Abstract

This case describes how QI methods were applied in an emergency response context to improve health-care delivery during an infectious disease outbreak – the Zika epidemic that affected Honduras and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean beginning in 2016. It describes the national-level efforts of both the Ministry of Health and Social Security Institute to strengthen health services in the context of a novel and rapidly spreading epidemic and shows the process of improving care at the facility level, through the experience of the Catacamas Polyclinic in the Olancho Region of Honduras. The case illustrates how the efforts of facility-level QI teams were supported by and coordinated with national-level efforts to develop and promulgate updated standards of care and train health workers in their application. Ministry of Health support for the QI activities included coaching support by central and regional-level QI coaches, support for monitoring of performance indicators, and facilitation of peer-to-peer learning among QI teams to scale up learning about how to improve Zika-related care.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Collaborative improvement

- Counseling

- Family planning

- Honduras

- Peer-to-peer learning

- Performance monitoring

- Quality of care

- Zika

Background

In early 2015, an outbreak of the Zika virus emerged in Brazil; within a year, the virus had spread to 21 other countries in the Americas. As the magnitude of the epidemic unfolded, new and troubling evidence emerged about an uptick in birth defects in Zika-affected regions and their potential link to this virus, causing the World Health Organization to declare Zika a public health emergency of international concern, defined as “an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response” (World Health Organization).

The Zika virus was discovered in 1947 in the Zika forest of Uganda. It caused an epidemic in Micronesia in 2007 that spread to several countries in Oceania before reaching the Americas in 2014. The Zika virus spreads among people mainly through the bite of an infected mosquito – the same type of mosquito (Aedes aegypti) that transmits Chikungunya and dengue. In addition, the virus can be transmitted between people through sexual intercourse and from a pregnant woman to her baby during pregnancy or at birth. A Zika virus infection during pregnancy can cause microcephaly and other serious brain defects in the developing baby. In addition, there are a host of other possible health and development issues that are being observed in infants and children who were exposed to Zika in utero that continue to be under study.

By 2017, local transmission of the Zika virus had been detected in 148 countries in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. Thirty-one countries or territories had reported cases of microcephaly and other central nervous system malformations, possibly associated with Zika virus infection or that suggest a congenital infection, and 23 of them have reported an increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) and/or confirmation of Zika virus infection in GBS cases through laboratory tests. Thirteen countries or territories have reported incidence of sexual transmission of Zika.

In Honduras, 32,142 suspected Zika cases had been reported by 2016. Out of these cases, 665 were among pregnant women, 46% of whom were confirmed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test to have had a Zika virus infection during pregnancy. By late 2016, 134 cases of microcephaly were reported; of these, evidence of the mother having had a Zika virus infection during pregnancy was confirmed by a laboratory test (RT-PCR or serology) in only four cases. The highest incidence of Zika virus infections was recorded in five departments (and cities): Francisco Morazán (Tegucigalpa), Cortes (San Pedro Sula, Choloma, Villanueva), Yoro (El Progreso), Olancho (Juticalpa), and El Paraíso (Danlí).

The Zika Response

As the epidemic unfolded, national governments across Latin America and the Caribbean and the international community quickly mobilized resources to respond to the threat. In Honduras, the national authorities implemented a multisectoral response, organized by the President of the Republic, which included the participation of the Ministries of Health, Education, and Social Inclusion as well as international health organizations like the Pan American Health Organization, USAID, and others. USAID provided technical and financial support through implementing organizations for a range of Zika response efforts, including vector control (ZAP Project), communication campaigns (UNICEF and Breakthrough Action), service delivery (USAID ASSIST Project), and community mobilization (PASMO, Global communities, Project CAZ). A coordination team was formed within the Honduran Ministry of Health (MOH), with the participation of technical staff from relevant MOH units (Health Surveillance, Service Networks Directorate, Primary and Secondary Care Departments, General Directorate of Standardization, among others). This group was named the Zika Strategic Command, and it became the focal point of coordination for all Zika activities in Honduras.

USAID requested in 2016 that one of its projects with decades of experience applying improvement methods to health care begin implementing activities in Latin America and the Caribbean to strengthen the ability of the health systems to respond to the Zika epidemic. Specifically, the project sought to integrate Zika care within family planning, prenatal, and newborn services to improve the capacity of the health system to deliver consistent, evidence-based, respectful, people-centered, high-quality Zika-related care to women of reproductive age, pregnant women, and mothers of newborns affected by Zika and their families. A key goal was to improve client and provider knowledge about Zika and its consequences, particularly for newborns, and about how to prevent Zika virus infection. To meet this need, in Honduras, the project coordinated with the two largest health service providers – the Ministry of Health and the Honduran Institute of Social Security (IHSS, for its acronym in Spanish) – to start an initiative to improve the quality of health services in both organizations.

Designing the Improvement Effort at the National Level

Overview of the Honduran Health System

The MOH is the largest provider of health services in Honduras, covering around 60% of the population. The IHSS serves the working population of the country that has health insurance, covering around 12% of the population (Carmenate-Milián et al. 2017). Within the MOH, there are two levels of care. Primary care is provided by teams in the community or health facilities that provide outpatient care with basic services in obstetrics, pediatrics, internal medicine, and, in some facilities, labor and delivery. Secondary care comprises inpatient services and specialized care provided through different types of hospitals.

The Zika Strategic Command (ZSC) drew on the technical expertise and experience of a multidisciplinary team that was responsible for coordinating health promotion and Zika prevention activities at the community, ambulatory, and hospital levels. The USAID ASSIST Project gave technical assistance to the ZSC to initiate its plan. One of ASSIST’s first activities with the ZSC was to decide on appropriate indicators to conduct a baseline assessment of Zika care in the health facilities within the high-incidence departments. Given the recent emergence of Zika in the Americas, another important activity early in the response was to draft national guidelines for comprehensive management of patients with a suspected or confirmed Zika virus infection during preconception, pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum stages and for care of newborns affected by congenital syndrome associated with Zika virus (CSaZ).

At IHSS, the Medical Directorate created a technical team to implement activities within their institution, which included the participation of Epidemiological Surveillance and the Quality Management Unit and the coordination of the North-Western Region of the country, where more cases were concentrated. This technical team worked closely with the ZSC.

Site Selection

For implementation of Zika care improvement activities in Honduras, the USAID-funded project coordinated with the national-level Zika Strategic Command to select 42 health facilities for the initial improvement work; 12 of these facilities were hospitals (10 MOH and two IHSS), and the rest were primary care facilities (20 MOH and 10 IHSS). These facilities were selected because they had the highest incidence of suspected Zika cases. The 42 facilities were located in Atlántida, Choluteca, Cortes, El Paraíso, Olancho, Santa Barbara, and Yoro departments and the metropolitan regions of Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula. Within each region, a team of technical advisors from the MOH, IHSS, and the USAID-funded technical assistance project coordinated Zika service strengthening activities with the Health Region Coordinating Team and the managers of the selected primary care health facilities and hospitals.

Baseline Assessment

One of the strategic objectives proposed by USAID-funded technical assistance project was the integration of Zika counseling in the services provided to women of reproductive age, mothers, and families to educate clients on Zika risks and complications and to teach and encourage clients to take personal protective measures and other actions to prevent Zika. As a first step, the MOH, IHSS, and USAID-funded project conducted a baseline assessment in the 42 priority facilities to understand what health service clients knew about the Zika virus and how to prevent it. The baseline tools were prepared by the USAID-funded project’s regional technical team, for use in Honduras and other countries across the Latin American and Caribbean region. They were reviewed and adapted for use in Honduras by the Zika Strategic Command, the IHSS Zika team, and country-based technical staff of the USAID-funded project. The tools mainly focused on identifying whether Zika counseling and messages were being provided within key health services (family planning, prenatal, and postpartum care) and whether pregnant women could describe the risk of a Zika infection during pregnancy and ways to prevent Zika (including use of a condom to prevent sexual transmission of the virus), among other topics.

The baseline results showed that 20% of women of reproductive age and 22% of pregnant women could not identify Zika risks and complications (18/88). Only 43% of the women of reproductive age interviewed (40/107) could mention four or more personal protection measures to prevent Zika virus infection, but only 4% of these identified condoms as a protection measure against sexual transmission of the virus. When inquiring if the woman had received counseling on the risks of mother-to-child transmission of Zika while pregnant, 60% of patients who had visited an IHSS facility said they had received this information, but only 36% of those who had visited an MOH facility had.

At baseline, no clients were screened for Zika; however, a retrospective review of 145 patient records from the assessed facilities showed that 27% of sampled pregnant women had shown signs of an arbovirus-associated fever, 20% reported a skin rash, and 12% reported conjunctivitis – all potential signs and symptoms of Zika. At baseline, 75% of the 42 health facilities evaluated had condoms available. Less than half of health-care providers said that they had received training on Zika, and there were no standards or normative guidelines for Zika case management.

Development of and Training in Standards of Zika Care

Given the baseline results, a technical group of MOH , IHSS, and other organizations, led by the MOH General Directorate of Standardization with the support of the USAID-funded project, prepared normative guidelines for Zika-related care, which were approved at the end of 2016, for women of reproductive age with suspected or confirmed Zika infection during preconception, prenatal, postnatal, and postpartum stages and for infants or children with suspected congenital syndrome associated with Zika.

Regional MOH and IHSS coaches were identified and trained beginning in November 2016. These coaches then replicated the training on Zika guidelines for health-care providers in a two-and-a-half-day facility-level workshop, which they have delivered since January 2017. The coaches also received training on health-care improvement methods and tools.

The work to improve health care began by mid-2017. To strengthen Zika service delivery, the MOH and IHSS, with the support of the USAID project, developed collaborative improvement projects to implement Zika counseling in family planning (FP) services and in prenatal care and to screen newborns for microcephaly.

Formation of QI Teams

After the workshop for coaches, the health region management support units were instructed to organize three types of collaborative improvement teams within participating facilities: Zika prevention in family planning, Zika screening and prevention in prenatal care, and Zika screening in newborn care. Hospitals typically had all three teams. Primary care facilities organized only family planning and prenatal care teams; in facilities with a small number of staff, organization of the prenatal care team was prioritized. The regional teams sent instructions to facility managers to organize improvement teams of 6–8 persons following specific profiles. Upon implementing improvement work, many teams incorporated new personnel who were not initially considered while other team members dropped out because they were not involved in direct patient care.

Once the teams were organized, two training sessions (each lasting 2 days) were held at each facility, with a period of 2 weeks between them. In the first session, trainers addressed the general health-care improvement approach, developing improvement aims, forming the QI team, developing a flowchart of the current care process, and developing indicators to measure progress. The second session, held after teams had begun analyzing the gaps in their existing care processes, focused on measuring indicators, identifying changes to test, developing a flowchart of the ideal care process, creating time series charts, and preparing an action plan for testing changes and measuring results.

MOH Support for Improvement Teams

Coaching

After the training, QI coaches, selected by the MOH Quality Department and health region staff, followed up with each facility-level QI team to support the care improvement process they were designing and implementing. Many coaches also belonged to respective health region’s management support unit. Visits were scheduled in coordination with the MOH Quality Department or IHSS and with those responsible for the Zika response in the health region. The role of the national-level staff was to provide political support; keep the Service Network Directorate informed of the progress of activities; and attend meetings with the regional team and coaching meetings with improvement teams. In the case of IHSS, members of the Zika technical team from the USAID-funded project accompanied IHSS coaches on visits to QI teams.

Coaching meetings usually lasted 1 day, and if the facility had two or three improvement teams, the meetings would be longer to allow sufficient time to assist all three teams. During these meetings, the coach guided QI teams in conducting analysis of the improvement work, asking probes like: What is the indicator result? Did the change work? Was it enough? Do we need another change? In the event that the team had not collected data for the indicator, MOH, IHSS, and the USAID project coaches participated in data collection and analysis.

Monitoring of 12 performance indicators for the Zika response was implemented nationwide by the USAID-funded project in coordination with the MOH’s Information Management Unit (Unidad de Gestión de la Información). With technical assistance provided by the USAID-funded project, the Information Management Unit, in coordination with primary and secondary care facilities, prepared a monitoring plan and, subsequently, held workshops for regional managers in charge of health facility monitoring. They also developed an improvement database for health facility staff to use to input data collected at the facility level; facility-level data reports were then sent to the regional level, and the regional level sent them to the national-level MOH Information Management Unit.

The project, in coordination with the MOH and IHSS, conducted periodic visits to verify the validity of the data reported to the MOH’s Information Management Unit and the consistency of data in the registers, the monitoring instruments, and the improvement database. Results were analyzed in conjunction with the coaching team visit.

Shared Learning

Improvement teams from different health facilities working on the same (or similar) aims have much to learn from each other. The improvement coach’s role is fundamental in spreading learning. In Honduras, coaches shared successful ideas from one team with others and helped to transfer innovative change ideas from teams that had positive results to teams that did not experience such quick results. The coach’s expertise and experience also played an important role in honing ideas and changes and guiding implementation.

The USAID-funded project also provided funding for QI team members from one facility to visit the QI team of another health facility to learn about and see the changes they were making in practice to help them understand the feasibility of replicating the successful changes within their own facility. The visiting teams often asked for support in replicating successful change ideas. Many requests were made to expand the improvement process to other health facilities in regions where the project worked.

In addition, the USAID-funded project and the MOH organized national learning sessions to bring teams together to exchange experiences. At these sessions, the USAID-funded project team employed knowledge management techniques to ensure that participants had an opportunity to share what they had learned and were engaged to learn from others. Through the experiences and results shared during these learning sessions, project staff were able to compile best practices implemented by teams working to improve Zika care within family planning services.

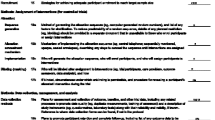

The first national learning session for the Zika family planning (Zika-FP) collaborative was held 6 months after starting the improvement process. Teams presented their changes and successful experiences in a series of interactive conversations that encouraged teams to learn from each other (see Box 5.1). The national learning session lasted for 2 days. Twenty-eight improvement teams in the Zika-FP improvement collaborative participated in the learning session, in addition to staff from the MOH, USAID, the USAID-funded project, and other implementing partners. During the session, the teams identified the changes that were currently being discussed for institutionalization. Table 5.1 shows a sample of the key changes that the Zika-FP teams recommended to others.

Box 5.1 Techniques to Foster Peer-to-Peer Learning

In preparation for the national learning session, coaches selected a few teams that had excellent results from the changes they had implemented to address their improvement aims. Coaches provided these teams with a tool to document their experiences and asked them to identify a member who would be working as the “speed consultant” during the session. Many of the teams made posters to convey their results. Session participants sat at eight tables with a speed consultant at each. The consultant would speak for 20 minutes about the experience of his or her improvement team, sharing successful changes. After 20 minutes, participants would move to a new table. Participants had the opportunity to buy – or not buy – change ideas, symbolically paying the speed consultant to purchase compelling ideas, which helped to give a value to successful change ideas. Participants at the tables could present and “sell” their changes, thus promoting learning across teams.

Improving Zika Counseling and Care Within Family Planning Services at Catacamas Polyclinic in Olancho

Catacamas Polyclinic , located in the city of Catacamas (population 40,912) in the Department of Olancho, offers specialty services for obstetrics and gynecology, prenatal ultrasonography, and pediatrics and has a special clinic to provide care to adolescents due to the high incidence of teenage pregnancy in the area served by this clinic.

The facility manager organized an improvement team composed of three nursing assistants (one of whom also served as the team coordinator), a professional nurse, and a general physician.

Setting Improvement Aims

The improvement team decided to focus on integrating Zika in FP services for two groups: women of reproductive age and adolescents (both female and male). They set a different improvement aim for each group, based on the team’s analysis of each group’s needs in the context of Zika.

Given that the emergence of Zika in the Americas was so new, few health facilities had any processes in place to include Zika within existing care processes. When the Zika-FP team at Catacamas Polyclinic first started working on this topic, they found that no women or adolescents attended at the facility were receiving information and counseling on Zika and its complications.

For women of reproductive age, they set this improvement aim: “To increase Zika counseling to clients, partners, and/or men of reproductive age who attend the clinic for FP services and/or psychological services, documenting the services provided in the patient’s medical record on a sheet designed for that purpose, from 0 to 100% between June 26 and December 31, 2017.”

Then, they selected an indicator to measure achievement of their aim:

-

Percentage of female and male family planning clients and/or partners who received FP/Zika counseling.

For adolescent care, they set this aim: “Increase knowledge about Zika virus prevention and transmission methods among the adolescent male and female population and/or partners that attend the adolescent care clinic by providing Zika counseling and/or Zika education sessions prior to clinical care (e.g., talks in the waiting room), during their medical appointment, and as they are exiting the health facility (educational room, comprehensive teenage counseling, consultation room, psychological care), documenting the care provided in the designated Zika counseling sheet, from 0 to 50% between June 26 and December 31, 2017.”

They selected these indicators to measure achievement of their aim:

-

Percentage of teenagers (male and female) and/or partners who attend the adolescent care clinic and receive counseling, information, and guidance on Zika virus infection.

-

Percentage of teenagers (male and female) and/or partners who demonstrate knowledge of Zika transmission and prevention methods.

Analysis of the Current Care Process to Identify Gaps

The team developed a flowchart of the existing care process for women of reproductive age and identified several problems. First, FP counseling was provided at the health facility through a nursing assistant trained as a counselor but who had other duties. FP counseling was only provided for some methods because the health facility has a high patient load, leaving the provider with little time for each woman and causing delays in receiving care. The FP service at the clinic had a FP counseling tool provided by MOH, but it was not used very often. This service was provided with limitations because the same counselor provided other reproductive health care. Zika counseling was not provided within family planning services or within psychology services. Even FP activities were not recorded on any form, except for a small note written in the medical record that read: “FP counseling provided.”

The team observed similar challenges with adolescent care. The adolescent care clinic had been established 2 months prior and had a private space specifically designated for comprehensive counseling and consultancy. Approximately 26–30 teenagers received care daily at the clinic, causing prolonged wait times for care. Zika counseling was not provided there either.

The adolescent counseling room already existed with sufficient privacy, but the improvement team arranged for additional furniture such as a couch and additional chairs. They decorated the room with flowers so that patients would find the space to be more attractive. They began to supply condoms to patients in small packets.

The counseling room also had a waiting area that could seat five persons, so the team decided to give group talks on Zika while patients were waiting to talk individually with the counselor. This allowed them to reduce the individual counseling time since they simply needed to review the adolescent’s understanding of the Zika counseling messages, which took less time than starting the counseling from scratch.

Some of the teams found that pregnant women would reject the condoms or throw them out after receiving them because they were afraid to ask their husbands to use them. To address this barrier, the teams began engaging men, holding meetings with them to discuss their role in preventing Zika transmission by using condoms.

Measuring Improvement

Team members met to review a sample of randomly selected files obtained from the facility’s statistics service. The improvement team found that the facility’s current performance was 0% in their defined indicators when they made the first measurements at the time of the training workshops. The QI team created a form where they documented the clients’ medical record number and listed messages on Zika signs and symptoms, transmission (mosquito bite, sexual, and mother-to-baby), prevention methods, personal protection measures, and complications, noting whether counseling was provided and whether it covered these key topics. This form served both as a means of data collection for the team and as a job aid for providers. The QI team also documented distribution of FP methods every month.

Data monitoring, which began in June 2017, was carried out on a weekly basis until January 2018, and monthly thereafter. Each week, a different person from the QI team was assigned to measure indicators. After they had collected data, the team would meet to consolidate and graph the results on a board provided by the USAID project for this purpose. The director of the health facility would include the indicator monitoring results as a topic of discussion during the monthly all-staff meeting.

Testing and Implementing Changes

Table 5.2 presents the first changes tested by the Catacamas team to reduce gaps in the quality of Zika care within family planning services.

For the first time, the facility staff began to recognize that counseling is a part of clinical care and began to understand the need to record it in order to follow up with the client. Also, around this same time, counseling services began to be recorded in the MOH official information system for the first time as part of changes initiated at the national level by the Zika Strategic Command.

Within a few weeks, the team realized that recording care was not useful if the service was disorganized. Under the original process of care, the doctor was responsible for providing Zika counseling, but patients mentioned that doctors used very technical language that they found difficult to understand. There was only one provider, an auxiliary nurse, who had been trained as a counselor, but this person was also providing other reproductive care services and could not cover everyone. In addition, counseling was not private, and family planning counseling was only provided for certain methods. The team decided to create a private space for counseling in the FP clinic. Initially, they assigned one counselor to provide counseling full time, but later, the facility trained more health-care providers as counselors (with MOH and USAID-funded project support). Currently, all nurses and the psychologist provide counseling, and there is a robust schedule of coverage to meet client demand while accommodating staff vacations, etc. The flow of care within the clinic was totally modified.

Changes introduced to improve the clients’ knowledge of Zika are described in Table 5.3.

To conduct exit interviews with clients, they requested help from the psychologist (who was not part of the improvement team at the time). The team wanted someone outside the team to collect this data, so that there would be no potential bias and the result would be more reliable. The psychologist would not tell anyone when she was conducting exit interviews. (After some time, the psychologist became part of the team and then became the coordinator of all the teams organized and functioning in the facility.) Clients were interviewed as they left the health facility, using a survey instrument developed by the MOH and the USAID-funded project. Once the clients’ knowledge had been assessed, the completed forms were shared with the improvement team for analysis and decision-making.

When analyzing the initial data from the exit interviews, the team realized that clients’ knowledge was still very poor. Then, the team decided to create a flipchart with standard Zika information to teach Zika signs and symptoms, transmission methods (including sexual transmission), prevention through personal protective measures, and complications. When this change was introduced, their indicator went up to 100%. However, in subsequent exit interviews, they continued to find clients lacking important Zika knowledge, so they decided to use other information, education, and communication techniques, such as group talks, posters, and involving teenagers to educate their peers, to promote learning.

Other Activities That Contributed to Improvement

-

Training counselors in long-acting reversible and permanent contraceptive methods.

-

The health manager hired two facility psychologists with MOH funds to provide counseling. The QI team integrated these staff members into the clinical care process.

-

Trained community leaders, educators, peer leaders, and an adolescent support committee. Because the staff in the facility had prior experience working with adolescents, the project sought to merely reinforce these activities, including training adolescents to lead group discussions with other adolescents about Zika and preventive topics. They coordinated with schools to reach those adolescents who were already attending the clinic to train them to work with groups of adolescents to teach them about the Zika virus and how to prevent its transmission.

-

Periodically during meetings with adolescents, they engaged health personnel to conduct demonstrations of correct condom use.

-

They provided condoms to clients in small packages.

-

Shared Zika information with the television media.

-

Created murals.

National-Level Monitoring of Zika Indicators

Apart from the indicators monitored at the health facility level by the team as part of the improvement process, indicators were also monitored for follow-up at the national level by the USAID-funded project. The MOH’s Information Management Unit started monitoring 12 Zika indicators with technical support from the project in June 2017. A monitoring plan was developed, followed by a monitoring plan training workshop to train health region technical teams and those responsible for monitoring and evaluating health facilities. Then, the Excel database provided by the USAID project was given to health facility staff, regions, and the MOH Information Management Unit. The indicator measurement report traveled from the team, who sent it to the database at the regional level; the regional level consolidated all the facility data and then sent it to the MOH Information Management Unit. Health regions also sent a copy to the MOH Quality Unit and the USAID project. This indicator monitoring motivated the facility teams to improve other indicators when results were not satisfactory.

Spreading the Knowledge

In February 2018, the MOH, with the support of the USAID-funded project, conducted a second national learning session for teams from different health facilities to meet and share learning from their work improving Zika care in family planning services. During the learning session, the Catacamas Polyclinic improvement team presented their successful experience, and other teams spoke with them to ask how they did it and what activities they implemented.

The changes made by QI teams to improve Zika counseling in family planning services were analyzed at the national-level MOH office, with support from the USAID-funded project. To further support the efforts of the facility-level teams, the national-level technical team identified a need to improve the chapter of the National Family Planning Strategy on organization of family planning services. The National Family Planning Strategy is the official document guiding family planning activities in Honduras and was developed with USAID funding in previous years.

The flipchart for Zika counseling prepared by the Catacamas team was adapted by the USAID-funded project to standardize it for all improvement teams. The topics of Zika counseling, counseling in the pre-conception stages, pregnancy, postpartum, etc., were added to the flipchart’s design.

The Catacamas Polyclinic decentralized services manager also identified successful changes made by the FP-Zika team that could be shared with lower level health facilities in the Catacamas catchment area that are part of the polyclinic’s decentralized health services network.

The Olancho Health Region, in view of the success of its health facilities with the Zika care improvement process in FP services, took the initiative to expand the process to other service networks within the region.

Reflection

The Olancho Region had a nurse leader, very empowered in her role as a regional Zika quality focal point. Within her role on the regional coordination team, she advocated for the need to expand the integration of Zika counseling in FP services to other health service networks.

As a result of the experience of the Catacamas Polyclinic, improvement teams have also been organized at the San Francisco de Juticalpa Hospital, which is the referral hospital in Olancho Health Region, some 30 minutes away from Catacamas. The hospital is now also providing Zika counseling and distributing condoms to both women of reproductive age and pregnant women to prevent sexual transmission of Zika.

An interesting piece of data from one of the quality improvement teams at the San Francisco de Juticalpa Hospital is the experience they had in the beginning of 2018. The MOH Management Planning Unit, which is in charge of planning and scheduling management activities at the national level, called the hospital’s improvement team to ask if there was an error in the data or why there was a difference in condom delivery, since they were surprised that the hospital had tripled the number of condoms distributed. The doctor in charge of handling the information responded, explaining that the situation was due to the fact that they were delivering condoms in the Zika prevention framework, to both women of reproductive age and pregnant women.

Other health regions also have expansion plans to implement the counseling process in FP and postnatal care services. Tulane University conducted a study in the Metropolitan Health Region of Tegucigalpa, which assessed the quality of Zika and FP services. The results indicated that health facilities that have quality improvement teams have better results than facilities that do not have them. Given these results, the Metropolitan Health Region requested the USAID project to support the expansion of improvement to other new facilities.

The work of the teams, using data and transforming their processes, does make a difference.

References

Carmenate-Milián L, Herrera-Ramos A, Ramos-Cáceres D, Lagos-Ordoñez K, Lagos-Ordoñez T, Somoza-Valladares C (2017) Situation of the health system in Honduras and the new proposed health model. Arch Med 9:4. https://doi.org/10.3823/1333

World Health Organization. International Health Regulations procedures concerning public health emergencies of international concern. https://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/pheic/en/

Acknowledgments

The Zika improvement work in Honduras was supported by the USAID Office of Health Systems through the USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems Project, implemented by University Research Co., LLC under Cooperative Agreement Number AID-OAA-A-12-00101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 University Research Co., LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Arnold, M.E.B., Leitzelar, N.A. (2020). Bridging the Gap Between Emergency Response and Health Systems Strengthening: The Role of Improvement Teams in Integrating Zika Counseling in Family Planning Services in Honduras. In: Marquez, L. (eds) Improving Health Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43112-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43112-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-43111-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-43112-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)