Abstract

This chapter enumerates the importance of small farms for food security, pulling together available studies and quantitative evidence on the current status of small farms in terms of their number, share of total farms, share in farmed area, employment share, age, gender, poverty and food insecurity status, importance in marketed surpluses of food staples, income diversification, etc. To the extent possible, trends in these variables are also enumerated, focusing on key questions such as: are small farms getting smaller (not just the average size of all farms); are they are becoming less important in total food supplies, especially marketed surpluses (needed to feed the cities); how successfully do they use high-value agriculture and nonfarm income diversification to offset smaller farm sizes. To the extent possible, differences in patterns between regions and types of countries are identified. Finally, some scenarios for the future are developed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Small farm-led development has been the dominant agricultural development strategy since its remarkable success in driving Asia’s Green Revolution. The paradigm is based on three major advantages claimed for small farms in poor, labour abundant countries.

-

Small farms are more efficient than large farms, as evidenced by an impressive body of empirical studies showing an inverse relationship between farm size and land productivity across Asia and Africa (Binswanger-Mkhize and McCalla 2010; Eastwood et al. 2010; Larson et al. 2014). Amongst other things, this means small farms can produce more food than large farms in a limited land area.

-

Small farms are the most populous farm size group, and they also farm large shares of the total agricultural area. As such, when scaled up, small farm development can have a big impact on agricultural growth and national food security.

-

Not only are small farms more efficient, but they also accounted for large shares of the rural poor. As such, small farm development can be a ‘win-win’ proposition for growth and poverty reduction.

There is much debate today about the continuing relevance of the small farm development paradigm. Important changes that may have eroded some of their perceived advantages include the following.

-

With continued population growth, small farms have shrunk in size, making it harder to support a family from farming alone.

-

Globalisation and market liberalisation policies have led to more consumer-driven food systems that are more dominated by large-scale players and place a greater emphasis on quality and safety attributes. Many small farms have difficulty connecting to such markets.

-

The substantial state interventions to support small farms, such as fertiliser subsidies and guaranteed markets, were removed as part of market liberalisation policies, with the theory that the private sector would fill the gap. The private sector did expand, but often not at sufficient scale, and many small farms lost access to key inputs and markets.

-

Many developing countries have reached middle-income status and are rapidly urbanising. One consequence is that rising labour costs are eroding some of the efficiency advantages of small farms and encouraging a shift towards more capital-intensive farming.

Despite these challenges and the pessimism of some authors (e.g. Maxwell et al. 2001; Collier 2009), small farms are not disappearing. Quite the opposite, they are multiplying, and in some countries are becoming even more dominant in the land distribution. This paper reviews recent changes in smallholder farming and explores some of the implications for food security.

2 Trends in the Number and Size of Small Farms

There are many possible definitions of small farms, but this chapter follows a common practice and defines smallholders as holdings of less than two hectares in size. A simple land-size definition enables the number of small farms to be enumerated using widely available agricultural census and household survey data, and facilitates comparisons across countries and over time. However, it can also be a misleading definition, because the economics of size depends on the quality of the available land, the prevailing agro-ecological conditions and the income-earning opportunities available to farmers. A ‘viable’ small farm might vary from just a couple of irrigated hectares of land in Asia to several hundred hectares of rainfed lands in parts of Latin America. But it can be much smaller if farming is combined with non-farm sources of income, as with many small, part-time farmers in Asia and Africa.

Some argue for a broader definition of smallholders, based on the concept of the family farm—farms that are operated by farm families using largely their own labour. Since just about every small farm is a family farm, this definition leads to higher estimates of the total number of ‘small’ farms. For example, in Latin America, there are about 5 million small farms less than 2 ha, but about 20 million family farms (Berdegué and Fuentealba 2014). A problem with using family farms as a definition of small farms is that they are not all small. In fact, many of the larger commercial farms found around the world are also family farms as defined above; they are just highly capitalised and mechanised ones. Attempts to draw a line between ‘small’ and ‘non-small’ family farms are sometimes made on the basis of assets (e.g. capital stock or machines), farm income or gross turnover. But this requires access to data that are not widely available, and definitions that are not easily comparable across countries and over time. The broader family farm approach is also less compelling for Asia and the more populous countries of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where the average farm size is well under 2 ha and there are relatively few large family farms.

Even with a land-based definition of size, obtaining reliable, recent and comparable cross-country data on trends in the number and size of small farms is still a challenge. The best data sources are national agricultural censuses since these adhere to established international guidelines and provide reliable information about the distribution of land as well as farm households (Lowder et al. 2016). The difficulty is that recent agricultural census data are not available for many countries, and most of the available data pertain to the late 1990s or early 2000s. More recent household surveys are available, such as the Living Standard Measurement Surveys (LSMSs), but because they are sampled to represent households and not agricultural area, they can seriously understate the importance of large farms, and hence distort estimated land shares. Also, most household surveys typically exclude farms that are not operated by farm families. Lowder et al. (2016) illustrate the problems by comparing census and household survey data from Guatemala, showing that while farms less than 3.5 ha accounted for 86% of all farms and 14% of the agricultural area in the 2003 agricultural census, a household survey conducted in 2006 found that the same size group accounted for 94% of all farms and 65% of the land area. Moreover, farms larger than 45.2 ha did not show up at all in the household survey but accounted for 57% of the land area in the 2003 agricultural census.

Based on agricultural census data from the 1990s and early 2000s, Lowder et al. (2016) estimate that there are about 570 million farms in the world, of which some 475 million (about 85%) are small (≤2 ha). About 90% of all farms are located in developing countries, and they are predominantly concentrated in Asia and Africa (60% of them are in China and India).

There has been a substantial increase in the number of small farms in recent decades. Since there does not seem to have been a comparable global estimate to Lowder et al. (2016) for an earlier period, it is necessary to fall back on census data for individual countries. Lipton (2009) reports changes between censuses for selected countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) (Table 1).

Except for Turkey, where the number of holdings and total area declined by about 20% between the two censuses, the number of holdings increased by between 12% (Uruguay) and 77% (Ethiopia) for all the other countries in Table 1; the unweighted average increase is 29%. The number of holdings of ≤2 ha also increased in all countries except Turkey. More recent data show that in India, the number of small farms ≤2 ha increased from 92.8 million in 1995–96 to 107.6 million in 2005–06, while their share in total farms increased to 83.3% (World Bank 2007).

The average size of farms has also shrunk in many countries, as shown in Table 2.

Although the overall trend is towards more and smaller farms, there are some regional and country variations in how the distribution of land is changing.

-

Farms are finally starting to get larger on average in China (up from 0.57 to 0.60 ha over the period 2005–2010) (Huang et al. 2012), but the more general pattern across Southeast Asia is still towards smaller farms. In the Philippines, the average operational farm size fell from 3.6 ha in 1971 to 2.0 ha in 2002, and the share of small farms ≤1 ha increased from 13.6 to 40.1%. Indonesia and Thailand saw more modest declines of 15–20% in average farm sizes over similar periods, but little change in the share of small farms ≤1 ha in size (Otsuka 2013).

-

In South Asia, the number of farms is still growing and average farm sizes are shrinking. In India, the average farm size approximately halved between 1971 and 2005–06, and in Bangladesh, the average operational farm size shrunk from 1.4 ha in 1976–77 to 0.3 ha in 2005 (Otsuka 2013).

-

African countries vary widely in their population densities, and farms are about half the size in highly populated countries than in less populated countries (Table 2; Jayne et al. 2016). Farm sizes have also shrunk the most in the highly populated countries; from around 2.3 ha in the 1970s to 1.2 ha in the 2000s, compared to a decline from 3.0 to 2.9 ha in less densely populated countries (Table 2; Jayne et al. 2016). Based on repeat household surveys in eight African countries, Jirström et al. (2011) found that even over the six-year period 2002–2008, average farm size declined by 15% in Ghana, 35% in Mozambique, 13% in Tanzania and 10% in Zambia, but remained unchanged in Kenya and Malawi, and increased by 9% in Ethiopia and by 37% in Nigeria. The average change across the eight countries was a decline of 11% (from 2.4 to 2.2 ha per holding).

-

In LAC, small family farms are typically larger than in Asia and Africa, and as defined by Berdegué and Fuentealba (2014), there are about 20 million of them (of which 5 million <2 ha). Their numbers are increasing in Central America but seem more stable across much of Latin America.

Small farms account for sizeable shares of the total farmed area in many Asian and African countries, but for much smaller shares in much of LAC (Table 1; Thapa and Gaiha 2014; Berdegué and Fuentealba 2014). Similarly, Lowder et al. (2016) estimate that small farms ≤2 ha account for 75–80% of all holdings in South Asia, SSA, and East Asia and Pacific (excluding China), and 30–40% of the agricultural area. In LAC, they estimate that about 25% of the holdings are ≤2 ha. These are predominantly concentrated in Central America and the Andes, and while important in some countries, they farm only a tiny share of the total agricultural area in LAC (Lowder et al. 2016).

3 Trends in Small Farm Livelihood Strategies

Many small farms have reached the point where they are now too small to provide a full-time living for a household, and this has led farm households to diversify into high-value farming, wage employment, migration, and other non-farm activity. In China, non-farm income shares for farm households increased from 33.7% in 1985 to 63% in 2000 and 70.9% in 2010 (Huang et al. 2012). This is an extreme example, but non-farm income shares have reached 40% or more in many other Asian and SSA countries and are often much higher for the smallest farms (Haggblade et al. 2007). In India, diversification has helped prevent widening income gaps between rural and urban households (Binswanger-Mkhize 2012). On average, this diversification is higher across Asia than Africa, but there is considerable variation within each continent.

Diversification is enabled by rapid urbanisation, and the growth of small- and medium-sized towns. Already, 37% of the population in Africa, 48% in Asia, and 80% in LAC live in urban areas, and the United Nations projects that by 2050, the urban population shares are expected to reach 56% in Africa, 64% in Asia and 86% in LAC (UN 2014). Urbanisation is not just about megacities. In fact, close to half of the world’s urban dwellers reside in relatively small settlements of less than 500,000 inhabitants, and these are often the fastest-growing urban areas. This has important implications for urban–rural linkages, enabling many households to combine farm and non-farm activities, even when living in urban areas. Often, they are living in areas that were previously defined as rural, and have become urban through census reclassification rather than any physical move.

4 Why the Slow Exodus of Small Farms?

Despite growth,—sometimes quite rapid growth—in national per capita incomes and urbanisation, we are not yet seeing the patterns of farm consolidation that occurred during the economic transformation of most of today’s industrialised countries. Rather, the continuing growth in smaller and more diversified farms might best be described as a ‘reverse transition’ (Hazell and Rahman 2014).

There are many factors driving this reverse farm size transition.

-

An important driver is rural population growth, especially growth in working-age adults. Other than China, few countries are generating enough jobs in urban-based manufacturing, which has historically been the primary absorber of rural–urban migrants. Instead, workers are moving into service sector jobs, many of which are based in medium- and smaller-sized towns, not just big cities, and this enables many rural households to diversify into non-farm employment from their farm base.

-

Rapid urbanisation, globalisation and a shift towards more diversified diets are creating greater opportunities for some small farms to succeed by growing and marketing high value, labour-intensive livestock and horticultural products (Joshi et al. 2007; McCullough et al. 2008).

-

The increasing use of subsidies and other agricultural support policies make small-scale farming more attractive than its real economic worth. China and many other Asian countries have already introduced farm support policies of various kinds, much as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan did during their economic transformation (OECD 2016).

-

There are also many country-specific institutional and cultural constraints that act to keep people on the farms, including:

-

constraints on rural–urban migration, such as language, racial, and cultural barriers; legal restrictions on resettlement (e.g. China);

-

inheritance systems that lead to subdivision of farms among multiple heirs;

-

restrictions on land market transactions, such as caps on farm size (India) or indigenous land rights systems that limit opportunities for land consolidation (Africa);

-

religious and cultural constraints on women’s employment opportunities other than farming;

-

inadequate social security systems, so that farms are kept as a retirement hedge.

-

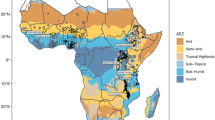

Many of these drivers are very powerful and seem unlikely to diminish in the near future. Take rural population growth, for example. Rural populations are projected to nearly double by 2050 in Africa, so the pressure on land will keep growing (Fig. 1). Rural population growth is slowing in much of Asia and will approach tipping points by 2030, at which point the pressure on the land base will begin to reverse. This has already happened in Bangladesh and China and may be happening more widely in dynamic regions with good market access within countries (Masters et al. 2013).

Source United Nations (2018)

Projected growth in rural populations.

5 Prognosis

Should we expect much change in these patterns over the next two to three decades? Much will depend on rates of national economic growth and the non-agricultural employment intensity of that growth. But rapid farm consolidation does not necessarily follow from economic growth, because of some of the constraints listed above. Moreover, rapid urbanisation, and particularly the growth of small- and medium-sized towns, increases opportunities for farm households to diversify into non-farm sources of income from a farm base.

The earlier experiences of Japan, Taiwan and South Korea suggest that in Asia, the dominance of small farms could continue well into middle-income status (Otsuka 2013). In Japan, for example, the average farm size only started to increase quite recently despite the country’s rapid economic take-off in the 1960s. The average farm size was still only 1.8 ha in 2005, and the percentage of farms ≤3 ha was still 90.5%.

Small farms not only dominate the total number of holdings in Asia and Africa, but as data from the 1990s and early 2000s show, they have typically retained large land shares, leaving little room for the emergence of many medium-sized and large farms. In some countries (e.g. Bangladesh, India and the Philippines), even the total agricultural land area is becoming more concentrated among small farms, and it is the large farms that are being squeezed out. On the other hand, there is evidence that some consolidation of operated, rather than owned, farmland is occurring in some countries, with small farms renting out some of their land to larger-scale operators (Otsuka 2013). In another development, Jayne et al. (2016) found that pockets of medium-sized farms are emerging in parts of Kenya, Malawi and Zambia, some of which are operated by urban-based investor farmers.

Another reason to think there may be greater land consolidation in the future is that the average age of farmers is increasing (currently about 60 years in Africa), and some land consolidation may eventually occur as part of an intergenerational transition. However, this may be offset by offspring who have left farming to work elsewhere but return to the farm when they retire, a not uncommon practice in many Asian and African countries. We simply do not know much about these possible demographic trends.

While things will eventually change, widespread land consolidation could be decades away. In the meantime, agricultural development is going to be largely all about small farms.

What we may see in the future is an increasing diversity of farm household livelihoods, with increasing gaps.

-

1.

Gaps between commercially oriented small farms that are well linked to value chains and a much larger number of subsistence or non-farm-oriented farms. Christen and Anderson (2013) estimate that only about 35 million of the world’s small farms (about 8%) participate in tight value chains, implying that the vast majority of small farms are being left behind.

-

2.

Gaps between small farms in favourable areas with good market connectivity and those in poorly connected and often marginal areas (lagging regions). This has already happened in much of South Asia, where rural poverty is now concentrated in lagging regions (Ghani 2010).

This increasing diversity will be a challenge for future assistance programmes for small farms, and interventions will need to be more carefully targeted. Several small farm typologies have been proposed in the literature to help guide such strategies, which have been summarised into three classes of small farms (Dorward et al. 2009; Hazell and Rahman 2014):

-

Commercially oriented small farmers already successfully linked to value chains, or who could link if given a little help. Many commercially oriented small farms are part-time farmers.

-

Small farms in transition, who have favourable off-farm opportunities and are at various stages of exiting farming as a serious business.

-

Subsistence-oriented small farms marginalised for a variety of reasons that are hard to change, such as being located in remote areas with limited agricultural potential, or representing elderly or infirm farmers. Many of the same factors also prevent them from accessing non-farm jobs and becoming transition farmers.

The relative importance of these three small farm groups varies widely from region to region. In a less favoured region of a slow-growing country—the worst of all possible worlds, and a situation all too prevalent in Africa—there are relatively few market-oriented farms, but many subsistence-oriented small farmers, including those who are trying to transition out of farming but cannot because of a shortage of off-farm opportunities. At the other extreme, in a dynamic region of a dynamic country—such as some of the coastal areas in China—many small farmers are producing lots of high-value products for the market, or are transitioning into better-paid opportunities in the industrial areas and in their local non-farm business economy. Relatively, few subsistence-oriented farmers remain, and these are often the elderly or the infirm. Many other regions, of course, fall somewhere between these two extremes.

With economic growth and urbanisation, significant numbers of commercially oriented small farms are likely to prosper through diversification into high-value agriculture. The most successful small farmers will tend to be located in areas with good agricultural potential and market access. Over time, some commercially oriented small farmers will become medium or large farms, while others will eventually become transition farmers or successfully exit farming to the non-farm economy. Transition farmers will either have, or will be able to develop, suitable skills and assets for undertaking non-farm activity, and they are likely to live in well-connected areas with access to off-farm opportunities. Their farming activities are likely to be oriented towards their own consumption rather than the market. Subsistence-oriented farmers are more likely to persist in less favoured and tribal areas and to grow traditional food staples (both crop and livestock) for their own consumption.

Hazell and Rahman (2014) discuss the kinds of interventions that may be relevant for each of the three groups of small farms. Commercially oriented small farms need support as farm businesses. They need access to improved technologies and natural resource management (NRM) practices, modern inputs, financial services and markets, and secured access to land and water. Much of this assistance will need to be geared towards high-value production and provided on a business basis. Many smallholders will also require help acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills to become successful business entrepreneurs in today’s value chains, especially women and other disempowered groups. Managing market and climate risk are challenges for many small farms; in addition to insurance and access to safety nets, these farms need to develop resilient farming systems.

Transition farmers need help for developing appropriate skills and assets to succeed in the non-farm economy, including, in many cases, assistance in developing small businesses. This can be especially important for women and other disempowered groups who have little experience working off-farm. The transition to the non-farm economy might also be facilitated by securing land rights and developing efficient land markets, so that transition farmers can more easily dispose of their farms. Since many transition farmers seem likely to continue to remain as part-time farmers, they can also benefit from improved technologies and NRM practices that improve their farm productivity.

Subsistence farmers are predominantly poor and will mostly need some form of social protection, often in the form of safety nets, food subsidies or cash transfers. Interventions that help to improve the productivity of their farms (e.g. better technologies and NRM practices) can make important contributions to their own food security, perhaps provide some cash income, and in many cases may prove more cost effective than some forms of social protection. Subsistence farmers have limited ability to pay for modern inputs or credit; however, so intermediate technologies that require few purchased inputs may be needed, or inputs will need to be heavily subsidised. Subsistence farmers are typically the most exposed and vulnerable to climate risks, and in addition to safety nets, they need help developing resilient farming systems.

6 Some Implications for Food Security and Nutrition

During the Green Revolution in Asia, small farms produced important amounts of the food staples that fed the cities as well as the countryside. Today, small farms are much smaller in size, and many are net buyers rather than net sellers of food staples. They are still able to provide for the food security of huge numbers of rural people, but it seems likely they contribute relatively little towards feeding urban populations.

Empirical evidence on these relationships is scarce. Available data on the share of marketed surpluses supplied by different farm size groups (e.g. Jayne et al. 2016) do not necessarily show this decline, because they do not differentiate between sales consumed in rural areas and sales consumed in urban areas. However, a recent study by Herrero et al. (2017) using spatial referenced data for 2005 provides some relevant insights. They show that, on average, small farms ≤2 ha produce about 55% of total cereals in China, 30% in Africa and Asia (excluding China), 10% in West Asia and North Africa, 15% in Central America, and negligible shares in South America (Table 3). Middle-sized farms of 2–20 ha are more important producers everywhere, except China, and large farms >20 ha dominate in Central and South America.

The importance of these results is that the small farm share in total cereal production in each region is considerably less than the corresponding rural population share (last column of Table 3), implying that in aggregate, small farms are no longer able to meet all the food staple needs of rural populations, let alone feed growing urban populations. It can be inferred that on balance, urban populations are now being fed mainly by medium-sized and large farms and from imports. In China, the small farm share in cereals production is still larger than the rural population share, so small farms may still be important suppliers to the urban market. Similar regional findings by Herrero et al. (2017) hold for the production of other food staples such as roots and tubers.

Urban population shares are projected to grow strongly across the developing world, and feeding these populations will require even more rapid growth in marketed food surpluses. It follows that for many countries, a national security agenda for food staples needs three pillars. One pillar is to provide support to the many smallholders who farm largely to meet their own subsistence needs. A second pillar is to support those farms that can produce marketed surpluses for the cities, and which are increasingly likely to be medium- and larger-scale farms. The third pillar is an appropriate international trade policy to enable imported food staples to fill remaining gaps.

Many small farms, particularly those located in well-connected areas, do have a comparative advantage in growing labour-intensive, high-value products like fruits, vegetables and milk, and this means they can contribute to more diversified and nutritionally rich diets in both rural and urban areas.

7 Conclusions

Overall, there are more small farms than ever today, and they are getting smaller, less important for supplying urban areas with food staples, and more dependent on non-farm sources of income for their livelihoods. However, there is considerable country and regional variation around this broad narrative. Small farms are not getting smaller everywhere, and in some countries, land is beginning to be consolidated into larger-sized holdings, even if only for operational purposes. Some small farms are also successfully marketing high-value perishable products like fruits, vegetables and milk, though relatively few are successfully linking into modern value chains. Non-farm income diversification is proving a successful livelihood strategy for small farms in fast growing countries and urbanising regions where more opportunities abound, but for many others, it is little more than a coping strategy that prevents or slows the descent into deeper poverty.

Several conclusions can be drawn from this analysis. First, small farm assistance programmes need to be cognisant of the growing diversity of small farm situations today, and to build strategies appropriate to each. These may need to distinguish between subsistence-oriented and market-oriented small farms, and small farms that are at various stages of transition out of farming through non-farm income diversification. It may also be necessary to differentiate between small farms that live in dynamic versus lagging regions, because of the different opportunities and constraints they face. This targeting requires the development and use of small farm classification schemes or typologies, and their operationalisation through appropriate mapping techniques (Hazell and Rahman 2014).

Second, national food security strategies need to be structured around three pillars. One pillar is to provide support to the many smallholders who farm largely to meet their own subsistence needs. The second pillar is to support investment in those farms, mostly medium- and large-scale farms, that can produce the marketed surpluses needed to feed the cities. The third pillar is an appropriate international trade policy to enable imported food staples to fill remaining gaps. The first of these pillars requires active public sector and NGO engagement with small farms, while the second pillar requires a proactive business agenda led by private sector initiatives.

Third, small farms have an important role to play in providing more diverse and nutritionally rich diets, both in producing a diverse array of food for their own and local market needs, but also help to provide urban areas with higher value and labour-intensive foods.

References

Berdegué, J. A., & Fuentealba, R. (2014). The state of smallholders in agriculture in Latin America. In P. Hazell & A. Rahman (Eds.), New directions for smallholder agriculture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Binswanger-Mkhize, H. (2012). India 1960–2010: Structural change, the rural non-farm sector, and the prospects for agriculture. Center on Food Security and the Environment, Stanford Symposium Series on Global Food Policy and Food Security in the 21st Century, Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Binswanger-Mkhize, H., & McCalla, A. F. (2010). The changing context and prospects for agricultural and rural development in Africa. In P. Pingali & R. Evenson (Eds.), Handbook of agricultural economics (Vol. 4, pp. 3571–3712). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Christen R., & Anderson, J. (2013). Segmentation of smallholder households: Meeting the range of financial needs in agricultural families, Focus Note No. 85, CGAP, April.

Collier, P. (2009). Africa’s organic peasantry: Beyond romanticism. Harvard International Review, Summer 62–65.

Dorward, A., Anderson, S., Nava, Y., Pattison, J., Paz, R., Rushton, J., et al. (2009). Hanging in, stepping up and stepping out: livelihood aspirations and strategies of the poor. Development in Practice, 19(2), 240–247.

Eastwood, R., Lipton, M., & Newell, A. (2010). Farm size. In P. Pingali & E. Robert (Eds.), Handbook of agricultural economics, Volume 4, (pp. 3323–3397). Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Ghani, E. (Ed.). (2010). The poor half billion in South Asia: What is holding back lagging regions? New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Haggblade, S., Hazell, P., & Reardon, T. (Eds.). (2007). Transforming the rural nonfarm economy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hazell, P., & Rahman, A. (2014). Concluding chapter: The policy agenda. In P. Hazell & A. Rahman (Eds.), New directions for smallholder agriculture (pp. 527–558). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Headey, D. (2016). The evolution of global farming land: Facts and interpretations. Agricultural Economics, 47(S1), 185–196.

Herrero, M., Thornton, P. K., Power, B., Bogard, J., Remans, R., Fritz, S., Gerber, J, Nelson, G., See, L., Waha, K., Watson, R., West, P., Samberg, L., van de Steeg, J., Stephenson, E., van Wijk, M., & Havlik, P. (2017). Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: A transdisciplinary analysis. Lancet Planet Health, 1(1): e33–42. http://thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanplh/PIIS2542-5196(17)30007-4.pdf.

Huang, J., Wang, X., & Qui, H. (2012). Small-scale farmers in China in the face of modernisation and globalisation. London/The Hague: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)/Hivos.

Jayne, T. S., Chamberlin, J., Traub, L., Sitko, N., Muyanga, M., Yeboah, F. K., Anseeuw, W., Chapoto, A., Wineman, A., Nkonde, C., Kachule, R. (2016). Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: the rise of medium-scale farms. Agricultural Economics, 47, 197–214.

Jirström, M., Andersson, A., & Djurfeldt, G. (2011). Smallholders caught in poverty—Flickering signs of agricultural dynamism. In G. Djurfeldt, E. Aryeetey, & A. Isinika (Eds.), African smallholders: Food crops, markets and policy (pp. 74–106). Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI.

Joshi, P. K., Gulati, A., & Cummings, R., Jr. (Eds.). (2007). Agricultural diversification and smallholders in South Asia. New Delhi, India: Academic Foundation.

Larson, D., Otsuka, K., Matsumoto, T., & Kilic, T. (2014). Should African rural development strategies depend on smallholder farms? An exploration of the inverse-productivity hypothesis. Agricultural Economics, 45(3), 335–367.

Lipton, M. (2009). Land reform in developing countries. London and New York: Routledge.

Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J., & Raney, T. (2016). The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development, 87, 16–29.

Masters, W. A., Djurfeldt, A., De Haan, C., Hazell, P., Jayne, T., Jirström, M., Reardon, T. (2013). Urbanization and farm size in Asia and Africa: Implications for food security and agricultural research. Global Food Security, 2(3), 156–165.

Maxwell, S., Urey, I., & Ashley, C. (2001). Emerging issues in rural development: An issues paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.

McCullough, E. B., Pingali, P. L., & Stamoulis, K. G. (Eds.). (2008). The transformation of agri-food systems; globalization, supply chains and smallholder farms. London and Sterling, Virginia: FAO and Earthscan.

OECD. (2016). Producer and consumer support estimates. Online database Accessed at www.oecd.org.

Otsuka, K. (2013). Food insecurity, income inequality, and the changing comparative advantage in world agriculture. Agricultural Economics, 44(s1), 7–18.

Thapa, G., & Gaiha, R. (2014). Smallholder farming in Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and opportunities. In P. Hazell & A. Rahman (Eds.), New directions for smallholder agriculture (pp. 527–558). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

United Nations. (2018). World urbanization prospects; the 2018 revision. United Nations, New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

World Bank. (2007). World development report 2008: Agriculture for development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hazell, P. (2020). Importance of Smallholder Farms as a Relevant Strategy to Increase Food Security. In: Gomez y Paloma, S., Riesgo, L., Louhichi, K. (eds) The Role of Smallholder Farms in Food and Nutrition Security. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42148-9_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42148-9_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-42147-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-42148-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)