Abstract

The aim of the article is to reconstruct the way the concept of well-being is most commonly understood in economics, to identify deficiencies of this understanding, and to find a remedy to them. The paper defends two basic claims: (1) that the dominant understanding of well-being in economics is non-normative and boils down to the concept to utility maximisation, i.e., satisfaction of one’s preferences, whatever they are (subject, at best, to some formal constraints); (2) and that, given the shortcomings of the non-normative concept of well-being, e.g., its tautological character (at least in the case of certain formulations of this concept), it is indispensable to build an axiologically richer (that is: normative) concept of well-being, thereby going beyond the mere notion of utility-maximisation. As for the claim (2), two versions of the normative concept are distinguished in the article, viz. an exclusive one (well-being as causally dependent on prudential values but not moral ones) and an inclusive one (well-being as causally dependent on prudential values constrained in some way by moral ones), and it is argued that the latter is more plausible, since, in contrast to the former, it does not rely on a dubious assumption about the absolute priority of prudence over morality.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

11.1 Introduction

Somewhat schematically, one can say that there are three assumptions economics makes about well-being. The first one is that the economic agent is focused on what is “good for herself” (is self-interested). The second – which adds content to the first one – is that well-being is the primary criterion of evaluation of the state of affairs in normative economics: what is good for an agent equals her well-being. The third – a natural consequence of the second one – states that the economic progress of societies is evaluated in terms of social well-being usually measured by GDPper capita. As we can see, well-being is a central concept of economics. However, there are controversies as to how it should be understood. Our goal here will be to reconstruct the way the concept of well-being is most commonly understood in economics and to identify deficiencies of this understanding. More specifically, we shall argue that it is necessary to build an axiologically richer concept of well-being and that in order to do this, one has to go beyond the mere notion of utility-maximisation (which is usually assumed by economics to be definiens of well-being). If such understanding of well-being is accepted, the dichotomy of self-interested and axiological motivation of economic agents can be overcome.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 11.2 argues against a non-normative account of well-being which reduces this concept to utility maximisation, i.e., satisfaction of one’s preferences, whatever they are (subject, at best, to some formal constraints). Section 11.3 discusses two versions of a normative account of well-being: (1) well-being as causally dependent on prudential values but not moral values (an exclusive approach); (2) well-being as causally dependent on prudential values constrained in some way by moral ones (an inclusive approach). The final section concludes.

11.2 Against the Non-normative Account of Well-being

The prevalent view of well-being in mainstream economics can be dubbed non-normative, as it refers merely to utility maximisation, where utility is defined either in terms of revealed or stated preferences. Before we discuss these two versions in some detail, let us notice that both of them constitute a significant departure from the classical understanding of utility. In his popular textbook “Intermediate Microeconomics”, Hal Varian asserts that back in the Victorian days classical utilitarians and economists understood ‘utility’ as an equivalent of a person’s overall well-being identified with happiness (Varian 2010). However, this claim is not entirely correct. In fact, Jeremy Bentham (1907) says that what is meant by ‘utility’ is “that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered.” Thus, it would be more precise to say that, for him, ‘utility’ was a synonym of ‘usefulness’ (Broom 1999, 19), which can give rise to certain positive consequences (including happiness). But this is only a starting point in a complicated history of the meaning of ‘utility’ in economics. The meaning evolved from signifying a useful property of things (Bentham), through mental states of a person (pleasure, happiness), the intensity of his desires and their satisfaction (Pigou1932, 38), to its contemporary understanding – as preference satisfaction among specified alternatives. What is more, even the relationship between utility and preference satisfaction changed. As Varian (2010, 55) states: “Originally, preferences were defined in terms of utility: to say a bundle (x1,x2) was preferred to a bundle (y1,y2) meant that the x-bundle had a higher utility than the y-bundle. But now we tend to think of things the other way around. The preferences of the consumer are the fundamental description useful for analysing choice, and utility is simply a way of describing preferences. A utility function is a way of assigning a number to every possible consumption bundle such that more-preferred bundles get assigned larger numbers than less-preferred bundles.” The question of which consumption bundle is preferable to someone is answered upon the choice he or she makes. For instance, if someone consistently chooses apples when bananas are also available, an economist can infer that she prefers apples over bananas. Thus we have come to the first version of the non-normative account of well-being (in terms of revealed preferences) mentioned at the beginning of this section. In our critical analysis of this concept we shall follow, to a large extent, Amartya Sen (and we shall also use the term ‘well-being’ interchangeably with ‘welfare’ – the term Sen prefers).

The lack of a choice-independent way of understanding a person’s attitudes towards alternatives provides a rationale for what is called definitional egoism which means that “(…) all agent’s choices can be explained as the choosing of ‘most preferred’ alternatives with respect to a postulated preference relation” (Sen1977, 323). Following Amartya Sen, we can identify three dimensions of self-interested behaviour. Firstly, this view assumes that a person’s welfare depends only on his or her consumption bundle (self-centred welfare). Secondly, the only goal of a person is to maximise his or her welfare (self-welfare goal). Thirdly, people always act purposively, that is, whatever they are choosing it is directed to reach their goals according to their order of preferences (self-goal choice) (Sen 1986, 7; 1988, 80). The self-centred welfare precludes the possibility that an agent’s welfare depends on the consumption bundles of some other persons. For instance, it rules out the possibility that someone feels worried because of another person’s extreme poverty and that this feeling negatively impacts his own well-being. The self-welfare goal excludes any attachment of any positive or negative weights to other people’s welfare from the agent’s goals. The agent cannot aim to increase or diminish other people’s welfare. Finally, the self-goal choice states that the only motive behind a person’s actions is his or her desire to further their goals. All other motives, such as complying with social conventions or acting according to one’s religious and moral commitments have to be excluded.

The combination of self-welfare goal and self-goal choice allows one to infer that an agent makes his or her choice exclusively to further his or her welfare, which means that she always prefers and chooses things which enhance her own welfare (self-welfare choice). The self-welfare choice establishes choice – welfare inference by ruling out choices unrelated to the agent’s welfare, and not allowing the possibility of counter-preferential choices. The self-welfare choice, together with the self-centred welfare, completes the task of defining personal welfare on the basis of her choices. On this view, whatever one chooses, the choice will mean that it is her most preferred option and that it maximises her well-being. In other words, what is chosen by an agent is always good for her or him. Thus, definitional egoism, implied by the theory of revealed preferences, leads to the following tautological account of well-being:

The life of an agent S goes well if and only if S succeeds to choose, in the overwhelming majority of decisional situations he is faced with, the options that are the most preferred for him; and the statement that an option p is most preferred to S in a given decisional situation means that S chooses p in this situation.

The arguments against this view can be divided into two groups. The first one consists in a criticism of the assumption that the self-goal choice is true. The second group contains arguments rejecting this assumption. According to Daniel Hausman, the choice – welfare inference is doubtful even if people always make purposive choices. He points out that in order to infer welfare from an agent’s choices through her preferences, economists have to assume not only that the agent is goal-oriented and self-interested but also that she is aware of different available options, and can correctly judge what is better for her. Hausman gives the following example. “Suppose there are only two alternatives, x and y, and that x is in fact better for Jill than y. If Jill judges correctly, then Jill will rank the expected benefit of x above that of y. If Jill is self-interested, then Jill prefers x to y. If Jill knows that she can choose x or y, she will then choose x. The economist can then work backward. From Jill’s choice, the economist can infer Jill’s preference – but only on the assumption that Jill knows that she could have chosen y. From Jill’s preference for x over y, the economist can infer that Jill thinks that x is better for her than y is – but only on the assumption that Jill is self-interested. From Jill’s judgment that x is better for her than y is, the economist can conclude that x is, in fact, better for her – but only on the assumption that Jill’s judgment is correct (Hausman2011, 89).” Hausman’s analysis shows that definitional egoism, in fact, excludes the possibility that the agent’s choice could be mistaken. Given how often people are wrong about their knowledge regarding available options or correct judgements, this is a rather unconvincing assumption. Thus, Hausman concludes that a person’s choices do not determine what is good for her but can only be treated as evidence of her well-being. Even more fundamental objections against definitional egoism are raised by Amartya Sen. According to him, choice cannot be a part of the definition of an agent’s welfare because sometimes other people make choices for her. For instance, if the government decides how much money to spend on defence so that its citizens do not feel insecure, we cannot infer citizen’s well-being levels merely by looking at their choices. What is more, going beyond self-goal choice, an agent can be motivated by other reasons than her welfare (even broadly understood). Someone can follow social rules or moral norms which are against his or her preference ordering. In such a case his or her choices cannot be seen as enhancing their welfare (Sen 1980, 206).

The above definition of well-being forms a kind of non-normative view because it does not contain any reference to values (prudential or moral). However, we should be aware that the rejection of definitional egoism does not necessarily lead to the normative interpretation of well-being. There is a second version of non-normative account, according to which:

The life of an agent S goes well if and only if, in the overwhelming majority of decisional situations S is faced with, S succeeds to choose the options that are the most preferred for him; and the statement that an option p is most preferred to S in a given decisional situation means that it occupies the highest place in his ranking of preferences which is constructed or given prior to the choice.

Unlike the previous one, this account (in terms of stated preferences) avoids the objection of being tautological, because it assumes that preferences are known prior to making a choice. But it is still non-normative, as it implies that only formal requirements are imposed on an agent’s ranking of preference. In particular, a set of preferences should be complete and transitive. Preference completeness means that an agent can either prefer x over y or y over x or is indifferent between them. It is essential to distinguish between indifference and inability to rank options. If an agent is indifferent between two options, it means that each of them is equally good for him, while if he is unable to rank them, not only does he not know whether one of them is better than the other but also whether they are equally good for him. The requirement of transitivity implies that if an agent prefers x over y, and y over z he also has to prefer x over z. This requirement protects the agent from being exploited, since, as the so-called “money pump argument” shows, a person with intransitive (cyclic) preferences will be eager to engage in a series of transactions where he “(…) will have paid a positive price for a zero benefit” (Schick 1986, 116). For instance, someone who prefers x over y, and y over z, and at the same time z over x will be ready to sell x to buy y, paying an extra money, then sell y to buy z, paying an extra money, then sell z to once again buy x, of course paying extra money. The series of transactions ends up at the point when an agent is left with the same good which he had at the beginning, but with less money. Although these formal requirements are important for an agent to ensure that his life will go well, this account of well-being, as we have seen, does not make any reference to prudential or moral values. So even though it is not a tautological concept of well-being, it is still non-normative: it does not rely on any substantive (axiological) assumptions. All of this leads us to the conclusion that in order to create a richer, normative account of well-being, we have to reject definitional egoism and move beyond purely formal constraints of preference ordering.

11.3 The Normative Account of Well-being

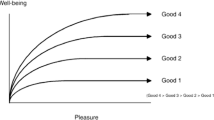

One can distinguish two ways to account for the normative conception of well-being: one in which well-being refers exclusively to prudential values, and the second in which besides prudential values well-being includes some reference to moral ones. Let us investigate them in turn.

11.3.1 The Exclusive Approach: Well-being as Unconstrained Pursuit of Prudential Values

The exclusive approach to normative well-being assumes that there is only one kind of value which contributes to a person’s well-being, namely: prudential value. If something is prudentially valuable for someone, it means that it is good for him. The general theory of what it means that x is good for y was presented by Richard Kraut (2009). He claims that to say that x is good for y, we have to know the nature of both elements of this relationship as well as whether there is a certain fit or match between them. For instance, watering is good for potted flowers or changing the oil in a car is good for the engine or having a couple of devoted friends is good for a person. To say something about what is good for a person, that is what contributes to his or her well-being, we have to gain some knowledge about him or her.

As economists usually assume, the basic facts about human beings are a reflection of the basic tenet of folk psychology – that people have some beliefs and desires. Roughly speaking, these mental entities are what enables them to form goals and make decisions which are supposed to lead them to the attainment of these goals. More technically, persons are capable of forming preferences and want them to be fulfilled. According to this view, p is good for S if and only if p satisfies S’s preference. For instance, if Eve would like to have a child and she, in fact, gives birth, then the baby is good for her. However, if she prefers not to have a child, and the reality matches her preferences, then not having the baby will be good for her. Because a person is an agent with a set of beliefs and desires, whatever is good for a person depends solely on her or his preferences. The match between a person’s preference and her preferable state of affairs depends on the occurrence of that state which guarantees satisfaction of the preference.

This somewhat formalistic view of prudential values, however, is an object of wide criticism. First of all, since a person exists in particular circumstances, her preferences can be influenced by many factors, which leads to the well-known problem of preference adaptation. What is more, preferences can be formed via indoctrination; if they are formed in this way, they cannot be regarded as a genuine reflection of wants and beliefs of that particular person. One possible answer to these objections is to move into the direction of the theory of true preferences. On this theory, only preferences created by agents who are in the proper state of mind, that is, who always reason with the greatest possible care, and have all relevant information about the states of affairs should be taken into account (Harsanyi 1977, 646).

Finally, the view that something is good for a person – is prudentially valuable – just because she prefers it, may work well in some popular examples from economic textbooks but not necessarily in real-life situations. For instance, if someone has to choose between ice-cream and chocolate (a common dilemma in many economic textbooks), it is undoubtedly true that that dessert is good for him, which he prefers most. However, in real life, people often prefer something because they are convinced that it is good for them. Following James Griffin (1993), we indicate that prudential values require going beyond the so-called taste model (that is, the view that value of things is based only on personal tastes or preferences) towards the perception model which states that in order to prefer something, a person has to recognise its value first. In other words, people should prefer something because it is valuable, not the other way around. This way of conceptualising the relations between values and preferences is assumed in Griffin’s account of prudential values. He lists these values under the following categories: “(1) accomplishment (the sort of achievement that gives life point and weight), (2) the components of a characteristically human existence (autonomy, liberty, and minimum material provision), (3) understanding, (4) enjoyment, and (5) deep personal relations” (Qizilbash 1996, 155; Griffin 1993, 52). Usually, people share these values, though not all of them are equally important for all persons. It may be the case that something good for one person can be bad for someone else. The important thing is that if something is suitable for a particular person, according to Kraut (2009) it fosters a flourishing of the person. It is worth noticing that even this richer view of prudential values (as compared with the previous one which defines values in terms of preferences) can conflict with moral obligations. It may be the case that taking care of other people’s welfare, that is being altruistic, will require a sacrifice of some part of the agent’s well-being (e.g. if I devote some of my time to help other people at the cost of not realizing the prudential value of enjoyment, I sacrifice some of my prudential well-being for the sake of moral values). Now, on the exclusive account of the normative well-being, such sacrifice always amounts to the diminution of well-being. This approach can be more precisely stated in the following way:

The life of an agent S goes well if and only if (a) S’s preference set contains a sufficiently large number of prudential preferences (i.e. preferences expressive of his attachment to prudential goods/values); (b) S chooses prudential goods in many decisional situations; (c) in the case of conflict between prudential values and moral values the agent always gives priority to the former.

As we have already mentioned, the normative force of this account of well-being rests on its reference to prudential values which are not purely subjective but depend on the perception of what is good for a human being. It is debatable whether this is an agent-neutral or agent-relative normativity; if the former, every person has a reason to promote or at least to not undermine other people’s welfare; if the latter, a person has a reason to support only her own well-being. But we shall analyse this problem further. We shall focus instead on a different question, namely: whether (as it is assumed in the exclusive approach) well-being can indeed be achieved by unconstrained (by moral values/obligations) pursuit of prudential values. We shall argue that it cannot.

11.3.2 The Inclusive Approach: Well-being as Constrained Pursuit of Prudential Values

Let us recall that the exclusive approach to the normative account of well-being resolves the two main problems of the non-normative account. First, it is non-tautological, which means that the agent’s action cannot always be (ex-post) interpreted as contributing to her own well-being. It is true that this problem has also been resolved within the second version of the non-normative account – but in an essentially different way: by imposing certain formal requirements on the agent’s preferences and assuming that they are known prior to making a choice, and not (as in the exclusive approach) by introducing certain substantive requirements with regard to the content of the agent’s preferences. Resolving this problem by recourse to the exclusive approach is much more effective: it is by far easier to state that an agent failed to reach the state of well-being if the notion of well-being is defined in a more restrictive manner – by allowing not only formal but also substantive requirements. But this methodological advantage, as one may call it, is less important than the second one. The basic problem of the non-normative account is that it seems to be an incorrect explication of the concept of well-being, for the concept, on its ordinary usage (though not on its usage that is dominant in economics!), has a normative dimension. Moreover, this dimension cannot be reduced to purely formal constraints imposed on the agent’s preferences. The exclusive approach to the normative account undoubtedly does somejustice to this dimension. It, therefore, also resolves (at least to some extent) the second problem. But the question arises whether it does it fulljustice, i.e., whether it does not present well-being in an overly reductionist manner. Let us deal with this question at somewhat greater length. It will lead us to a richer account of well-being, one that makes some reference to moral values.

The exclusive account assumes (correctly, in our view), that the essential (in a causal or constitutive sense) components of well-being are prudential values. If the agent does not pursue them, or if she pursues them unsuccessfully, she cannot be said to have achieved the state of well-being. This claim seems to be true in the empirical sense (prudential values do seem to be the basic source of the positive subjective state, which we tend to call ‘well-being’). But in addition to this plausible claim, the exclusive account also includes a highly controversial one: that an agent who wants to achieve well-being should always give priority to prudential values in the case of their conflict with the moral ones. It is important to understand this (controversial) claim properly: it does not say that a prudential agent can never act morally. If it did, it would be evidently false because the demands of prudence are often convergent with those of morality (that “honesty is always the best policy” is, regrettably, false, but it is for sure true that “honesty is often the best policy”). What it does say is that prudence and morality may give rise to mutually inconsistent claims and that, if we want to achieve well-being, we should always sacrifice the demands of morality. This claim is very difficult to evaluate. It is not even clear what method of evaluation one would need to assume. Whether the method should be conceptual (one would then have to examine perhaps by ‘questionnaire’ methods of experimental philosophy, whether the concept of well-being, as it is commonly used, implies that absolute priority of prudential values over moral ones), or empirical (psychological research examining which of the two types of agents – those never sacrificing prudential values for the sake of the moral ones or those sacrificing them at least occasionally – achieve a higher level of well-being would be needed). Even if the proper method were chosen, it would be naïve to expect that its results would be unequivocal. Their interpretation would, therefore, be difficult. But there seems to be a way out of this quandary. Instead of investigating into how people understand the concept of well-being or examining what psychological research says about the relations between various axiological rankings and the level of well-being, we can make recourse to purely normative considerations and ask whether a conception of well-being which implies the absolute priority of prudence over morality is normatively attractive. It might seem that the resolution of this problem is a matter of taste but, arguably, this is not so; there appears to be a simple and plausible test of a normative attractiveness of a (normative) conception of well-being, namely: whether we would be ready to defend it publicly, to present it openly to other people, or, more pertinently, to treat it as a central – legitimate and attractive – economic concept. One can safely assume that most of ‘us’ (including economists) would be rather embarrassed to admit publicly that their conception of well-being allows for pursuit of moral values only if it does not amount to the sacrifice of the prudential ones. In other words, if economics is not a ‘dismal science’, it cannot assume an exclusive approach to the normative account of well-being. It must go (and, arguably, it does go) beyond it.

But what an inclusive approach to the normative account might look like? It seems that one can distinguish its two main varieties. The first one assumes that:

The life of an agent S goes well if and only if (a) S’s preference set contains a sufficiently large number of prudential preferences (i.e., preferences expressive of his attachment to prudential goods/values); (b) S chooses prudential goods in many decisional situations; (c1) in the case of conflict between prudential preferences and moral values, the agent makes a reasoned choice between them on a case by case basis (i.e., prior to the decisional situation, he does not give priority to any of them).

The second one, in turn, assumes that:

The life of an agent S goes well if and only if (a) S’s preference set contains a sufficiently large number of prudential preferences (i.e. preferences expressive of his attachment to prudential goods/values); (b) S chooses prudential goods in many decisional situations; (c2) in the case of conflict between prudential preferences and moral values, the agent always give priority to moral preferences.

Accordingly, the first one treats moral values as important considerations which cannot be discounted while pursuing prudential values, but not as absolute constraints (only as prima facie constraints), whereas the second one treats them as ‘trumps’ which always win over prudential values, that is as absolute constraints which set impassable limits to pursuing prudential values. We do not intend to decide which of these two varieties of the inclusive approach is the open one; we leave it as an open question. But it is our conviction that any of them is more plausible than either the non-normative ones or the exclusive approach to the normative account of well-being.

11.4 Concluding Thoughts

We have presented several accounts of well-being, starting from its two non-normative forms (which we criticised above all for their lack of normative dimension), and then passing to its normative accounts: unconstrained prudential and constrained prudential. We have argued that the constrained prudential account is most plausible. One may ask, however, why we have stopped here, that is, why we have not proposed another account, which would locate moral values (rather than prudential ones) in the centre and treat prudential values only as prima facie constraints and/or as playing only a subsidiary role in the achievement of well-being. The answer is twofold. First, the general concept of well-being which we endeavoured to explicate or build is subjective making no recourse – unlike the objective one (e.g. Aristotle’s) – to any strong metaphysical assumptions about what it means to be a full/perfect human being.Footnote 1 Though, clearly, the conception which we defended – the constrained prudential one – contains also two (modest) objective components: (a) it assumes that the overwhelming majority of human beings cannot achieve subjective well-being, that is, feel satisfied with their life, if they do not realize prudential values, but (b) constrained in some way by moral values. The objective component (b) is all the more prominent since our argumentation for its introduction was primarily normative; we did not assume, though we find it plausible, that unjust people cannot be truly happy/satisfied with their life. Second, we have intended to compare only those conceptions of well-being which can be accommodated within economics – with its focus on the individual pursuit of various goals, including ‘worldly’/‘material’ ones (social position, economic success, etc.), the subjective satisfaction with their attainment, and with its rejection of any stronger metaphysical assumptions. By contrast, it is characteristic for the classical (objective) conceptions of well-being (e.g., Aristotle’s, and especially that of the Stoics) that they assert that human beings can achieve well-being even in the abject economic conditions. The sublime detachment of this kind of well-being is admirable but is not what economists understand by this term.

Notes

- 1.

See, e.g., Sumner (1998).

References

Bentham, J. 1907. An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation: Library of economics and liberty. https://www.econlib.org/library/Bentham/bnthPML.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Broom, J. 1999. Ethics out of economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Griffin, J. 1993. Against the taste model. In Interpersonal comparisons of well-being, ed. J. Elster and J. Roemer, 45–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harsanyi, J. 1977. Morality and the theory of rational behavior. Social Research 44: 623–656.

Hausman, D. 2011. Preference, value, choice, and welfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kraut, R. 2009. What is good, and why. The ethics of well-being. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pigou, A.C. 1932. The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan.

Qizilbash, M. 1996. Capabilities, well-being and human development: A survey. The Journal of Development Studies 33: 143–162.

Schick, F. 1986. Dutch bookies and money pumps. The Journal of Philosophy 83: 112–119.

Sen, A. 1977. Rational fools: A critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philosophy & Public Affairs 6: 317–344.

———. 1980. Plural utility. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series 81: 193–215.

———. 1986. Prediction and economic theory. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 407: 3–23.

———. 1988. On ethics and economics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Sumner, L.W. 1998. Is virtue its own reward? Social Philosophy & Policy 15 (1): 18–36.

Varian, H. 2010. Intermediate microeconomics. A modern approach. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kwarciński, T., Załuski, W. (2021). Beyond Mere Utility-Maximisation. Towards an Axiologically Enriched Account of Well-being. In: Róna, P., Zsolnai, L., Wincewicz-Price, A. (eds) Words, Objects and Events in Economics. Virtues and Economics, vol 6. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52673-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52673-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-52672-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-52673-3

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)