Abstract

In this chapter, the educational gradient in access to different organizational work-family policies is examined using unique multilevel survey data from the European Sustainable Workforce Survey covering nine European countries. A total of six different work-family policies are studied, representing working-time arrangements, leaves, and services. By combining information provided by the organization, the direct supervisor, and the employee we show that for all policies, access reported by employees is substantially lower than provision reported by the team managers, which in turn is lower than the provision reported by the HR managers. This points to complex processes in the distribution of information in organizations. Moreover, at the organizational as well as the employee level, higher skilled employees have more access to working-time arrangements. We conclude that the skill gaps in the access to organizational work-family policies identified in this chapter form an important dimension of social inequality in today’s labor market.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This chapter further explores organizational work-family policies, following up on the literature review in Chapter 21 by Chung in this volume. The entrance of women and in particular mothers into the labor force across industrialized countries in the past decades has prompted governments and employers to accommodate the family demands of their workforce by implementing policies such as flexible working times and parental leaves. Not only for female employees but also for men who no longer rely on a homemaker spouse for care tasks, increasingly face work–life balance challenges. In many organizations, work-family policies are part of competitive employee benefits and serve as a way to attract sought-after employees. Indeed, previous research has shown that highly skilled and/or highly paid workers are more likely to have access to and use work-life policies (Chung, 2018; Golden, 2008; Weeden, 2005). Moreover, while women perform the majority of caring and household tasks, they are not more likely to have discretion over their work hours, nor are employees with small children (Golden, 2001; Ortega, 2009). This suggests that work-family policies, rather than being used for the benefit of the part of the workforce that has the strongest need for support in reconciling work and private life, for instance, low-income families or single parents, these policies are offered to high-status workers who possess skills valuable to their employers. This relates to issues of social inequality: in most industrialized countries diverging trends between the higher and lower educated in terms of income have occurred since the 1980s. But in addition, social inequalities in terms of life chances more broadly such as health (Präg & Subramanian, 2017), family relationships (McLanahan, 2009), and life satisfaction (Gerdtham & Johannesson, 2001) are on the rise. An important potential source of such disparities which we focus on in this chapter is the access to organizational work-family policies among different groups of workers.

In this chapter, we examine the access to organizational work-family policy, that is whether managers and employees report that a certain policy exists in their organization. We use the terms availability, access, and provision interchangeably. When referring to the educational gradient we also refer to skills or the skill gap. We aim to answer the following research questions: (1) Are organizations with a higher proportion of highly skilled employees more likely to provide access to organizational work-family policies? (2) Are higher skilled employees more likely to report access to organizational work-family policies? (3) How is the combined provision of work-family policy at organizational and team level related to employee’s perceived access to the policy and does this differ by employee skills?

We use unique multilevel survey data from the European Sustainable Workforce Survey (ESWS from here on, Van der Lippe, Lippényi, Lössbroek, et al., 2016) to investigate the educational gradient in the organizational provision of a variety of work-family policies at different organizational levels. Specifically, our contribution to the knowledge on access to work-family policies is threefold: first, we assess the availability of a variety of work-family policies at three different levels, enabling us to examine the consistency between policy provision at the organizational (highest) level as compared to the department manager (middle level) and how this relates to employees’ perceived access to work-family support (lowest level). We thereby shed more light on how policies are distributed to various groups of workers within organizations. Exploring how employee’s perception of availability relates to organizational provision measured independently also illustrates potential difficulties in validly and reliably assessing availability of work-family policies in employee surveys. Secondly, we model the educational gradient in access to the different work-family policies considered while controlling for the main theoretical explanations at employee and organizational level why higher skilled workers would be expected to have more access to these policies. We argue that this “net educational gap” in the availability of work-family policies reflects an important dimension of social inequality. Thirdly, our multi-outcome, multilevel design encompasses nine European countries, thereby increasing the scope of previous studies.

Background and Expectations

In this chapter, we examine work-family policies provided by organizations. We define these as policies aimed to facilitate employees in combining paid work and family responsibilities which go above and beyond statutory arrangements mandated by national law.Footnote 1 The types of policies considered in this chapter follow the conceptualization of organizational work-family policies provided in Chapter 21 by Chung (in this volume) which distinguished three categories. These represent the full range of work-family policies commonly provided by employers to facilitate the combination of work and (family) life (Been, 2015; Plantenga & Remery, 2005) and are (1) working-time arrangements, (2) leaves, and (3) services. As noted by Chung (this volume) there are not many cross-national data sources that provide information on all categories of organizational work-family policies as most surveys focus on flexibility arrangements. Exploiting the richness of the ESWS (Van der Lippe, Lippényi, Lössbroek, et al., 2016) we are able to include in our analysis six different organizational work-family policies covering all three types. These are working from home, flexible start and finish times, and a reduction in work hours (working-time arrangements), supplemental family leave and the extension of statutory leave with vacation days (leave), and childcare assistance in the form of company-based childcare, financial assistance, or mediation in finding a spot (services).

We develop expectations about differences in access to organizational work-family policies by employee’s skill level and distinguish between policy provision reported at the organizational level by the human resource manager (thus relating to differences between organizations) and perceived availability reported by employees within organizations. For each of the six organizational work-family policies considered, we ask whether an organization with a higher proportion of highly skilled employees is more likely to provide this policy and whether at the employee level the higher skilled employees are more likely to have access to the policy. Moreover, we exploit the fact that provision of work-family policies was reported in our data at the organizational and team level, enabling us to combine these sources of information to present a more fine-grained examination of the combined availability of work-family policy for different groups of workers.

Drawing on the main theoretical mechanisms for why work-family policies are adopted by organizations and for which groups of employees within organizations, as described in Chapter 21 by Chung (this volume), we develop expectations about whether an educational gradient in access to the different policies exists between and within organizations (see Table 22.1 for an overview).

While decreasing work-family conflict may be the primary aim of work-family policies, the degree to which these measures also serve the interest of employers—for instance, by directly increasing workers’ productivity or by enhancing worker commitment and retention—varies, and so do the costs associated with offering these policies. This implies that certain groups of workers which are perceived by employers as more valuable to the organization and/or more likely to show increases in productivity when supported by work-family policies are expected to be more likely to have access to them (Lambert & Haley‐Lock, 2004). This argument has been put forward in particular with regard to flexibility policies (Chung, this volume). These policies not only help employees to achieve better work–life balance but can also enhance worker productivity by enabling workers to carry out their work more flexibly. Workers with a high degree of autonomy in carrying out their tasks likely gain most in terms of productivity. As this applies primarily to higher skilled white-collar jobs, we expect that an educational gradient exists in the access to flexibility in time and location of work. Following this argument, a higher proportion of highly skilled workers in the organization should also be associated with a higher likelihood of the organization offering these policies. Thus, organizations with a higher proportion of workers in high-skilled positions will be more likely to report that they provide flexibility policies.

With regard to supplemental leave (i.e., family leave offered by the organization which is longer in duration or with a higher income replacement than the statutory national allotment) and childcare assistance, the implications for enhanced performance are less clear-cut. Yet, these policies can be a powerful means of signaling organizational concern for employee’s well-being, resulting in increased commitment, performance, and retention on part of the employee (Begall et al., 2020; Kurtessis et al., 2017). The assumed mechanism is that perceived organizational support elicits the norm of reciprocity, leading to a perceived obligation to help the organization and increased feelings loyalty and commitment (Gouldner, 1960; Wheatley, 2017). Because supplemental leave and childcare assistance are relatively costly policies to implement, we expect that employers would adopt these for the parts of their workforce most valuable to the organization in order to invest in their loyalty and commitment. On the other hand, since the use of these policies is less dependent on job characteristics (contrary to flexibility), concerns about social legitimacy may inhibit employers from offering these policies only to selected groups of workers whom they wish to retain. These arguments lead us to expect no educational gradient in access to these policies within organizations. It is important to note that certain categories of employees may nevertheless be formally excluded from using the policy, for instance, those with temporary contracts (Chung, 2018). Because supplemental leave and childcare assistance are costly programs and employers are more likely to employ these strategies to attract and retain workers with highly valued or scarce skills, we expect that organizations with a higher proportion of workers in highly skilled positions will be more likely to report that they provide supplemental leave and childcare assistance.

The remaining two work-family policies we consider—offering a reduction in work hours and using vacation days to extend family leave—can from the employers’ perspective be regarded as low-cost options without performance implications and thus can be expected to be made available for everybody to the same extent. As such, they form an interesting point of reference in our comparison. This means that for these measures we expect the lowest degree of within-organization stratification according to education. The same argument can be applied to between-organization differences, where we expect that the provision of these policies is not predicted by the proportion of workers in higher skilled positions.

Combined Availability of Work-Family Policies

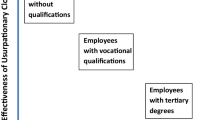

Within organizations, policies are filtered by different levels of hierarchy before reaching individual employees. This can occur in the form of formal regulations as certain jobs may not be suitable for the use of certain policies, but this process may also occur informally. Lower-level management can grant access to work-family reconciliation measures not formally adopted by the organization, for instance, through granting workers flexibility in working times informally by allowing teams to plan their own work-rosters (Been, 2015; Lambert & Haley‐Lock, 2004). Similarly, lower-level managers may constrain the access to policies by not communicating the existence of the policy to their employees or by informally obstructing the use, as has been frequently reported for men’s use of parental leave (Allard, Haas, & Hwang, 2011). Figure 22.1 summarizes the four categories in the combined availability of work-family policies in case of two hierarchical levels. While our survey data on availability of work-family policies does not entail information about the reason or intention for (not) making a policy available at either level, the labels are useful for structuring our thinking about inconsistencies in reports from different sources. Because the multitude of potential mechanisms to be considered across the four categories and six organizational work-family policies considered here we do not formulate explicit expectations, but test for each policy whether the educational gradient in employees’ reported access differs across the combined availability at organizational and team level.

Alternative Explanations

A number of alternative explanations at individual and organizational level which may fully or partially account for any educational gradient in access to organizational work-family are included in the empirical test of our expectations. At the individual level the most important predictors of access to work-family policies identified in the literature (see also Chapter 21 by Chung in this volume) are the autonomy in tasks (specifically for flexibility), characteristics of the workers related to relative bargaining power such as tenure, permanent position, occupational status, and work hours, and the actual need for work-family support indicated by workers’ sex and the presence of young children in the household.

Alternative explanations for why organizations provide work-family policies relate to pressures of social legitimacy, to which larger and public sector organizations are more susceptible, and internal demand indicated by a higher proportion of women. Since not all types of work are suitable to implement flexibility policies and to account for sectoral agreements which might exist in some countries, we include information about the industry. Moreover, we take into account that work-family policies may serve as a way to attract sought-after staff by including information about whether organizations reported difficulties finding skilled employees. Because flexibility may be part of a high-performance strategy, we include information about the proportion of employees with performance-based pay.

Extending our perspective from between-organization to between-country differences, organizational polices can either extend or supplement national policies or act as a substitute in the case of a lack of national provisions. Institutional theory maintains that organizations’ provision of work-family policies is a response to normative pressures from the environment (Beham, Drobnič, & Präg, 2014). Previous findings support this notion as it has been found that national provisions of leave, childcare, and work-hour flexibility correlate positively with organizational provisions of these measures (Den Dulk, Groeneveld, Ollier-Malaterre, & Valcour, 2013). In order to account for the large variation in institutional contexts represented in the nine countries in our study (Begall & Van Doorne-Huiskes, 2019), we include country dummies in all models.

Data

We make use of the ESWS (Van der Lippe, Lippényi, Van Lössbroek, et al., 2016), which contains data on 10,673 employees, 726 departments or teams, and 259 organizations in Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK, collected in 2015/2016. Organizations were sampled based on their representation of six different sectors (manufacturing, health care, higher education, transportation, financial services, and telecommunication) and three different sizes (1–99 employees; 100–249; 250 or bigger), using a combination of stratified random sampling and personal connections. After organizations agreed to participate, employees and department managers were addressed at work and asked to participate in an online or paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The human resource manager filled in the questionnaire on behalf of the organization, as is common in this type of research because they are considered to be well-informed about the entire organization (Haas & Hwang, 2016). The response rate was 61.4% among employees, 80.9% among team or department managers, and 98% among the organizations that had agreed to participate.

Motivation and Challenges Collecting the European Sustainable Workforce Survey

We encountered numerous challenges during the collection of data. The first challenge was the choice of countries and sectors. The nine countries constitute different types of welfare regimes (Bäck-Wiklund et al., 2011). Although differences between these types are somewhat fluid, Finland and Sweden are typically categorized as social-democratic regimes, Germany and the Netherlands as conservative regimes, Spain and Portugal as Mediterranean regimes, the UK as a liberal regime, and Hungary and Bulgaria as post-communist regimes. The six industries are selected to reflect variation in the causes and types of investments in a sustainable workforce. These six industries vary therefore in the percentage of women working in the sector, the percentage of older employees, flexibility in contracting, and the extent of technological development.

The second challenge was that the unique depth of the ESWS limited the possibilities of drawing a random representative sample from the whole population of organizations. Instead, we used stratified purposeful sampling. First, we used quantitative sampling to randomly select cases within sector and size categories from lists of business organizations. Second, we complemented the random selection with convenience sampling of cases from alternative sources, mainly web searches and referrals. We used this method when the random sample from the business lists did not yield enough participants.

The third challenge was the participation of organizations, as they often conduct their own surveys of employees and see surveys as an extra burden on employees. We targeted the relevant gatekeepers being the HR managers as the actors who are potentially most interested in this research. A team of native research assistants in each country performed a web search and made calls to the establishment to get the contact details of the HR manager. In most cases, we then visited the HR manager to get his or her cooperation. It was thereby important to provide credentials and offer a tangible product in return for cooperation. We offered a benchmark report which compares the establishment with establishments from the same sector and country with regard to workforce investments and key productivity outcomes. Organizations value information about what their competitors are doing and how they perform. In our fieldwork, organizations mentioned seasonal high workload as a vital constraint not to cooperate.

The fourth challenge was participation of employees and managers, albeit this turned out to be a smaller issue than entering the organization. Once an organization joined our research, the response rate was good. In order to minimize individual variation within establishments, we sampled a limited number of employee groups, mostly teams. This also allowed us to survey managers of teams and match them with employees. Managers are an important employee group to study in their own right, and their reports provide extra information about workplace characteristics. A similar strategy, using occupational groups, has also been successfully employed in the Dutch Time Competition Survey (Van der Lippe & Glebbeek, 2003). At least two teams were chosen that represent the organization’s core activity: for example, if the organization is a hospital, we interviewed nurses. Furthermore, we chose at least one team whose tasks do not particularly refer to the core activity of the organization, such as finance, communication, or maintenance departments. The rationale was that support teams perform similar activities regardless of the sector, and this provides an opportunity to compare economic sectors while limiting the variability in job characteristics. We used incentives and offered the choice between a lottery among employees who completed the survey and a monetary gift to the organization to spend on organizing activities for staff. Furthermore, we used other well-established strategies to get cooperation from employees and managers, being a personalized cover letter and invitation email where we had access to names, and where we emphasized anonymity and trustworthiness.

The ESWS is unique among organizational surveys. It has a multilevel design, including a large-scale sample of employees and managers within teams and organizations, and it is also cross-country comparative.

Measures

Organizational and Team Level

Availability of work-family policies was measured at the organizational level (reported by the HR manager) and the team or department level (reported by the team manager). Both respondents could indicate whether their establishment (respectively department) offered employees the possibility to “work at home during normal working hours” and use “flexible starting and finishing times (for example, to start working at 7AM one day and at 9AM another day).” The options “switching to working fewer hours a week” or “taking holiday to extend leave period” were reported separately for male and female employees and asked explicitly in the context of availability and use of leave and childcare arrangements. Both policies were coded as available if they are offered to at least one group (men or women) in the organization (department). Supplemental family leave was coded as available if the organization (department) offered either “a longer period of leave than it is obliged to offer by law” or “better-paid leave arrangements than it is obliged to offer by law” for any of the following categories: Longer maternity or paternity leave or longer parental leave for women and/or men. Again, these items were separately assessed but recoded here as available if at least one of the eight options were available. With regard to childcare assistance, financial assistance, childcare at the workplace, and assistance finding or arranging childcare were reported separately but coded as available in this analysis if at least one of the three types of assistance was available. The questions concerning childcare assistance were only reported by the HR manager (organization level).

The proportion of workers in (highly) skilled positions was reported on both levels by the HR manager on a nine-point scale ranging from none (1) to all (9). Furthermore, we take into account whether according to the HR manager the organization had difficulty finding staff for skilled jobs with answers ranging from 1 (very often) to 5 (never). The HR manager also indicated what proportion of nonmanagerial employees receives wage or salary components that depend on their individual performance on a six-point scale ranging from “none” to “most.”

Additional organizational level controls are the industry and sector (private vs public) in which the organization is active, the natural logarithm of organizational size and the proportion of women among the employees (1 = none to 9 = all). Descriptive statistics of all variables at the employee level are presented in Table 22.2.

Employee Level

From the employee questionnaire we obtain employees’ education (coded in seven categories ranging from 1 = primary education to 7 = Ph.D.), occupational status coded as International Socio-Economic Index of occupational status (ISEI, Ganzeboom, De Graaf, & Treiman, 1992) and monthly earnings which we coded in country-specific deciles. Job autonomy is measured by four items assessing the freedom of the respondent in deciding the tasks and their order as well as when and how to do the work. Factor and reliability analysis (available upon request) confirmed that these items could be collapsed in one scale of job autonomy on a five-point scale with higher values indicating more autonomy. Moreover, we also include weekly work hours, job tenure in years, whether the respondent has a permanent contract, the presence of children under the age of 18 in the household and the age of the youngest child, the presence of a partner in the household, and respondents’ age in years and sex.

Analytical Strategy

To test our expectations presented in Table 22.1 we estimate two series of models, at the organizational level (n = 259) and at the employee level (n = 10,673) level. At the organizational level we predict the availability of each work-family policy by the proportion of workers in highly skilled positions (Model 1), and controlling for industry, sector, country, organizational size, the proportion of female workers, the degree of difficulty in finding skilled staff, and the proportion of employees with performance-based pay (Model 2). We use logistic regression models to predict the availability of policies since they are all measured as dichotomous variables (not available = 0, available = 1). Because of the small sample size models were estimated using a penalized maximum likelihood estimator (Rainey & McKaskey, 2015). These models provide an estimate of the skill gap in access to work-family policies between organizations.

At the employee level we use logistic organization-fixed effects regression models to predict the perceived availability of each work-family policy to estimate the educational gradient within organizations (Model 1), and controlling for all individual-level controls (Model 2).

In the second series of models we predict the perceived availability of each policy at the employee level by the combined availability at organizational and department level (see Fig. 22.1) and education as well as individual and organizational controls. Because employees are clustered in teams within organizations, we estimate three-level random intercept models and include a random slope for education. We estimate two models for each policy, a first model with the combined availability at organizational and departmental level, employee education, occupational status, income, and all other individual and organizational controls (see Table 22.2). In the second model we allow for an interaction between the combined availability and employee education to assess the educational gradient separately for each category.

Results

Before turning to discussing the multivariate results, we present the reported availability of policies at organization, team, and employee levels in Fig. 22.2. The availability of policies varies substantially according to type and the level of reporting. The most common policies offered by organizations are a reduction of work hours and the use of vacation days to extend leave. More than 80% of the organizations in our sample offer these measures. Since most employees have a legal right to accessing both measures and they are cost-free it is not surprising that these are most frequently offered, but since the questionnaire of the ESWS asked about providing these measures specifically in the context of childcare and leave arrangements, we regard them as part of the range of organizational work-family reconciliation measures. Interestingly, employees appear not to be well-informed about the possibility to reduce their work hours, as less than 30% report this as available in their organization. The availability of extending leave with vacation days was not measured at employee level.

Flexibility in the time and location of work is available at the majority of organizations as work-time flexibility is the third most frequently provided measure with 75% of organizations reporting to offer it, and more than half report that their employees can work from home during office hours. It is noteworthy that employees’ perceived availability is substantially lower compared to the report by managers. Only 46% report access to flexible work times and 29% to working from home.

The least frequently provided measures are supplemental leave and childcare assistance, less than one-third of organizations provide these options. These policies are most costly and directly benefit the employee more than the employer. For both policies, the provision at the team level (reported by employees’ direct supervisor for his/her own team) is approximately 10 percentage points lower than at the organizational level. Among employees, just over 10% state that supplemental leave and childcare assistance are available at their company.

Because the sample of the ESWS is not a random sample, it is not clear in how far these numbers can be interpreted as reliable estimates of the availability of work-family policies in these countries and large-scale data sources assessing different work-family policies to which these numbers could be compared to are scarce. The fact that our numbers are consistent with the findings reported in Chapter 21 by Chung (this volume) is reassuring in this regard.

How the two levels come together in the combined availability (see Fig. 22.1) is presented in Fig. 22.3 as the percentage of employees in each category for the different policies. The bars are sorted by “consistent access,” which refers to the situation in which both HR manager and team manager report that access to the policy is provided in their organization. The figure shows that inconsistent categories, which we refer to as restricted and informal access, are relatively most common for working from home and supplemental leave. For both measures, the category of restricted access, i.e., where the policy is reported as available at the organizational but not at the team level, is relatively large compared to the situation of consistent access.

Turning to the multivariate results, Fig. 22.4 and Table 22.3 present the results of the regression model predicting the provision of each policy at the organizational level. The predictor of interest is the proportion of workers in (highly) skilled positions, which we expected to be positively associated with the provision of flexibility policies, supplemental leave, and childcare assistance but not with the possibility to reduce hours or extending leave with vacation days (see Table 22.1). Figure 22.4 shows the exponentiated coefficients (odd’s ratios) associated with a one-unit increase in the proportion of staff in (highly) skilled positions on the likelihood that each policy is provided according to the HR manager. We report a model with only the proportion of (highly) skilled staff (Model 1) and a model which includes all controls at the organizational level (Model 2). The full estimates of all control variables are presented in Table 22.3. The results confirm our expectation with regard to flexibility policies: both measures are more likely to be provided when there are more workers in highly skilled positions (Model 1). The inclusion of the control variables accounts partially for the effect of a higher proportion of highly skilled workers on flexible work times, which is no longer statistically significant in Model 2. For the other four measures no association between more high-skilled positions and the likelihood of provision is found. However, for supplemental leave, the effect of more highly skilled positions falls short of conventional statistical significance only after control variables are introduced and given the low power at this sample size, we might just not be able to detect this effect with sufficient precision. The effects of control variables included to account for alternative explanations of the skill-policy provision relationship mainly pertain to country differences. In addition, larger companies are more likely to provide childcare assistance and compared to organizations in manufacturing, companies in telecommunication are more likely to provide access to working from home.

(Note See Table 22.3 for full model [model 2])

Effect of the proportion of employees in highly skilled position on likelihood of policy provision at organizational level (n = 259), reported by HR manager (odd’s ratios)

The results pertaining to the within-organization educational gradient in access to work-family policies are presented in Fig. 22.4, which shows the exponentiated coefficients (odd’s ratios) of a one-unit increase in employee education predicting the perceived availability of each policy by employee’s education only (Model 1) and with all individual controls added (Model 2). Because the model included organization-fixed effects, these estimates pertain to the effect of employee education within organizations. We find support for our expectation that higher skilled employees would report higher access to flexibility policies, as Fig. 22.5 shows significant positive effects of a one-unit increase in employee education on the perceived availability of flexible work times and working from home. As Fig. 22.5 shows, the inclusion of the control variables accounts for a large part of the effect of education on access to working from home, implying that individual characteristics other than education play an important role in explaining who can work from home. Also for the third item in the category work-time arrangements, work-hour reductions, higher employee education is associated with higher perceived availability. This goes against our expectation that access to policies which are not costly for the employer nor performance enhancing would not be stratified by employee skill.

Turning to the combined availability at organizational and team level, we predicted employees’ perceived availability by the four categories of combined availability, employee education and all individual and organizational control variables. The results of the multivariate models with the individual control variables are presented in Table 22.4, organizational control variables were included in the estimation but excluded from the table.

We discuss the main effects of the combined availability on employees’ perceived access first before turning to the interactions with education. The first conclusion based on the results in Table 22.4 is that managers’ reports of availability are strongly related to employees’ perception of availability and this is particularly the case when comparing the “consistent access” category in which managers at both levels report a policy as available to the “no access” category which served as the reference. With regard to the two inconsistent categories, restricted and informal access, the picture which emerges from Table 22.4 is more mixed: Employees’ perceived availability of working from home is predicted by informal access, but not restricted access, which suggests that the team (manager) is a more important determinant of perceived availability than the provision at organizational level. Contrary to this, employees’ access to a reduction in work hours and supplemental leave is predicted by restricted access, but not informal access, pointing to the organizational level as the decisive layer. Perceived access to flexible work times is higher across all categories when compared to the reference category “no access.”

We also tested whether the educational gradient in the perceived availability of work-family policies differed across the combined availability, or in other words, whether higher skilled employees would profit more from any category than lower skilled workers or vice versa. We evaluated all interaction effects between employee education and the combined availability at organizational and team level compared to the reference category of “no access” as well as against the observation-weighted grand mean. As can be seen in Table 22.4, three out of five policies, flexible work time, working from home, and reducing hours showed a positive significant main effect of employee education, implying that higher educated employees are more likely to report these policies as available.

The results from the interactions (results not shown, available upon request) show that for work-time flexibility in fact this positive educational gradient is only present in the “consistent access” category, in all other categories no difference by employee education in the likelihood of reporting access to flexible work times as available is found. For working from home and reducing work hours, no significant interaction effects are found, implying the we find a similar educational gradient across all categories of combined availability. With regard to supplemental leave, interaction effects point to a positive educational gradient in the category of “restricted access” and (slightly) negative educational gradients in the other categories, which explains the absence of a main effect of education. This points to higher skilled workers being better informed about policies when their direct supervisor is not aware of a policy. This could be related to higher educated workers being more likely to work in white-collar positions in which access to information about employee benefits is easier accessible.

For childcare assistance, we do not have information about provision at the team level, but we nevertheless estimate an interaction between access reported by the HR manager and employee education to predict perceived availability of childcare assistance. Similar to the results obtained for supplemental leave, the estimates point to a positive gradient when childcare assistance is provided at the organizational level, but no differences by education when no provision is reported. Again, this explains the absence of a significant main effect of employee education. Like in the case of hour reductions, it also points to an information advantage among higher skilled workers.

The individual-level control variables show effects related to two of the alternative explanations offered in the literature, need for support, and relative bargaining power. The first applies to access a reduction in work hours, supplemental leave, and childcare assistance, which are all significantly more likely to be reported as available by respondents with young children in the household. Women are more likely to report that work-hour reductions are available at their organization. In line with previous research, access to working time arrangements is predicted by indicators of higher relative bargaining power: income and occupational status. It is interesting to note that a higher amount of autonomy predicts higher access to all five policies considered. This indicates that this item captures not only practical aspects being able to work flexibly and thus make use of arrangement.

Finally, with regard to country differences we examined how far the availability of policies differed from the weighted mean of all countries (results not shown), but could not discern a clear pattern related to the statutory policies and most countries did not differ from the mean significantly.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the educational gradient in the provision of and access to organizational work-family policies while taking a multilevel perspective and examining various types of policies. More specifically we asked whether organizations with a larger proportion of highly skilled employees are more likely to provide access to organizational work-family policies and whether higher skilled employees are more likely to report access to organizational work-family policies. We find that at the organizational as well as the employee level, higher skilled employees have more access to working time arrangements which grant flexibility in the time and location of work. While at the organizational level only access to working from home shows a “net educational gradient” which persists after controlling alternative explanations, all three indicators of work-time arrangements at the employee level show “net education gaps” in access. This is in line with previous research and shows that neither the type of work nor the personal need for work-family support can explain the advantages and benefits higher skilled workers enjoy in their conditions of employment (Chung, 2018; Golden, 2008; Weeden, 2005).

Our uniquely rich data source enabled us to assess also how the provision of work-family policies at organizational and team level, independently reported by HR and team manager, relates to employee’s perceived access to the policy and examine in how far this differed by employee skills. We distinguished four categories in this multilevel perspective on the combined availability at two hierarchical levels. The two inconsistent categories of restricted (only access at organizational level) and informal (only access at team level) cover approximately one-fifth of the sample across all policies, of which two-third in the category restricted access and one-third in the informal access category. These inconsistencies which may stem from a variety of processes clearly show the importance of taking into account information from different sources for understanding workers’ access to policies.

That the overlap in reported access between the various levels of organizations is not perfect is also apparent in the finding that for all five organizational work-family policies reported access by employees is substantially lower than provision reported by the team managers, which in turn is lower than the provision reported by the HR managers. Nevertheless, we find strong relationships between access to work-family policies reported by both managers (consistent access) and employee’s perception. Although we believe that this speaks to the validity of measuring provision of policies at employee level, as is frequently done in survey research, the more mixed results for the two inconsistent categories point to complex processes in the distribution of information in organizations. While for supplemental leave and a reduction in work hours the provision at the organizational level appears to be the more important determinant of employees perceived availability of these measures than the team level availability, for working from home the team manager appears to be more decisive. The fact that a manager reports that a policy is available in the organization clearly does not imply that this is known across the organization or that employees feel they have access to a policy.

We cannot discern between employees not knowing about a policy and perceiving it as inaccessible, which unfortunately limits our deeper understanding of the processes involved and poses a limitation to our research. Moreover, there exists a trade-off between collecting detailed information which allows for deeper insights but limits the scope of a study, and covering many areas with a more superficial inquiry. While the ESWS has an exceptional scope in terms of topics covered, its multilevel design and cross-national nature, it is not always clear how reliable information from different sources in the organization is. For instance, what does it mean if an HR manager reports that a certain policy is generally available in their organization? To whom exactly does this apply and under which conditions?

As pointed out by Chung in Chapter 21 in this volume, few studies have examined the full range of work-family policies and even fewer do so in a cross-national design. To be sure, the collection of a dataset such as the ESWS which allows for such an examination is a challenging and costly endeavor. Nevertheless, it is desirable that future research invests in comparable projects that enable a comparison of different policies across countries. In order to gain deeper insights in the educational gradient in access to policies, more fine-grained questions about the information employees possess as well as their perceptions regarding access to policies for themselves and other workers should be separately assessed.

We believe that the skill-gaps in the access to organizational work-family policies identified in this chapter form an important dimension of social inequality in the labor market. A sustainable European workforce has become increasingly important in the present day. Organizational workforces are displaying growing diversity with respect to age, gender, ethnicity, and family status. Now more than ever, organizations need to consider investing in all workers to improve their performance and levels of satisfaction. These investments can take many forms, including flexible work arrangements, training plans, child-related policies, and health programs (Van der Lippe & Lippényi, 2019), but they should be distributed fairly.

Notes

- 1.

Organizational work-family policies can be part of collective agreements.

References

Allard, K., Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2011). Family-supportive organizational culture and fathers’ experiences of work-family conflict in Sweden. Gender, Work and Organization, 18(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00540.x.

Bäck-Wiklund, M., Van der Lippe, T., Den Dulk, L., & Van Doorne-Huiskes, A. (Eds.)‚ (2011). Quality of life and work in Europe: Theory, practice and policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Been, W. M. (2015). European top managers’ support for work-life arrangements. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Begall, K., van Breeschoten, L., van der Lippe, T., & Poortman, A.-R. (2020). Supplemental family leave provision and employee performance: Disentangling availability and use. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1737176.

Begall, K., & van Doorne-Huiskes, A. (2019). The institutional context of a sustainable workforce. In T. van der Lippe & Z. Lippényi (Eds.), Investments in a Sustainable Workforce in Europe‚ 17–36. London: Routledge.

Beham, B., Drobnič, S., & Präg, P. (2014). The work-family interface of service sector workers: A comparison of work resources and professional status across five European countries. Applied Psychology, 63(1), 29–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12012.

Chung, H. (2018). Dualization and the access to occupational family-friendly working-time arrangements across Europe. Social Policy and Administration, 52(2), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12379.

Den Dulk, L., Groeneveld, S., Ollier-Malaterre, A., & Valcour, M. (2013). National context in work-life research: A multi-level cross-national analysis of the adoption of workplace work-life arrangements in Europe. European Management Journal, 31(5), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.04.010.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic occupational status index. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56.

Gerdtham, U.-G., & Johannesson, M. (2001). The relationship between happiness, health, and socio-economic factors: results based on Swedish microdata. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(6), 553–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00118-4.

Golden, L. (2001). Flexible work schedules: Which workers get them? American Behavioral Scientist, 44(7), 1157–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121956700.

Golden, L. (2008). Limited access: Disparities in flexible work schedules and work-at-home. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(1), 86–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9090-7.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178.

Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2016). “It’s about time!”: Company support for fathers’ entitlement to reduced work hours in Sweden. Social Politics, 23(1), 142–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxv033.

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554.

Lambert, S. J., & Haley-Lock, A. (2004). The organizational stratification of opportunities for work–life balance. Community, Work & Family, 7(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366880042000245461.

McLanahan, S. (2009). Diverging destinies: How are children faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627.

Ortega, J. (2009). Why do employers give discretion? Family versus performance concerns. Industrial Relations, 48(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2008.00543.x.

Plantenga, J., & Remery, C. (2005). Reconciliation of work and private life: A comparative review of thirty European countries. In Media. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Präg, P., & Subramanian, S. V. (2017). Educational inequalities in self-rated health across US states and European countries. International Journal of Public Health, 62(6), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-0981-6.

Rainey, C., & McKaskey, K. (2015). Estimating logit models with small samples (Working Paper, 77843(Ml)).

Van der Lippe, T., & Glebbeek, A. (2003). Time competition survey. Machine readable dataset. Utrecht University/Groningen: ICS.

Van der Lippe, T., & Lippényi, Z. (Eds.)‚ (2019). Investments in a Sustainable Workforce in Europe. Routledge.

Van der Lippe, T., Lippényi, Z., Lössbroek, J., van Breeschoten, L., van Gerwen, N., & Martens, T. (2016). European Sustainable Workforce Survey [ESWS]. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Van der Lippe, T., Lippényi, Z., Van Lössbroek, J., Van Breeschoten, L., Van Gerwen, N., & Martens, T. (2016). “Sustainable Workforce Survey” [machine readable dataset]. Utrecht, Netherlands: Utrecht University.

Weeden, K. A. (2005). Is there a flexiglass ceiling? Flexible work arrangements and wages in the United States. Social Science Research, 34(2), 454–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.04.006.

Wheatley, D. (2017). Employee satisfaction and use of flexible working arrangements. Work, Employment & Society, 31(4), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016631447.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013)/ERC Grant Agreement n. 340045.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Begall, K., van der Lippe, T. (2020). The Educational Gradient in Company-Level Family Policies. In: Nieuwenhuis, R., Van Lancker, W. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-54617-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-54618-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)