)