Abstract

The Constitution of Kenya gives the government an oversight role in setting and enforcing quality standards for health services. While the Kenyan Ministry of Health has numerous policy documents and legal frameworks to enforce quality care, its capacity to perform inspection visits and enforce licensing requirements has been limited. To help support the institutionalization of a regulatory framework to promote quality health care, PharmAccess, a Dutch nongovernmental organization, launched a strategic collaboration with the Kenya Ministry of Health and the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) to embed accredited clinical and business quality standards into a national quality assurance system and to introduce the standards and quality improvement methodology into the contracting process of health-care providers by the NHIF. This case focuses on the introduction of medical and business quality standards at St. Patrick Health Care Center, a private provider in Nairobi. The program has helped the facility to attract financial loans to improve the scale, scope, and quality of their services and to generate extra income by securing a contract with the NHIF to provide health-care services to NHIF members in addition to other private insurers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Accreditation

- Kenya

- National Hospital Insurance Fund

- Quality improvement plan

- Quality standards

- Stepwise certification

Background and Regulatory Framework

The Constitution of Kenya gives the government the responsibility for ensuring the realization of the right to health—meaning equitable, affordable and quality health services for all citizens—as well as an oversight role in setting and enforcing quality standards for health services. Kenya has numerous policy documents and legal frameworks to support the national goal of health for all.Footnote 1 Although quality of health services is implied in all these documents, as of 2019, they are still being reviewed to clarify how these policies should be implemented and are therefore not fully operationalized. Despite national and county governments motivated to make a difference, as in many low- and middle-income countries, ensuring quality health care in Kenya remains a major challenge. The capacity of government to perform inspection visits and enforce licensing requirements has been limited, and inspectors are often faced with the risk of having to close down facilities that are perhaps the only possibility for patients to receive care in a region. Importantly, the same enforcement mechanisms do not always apply to both public and private facilities, creating disparities in the health sector.

With weak enforcement of a regulatory framework to measure and enforce adherence to quality standards, patients and funders of health care face uncertainty regarding the availability and quality of services in the health sector (Ruelas et al. 2012; Das and Gertler 2007; Das and Hammer 2014; Øvretveit 2004; Peabody et al. 2006; Smits et al. 2014; Mate et al. 2013). This uncertainty hampers investments in the health sector, since patients are not willing to prepay for health care through risk pooling. Low utilization of health services and a lack of reliable income refrains health-care providers from investing in the quality, scope, and scale of their services. This results in a vicious cycle of poor supply of and poor demand for health care.

Transparency about the quality of care and care delivery is crucial to break this vicious cycle. Patients need to know what quality of care they can expect at a certain facility. Funders need data on quality and risk to assess the medical, financial, and accountability risks when considering long-term investments. Insurance companies need data to determine which providers their customers can use and to assure value for money. At a policy level, data on quality and risks assist governments and donors in their choices about how to best allocate their scarce resources to improve quality and lay the groundwork for a regulatory framework (Scott and Jha 2014). Data collected during facility inspections on size, scope, and quality of health-care services can support all these objectives across the sector and stakeholders.

To help create transparency of care provision and lay the basis for institutionalizing a regulatory framework, in June 2013, PharmAccess, a Dutch nongovernmental organization (NGO) dedicated to improving access to better health care in Africa, launched a formal, strategic collaboration with the Kenya Ministry of Health, the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) and the Health in Africa Initiative of the International Finance Corporation. The key objectives of the collaboration are to embed accreditedFootnote 2 clinical and business quality standards into a national quality assurance system and to introduce the standards and quality improvement methodology into the contracting process of health-care providers by the NHIF. Use of uniform quality standards will create transparency on the size, scope, and quality of care of health-care facilities in Kenya and allow for benchmarking between facilities and regions. The results could be used to guide improvement within a facility but also for decision-making on NHIF insurance contracting, pay for performance, reimbursement based on quality of care, health system management, policy development, and access to credit.

PharmAccess’ approach for this initiative has focused on public and private health-care facilities at the “bottom of the pyramid,” such as dispensaries and health centers, which are the primary health-care distribution channel in low-income settings and often struggle with patient safety and quality demands. The program offers a stepwise certification process complemented by technical assistance whereby a facility pursues explicit levels of quality based on explicit criteria by implementing improvement plans to work toward the next level. Where financing for improvement is needed, facilities, through the Medical Credit Fund, can get access to affordable loans with local banks (PharmAccess Group). The Medical Credit Fund facilitates loans to clinics to stimulate growth and encourage new ways of financing health care.

Each quality level is recognized by a formal certificate. This creates an improvement path that offers positive incentives for health-care providers to enhance quality and ultimately qualify for accreditation when the highest level has been achieved. Whereas the latter objective might remain out of reach for many providers for some time to come, a pathway to work toward that objective can boost client, investor, and regulator confidence in the motivation and capacity of health-care providers to steadily enhance their performance.

Designing and Organizing the Improvement Effort

Universal Health Coverage, one of the Sustainable Development Goals, has been adopted as an important national priority in the Constitution of Kenya in 2010 and part of the “Big Four” agenda of President Kenyatta. One of the drivers for Universal Health Coverage in Kenya is the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF). The NHIF is a publicly owned insurance corporation that provides insurance to adults in Kenya working in the formal sector but also offers the so-called SupaCover for the informal sector. For the NHIF to expand its insurance packages to all Kenyans, improving and ensuring the quality of care delivered by hospitals and clinics contracted by NHIF are critical. In order to expand coverage for its members, the NHIF developed and implemented an accreditation system for contracting providers. The management of NHIF, however, wished to have a system more aligned with international accreditation standards used by other countries, such as South Africa, Australia, the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands, based on International Society for Quality in Health Care-accredited clinical standards and evaluation processes. The system should also be part of a continuous improvement process for the facility and not just contracting. However, international accreditation standards such as those set by the Joint Commission International—globally considered the gold standard of health-care accreditation—are generally acknowledged as difficult to implement and maintain in settings where resource constraints hamper compliance. Few health-care facilities in low- and middle-income countries can afford the accreditation process, and once achieved, there are not enough incentives for facilities to make the investment worth it. In Kenya, as of 2019, only the Aga Khan Hospital and Gertrude’s Children’s Hospital in Nairobi have achieved Joint Commission International accreditation. For NHIF, therefore, the stepwise approach offered by PharmAccess was a better match as a basis to introduce international standards and yet support facilities to meet those standards by making structured, incremental improvements in quality.

PharmAccess built the capacity of the NHIF for a more structured quality system and to incorporate internationally recognized health-care quality and business standards into the NHIF’s health-care facility contracting structure. For sustainable quality improvement, having the certification methodology embedded within the NHIF and used for contracting provides much-needed financial incentives for providers, as it provides them a regular income through the capitation system for outpatient services and fee-for-service for inpatient services the NHIF uses.

Inception of the Collaboration

The quality improvement (QI) program began with the formation of a Steering Committee—consisting of the senior NHIF managers (the Chief Executive Officer and the Manager for Benefits and Quality Assurance), the Kenya program lead of the Health in Africa Initiative, and PharmAccess leadership—convened to discuss the strategic direction of the engagement and to draft a Memorandum of Understanding that described the overall objectives of the partnership. Against this framework, more detailed operational plans were designed to achieve the agreed objectives. The Steering Committee was also responsible for overseeing the implementation of the operational plans. Progress was discussed during regular meetings.

Drafting and implementing the operational work plan were the responsibility of the Technical Working Group, which organized monthly meetings. These meetings were attended by quality managers and assessors from each organization (NHIF, International Finance Corporation, and PharmAccess) who could steer the process of developing an operational plan and report back to the Steering Committee as well as their own staff when further input was needed. The Technical Working Group addressed capacity building of NHIF quality assessors, planning of the quality assessments, the quality and business standards that would be applied in the assessments, and embedding the assessments in the overall NHIF structure of contracting health-care providers. They developed an annual training schedule, list of training participants, meeting dates, plans for software implementation, and the organizational structure to support standards-based quality assessments and stepwise certification by the NHIF through its regional managers, who were responsible for implementation. The Technical Working Group provided the implementers with practical details about how the implementation of the standards and certification process should take place.

Capacity Building at the National Hospital Insurance Fund

The NHIF, the Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa, and PharmAccess Foundation organized several five-day quality assessor trainings for NHIF Quality Assurance Officers from the 15 NHIF regions. The Quality Assurance Officers, drawn from various medical professions, including clinical officers, nurses, laboratory technologists, and public health officers, would be responsible for doing the actual assessments using the standards. The NHIF selected them based on their performance regarding quality assurance and their motivation and ability to drive quality improvement in each region and champion the process. The selection of the top performers in each region to serve as quality assessors would ensure that there would be adequate buy-in at the regional level. Pre- and post-tests were done to establish participants’ knowledge and understanding of the standards and assessment process prior to and after the training. In addition to presentations and training materials, the participants discussed case studies, conducted a mock survey using the standards at three facilities, and developed a quality improvement plan using the supporting software system.

To become a qualified quality assessor, participants also needed to successfully complete two mentored quality assessments. Experienced assessors from PharmAccess accompanied the trainees to a health facility to evaluate their work during an assessment. This entailed conducting a full assessment in which the experienced assessor and the trainee both gathered data independently and then crosschecked their scores, incorporating peer-to-peer learning. Through discussion and comparison of his or her assessment with that of one of the surveyors, the trainee would identify areas of scoring that were not clear. These topics were then discussed between trainee and mentor, consulting scoring guidelines.

Next, five NHIF regions (Nairobi, Rift Valley, Nyanza, Eastern, and Central) were selected to start rolling out the quality assessments in their area. These regions conduct two assessments per month with the support of PharmAccess staff, resulting in 30 assessments in 3 months. By working together in assessment teams of two people to conduct assessments and review data at the regional level, the regions built internal capacity and became more efficient at conducting assessments and providing quality improvement support. Quality officers from the Ministry of Health joined several of the training sessions and field visits to ensure that they were involved in these activities and that the activities were aligned with national policies.

Improving Care at a Nairobi Health-Care Provider

St. Patrick Health Care Center, located on a commercial road in Nairobi’s densely populated Kayole area, is one of the go-to health-care facilities for the mainly poor and low-income population residing in the area. The facility is owned and managed by a woman who is a trained nurse by profession. The private, for-profit facility has 17 staff members and 26 beds and is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The patients visiting the facility are mostly self-employed in retail activities, handicrafts, or personal services, like barbers and taxi drivers.

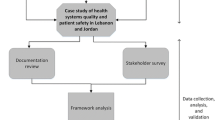

St. Patrick joined the stepwise certification program in early 2012. At the start of the QI program in March 2012, the facility signed a participation agreement and received a one-day, on-site training for the key staff (managing director, matron, and department leaders). This was done to ensure that the team understood the quality and business standards. An external assessment was then conducted by PharmAccess staff, which resulted in the development of a quality improvement plan outlining areas for improvement. The program provided quarterly monitoring and support visits to help St. Patrick’s quality team and follow-up assessments in 2013 and 2016 to evaluate overall improvement. A short overview of the process is depicted in Fig. 7.1.

Assessment Standards, Scoring, and Certification

The health-care quality and business standards included in the quality assessment cover the full range of clinical services and management functions, divided into 13 service elements grouped in four areas:

-

Health-care organization : (1) Management and leadership, (2) human resource management, (3) patient and family rights and access to care, (4) management of information, (5) risk management

-

Patient care: (6) Primary health-care services (Outpatient care), (7) inpatient care

-

Specialized services: (8) Operating theater and anesthetic services, (9) laboratory services, (10) diagnostic imaging services, (11) medication management

-

Ancillary services: (12) Facility management services, (13) support services

Adherence to standards is measured by assessing each service element against a number of scoring criteria, which are measurable elements that define specific requirements. Each criterion is marked as “not compliant,” “partially compliant,” or “fully compliant”; a mark of “not applicable” is given if the service measured by the criterion is not provided at a given facility. PharmAccess experts then review the results and scores and assign a certification level based on a proprietary algorithm. This certificate is awarded to acknowledge the provider’s progress on the quality journey. The program recognizes five levels of improvement, with the highest (Level 5) indicating a provider’s readiness to apply for international accreditation.

The first quality assessment at St. Patrick was conducted in June 2012 to measure the level of quality of health services delivered by the facility and identify priorities for quality improvement. The assessment team, who had all successfully completed the assessor training, included a nurse, a laboratory technician, a pharmaceutical technician, and a business advisor. The assessment exercise took a day to complete. The data were reviewed by PharmAccess reviewers who discussed discrepancies identified, unclear comments, and ambiguous scores in the assessment data with the team leader, who then made the necessary adjustments to improve the quality of the assessment data. The data review and approval process took 2 weeks to complete. After the baseline assessment, St. Patrick Health Care Center achieved Level 2 certification, which indicated that “The facility is starting to operate according to structured processes and procedures, some of which are captured in written guidelines and standard operating procedures. However, health care quality is still likely to fluctuate.”

Initiating the Improvement Process at St. Patrick

An essential part of implementing the improvement process is the creation of a quality team within the facility that includes the facility’s clinical leadership, usually the medical director and department heads, with a team lead among the staff spearheading the implementation process. The quality team lead at St. Patrick was a nurse who had attended various trainings on infection prevention and risk management. Other staff on the newly formed quality team included the human resources manager, sales manager, laboratory in-charge, pharmacy in-charge, nurse in-charge, kitchen supervisor, and support staff team supervisor. This multidisciplinary approach aimed to demonstrate that quality within the facility was every department’s responsibility. Having a quality team is also in line with the national policy in Kenya that requires all facilities to have one. A simple policy and procedure document was drafted and adopted by the team, which outlined management of the team and general expectations of the team, to facilitate its effectiveness.

The health facility received a quality management training by the quality officers of PharmAccess, both in a classroom setting and at their workstations. The team leader presented a draft quality improvement plan (QIP) developed by PharmAccess to the facility’s quality team to discuss the proposed activities and their distribution across the implementation period as well as assigning responsible persons for each activity. The draft QIP was developed based on a proprietary algorithm of PharmAccess that identifies noncompliant areas that are either high risk to patients, to staff, or to the business performance of the provider. During the meeting, inputs and activities suggested by the facility management and staff were incorporated. The team leader made subsequent adjustments and presented the revised QIP to the PharmAccess quality officer for review and approval. The purpose of this process is to ensure both local ownership of the plan and that essential gaps in quality are addressed and that the QIP is ambitious enough.

The team leader then proceeded to share the findings of the approved assessment and the QIP with the entire facility to encourage adoption of all the actions in the QIP. The facility-wide meeting provided an opportunity for all staff to hear the findings of the assessment and discuss the proposed activities as presented in the QIP. Slides highlighting departmental performance drew particular attention. The use of pictures taken during the assessment to show gaps and emphasize good practices resonated well with the staff, causing those present to accept and own the report. The approach that was taken was nonpunitive, to stimulate an open, learning environment.

Each of the members of the quality team then coached the implementation process in their respective departments. Activities varied from the introduction of stock management tools and job descriptions to redesigning the patient flow process (see Table 7.1). Thereafter, the quality team met on a monthly basis to discuss progress on improvement activities in the different departments. The team lead kept the facility manager informed about progress and funding needs. All meeting discussions were documented in the quality team file. As a result of this consultative process, the staff at St. Patrick quickly embraced the quality improvement process.

The facility received technical assistance from PharmAccess quality officers, who visited the facility approximately every quarter to measure the extent to which the quality improvement plan was being implemented. These visits aimed to assist the facility quality team to identify bottlenecks and provided support to find solutions. The facility also had access to an online library with guidelines, checklists, protocols, and other materials developed by PharmAccess to help meet the program’s quality standards.

Addressing quality gaps is not only about improving structures and procedures; financial investments in equipment and infrastructure are needed. The program has helped providers to unlock investments as they help the owners think about their work as a business. Shortly after joining the program, St. Patrick obtained a loan, as well as business training, through the PharmAccess Medical Credit Fund. With a Kenya shilling (Ksh) 500,000 (USD 5000) loan, they purchased computers, installed a computerized management system, internal phone lines, and a closed-circuit television system (a TV system primarily used for surveillance and security purposes). They also invested in having an external auditor check their financial accounts and made minor infrastructural improvements. The business training helped the facility to prepare for a larger loan qualification, draft a business plan, and prioritize its investments.

The initial assessment report was an eye-opener for them. “We were not running the facility in the right way,” the owner explained. “We had no administration office, no systems. We used to work from our pockets, writing on patient cards, and counting the shillings at the end of the day. SafeCare helped us to establish our gaps and set in motion interventions to improve ourselves. Now, our record keeping is accurate, and we have audited accounts and a digital client history that can be accessed at any time. The system has also helped minimize fraud and track the expiration dates of drugs in our pharmacy.”

The experience they gained in qualifying for their first loan through the Medical Credit Fund was instrumental in building a financially sound organization. Through the training and on-site support, they learned how to draft a business plan and which documents to deliver to the bank. Financial records were now neatly in place. They repaid their first loan within 6 months. Their track record and improved financial management enabled them to secure a Ksh. five million (USD 50,000) loan from a bank to invest in their laboratory and expand the facility.

“It was difficult sometimes in the beginning because SafeCare requires a new way of thinking, both for us and for our staff,” the owner says. “It’s about accountability, transparency, and establishing procedures – in all departments, from the cleaners to the medical personnel. But now that our staff has seen what the program can do, they are fully on board and committed to continue to improve our quality.”

For instance, in the beginning, St. Patrick’s quality team felt that improving the facility’s documentation required additional work for which they did not have time. After some initial encouragement, they realized the benefits of their time investments; fewer insurance claims (both NHIF and commercial) were rejected, thanks to the improved documentation. The facility also implemented some very visible, patient-focused improvements; for example, the renovation of the waiting room, previously a crowded room that was the cause of complaints. The redesign process was easy to implement; it involved various departments and was considered “low hanging fruit,” as it did not involve complex processes, training sessions, or issues that could be considered political, such as nonperforming staff. The renovation not only resulted in better patient flow but also elicited positive responses and compliments from the patients, which encouraged the staff members to continue on their improvement journey and experience pride in the results. Table 7.1 provides illustrative examples of improvement activities instigated at St. Patrick that contributed to overall better performance of the facility and compliance with the certification standards.

Technical Support for Improvement

During the implementation process, one quality assurance officer from PharmAccess visited St. Patrick quarterly to monitor progress, identify bottlenecks, and support the quality team in finding appropriate solutions. The NHIF quality assurance manager accompanied the PharmAccess officer on two visits but had too many other responsibilities to provide regular support to specific facilities. St. Patrick Health Care Center was also encouraged to call the PharmAccess quality officer anytime if they needed specific assistance with any of their improvement activities.

During one quality team meeting, facility staff expressed the need to improve on the level of waste management and infection control in the facility. The main challenges in the facility included lack of color-coded bags for waste bins, lack of proper waste segregation at the point of generation, lack of proper storage of generated waste in the facility, and lack of a documented policy to guide staff on waste management and infection prevention. In addition, the facility was struggling with providing clean running water, soap, and hand-drying towels in key areas, such as the laboratory.

The quality team lead prepared a short presentation on waste management practices in the facility, using pictures and demonstrations (e.g., on proper hand washing techniques and waste management). This was then followed up by drafting of a quick plan of action that detailed what was required for improvement (e.g., procurement of coded bins, procurement of hand-drying towels, documentation of policies and procedures) and indicated the respective staff assigned to complete each activity, the budget required (if any), and finally, the period of completion for each specified activity.

Results

St. Patrick Health Care Center began the improvement work at Level 2 certification (based on their baseline assessment scores), but achieved Level 3 certification within 6 months through changes implemented to improve quality of care. St. Patrick’s significant progress in implementing their QIP qualified the facility for a third follow-up quality assessment in November 2016.

After the third assessment, the facility achieved a Level 4 certificate, making it one of the highest-performing facilities in terms of quality in Kenya. Level 4 certification means that “The facility is regularly monitoring the implementation of treatment guidelines and standard operating procedures through internal record reviews and (clinical) audits. Most high-risk processes and procedures are controlled.” After the third assessment, a new QIP was prepared to guide the facility in continuing to improve quality to advance to an even higher certification level.

Figure 7.2 shows the improvement in assessment scores achieved by St. Patrick over the three assessments. While the facility demonstrated an increase in most service elements, as is common with improvement trajectories, scores fluctuated somewhat with an overall positive trend. As St. Patrick does not have surgery services, this service element was not scored.

The next step is installing an operating theater. The facility is eager to continue improving quality of care to reach Level 5. “SafeCare needs a lot of commitment, but you feel like you’re in another world. It makes you feel like a professional,” said the owner.

Achieving National Hospital Insurance Fund Contracting

During previous inspections by the NHIF of St. Patrick, the facility was unsure what was expected of them and what were the standards against which they were evaluated; as a result, St. Patrick failed to meet the criteria for NHIF accreditation . There was no manual or checklist used by the NHIF assessor, and St. Patrick was not offered advice on how to improve on shortcomings that prevented their NHIF accreditation. After the introduction of the program, the facility received a clear overview of what they were evaluated against and how to introduce the necessary changes to adhere to these standards. As a result, St. Patrick became NHIF-accredited in November 2012, ensuring a larger client base and income flow. Patient visits have risen, and the facility has also managed to contract with corporate clients and private medical insurance companies. In turn, the more regular income and client base from serving insured patients have been key to financing and sustaining the quality improvement work, apart from PharmAccess technical support.

Scaling Up and Sustaining the Certification Program

Introducing international standards, stepwise certification , and a transparent rating and improvement program to health-care providers in Kenya has proven to be a successful approach toward sustainable quality assurance. The combination of using this approach in conjunction with NHIF contracting and embedding it in the framework of the national quality policy of the Ministry of Health offers both the incentive and the enforcement mechanism to encourage providers to participate in quality improvement initiatives. The case study of St. Patrick Health Care Center gives insights into the actual activities that are needed within a facility to meet adherence to the standards. These activities require both committed management and committed staff. In addition, financial means/access to credit, such as through the Medical Credit Fund, are also helpful.

Data on the overall effectiveness of the program in Kenya show that 84% of the participating facilities have improved their quality scores between the initial and second assessments, suggesting that the stepwise approach is, for many facilities, an efficient and effective approach.

In 2017 and onward, quality system coverage continues scaling up under NHIF ownership. Scaling up has also come with challenges and exposed gaps in the system. The NHIF Senior Manager for Benefits and Quality Assurance at the national office states, “The national office led the discussions for the strategic partnership and involved the regional managers through internal strategic meetings. These discussions were held in the wider context of the NHIF quality assurance program and the proper integration in the NHIF annual work plans implemented by the regions. Some of the challenges the regional mid-level Claims and Quality Managers face are competing priorities within the NHIF, compounded by staff who perform both claims and quality. These issues have influenced our decision to start with a few regions with selected staff to get results and learn lessons that can be used to scale up.”

A key learning during implementation of the program is that much more engagement with facilities on issues of quality is needed. The providers need supportive supervision and guidance, rather than just inspections and enforcement. Facilities which have been contracted by the NHIF recently need to be regularly visited because they need to be taken through NHIF processes as well as be guided on how to carry out their quality improvement meetings. It is recognized that for the NHIF, this need can compete with other needs and demands, and policy discussions should be encouraged to determine whether in the future this role should remain with NHIF, or whether an independent quality improvement and assurance institute should take up this role.

In the beginning, facilities find the quality improvement process very demanding, but as they go along, they find it easier to work with the process. Most of the facilities which have fully embraced the quality improvement process find a lot of benefit in it, since they are able to plan and budget well for the facility, monitor goods and supplies, have good bookkeeping allowing them to track their finances, and have a structured patient management process which improves client satisfaction. Another key motivator for facilities is that the NHIF can pay out their claims much faster as a result of improved bookkeeping and patient documentation. As the NHIF Regional Benefits and Quality Assurance Officer states, “Our regional Claims and Quality Assurance Managers appreciate the stepwise accreditation standards and quality improvement methodology, since it makes their work easier, and they receive fewer complaints. Before the introduction of the stepwise accreditation standards , our work consisted of conducting inspections to see whether facilities complied with our quality and financial regulations. At the time, the NHIF concentrated more on fraud management than on quality issues.” He also advises that in order to introduce a quality program in an institution like the NHIF, it is important to study the organization well and understand its internal structures and how it relates externally. Such programs should always aim to build the capacity to develop homegrown strategies, and the process should be long term. Quality improvement programs must be institutionalized and driven by the facilities.

Reflection

A main barrier to large-scale adoption of any quality program is the relatively high cost of quality assurance, currently funded primarily by donors. First, the focus should be on how to build sufficient local capacity to ensure local ownership and low costs; next, on how to embed the methodology within the health-care system to provide both enforcement and incentive strategies that guide facilities toward improvement.

“Although quality improvement is seen as important, more work needs to be done to convince facility owners to bear some of these costs themselves,” adds the PharmAccess Country Director for Kenya. One way of promoting co-financing is to strengthen for health facilities the linkage between achieving a higher accreditation certificate and benefitting both financially (more patients and better contracts) as well as socially (awards and recognition among peers). For example, facilities in the neighborhood of St. Patrick have also asked to be in the program, and the owner of St. Patrick has been invited to talk about their experience and results at conferences and stakeholder meetings.

By requiring a minimum level (for example, Level 2) to participate in NHIF contracting and rewarding facilities that continuously show improvement with higher medical pay-outs, both enforcement and incentive mechanisms can be in place to sustain improvement. NHIF, PharmAccess, and the International Finance Corporation continue discussing possibilities of linking quality to the reimbursement of claims. A proposal has been made in the Health Financing Bill of Kenya to link quality to financing.

“It takes time for quality to improve, and for those improvements to be sustained,” says a policy officer at the Health in Africa Initiative of the International Finance Corporation. “It involves behavioral change in addition to increased motivation, knowledge, resources, and organizational management. Long-term strategies need to be deployed for quality improvement, designed to go beyond the project life cycle. It should be ensured so that the results achieved are not lost. Linking quality improvement to pay-for-performance mechanisms motivates the health facilities to invest in improvement and sustain this work.”

Establishment of an independent accreditation body has now been endorsed in the health improvement policy, the draft health bill, and in the health financing strategy (currently under development). With policy implementation and regulation, quality improvement can be further encouraged in both the private and public sectors. The standards presented in this case study have been recognized as a key methodology for accreditation, and with franchises, private clinics, and the NHIF adopting parts of the methodology, a firm basis has been laid for institutionalization.

Author’s Reflection

To strengthen health systems in low- and middle-income countries, it is important that national governments step up their role as supervisor. They need to integrate licensing, transparent quality standards and benchmarks, and accreditation into health policies and to enforce compliance. Better data will help governments to allocate their scarce resources more efficiently to invest in quality improvement. Improvements in health-care quality can yield numerous benefits to populations, bringing increased access to health services that are safe, effective, and patient-centered.

The adoption and incorporation of the SafeCare standards by the NHIF and various other health system actors in Kenya build a platform to support increased trust and transparency in the system. The SafeCare methodology is embedded in a health-financing model that aligns incentives and gives regulators and insurers leverage to ensure sufficient quality in the health-care services that are procured. The partners in this program have developed and implemented a set of quality standards and a scalable assessment and scoring methodology that assist in laying the foundation for a sustainable, Kenya-owned quality monitoring system.

–Nicole Spieker, Director Quality, PharmAccess Foundation, August 2017

Notes

- 1.

Including the Kenya Health Policy 2012–2030, the Kenya Vision 2030, the Kenya Quality Model for Health, the draft Health Bill 2012, the draft health financing strategy, and the Kenya National Health Sector Strategic Plan III for 2013–17.

- 2.

The PharmAccess health-care quality standards program, known as SafeCare , has been accredited by the International Society for Quality in Health Care. SafeCare (http://www.safe-care.org/index.php?page=safecare-standards) is a collaboration between PharmAccess and the accreditation bodies Joint Commission International (United States) and the Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa (South Africa) designed to apply International Society for Quality in Health Care-recognized clinical standards that are realistic for resource-restricted settings. SafeCare dissects the improvement process of health-care providers in surveyable, measurable steps (Johnson et al. 2016).

References

Das J, Gertler PJ (2007) Variations in practice quality in five low-income countries: a conceptual overview. Health Aff (Millwood) 26(3):w296–w309

Das J, Hammer J (2014) Quality of primary care in low-income countries: facts and economics. Annu Rev Econ 1(1):1–41

Johnson MC, Schellekens O, Stewart J, van Ostenberg P, de Wit TR, Spieker N (2016) SafeCare: an innovative approach for improving quality through standards, benchmarking, and improvement in low- and middle-income countries. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 42(8):350–371

Mate KS, Sifrim ZK, Chalkidou K, Cluzeau F, Cutler D, Kimball M et al (2013) Improving health system quality in low- and middle-income countries that are expanding health coverage: a framework for insurance. Int J Qual Health Care 25(5):497–504

Øvretveit J (2004) Formulating a health quality improvement strategy for a developing country. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 17(7):368–376

Peabody JW, Taguiwalo MM, Robalino DA, Frenk J (2006) Chapter 70. Improving the quality of care in developing countries. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries. Second Edition. Washington, DC: The World Bank and Oxford University Press

PharmAccess Group. Medical Credit Fund Africa. https://www.medicalcreditfund.org/

Ruelas E, Gómez-Dantés O, Leatherman S, Fortune T, Gay-Molina JG (2012) Strengthening the quality agenda in health care in low- and middle-income countries: questions to consider. Int J Qual Health Care 24(6):553–557

Scott KW, Jha AK (2014) Putting quality on the global agenda. N Engl J Med 371:3–5

Smits H, Supachutikul A, Mate KS (2014) Hospital accreditation: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Glob Health 10(1):65

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the following individuals for their contributions to the SafeCare application in Kenya:

Millicent Olulo, Regional Director for Advocacy and Partnerships, Former Country Director, Kenya, PharmAccess

Kasmil Masheti, Quality Manager, PharmAccess

Mary Njoki, Quality Manager, PharmAccess

Simeon Kirgotty, Former Chief Executive Officer, National Hospital Insurance Fund

Joseph Githinji, Former Manager, National Hospital Insurance Fund

Frank Wafula, Policy Officer, International Finance Corporation

Njeri Mwaura, Policy Officer, International Finance Corporation

Ann Maira, owner, St. Patrick Health Care Center

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 University Research Co., LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Spieker, N. (2020). The Business Case for Quality in Health Care. In: Marquez, L. (eds) Improving Health Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43112-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43112-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-43111-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-43112-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)