Abstract

Occupational closure continuously establishes, contests, or reinforces institutional boundaries around occupations. Occupational closure thereby interferes with wage-setting processes in the labor market. Recent research shows a substantial impact of occupational closure on wage determination processes in Germany. However, research on occupational closure is based on the assumption that all incumbents of an occupation benefit in the same way. We challenge this assumption by showing that occupational closure works differently for different workers. Using the 2006 sample of the German Structure of Earnings Survey, we distinguish nine worker profiles (three educational groups crossed with three career stages). For each of these profiles we investigate the effects of five closure sources (credentialism, standardization, licensure, representation by occupational associations, and unionization) on the expected mean wages of occupations, employing a two-step multilevel regression model. Our results show that occupational closure does indeed differ between workers. We can show that closure plays out differently throughout employees’ careers. For example, representation through occupational associations pays off the most as employees’ careers advance. Closure sources are unequally distributed across occupations and benefit employees with tertiary degrees more than employees with vocational qualifications. Credentialism also yields the largest advantages for workers with tertiary degrees regarding wage rents. However, our analyses also point to complex interactions between credentialism and standardization, demanding further research, to investigate the interplay between individual worker characteristics and the various sources of occupational closure.

Zusammenfassung

Berufliche Schließung etabliert, verändert und verstärkt institutionelle Barrieren, die den Zugang zu Berufen regeln. Damit beeinflusst berufliche Schließung auch den Prozess der Lohndeterminierung im Arbeitsmarkt, wie jüngere Studien auch für Deutschland mehrfach nachgewiesen haben. Allerdings geht diese Forschung in der Regel von der Annahme aus, dass berufliche Schließung alle Inhaber eines Berufs in der gleichen Weise bevor- oder benachteiligt. Im Gegensatz dazu zeigt dieser Aufsatz, dass sich berufliche Schließung für verschiedene Arbeitnehmergruppen in unterschiedlicher Weise auswirkt. Mit den Daten der Verdienststrukturerhebung 2006 unterscheiden wir neun Arbeitnehmerprofile (drei Bildungsgruppen in drei unterschiedlichen Karrierestufen), für die wir jeweils mittels eines zweistufigen Multilevelregressionsmodells den Effekt von fünf Schließungsmechanismen (Credentialismus, Standardisierung, Lizensierung, Repräsentation durch Berufsverbände und Repräsentation durch Berufsgewerkschaften) auf die mittleren Löhne in den Berufen untersuchen. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass sich die Effekte beruflicher Schließung in der Tat zwischen Arbeitnehmergruppen unterscheiden. Wir können zeigen, dass sich Schließungseffekte zwischen Karrierestufen unterscheiden. Beispielsweise zahlt sich die Repräsentation durch Berufsverbände besonders für Arbeitnehmer in späteren Karrierestufen aus. Die Quellen der beruflichen Schließung sind zwischen Berufen ungleich verteilt und bevorteilen Arbeitnehmer mit tertiären Bildungsabschlüssen stärker als Arbeitnehmer mit beruflichen Bildungsabschlüssen. Credentialismus verhilft vor allem den Arbeitnehmern mit tertiären Abschlüssen zu Einkommensvorteilen. Allerdings weisen unsere Analysen auch auf komplexe Interaktionen zwischen Credentialismus und Standardisierung hin, die weitere Untersuchungen erfordern, welche das Zusammenspiel von individuellen Arbeitnehmercharakteristiken und den unterschiedlichen Quellen beruflicher Schließung offen legen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A growing body of research shows that occupational closure influences the wage determination process. Wages not only depend on workers’ productivity but also on their ability to get access to closed positions, because closed positions constrain competition with other workers. The “invisible hand of the market,” which guarantees the equivalence of wages and workers’ marginal productivity, is suspended for these positions.

Occupational closure refers to the varying degrees of bargaining power held by employees and employers in different occupations (Stuth 2017, pp. 31 ff). Especially in Germany, employers rely on occupations that signal proficiency in occupation-specific tasks to reduce transaction costs (Kerr 1954; Beck et al. 1980; Abraham et al. 2018). While these occupation-based signals may reduce search costs for employers (Spence 1973), they may also fuel competition between employers who are looking for employees with similar occupation-specific qualifications (Van Maanen and Barley 1984; Tolbert 1996). Research on occupational closure additionally stresses the fact that boundaries between occupations might increase wages and create occupation-specific rents (e.g., Haupt 2012; Bol and Weeden 2015). These barriers may consist of legal rules—as is the case with occupations that require state-granted licenses (e.g., Weeden 2002; Kleiner and Krueger 2010; Haupt 2016a)—or they may be socially constructed and employers require specific credentials as proof that candidates have the required qualifications and skills (e.g., Weber 1978, p. 1000; see also Parkin 1979, p. 58; Freidson 1994, p. 160).

Most research has so far assumed that occupational closure works the same way for all members of a given occupation (for an exception, see Drange 2013). We challenge this assumption by arguing that occupational closure mechanisms may advantage some workers more than others. For example, closure practices could favor highly educated members of an occupation more than members with a lower educational level. Moreover, occupational closure might be more important in employees’ early career stages than in later career stages.

In this paper, we uncover how occupational closure varies between worker profiles, focusing on the individual formal qualifications and career stages as the main dimensions of these profiles. Using the 2006 sample of the German Structure of Earnings Survey, we distinguish a total of nine worker profiles (three educational groups crossed with three career stages). For each of these profiles, we investigate the effects of five sources of occupational closure (credentialism, standardization, licensure, representation by occupational associations, and unionization) on the expected mean wages of occupations, employing a two-step multilevel regression model. As we assume that occupational closure works differently for men and women, we focus on male employees.

In the following, we review the literature on occupational closure and develop hypotheses about how occupational closure affects employees’ wages and about the extent to which closure effects should vary between workers’ profiles. Subsequently, we discuss the data and methods used to investigate these issues. Finally, we present our results and discuss their implications.

2 Occupational Closure

Similar to Weber’s (1978) concept of social closure, occupational closure refers to mechanisms that continuously establish, contest, or reinforce the institutional boundaries around occupations (e.g., Parkin 1979, p. 48; Freidson 1994; Weeden 2002). Drawing on the concept of rents, scholars have proposed that boundaries affect employees’ negotiating power, their labor market opportunities, and thus, their wages (Sørensen 1996; Weeden 2002; Congelton et al. 2008; Haupt 2012). Kim Weeden (2002, p. 60) has identified four different mechanisms of occupational closure that create and reinforce these boundaries: restricting the occupation-specific labor supply, increasing diffuse demand, channeling the demand for tasks and services to an occupation, and signaling quality.

The restricting-supply mechanism systematically restricts the supply of labor and prevents demand and supply from adjusting as they would in a free market; this consequently guarantees improved working conditions within certain occupations—in the form of higher pay or lower unemployment risks. Such restrictions may, for example, include employers’ requirements that potential employees hold occupation-specific certificates (e.g., stock-market clerk credentials).

The increasing diffuse demand mechanism ensures that workers can indeed realize the gains resulting from restrictions in the labor supply. Employers have to demand a constant or even an increasing level of occupation-specific workers; otherwise, the restriction of the labor supply will have no positive effect for the workers (Weeden 2002). For example, occupational associations that successfully lobby for an overall increase in expenditure on education should increase the diffuse demand for incumbents of education-related occupations.

The channeling demand mechanism reduces competition with other occupations over their profitable task niches (Abbott 1988). For this to function effectively, the beneficiaries need to have tools at their disposal that allow them to direct the demand for specific goods or services to their occupation (e.g., licensing). If they do not restrict competition with other occupations, employers will instead hire employees from related occupations with similar sets of tasks and skills and thereby drive the closure rent down (Berlant 1975, p. 48; Weeden and Grusky 2014, pp. 482–483).

The signaling quality mechanism indicates the appropriateness of individuals for positions that involve certain tasks and skills. This mechanism is based on the idea of an occupation as a label that instantly invokes stereotypes of the set of skills that the occupational members are supposed to possess. Thus, employers can assess which individuals are best trained to perform a vacant position effectively, efficiently, and at a particular level of quality (Weeden 2002, pp. 66–67). Such signals may consist of standardized credentials that indicate a well-known practical value for employers.

Weeden (2002) introduced institutionalized closure sources as proxies for closure mechanisms because closure mechanisms are not directly measurable. Yet, it is possible to measure the strength of institutions through closure sources that create, for example, supply side restrictions. Closure sources are institutionalized occupation-based practices that trigger one or more closure mechanism and thereby help to create labor market shelters for certain occupations or ensure that occupations remain in these labor market shelters (Freidson 1994, pp. 83–84). Closure sources differ in their economic payoffs because they trigger different closure mechanisms. The following paragraphs introduce five closure sources (credentialism, standardization, licensing, representation through associations, and unionization) and their theoretical impact on individual wages.

Credentials are one of the main sources of social closure in modern societies. They are formal symbols (educational certificates issued by the vocational education and training system or by universities) indicating that the holder of the credential has achieved a certain level of competence or knowledge. If employers require employees to have occupation-specific credentials, the competition between employees will be restricted to those who hold these credentials (Freidson 1994, p. 160; see also Parkin 1979, p. 58). Hence, in credentialized occupations, the labor supply will be restricted, which will in turn increase the chance of generating rents.

Standardization means that credentials represent common standards regarding the occupation-specific skills that workers provide. Common standards are created by occupational education and training programs that follow the same standards nationwide (Allmendinger 1989, p. 233). Federal law or state laws provide these occupation-specific standards. Standardized credentials raise entry barriers: of two job candidates, employers will choose the one who has a standardized credential with well-known skills that signal instant productivity without the need for additional training periods (Abraham et al. 2011). Standardization thereby increases employers’ willingness to pay more for employees’ services (Weeden 2002). Standardization triggers the diffuse demand mechanism because the signaling value of employees’ standardized qualifications is independent of the firms and schools that initially trained them. Hence, standardized qualifications increase the employees’ mobility (Abraham et al. 2018). Employers become substitutable (Beck et al. 1980, p. 79) and employees more mobile between employers within their occupation. The competition between employers who depend on employees in standardized occupations should improve the employees’ chance of generating rents.

Licensing provides an occupational patent on specific tasks and forbids members of other occupations to perform these tasks under threat of legal prosecution (Beck et al. 1980; Weeden 2002). In other words, licensing triggers the restricting supply mechanism and the channeling demand mechanism. It thus precludes any competition between members of other occupations with members of the licensed occupation and thereby secures rents (e.g. Gittleman et al. 2015; Bol and Weeden 2015; but see Haupt 2016b; Damelang et al. 2018). It also forces employers to rely only on licensed employees for specific tasks.

Occupational associations are important actors because they are the very basis of intentional occupational closure. Occupations are not entities that become closed all by themselves. They have to become organized communities to further their incumbents’ interests through lobbying (Van Maanen and Barley 1984; Abbott 1988; Weeden 2002; Hoffmann et al. 2011; Barron and West 2013). Such lobbying attempts may aim high and push for licensure legislation. However, lobbying in Germany usually is aimed at triggering the increased diffuse demand mechanism by campaigning for laws that, for example, oblige customers to use occupational services at legally defined intervals (e.g., chimney sweepers). Furthermore, occupational associations may offer their members opportunities to create and maintain social networks and offer exclusive training opportunities; by so doing, they enhance their members’ career chances of gaining access to closed positions by invoking the signaling quality mechanism.

Finally, unionization of occupations can be conceptualized as a closure source (Weeden 2002; Gittleman and Kleiner 2013; Bol and Weeden 2015; Bol and Drange 2017). Occupation-specific unionization in Germany does not rely on exclusionary practices like the closed-shop agreements prevalent in the USA. Instead, it relies on a different closure source that was proposed by Parkin (1979): usurpationary closure. Usurpationary closure is aimed at winning greater shares of resources by using conflict to eat into the profits of the employers. In Germany, this mainly is done by collective bargaining over wages and employment conditions. Resulting collective agreements apply to all occupational members within a company and thereby establish and raise wage floors or equalize wages between workers within the same occupation (Helland et al. 2017; Budig et al. 2019).Footnote 1 Hence, unionization uncouples the demand/supply ratio from wage-setting processes. Even a high supply of train drivers or a low demand for train drivers will not impact their wages, because there is no cheaper alternative (Drange and Helland 2019).

To summarize, different closure sources trigger different closure mechanisms and thereby drive employees’ wages above the market clearing wage. Credentialism and licensing trigger the restricting supply mechanism and limit the competition between employees within the occupations to those individuals who meet the entry requirements. Occupational associations and standardized credentials increase the diffuse demand for occupational services or products. The channeling demand mechanism is triggered by licensing that restricts competition between workers in licensed occupations and workers in other occupations. Moreover, credentialism, standardization, licensing, and associations trigger the signaling quality mechanism. Finally, unionization is an usurpationary closure source that uses conflict to directly impact the wage setting process.

3 Why Different Workers Benefit Differently from Occupational Closure

Research on the effects of occupational closure has assumed that it has more or less the same advantages for all incumbents of an occupation. We believe that this assumption is too strong and assume that workers with different levels of educational certificates and workers at different career stages should benefit differently from occupational closure.

As regards the levels of educational certificates, we distinguish between workers with tertiary degrees, workers with vocational qualifications, and workers with no vocational qualifications. Educational certificates from each of these levels would open the way to a certain range of occupations. However, employers are free to decide who to hire (exception: licensed occupations). For some occupations, employers may recruit workers from any of the three educational levels (e.g., “publicist” is a broad occupational category, in which workers from all sorts of educational backgrounds may be employed). For others, strong ties between occupations and educational levels exist, because of minimum skill requirements and/or closure processes (DiPrete et al. 2017).Footnote 2

For each of the educational groups, employees in closed occupations should be better off than employees in open occupations with regard to wages. However, we expect advantages of occupational closure to be larger for workers with tertiary degrees for two reasons. First, these workers are more productive, thereby generating higher revenues, which allow for higher wage rents for the closed occupations. The proverbial cake that is to be distributed corresponds in size to the employees’ level of productivity. Second, the closure strategies available to employees with tertiary degrees are more effective than the closure strategies available to employees with no vocational qualifications (Groß 2012). Labor market research conventionally refers to what Parkin (1979) calls “exclusionary” closure when it addresses occupational closure. Exclusionary closure generates rents through securing privileged positions at the expense of other groups (e.g., Weeden’s (2002) closure sources). Exclusionary closure is directed downward. Hence, employees who are already at the bottom in the labor market hierarchy will not profit much from it. Instead they must use “usurpationary” closure to direct their power upward to gain higher wages. Usurpationary closure is aimed at winning greater shares of resources by using conflict to eat into the privileges of superior groups (privileged occupations) or the resources of employers.

As shown in Fig. 1 we expect closure sources that are exclusionary (credentialism, standardization, licensing, and occupational associations) to be most effective for employees with tertiary degrees, whereas unionization as a usurpationary closure source should be most effective for employees without qualifications. For employees with vocational qualifications, both usurpationary and exclusionary closure should be moderately effective. Thus, we conclude that occupational closure is education-specific and that the five closure sources we investigate in this article differ in their functioning for the different educational groups.

We also expect effect heterogeneity along workers’ career stages. Occupational closure should in most cases strongly affect employees’ initial job placement, as entrants can instantly benefit from the exclusion of competitors from their occupations. However, in later career stages occupational closure may work very differently. Some closure sources may intensify their wage effects as careers progress, whereas the impact of other closure sources on wages may decrease over one’s working career. For example, while networking opportunities provided by occupational associations may pay off only after some time, credentialism should pay off most in early career stages.

4 Hypotheses

We draw hypotheses about the wage effects of each of the five closure sources and consider their interaction with workers’ education and career stage.

For credentialism, the ideas outlined above apply in a straightforward manner:

H1a

As credentialism generates closure rents, it affects wages positively. The advantages are greatest for workers with tertiary degrees and smallest for workers without vocational qualifications.

H1b

As credentialism becomes less important in later career stages and other sources of accumulated human capital become more important (Witte and Kalleberg 1995, p. 311), credentialism should pay off most in the early career stages (Haupt 2012).

The degree of standardization of employees’ credentials varies and provides employers with different signals of quality (Stuth 2017; Abraham et al. 2018). Employers should be willing to pay more for employees with credentials that are highly standardized, thereby signaling an unambiguous level of quality and productivity. Standardization is enhancing or defending demand for an occupation’s work. In addition to activating the increasing diffuse demand mechanism, employees in standardized occupations should benefit from occupational labor markets, which are more accessible for employees with tertiary degrees.Footnote 3 Their potential between-employer mobility should increase the competition between employers, increasing their bargaining power and their wages.

H2a

Standardized occupations should positively impact the wages of their incumbents. This positive effect should be more pronounced for employees with tertiary degrees than for employees with vocational qualifications (Parkin 1979).

However, standardized credentials may not be positive for employees in early career stages. Standardized credentials render employees substitutable, because they can be easily replaced by other workers also holding standardized credentials (Abraham et al. 2018). While this assumption holds generally true for all labor market entrants, the competitive pressure is even worse in standardized occupations, where potential job candidates do not require additional training to be productive. A wage bonus is instead offered to labor market entrants in unstandardized occupations to secure the employers’ investments in their human capital and thus bring them to a maximum level of productivity (Van de Werfhorst 2011, p. 526; Haupt 2012). Thus, standardization interferes with employers’ investments in employees’ human capital (Stuth 2017, pp. 162).

H2b

We assume that standardization has a negative wage effect in employees’ early career stages.

Licensing is known to compress the wage distribution in Germany (Haupt 2016b; Haupt and Witte 2016), because in most licensed occupations the prices are fixed by the government. Employees in licensed occupations may thereby be disadvantaged compared with high earners in nonlicensed occupations, but should be advantaged compared with low earners in nonlicensed occupations.

H3a

Licensing establishes an income ceiling that should negatively affect the wages of employees with tertiary degrees. However, the fixed prices in licensed occupations should positively affect the wages of workers with vocational qualifications.Footnote 4

We assume career-specific wage effects of licensing: regulated prices should be beneficial in early career stages but should be a disadvantage in late career stages, because career-specific wage progression is no issue for the regulation of prices in licensed occupations.

H3b

Licensing establishes fixed prices that may be favorable in early career stages, but presents employees with an income ceiling that negatively affects wage increases over the career. This should be true for employees with vocational qualifications and with tertiary degrees.

Occupational associations are organized communities that represent their occupation members’ interests (Larson 1977; Van Maanen and Barley 1984; Abbott 1988; Weeden 2002).Footnote 5 First, they act as lobby groups. Second, they increase and/or maintain the level of professionalization of the occupational incumbents through (a) further education and (b) professional networks. They thus trigger the increasing diffuse demand mechanism and the signaling quality mechanism. This is the only closure source for which the effects should be identical for the three educational groups.

H4a

Occupations that are represented by occupational associations should pay better on average than occupations that do not have such organized representation of occupational incumbents’ interests. This effect should be uniform for all represented employees irrespective of their educational background.

We expect the positive effects of occupational associations to be stronger in later career stages. Occupational associations help their members to gain access to closed positions by providing professionalization opportunities for their members, i.e., through further education and social networks.

H4b

Additional training and networking opportunities provided by occupational associations should signal quality and hence improve their members’ chances getting a foothold in better paid closed positions in later stages of their career.

Unionization relies on collective bargaining to win greater shares of the employers’ resources, which increases wages for all occupational members (e.g., Bol and Weeden 2015). Unionization should be most effective for occupations whose employees have no vocational qualifications (Parkin 1979). Members of low-qualification occupations are at the bottom of the labor market hierarchy and their best chance of improving their position is by directing their power upward to gain access to the resources of privileged groups (Groß 2012).

H5a

Members of occupations that are represented by unions should receive a wage premium; these premiums should be larger for workers without vocational qualifications.

We do not expect unions to generate closure rents that differ between career stages. Instead, we assume that they are concerned about creating similar employment and wage conditions for all of the members of the occupations (e.g., Budig et al. 2019).

H5b

Members of occupations that are represented by unions should receive uniform wage premiums that are not career-stage specific.

5 Data and Variables

Our empirical analysis is based on the 2006 sample of the German Structure of Earnings Survey (GSES, Verdienststrukturerhebung, see Günther (2013) for an extensive description). The GSES is a cross-sectional linked employer–employee dataset, which was sampled in two stages: In the first stage, firms were randomly drawn from the business register within each federal state of Germany (Bundesland). In the second stage, individuals were sampled within the selected firms. There was no censoring of the wage information. We restricted our analyses to male employees in western Germany who were aged 16–58 and worked at least 18 h per week, excluding workers who are still in vocational training.Footnote 6 We also excluded workers who belong to the Nomenclature of Economic Activities (NACE) category education (Klassifikation der Wirtschaftszweige 2003) because for these workers a different mode of data collection was used. Moreover, we excluded civil servants (Beamte), who are completely protected from market competition, establishing closure that focuses on employees but not occupations.

The GSES provides information about general occupational fields (Berufsordnungen) based on the German Dictionary of Occupational Titles (three digits, KldB 1988), which allows a high level of differentiation between tasks but not between different levels of task complexity and hierarchy. Hence, there is still heterogeneity within the occupational fields. However, we disentangle the vertical dimension from within the occupational fields by stratifying our sample for employees with tertiary degrees, vocational qualifications, and employees without vocational qualifications.Footnote 7 Within each stratum of employees, we included occupations with a minimum of 30 observations. We excluded occupations within the strata that were the product of miscoding or gross education–occupation mismatches (e.g., medical doctors without tertiary degrees). With respect to the latter exclusions, we conducted robustness checks by running all analyses with all occupations, irrespective of them being miscoded or mismatched. As it turned out, the results did not change in a substantive manner.

Applying all these restrictions left us with a total of 589,218 observations at the individual level. Stratifying this sample by the three education groups resulted in three subsamples that consisted of 94,734 workers with tertiary degrees nested in 80 occupations, 417,163 employees with vocational qualifications nested in 175 occupations, and 77,321 employees without vocational qualifications nested in 118 occupations.

5.1 Variables at the Individual Level

The outcome variable at the individual level was gross (logged) hourly wages. To account for different compositions across occupations with respect to workers’ characteristics and consider the features of the employment relations, we regressed (log) wages on age and age squared (as a proxy for labor force experience), tenure, type of contract (permanent versus temporary contract), and part-time status. The assumed effect heterogeneity of occupational closure was considered by, first, stratifying the analysis according to the three groups, constituted by the level of formal education. Second, to reflect different career stages, we created three career groups: labor market entrants, mid-career workers, and late-career workers. This was done by combining typical age–tenure combinations within each of the educational strata we were considering (for example, for workers holding tertiary degrees, a mid-career worker was defined as being 36 years of age and as having 6 years of tenure).Footnote 8 In addition, we used the education-specific sample means of age and tenure to create a group reflecting the “average worker” in each of the education strata.

5.2 Variables at the Occupational Level

At the occupational level, our main focus was on the effects of the five closure sources discussed in the theoretical part of this paper. In addition to these closure measures, we controlled for a number of other occupation-specific characteristics, which are described in the following paragraphs.

Credentialism was operationalized using the BIBB/BAUA data from the year 2006. Based on the employee question “What qualification is normally required to do the job you have now?” we calculated the occupation-specific percentage of employees who are required to hold a vocational qualification or tertiary degree (Bol and Weeden 2015). Occupations are coded as “closed” if the share of workers indicating the need for credentials to fulfil the jobs’ requirements is 90% or higher.Footnote 9

The degree of standardization was determined by the legislative level at which the curricula in question are standardized.Footnote 10 In Germany, curricula may be standardized at the federal level (highly standardized), the state level (moderately standardized), and the school/university level (not standardized). Based on thorough research on the degree of standardization for each credential, we created an index of standardization. The index took a value of 3 for credentials that are highly standardized, a value of 2 for moderately standardized credentials, and 1 for unstandardized credentials.Footnote 11 We used a binary version of this indicator that differentiates between occupations with a high degree of standardization (values greater than 2 on the standardization index) and occupations with a low degree of standardization.

In Germany, licensure typically refers to the protection of occupational tasks and to the protection of occupational titles. Task licensure provides a legal monopoly on specific tasks (e.g., only medical doctors are allowed to perform as medical doctors), whereas title licensure only restricts how individuals may represent themselves (e.g., occupational titles such as scientist, detective, biologist, or actor are not protected and may be used freely). We focused on task licensure. Based on information contained in the appendix of Haupt (2016a), we identified each occupation in Germany to which task licensure applies. Task licensure applies to all members of an occupation. However, a mismatch arises, because we analyzed occupations at an aggregated three-digit level. This causes researchers to change to continuous licensure measures to account for this mismatch (e.g., Weeden 2002; Hoffmann et al. 2011). We encountered the same problem, but less than 5% of our occupations had a non-integer value on the licensure variable. That meant that over 95% of the occupations still had a value of either 1 or 0. The very uneven distribution of occupations contradicts the use of a continuous measurement approach. For this reason, we decided to re-dichotomize the licensure variable. We counted each three-digit occupation where task licensure appeared as licensed.

Based on a survey on occupational associations (Schroeder et al. 2008, 2011) and the subsequent refitting of the data for the analysis of occupations (Stuth 2017, p. 90), we were able to discern whether or not occupations are represented by occupational associations. Occupational associations represent detailed occupations. Hence, we again had mismatch, which transformed the dichotomous representation variable (i.e., whether or not an occupation is represented by an association) into a continuous variable (the percentage of occupational incumbents represented by an association or not). The same problem as with licensure arose. The majority of occupations still took either the value of 0 or the value of 1. We solved this problem by re-dichotomizing the association variable too.

Unionization is usually not taken into account in studies of Germany for at least three reasons: unions typically operate at the industry level (Hipp et al. 2015), closed-shop agreements have never been allowed, and apprenticeship programs are not run by unions (Stuth 2017, p. 68). Hence, it is hard to explain how unions might trigger the restricting supply mechanism at an occupational level (Haupt 2016a, p. 74). However, some occupations in Germany operate only at the occupational level (Greef and Speth 2013). These occupation-specific trade unions represent, for example, aircraft pilots or train drivers. The survey on occupational associations described above also gathered information on the occupational associations’ right to collectively bargain. It was thus possible to identify occupations that are represented by occupation-specific trade unions. However, the same problem as with licensure and associations arose: 96% of the occupations had a value of either 1 or 0. Therefore, we re-dichotomized the unionization variable too.

Studies on the effects of occupational closure on wages have highlighted the importance of controlling for occupation-specific tasks (Bol and Weeden 2015; Giesecke and Verwiebe 2009). We used data on occupational tasks from the BIBB/BAUA 2006 survey to construct five task measures (Spitz-Oener 2006): nonroutine analytical tasks (e.g., doing research), nonroutine interactive tasks (e.g., advising and informing), routine cognitive tasks (e.g., measuring), routine manual tasks (e.g., monitoring and operating machinery and equipment), and nonroutine manual tasks (e.g., nursing). At the aggregate level of the occupation, we used the (average) responses from workers found in occupation X, who state that they frequently perform task Y. A detailed coding scheme of these task measures can be found in Table 2 (see Appendix).

To account for compensating wage differentials that reflect different levels of physical effort across occupations, we introduced a summary measure at the level of physically demanding conditions (e.g., working standing up) reported by workers. The measure is based on the BIBB/BAUA 2006 data and is similar to that used by Bol and Weeden (2015).

Gender composition and ethnic composition usually have a great impact on occupational wages (e.g., Kilbourne et al. 1994; Gartner and Hinz 2009; Haupt 2012). Based on the full sample of the German Microcensus 2006, we measured the percentage of women and the percentage of employees with non-German nationality within the occupations. Moreover, as supply–demand ratios tend to differ greatly between occupations, we included a measure for occupation-specific unemployment. This measure was also based on the Microcensus and captured the ratio between unemployed males below the age of 64 who were not in employment but were available and searching for work, and who were last employed in a specific occupation and all male members of this occupation (irrespective of their employment status).Footnote 12

5.3 Statistical Method

We applied multilevel models with two levels (individual and occupational levels) implemented in a two-step estimation procedure. We used a two-step procedure instead of a simultaneous estimation because it offers a more flexible specification, since all individual-level effects are allowed to vary across occupations as well as educational groups without imposing any further distributional assumptions. Simultaneous multilevel models that assume a multivariate normal distribution of the error terms did not converge because of our complex data structure, which included a large number of cross-level interactions and error terms.

The two-step procedure was implemented as follows. The first step involved running separate (i.e., stratified) occupation-specific regression estimations for each of the three educational groups defined above. Moreover, these regression models allowed us to estimate (adjusted) average wages for three different career groups (labor market entrants, mid-career workers, and late-career workers) as well as the group of the “average worker.” Using three education groups and four career groups, we obtain a maximum of twelve sets of estimates based on stratified (strata: educational group e) individual data for individuals i nested in occupation o:

where o and e are indicators for the grouping on occupation and education respectively, k represents the k-th individual-level variable, and c corresponds with the indicator of the career group. We estimate β0oec by employing education-specific age–tenure combinations, re-centering the age and tenure variables accordingly and holding type of contract and part-time status constant at values “permanent contract” and “no part-time” respectively.

In the second step, we examine the impact of occupation-specific characteristics on the group-specific mean estimates of wages:

where \(\hat{\beta }_{0\mathrm{oec}}\) is the estimated dependent variable (group-specific average wages from first-stage model) for education-career subgroups e and c in occupation o. This variation is modeled as a function of Q occupation-level variables Zq and an occupation-level error term uec. The Q occupation-level variables contain the measures of occupational closure and the controls discussed above.

Finally, as we use estimated parameters from the first stage as dependent variables in the second stage, we implement an estimated dependent variable (EDV) correction by a feasible generalized least square (FGLS), as suggested by Lewis and Linzer (2005). In this way, we can account both for uncertainties stemming from the first-step mean estimation and the occupation-level error term from the second-step regression.

6 Descriptive Results

We developed the idea that occupational closure works differently for different kinds of workers and that most closure sources should be much more available to workers with tertiary degrees (see Fig. 1). Moreover, we expected that closure strategies would pay off differently for different worker profiles.

In Fig. 2 we present a summary of our main explanatory variables, which provide evidence pertaining to this first expectation.Footnote 13 The general pattern emerging from Fig. 2 is that occupations performed by employees with tertiary degrees have higher degrees of closure than occupations performed by employees with vocational qualifications or workers without vocational qualifications. We find that most of the occupations (70%) in which employees with tertiary education worked show a high degree of closure via credentials. In contrast, occupations performed by vocationally educated workers or by workers holding no vocational qualifications have a much lower incidence of closure owing to credentialism (46% and 32% respectively). The fact that less than 50% of the occupations performed by vocationally educated workers require a credential is surprising, because the literature hints at a much stronger connection between vocational credentials and employment (e.g., Müller and Shavit 1998; DiPrete et al. 2017).

Distribution of occupational closure source across education groups (x axis depicts relative frequency of the binary measures of occupational closure). (Source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Länder, German Structure of Earnings Survey 2006; German Microcensus 2005–2007; BIBB/BAUA 2006; own calculations)

Higher rates of occupational closure for occupations performed by more highly educated workers can also be found with respect to licensure: while in total only some occupations are licensed, we find restrictions based on licensure in 20% of those occupations performed by employees holding tertiary degrees, whereas very few (6%) of the occupations whose employees hold vocational qualifications are licensed. Workers without vocational qualifications are by definition not allowed in licensed occupations because licenses are combined with occupation-specific credentials.

Strong education-based differences in the incidence of closure can also be found for occupational associations. Almost two-thirds of the occupations in which employees with tertiary education worked were represented by occupational associations. This is in stark contrast to the other education groups, for whom representation by associations was available in less than one-third and less than one- quarter of occupations performed by employees with vocational qualifications and no vocational qualifications respectively.

Occupation-specific trade unions can be found more often in the upper layer of occupations (20%) than in the middle and lower layers of occupations (about 10%). That occupation-specific trade unions are uncommon is not surprising, because Germany has always been dominated by industry-specific trade unions, whereas occupation-specific trade unions are still trying to legally establish their bargaining rights.

A notable exception to the general pattern of higher rates of closure for those occupations performed by more highly educated workers is standardization. Standardized educational pathways to occupations are actually more common in the lower layer of occupations: 86% of occupations in which we find workers having no vocational qualifications were standardized, 78% of the occupations pursued by workers with vocational qualifications were standardized, and “only” 47% of the occupations whose incumbents have tertiary degrees were standardized. This reflects the fact that many subjects at universities do not follow standardized curricula. The finding that standardization was much more common in the lower layer than in the middle or upper layer might imply that this potential signal of quality has become tainted or maybe even stigmatized.

Figure 3 shows the differences in the expected mean (logged) wages of open and closed occupations separately for the three educational groups.Footnote 14 As wages were measured on a log scale, the differences plotted in Fig. 3 approximately reflect advantages enjoyed by those workers in closed positions in relative terms; of course, this implies much larger discrepancies in absolute terms. As becomes apparent from Fig. 3, the mean wages were highest for workers with tertiary degrees and lowest for workers without vocational qualifications. These huge differences mirror the differences in the productivity levels of the three groups—the different amounts of “cake” that can be redistributed by occupational closure.

Mean log wages across closure sources and education groups (full/hollow markers correspond to a high/low degree of occupational closure; mean log wages are predicted for full-time workers holding permanent contracts and are averaged across career stages). (Source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Länder, German Structure of Earnings Survey 2006; German Microcensus 2005–2007; BIBB/BAUA 2006; own calculations)

In most cases, closure pays off as expected: credentialized occupations and occupations that are represented by occupational associations or occupational unions yield greater average pay for their incumbents—net of individual characteristics. For example, the wages of workers in highly credentialized occupations are on average about 10% higher than wages found in noncredentialized occupations—regardless of their educational level.

For credentialism and standardization, we expected the positive effects of closure to be largest for workers with tertiary degrees. The results support this notion in the case of credentialism, even though employees without vocational qualifications benefit nearly as much from credentialism as employees with tertiary degrees. In contrast, there is no support for our hypothesis that standardization has a positive wage effect. For unionization and licensure, we expected the effects to be larger for education groups that had a lower level than tertiary education. The descriptive analysis provides some support for this notion in the case of occupational unions. Finally, we hypothesized the effect of occupational associations to be uniform across educational groups. This notion is only partly supported by the data, as the corresponding advantage for the more highly educated group seems to be considerably larger.

Yet, all these patterns may result from the correlation of various closure indicators with each other, and/or the correlation with other important determinants of wages at the occupational level. Therefore, we ran regression models at the occupational level that control for many of these occupational characteristics and differentiate workers’ profiles according to career stages.

7 The Effects of Occupational Closure on Wages

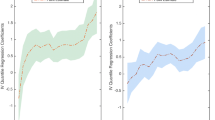

In this section, we present the results of a two-stage regression. In the first step, we regressed the hourly wages of the employees on age, tenure, type of work contract, and part-time status for each occupation–education combination. Within each of the three education strata we repeated these regressions three times to get predictions for the expected mean wages, reflecting the different career stages of the workers. A fourth regression predicts the wages for the “average” worker for the education groups. In Fig. 4, the results of the second-stage regressions are summarized, focusing on the closure indicators.Footnote 15 All effects are controlled for occupational task characteristics, occupational segregation (with respect to sex and citizenship), and occupation-specific unemployment rates.

Regression estimates of the effects of closure sources on wages I (point estimates and 95% CIs; regression models additionally control for occupational tasks, physical effort, occupation-specific share of women and non-Germans, and occupation-specific unemployment rate). (Source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Länder, German Structure of Earnings Survey 2006; German Microcensus 2005–2007; BIBB/BAUA 2006; own calculations)

We expected the effects of credentialism on wages to be strongest for workers with tertiary degrees as well as for labor market entrants (H1a and H1b). We find a positive and almost statistically significant effect of credentialized occupations on wages for the “average worker” (i.e., not distinguishing between career stages) among persons with tertiary degrees. For the other two education groups, the corresponding estimated effects are close to zero. Moreover, in direct comparison, the effect for the average worker with tertiary degrees is significantly larger than the corresponding effect for workers with vocational qualifications, while the difference does not reach statistical significance when effects are compared between the tertiary degree and the “no vocational qualification” groups (see Appendix).

Among persons with tertiary degrees, wage gains from working in highly credentialized occupations do not seem to vary across career groups. The estimated gains are about 10%, but estimates for the mid- and late-career workers are statistically more uncertain than the estimate for early-career workers. Compared with the descriptive results discussed above, we do not find any positive wage effects of credentialism for workers with a vocational qualification or for workers with no vocational qualifications in the full model. In these groups, we even find a negative effect of credentialism for entrants, although these effects are very small and do not reach statistical significance at all.Footnote 16 Thus, the results only partly support our hypotheses: the advantages of credentialism are largest for workers with tertiary degrees, but we do not find support for the notion that these wage gains decline as careers progress (see Appendix for corresponding statistical tests).

With respect to the effects of standardization, we find the strongest effects for workers with tertiary degrees. For “average” workers with tertiary degrees, the wage premium when working in occupations with a high degree of standardization is estimated to be about 17%. In contrast to the positive wage effects for workers with tertiary degrees, we find zero wage effects for the average worker with vocational qualifications and for workers without vocational qualifications. These results, as well as those of the corresponding significant tests, support H2a. However, H2b is at most partly supported by the data. In contrast to the expected negative wage effect of standardization for labor market entrants, workers with tertiary degrees are estimated to receive a small, but not significant wage premium in their early career stages when working in standardized occupations (about 5%). This wage premium increases with labor market experience and is highest in the late career stage (21%), and the difference in the underlying coefficients is statistically significant. For labor market entrants with vocational qualifications, a high degree of standardization is associated with a lower wage (minus 6%), which is in line with H2b, although the effect does not reach statistical significance. This negative wage effect vanishes over workers’ careers. Finally, we find a somewhat erratic pattern among employees who have entered the labor market without vocational qualifications, as their wage losses due to standardization are smallest in the mid-career stage and largest in the late-career stage, but none of these coefficients is statistically significant. Thus, these results clearly do not support H2b.

As far as licensure is concerned, we expected that licensed occupations would favor workers with vocational qualifications, but would lower the wages of workers with tertiary qualifications (H3a) through wage compression. Although effects are not statistically significant at conventional levels, the point estimates indicate a relative wage loss for “average” workers with tertiary education but also for “average” workers with vocational education. Thus, wage ceilings seem to negatively affect wages for all workers in licensed occupations, irrespective of their level of education compared with employees in nonlicensed occupations. At the same time, we do not find consistent results showing increasing wage losses over the career (although for workers with vocational qualifications, the estimates seem to indicate such a pattern). Thus, hypothesis H3b is not supported by the data. As we analyze only employees and exclude the self-employed, it is, however, important to note that these findings are based on the subpopulation of employed workers in licensed occupations.Footnote 17

We expected that workers in occupations that are represented by occupational associations would earn higher wages than members of occupations without association representation. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the effect on wages would be the same across education groups and larger for workers in later career stages (see H4a and H4b). Indeed, average workers in occupations that are represented by occupational associations earn more than workers in occupations without association representation (a wage gain of about 6–13%). At the same time, the differences between educational groups are not statistically significant (see Appendix). Moreover, we find positive and increasing wage gains for more experienced workers. The estimated wage gains for senior workers range from about 9 to about 20%, with effects being statistically significant in all groups. With the exception of workers with higher education, who already receive wage gains in early career stages, the wage gains from occupational associations increase over a worker’s career (differences between career groups are statistically significant, see Appendix). Overall, the clear pattern of growing advantages throughout a worker’s career, as well as similar results across education groups, supports hypotheses H4a and H4b.

Finally, with respect to occupational unions, we expected positive effects of unionization on wages that are larger for workers with low education (H5a) but that do not vary over career stages (H5b). We do not find any substantial or statistically significant effect of occupational unions on workers’ wages, irrespective of the employees’ level of education (which contradicts our hypothesis H5a) or workers’ career stage (which is in line with hypothesis H5b).

7.1 Standardization vs Credentialism

This section is aimed at shedding more light on the results for the wage effects of credentialism and standardization for workers without tertiary degrees. For these workers, the two closure sources may have different functions than for the group of workers holding tertiary degrees. This may then result in the fact that the exclusive or the joint occurrence of credentialism and standardization affects wages of workers in the three education groups differently. We are testing this idea by allowing an interaction between standardization and credentialism in the model (see Fig. 5 and Table 6 in the Appendix).Footnote 18 The results show that credentialism and standardization have positive effects on wages, but, indeed, these effects do not always add up.

Regression estimates of the effects of closure sources on wages II (point estimates and 95% CIs; reference category: not credentialized, not standardized; regression models additionally control for other closure sources, occupational tasks, physical effort, occupation-specific share of women and non-Germans, and occupation-specific unemployment rate). (Source: RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Länder, German Structure of Earnings Survey 2006; German Microcensus 2005–2007; BIBB/BAUA 2006; own calculations)

For workers with tertiary degrees in earlier career stages, credentialism or standardization grants small advantages to the occupation’s incumbents. Only if occupations are credentialized and standardized do their advantages become substantial. As we have seen before, for this educational group the effects of credentialism and standardization increase over the career, leading to substantial and statistically significant effects for the late-career stage. However, the joint (interaction) effect of these closure dimensions (48% wage gain) does not correspond to the simple sum of the underlying “main” effects of credentialism and standardization (41% and 27% wage gain respectively).

For average workers with vocational qualifications, we find small to moderate positive wage effects of standardization or credentialism, the latter closure dimensions having somewhat stronger effects. Notably, these advantages disappear for occupations that are standardized and credentialized at the same time.

We observe a similar pattern for workers with no qualifications. For this group, only a third of all occupations are credentialized (see Fig. 1 above), but if employees manage to get access to one of these occupations, this pays off quite strongly. However, it only applies if the occupations are not standardized at the same time. It is only for these credentialized occupations that we find a wage gain of more than 25%. These advantages are drastically reduced (and estimates become statistically insignificant) once credentialism and standardization jointly occur. Thus, similar to workers with vocational qualifications, workers without vocational qualifications in standardized and credentialized occupations enjoy hardly any advantages over those in nonstandardized and noncredentialized occupations.

8 Conclusions

With this paper, we have contributed to the still ongoing debate about occupational closure and its effect on employment outcomes and derived new insights for future work. Previous research on occupational closure assumed that occupational closure benefits all incumbents of an occupation in the same way. We challenged this assumption based on three arguments.

First, opportunities to make efficient use of closure sources vary with a worker’s educational level. We followed Parkin’s (1979) assumption that exclusionary closure sources (credentialism, standardization, licensing, and occupational associations) would be most effective for employees with tertiary degrees and most ineffective for employees without qualifications, who instead rely on usurpationary closure (unionization). Employees with vocational qualifications should moderately benefit from both usurpationary and exclusionary closure. At the same time, workers with higher educational certificates are more productive, creating more revenue, which can be redistributed by using closure sources. Thus, it seems reasonable to expect workers holding tertiary degrees to benefit the most from closure via credentialism. The empirical results support the notion of higher closure gains for workers with tertiary degrees, not only in the case of credentialism but also for closure via standardization. However, occupational closure is not always beneficial for high-educated workers, as demonstrated by our results with respect to licensing and unionization. For both closure sources, we found wage effects that were close to zero or even negative in some cases for workers with tertiary education, as well as for workers with vocational qualifications. With respect to occupational associations, our study is to our knowledge the first that documents a small but positive wage effect of occupational associations on wages in Germany. Finally, we were not able to reproduce the findings of Bol and Weeden (2015) regarding the positive wage effects of unionization. This is not surprising, given our different operationalization of unionization (we focused on occupational unions, whereas Bol and Weeden measured the impact of unions at the sectoral level).

Second, the advantages and disadvantages of occupational closure vary according to workers’ career stages. Generally, occupational closure implies restricted career mobility. On the one hand, this yields an advantage for employees, as it restricts labor supply, thereby creating opportunities to extract rents. On the other hand, closure may restrict opportunities for upward mobility and corresponding wage gains. On top of that, some closure sources are more effective at early career stages, while other closure sources only affect wages in the later stages of workers’ careers. For example, benefits provided by occupational associations only pay off in later career stages, probably through networking opportunities and additional training. Moreover, with respect to the other four closure sources, we found increasing, decreasing, and stable effects. Some of these patterns were in line with our theoretical predictions, whereas others were not. Our results demonstrate that the wage effects of occupational closure are far from being constant over a worker’s career.

Third, as some closure sources have different functions for different workers, they may mutually reinforce or attenuate the way in which they affect wage levels. In particular, we investigated this issue with respect to the interaction between credentialism and standardization. For workers without tertiary degrees, the wage gains offered by credentialized occupations are fully offset if educational pathways into these occupations are highly standardized. However, this does not hold true for workers holding tertiary degrees: this group benefits from both standardization and credentialism. A potential explanation for this phenomenon is that closure via standardization triggers the “signaling quality mechanism”, but this signaling may be a double-edged sword: it yields an advantage when competing for jobs, because standardization facilitates successful matches between workers and jobs; however, it puts employees at a disadvantage, as it renders them replaceable and reduces their chances for further education and training. Our results suggest that the advantages and disadvantages of standardization are unevenly distributed among workers. For more highly educated workers, the matching function outweighs the disadvantages and thereby generates higher wages. For lower qualified workers the side-effects of standardization dominate and completely wipe out the wage gains in credentialized occupations. An alternative explanation could be that employees in the skilled trades, whose occupations are highly standardized and highly credentialized, are in an unfavorable labor market position where the advantages of closure are appropriated by self-employed master craftsmen (Bol 2014; but see Damelang et al. 2018).

Our findings contribute to future research on occupational closure in at least two important aspects. With respect to theoretical reflections about the way in which closure impacts wage levels, it is necessary to better integrate specific theoretical ideas on the very functioning of closure sources. Exactly how—that is, by which means—does occupational closure affect wages? Which groups of workers are particularly affected by closure? Are there reinforcing or offsetting effects of different closure sources? Neglecting these and related issues bears the danger that the complex nexus of occupational closure, individual characteristics and wages (or other occupational outcomes) is undertheorized.

Our results suggest that researchers should consider and model effect heterogeneity when addressing occupational closure. As we have demonstrated, the effects of occupational closure vary, both with workers’ educational level and with their career stage. For example, while there is strong empirical evidence of the positive impact of credentials on wages (Giesecke and Verwiebe 2009; Groß 2009, 2012; Abraham et al. 2011; Bol and Weeden 2015), stratifying the analyses by education may result in a more nuanced interpretation. As we have shown, credentialism is only relevant for employees with tertiary degrees, whereas employees with vocational qualifications only benefit from the credentialism closure source if the occupation in question is not standardized. Moreover, comparing wage effects of occupational closure across different samples (for example, comparisons across time) may result in incorrect interpretations if effect heterogeneity is not explicitly modelled. For example, differences in the estimated conditional effects of occupational closure between two time points might just reflect differences in the distribution of education between these two samples if closure effects vary with educational level. Simply controlling for education will not solve this problem.

Change history

24 November 2021

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-021-00804-5

Notes

In some cases, the collective wage bargaining in one company covers the majority of the occupations members, for example, the collective wage bargaining of the German Train Drivers’ Union (GDL) with the Deutsche Bahn.

Some occupations comprise more abstract occupational tasks. In this case, employees’ and employers’ interests are aligned in occupational closure: employers are willing to close positions if they cannot observe and measure employees’ productivity directly or if employees’ work relations are inseparable from each other (e.g., teamwork) (Williamson 1981, 1985).

As there are no workers without vocational qualifications or tertiary degrees in licensed occupations, we cannot investigate wage effects of licensing for this particular group of workers.

Women are excluded from the analyses, because they work more frequently in part time jobs, interrupt their careers more frequently and for longer times, and face more career obstacles (“glass ceiling”) than men. We thereby believe that our closure indicators might work differently for men and women and the education/career stage groups that we are using. We defer these analyses to additional papers.

To improve readability, we refer to these occupational fields as occupations.

For the detailed coding, see Table 1 in the Appendix.

This value is based on the median of credentialism.

Hoffmann et al. (2011) and Vicari (2014) conceptualize standardization by looking at the regulation of examinations. We follow Gamoran (1996), who argues that standardized curricula provide a stronger signal than standardized examinations, because the whole process of training is standardized and not only the final examinations.

A detailed description of the operationalization (e.g., some occupations are accessible through more than one training track) can be found in the Appendix.

To ensure a high level of robustness of the data, we cumulated the microcensus for the years 2005–2007.

Summary statistics of all occupational characteristics can be found in the Appendix (Table 3).

Here, we focus on wage differentials between education groups, neglecting differences within these education groups that are due to career progress. The presented mean wages average the three career groups within a given education group. The estimates underlying Fig. 3 can be found in the Appendix (Table 4).

The complete results are displayed in Table 5 in the Appendix.

Bol and Weeden (2015) reported similar results.

We are presenting group-specific effects. Because the effects of the other three closure sources only slightly differ between the models with and without the interaction effect, we restrict the graphical representation to the effects of interest.

The references cited here can be found in the open access version of Stuth (2017) http://hdl.handle.net/10419/201802.

Because the training is conducted in two different places (in private businesses and in vocational schools) the apprenticeship training system is called the dual system (duales System).

These credentials are called nonrecognized because they are not regulated by the Vocational Training Act (BBiG) and the Crafts Code (HwO) (In German: berufliche Abschlüsse in Berufen, die keine Ausbildungsberufe sind).

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) classifies trade, technical, and master’s school-based credentials as ISCED 5B.

The trade, technical, and master’s schools do not provide initial occupational training but provide further intermediate training and hence require their pupils to have relevant occupational credentials and work experience to gain access to their training programs.

There are also private but state recognized universities run by the Catholic or Lutheran churches or private institutions.

There are three types of higher education institutions in Germany: the universities of applied sciences, which place a strong emphasis on practical work and application, the universities, which are research oriented, and the Colleges of Art and Colleges of Music, which are of equivalent status to universities.

The Federal Statistical Office of Germany provides data on the yearly number of successfully acquired occupation-specific credentials of the university students, school pupils, and apprentices in the various education and training tracks. Data for the apprenticeship system are to be found in Fachserie 11, Reihe 3 (vocational training). Data are available as Excel files for the years 1999–2008, except 2002. I had to rely on the printed edition for the year 2002, which I scanned and edited with special software to avoid and check for errors due to the scanning process (for example the number 7 is often misread as 1, lines shifts, etc.). Owing to changes in the survey methodology, no data on graduates are available for the year 2007. Data for vocational full-time schools (recognized), vocational full-time schools (not recognized), schools of the health-care sector, and trade, technical and master’s schools are to be found in Fachserie 11, Reihe 2 (Vocational schools). Data are available as Excel files for the years 2000–2009. Because of a time lag in the official publications, data on graduates are released with a delay of 1 year. For example: the number of graduates in the year 2000 is to be found in the release of 2001. Data for tertiary education at universities are to be found in Fachserie 11, Reihe 4.2 (Examinations at universities) and were made available by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany in a special edited Excel file that contained all years from 1999–2008.

The internet database of the Federal Labor Office of Germany was used (http://berufenet.arbeitsagentur.de/berufe/).

Federal legislation regulates the curricula, duration of training, range of learning fields, basic sectoral skills, and specific occupational skills. The federal legislation consists of the Vocational Training Act (Berufsbildungsgesetz [BBiG]) and the Crafts Code (Handwerksordnung [HwO]).

All credentials awarded by trade, technical, and master’s schools, and many credentials awarded by the vocational full-time schooling track (not recognized) are regulated by the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder.

Despite the fact that tertiary education is formally regulated by the Länder, the constitution (Grundgesetz) of Germany (Art. 5 (3) GG) guarantees the freedom of science, research, and teaching, and results in quasi-autonomous universities. The curriculum taught in one subject of study may vary not only between the Länder, but also within the Länder between universities.

For the very few credentials that are standardized at both the federal and the Länder level, the lower of the two possible values was assigned. The lower value reflects the leeway schools have in designing the curricula.

References

Abbott, Andrew. 1988. The System of Professions. An Essay on the Division of Export Labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Abraham, Martin, Andreas Damelang and Andreas Haupt. 2018. Berufe und Arbeitsmarkt. In Arbeitsmarktsoziologie, eds. Martin Abraham and Thomas Hinz, 225–259. Wiesbaden, Springer VS.

Abraham, Martin, Andreas Damelang and Florian Schulz. 2011. Wie strukturieren Berufe Arbeitsmarktprozesse? Nürnberg: Lehrstuhl für Psychologie, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. LASER Discussion Papers No. 55.

Allmendinger, Jutta. 1989. Educational Systems and Labor Market Outcomes. European Sociological Review 5:231–250.

Barron, David N., and West, Elisabeth. 2013. The Financial Costs of Caring in the British Labour Market: Is There a Wage Penalty for Workers in Caring Occupations? British Journal of Industrial Relations 51:104–123.

Beck, Ulrich, Michael Brater and Hansjürgen Daheim. 1980. Soziologie der Arbeit und der Berufe. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Berlant, Jeffrey L. 1975. Profession and Monopoly. A Study of Medicine in the United States and Great Britain. Berkely: University of California Press.

Bol, Thijs. 2014. Economic Returns to Occupational Closure in the German Skilled Trades. Social Science Research 46:9–22.

Bol, Thijs, and Ida Drange. 2017. Occupational closure and wages in Norway. Acta Sociologica 60:134–157.

Bol, Thijs, and Kim A. Weeden. 2015. Occupational Closure and Wage Inequality in Germany and the United Kingdom. European Sociological Review 31:354–369.

Budig, Michelle, Melissa Hosges and Paula England. 2019. Wages of Nurturant and Reproductive Care Workers: Individual and Job Characteristics, Occupational Closure, and Wage-Equalizing Institutions. Social Problems 66:294–319.

Bundesanstalt für Arbeit. 1988. Klassifizierung der Berufe, Ausgabe 1988 (KldB 1988). Nürnberg.

Collins, Randall. 1979. The Credential Society: A Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification. New York, Academic Press.

Congelton, Roger D., Arye L. Hillman and Kai Andreas Konrad. 2008. 40 Years of Research on Rent Seeking. Berlin: Springer.

Damelang, Andreas, Andreas Haupt and Martin Abraham. 2018. Economic consequences of occupational deregulation: Natural experiment in the German crafts. Acta Sociologica 61:34–49.

DiPrete, Thomas A., Christina C. Eller, Thijs Bol and Hermann G. van de Werfhorst. 2017. School-to-Work Linkages in the United States, Germany, and France. American Journal of Sociology 122:1869–1938.

Drange, Ida 2013. Early-career Income Trajectories among Physicians and Dentists: The Significance of Ethnicity. European Sociological Review 29:346–358.

Drange, Ida, and Håvard Helland. 2019. The Sheltering Effect of Occupational Closure? Consequences for Ethnic Minorities’ Earnings. Work and Occupations 46:45–89.

Freidson, Eliot. 1994. Professionalism Reborn. Theory, Prophecy, and Policy. Cambridge: Policy Press.

Gamoran, Adam. 1996. Curriculum Standardisation and Equality of Opportunity in Scottish Secondary Education: 1984–1990. Sociology of Education 69:1–21.

Gartner, Hermann, and Thomas Hinz. 2009. Geschlechtsspezifische Lohnungleichheit in Betrieben, Berufen und Jobzellen (1993–2006). Berliner Journal für Soziologie 19:557–575.

Giesecke, Johannes, and Roland Verwiebe. 2009. Wachsende Lohnungleichheit in Deutschland. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 19:531–555.

Gittleman, Maury, and Morris Kleiner. 2013. Wage Effects of Unionization and Occupational Licensing Coverage in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 19061.

Gittleman, Maury, Mark Klee and Morris Kleiner. 2015. Analyzing the Labor Market Outcomes of Occupational Licensing. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 20961.

Greef, Samuel, and Rudolf Speth. 2013. Berufsgewerkschaft als lobbyistische Akteure. Potenziale, Instrumente und Strategien. Düsseldorf: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. Arbeitspapier 275.

Groß, Martin. 2009. Markt oder Schließung? Zu den Ursachen der Steigerung der Einkommensungleichheit. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 19: 499–530.

Groß, Martin. 2012. Individuelle Qualifikation, berufliche Schließung oder betriebliche Lohnpolitik – was steht hinter dem Anstieg der Lohnungleichheit? Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 64:455–478.

Günther, R. 2013. Methodik der Verdienststrukturerhebung 2010. Wirtschaft und Statistik 2:127–142.

Haupt, Andreas. 2012. (Un)Gleichheit durch soziale Schließung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 64:729–753.

Haupt, Andreas. 2016a. Zugang zu Berufen und Lohnungleichheit in Deutschland. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Haupt, Andreas. 2016b. Erhöhen berufliche Lizenzen Verdienste und die Verdienstungleichheit? Zeitschrift für Soziologie 45:39–56.

Haupt, Andreas, and Nils Witte. 2016. Occupational Licensing and the Wage Structure in Germany. Working Paper Series in Sociology Nr. 4. Karsruhe: Karlsruher Institut für Technologie.

Helland, Håvard, Thijs Bol and Ida Drange. 2017. Wage Inequality Within and Between Occupations. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 7(4):3–24.

Hipp, Lena, Janine Bernhardt and Jutta Allmendinger. 2015. Institutions and the Prevalence of Nonstandard Employment. Socio-Economic Review 13:351–377.

Hoffmann, Jana, Andreas Damelang and Florian Schulz. 2011. Strukturmerkmale von Berufen. Einfluss auf die berufliche Mobilität von Ausbildungsabsolventen. Nürnberg: IAB. IAB-Forschungsbericht 09/2007.

Kerr, Clark. 1954. The Balkanization of Labor Markets. In Labor Mobility and Economic Opportunity, Hrsg. Edward Wight Bakke, 92–110. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kilbourne, Barbara, Paula England and Kurz Beron. 1994. Effects of Individual, Occupational, and Industrial Characteristics on Earnings. Intersections of Race and Gender. Social Forces 72:119–1176.

Kleiner, Morris M., and Alan B. Krueger. 2010. The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing. British Journal of Industrial Relations 48:676–687.

Larson, Magali S. 1977. The Rise of Professionalism. A Sociological Analysis. Berkely: University of California Press.

Lewis, Jeffrey B., and Drew A. Linzer. 2005. Estimating Regression Models in Which the Dependent Variable Is Based on Estimates. Political Analysis 13:345–364.

Müller, Walter, and Yossi Shavit. 1998. The Institutional Processes of the Stratification Process. A Comparative Study of Qualifications and Occupations in Thirteen Countries. In From School To Work, eds. Yossi Shavit and Walter Müller, 1–48. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parkin, Frank. 1979. Marxism and Class Theory. A Bourgeois Critique. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rostam-Afshar, Davud, and Kristina Strohmaier. 2018. Does Regulation Trade Off Quality against Inequality? The Case of German Architects and Construction Engineers. British Journal of Industrial Relations 57(4):870–893.