Abstract

FANchild (French Affective Norms for Children) provides norms of valence and arousal for a large corpus of French words (N = 720) rated by 908 French children and adolescents (ages 7, 9, 11, and 13). The ratings were made using the Self-Assessment Manikin (Lang, 1980). Because it combines evaluations of arousal and valence and includes ratings provided by 7-, 9-, 11-, and 13-year-olds, this database complements and extends existing French-language databases. Good response reliability was observed in each of the four age groups. Despite a significant level of consensus, we found age differences in both the valence and arousal ratings: Seven- and 9-year-old children gave higher mean valence and arousal ratings than did the other age groups. Moreover, the tendency to judge words positively (i.e., positive bias) decreased with age. This age- and sex-related database will enable French-speaking researchers to study how the emotional character of words influences their cognitive processing, and how this influence evolves with age. FANchild is available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Catherine_Monnier/contributions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the field of emotion and cognition, a wide range of studies have examined how emotional words are processed by comparing them to neutral words. These studies have used various experimental paradigms, including the emotional Stroop task (e.g., Dresler, Mériau, Heekeren, & van der Meer, 2009; Koven, Heller, Banich, & Miller, 2003), the lexical decision task (e.g., Kuchinke, Võ, Hofmann, & Jacobs, 2007; Syssau & Laxén, 2012; Windmann, Daum, & Güntiürkün, 2002), immediate serial recall (Majerus & D’Argembeau, 2011; Monnier & Syssau, 2008; Tse & Altarriba, 2009), and the directed-forgetting paradigm (Korfine & Hooley, 2000; Minnema & Knowlton, 2008). However, these studies would not have been possible without the efforts of researchers to establish norms for the emotional characteristics of words. The aim of this study was to provide an age-adapted tool for future research on the processing of emotional words from a developmental point of view. Syssau and Monnier (2009) already proposed a French child database containing a corpus of 600 French words that were rated on emotional valence by French children using a nominal 3-point scale (i.e., positive, neutral, and negative). A new database is presented here: It is based on Bradley and Lang’s (1999) procedure and contains valence and arousal ratings by children and adolescents for 720 French words.

In 1999, Bradley and Lang published the now-authoritative Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) database. This database was developed within the dimensional theory of emotions, in line with Osgood’s semantic differential theory (Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957). This view posits that emotional meaning can be described by two main dimensions, valence and arousal, and by a third, less strongly related dimension, dominance or control. Emotional valence and arousal can be represented in a bidimensional framework called the affective space. The ANEW database provides valence, arousal, and dominance norms for 1,034 English words compiled from evaluations using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Lang, 1980). SAM is a picture-based instrument, in which each dimension is represented graphically (with a character) on a 9-point scale. For the valence dimension, the SAM scale ranges from a happy-looking, smiling character on the left to a frowning, sad-faced character on the right. For the arousal dimension, the character on the left is wide-eyed and looks excited, whereas the character on the right has eyes closed and looks calm and sleepy. For the dominance dimension, the character on the left is small to show that it is dominated, and the character on the right is large to show maximum control. The ANEW database provides means and standard deviations for the valence, arousal, and dominance ratings averaged across all participants, then averaged across both male and female participants.

The ANEW American database has been adapted to other languages, including Spanish (Redondo, Fraga, Padrón, & Comesaña, 2007), Portuguese (Soares, Comesaña, Pinheiro, Simões, & Frade, 2012), and Italian (Montefinese, Ambrosini, Fairfield, & Mammarella, 2014). These works have clearly demonstrated that the emotional meanings of words vary with languages and cultures. This finding underlines the need for specific tools in every language. In French, FAN provides valence and arousal norms for 1,031 words rated by young adults with the standard SAM (Monnier & Syssau, 2014).

Another factor of variability of the emotional meanings of words seems to be sex. Although some studies have found no difference between the affective ratings made by males and females (e.g., Redondo et al., 2007), or only minimal sex-related differences (e.g., Stevenson, Mikels, & James, 2007), other studies have shown that levels of reactivity to emotional words were higher for females than for males (e.g., Monnier & Syssau, 2014; Montefinese et al., 2014). Therefore, since sex may be a differentiating factor in word evaluations, and consequently in participant performance in a wide range of cognitive tasks, researchers need a tool that would allow them to take into account sex-related differences.

In addition to language and sex differences, the emotional meanings of words also seem to vary with age. Age-related differences in emotional content have been evidenced when words were rated by young and older adults (Gilet, Grühn, Studer, & Labouvie-Vief, 2012; Grühn & Smith, 2008; Keil & Freund, 2009). Grühn and Smith developed the AGE database (Age-Dependent Evaluations of German Adjectives), which was compiled with ratings of 200 German adjectives by young (20–30 years of age) and older (65–76 years of age) adults. Age-related differences were observed for 31 % of the adjectives in valence ratings and for 21 % of the adjectives in arousal ratings. Furthermore, positive adjectives were more positive and more arousing for older than for young adults. In contrast, negative adjectives were evaluated as being less arousing by older adults than by young ones. At the other end of the age range, Syssau and Monnier (2009) found that evaluations of the emotional meanings of words changed substantially between the ages of 5 and 9 years. The number of words rated as neutral increased between the ages of 5 and 7, whereas the number of words rated as positive decreased between 5 and 9 years old. Only the number of words rated as negative remained stable with age. From a purely quantitative point of view, there was a significant change in valence with age for 5 % of the words evaluated by the children. Such findings underline the importance of providing age-adapted tools to researchers so they may examine, from a developmental point of view, how emotional words are processed.

Studies interested in how emotional stimuli are processed by children remain scarce, but a significant increase in their number is noticeable. For instance, recent studies have focused on the cost effects associated with processing emotional distractors in children and adolescents (Cohen-Gilbert & Thomas, 2013; Heim, Ihssen, Hasselhorn, & Keil, 2013), emotional reactions to facial emotional expression during childhood (Mancini, Agnoli, Baldaro, Ricci Bitti, & Surcinelli, 2013), affective reactions in anxious children (Kotta & Szamosközi, 2012), attentional or memory bias for emotional information in both child and adolescent emotionally disordered samples (Moradi, Taghavi, Neshat-Doost, Yule, & Dalgleish, 2000; Neshat-Doost, Moradi, Taghavi, Yule, & Dalgleish, 2000), false memory (Brainerd, Holliday, Reyna, Yang, & Toglia, 2010; Howe, Candel, Otgaar, Malone, & Wimmer, 2010), and the influence of emotional valence on children’s recall (Syssau & Monnier, 2012; Van Bergen, Wall, & Salmon, 2015). Despite the increasing interest in emotional word processing within a developmental perspective, few norms providing children’s or adolescents’ emotional ratings have been published yet (Syssau & Monnier, 2009, in French; Vasa, Carlino, London, & Min, 2006, in English; Ho et al., 2015, in Chinese). In Syssau and Monnier (2009), we collected valence ratings of 200 words at age 5, 588 words at age 7, and 600 words at age 9 using a 3-point pictorial scale of face drawings, with a sad mouth for negative valence, a straight mouth for neutral valence, and a smiling mouth for positive valence. Vasa et al. provided valence ratings for a preselected list of 81 words from three emotional categories (threat, positive, and neutral), rated by children 9, 10, and 11 years of age using the SAM scale reduced to five points. Ho et al. collected ratings of valence, arousal, and threat for 160 Chinese words among adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years old. To date, these databases are still underused in this domain of research; this is probably due to the facts that (a) two of them provide valence but not arousal ratings, and (b) the numbers of words rated by children have been rather small. Though researchers have not specifically used child norms to carry out their studies, they have usually selected emotional stimuli on the basis of pilot studies in which another sample of children rated the material on emotional characteristics (i.e., Syssau & Monnier, 2012). Occasionally, researchers selected the experimental words on the basis of valence and arousal ratings collected from adults rather than children (i.e., Brainerd et al., 2010). This kind of strategy raises questions. Indeed, Kensinger, Brierley, Medford, Growdon, and Corkin (2002) observed that the effects of age on the recall of positive and negative words could depend on the criteria used for word selection. When the positive and negative words were categorized on the basis of how they were evaluated by young and older adults, older adults recalled more negative words than positive ones, whereas young adults recalled more positive than negative words. Conversely, when the positive and negative words were categorized on the basis of the evaluations included in the ANEW, both older and younger adults recalled more positive than negative words. Consequently, it is important to systematically verify that the emotional words selected for a study are suited to the participants’ ages.

The objective of our work was to provide French-speaking researchers with a tool that would allow them to more closely examine how a word’s emotional characteristics influence its processing in children and adolescents. Our database provides emotional evaluations obtained from four different age groups (7-, 9-, 11-, and 13-year-olds). This age range allowed us to determine whether the perception of words’ emotional significations changes with age. Our database provides both valence and arousal evaluations, so researchers will be able to manipulate and/or control both of these dimensions in children and adolescents. The SAM (Lang, 1980) was used to assess both valence and arousal. Since this scale is a nonverbal, pictographic self-report measure, it can easily be implemented with children. After noticing that, in a pilot study, 7-year-old children failed to understand the instructions and were then unable to use the scale correctly, we decided not to evaluate the dominance emotional dimension.

Method

Participants

We recruited 908 participants for the study: 208 seven-year-olds (109 girls, 99 boys; mean age = 7 years 7 months, range = 7 years 1 month to 8 years 1 month, SD = 4 months), 204 nine-year-olds (107 girls, 97 boys; mean age = 9 years 7 months, range = 9 years 1 month to 10 years 1 month, SD = 4 months), 262 eleven-year-olds (126 girls, 136 boys; mean age = 11 years 7 months, range = 11 years to 12 years 2 months, SD = 4 months), and 234 thirteen-year-olds (119 girls, 115 boys; mean age = 13 years 8 months, range = 12 years 8 months to 14 years 2 months, SD = 4 months). All were native speakers of French. The entire sample was recruited from a number of elementary and middle schools located in or around the cities of Arles and Montpellier in the south of France. These areas include a broad range of socioeconomic strata. Parental informed consent was obtained for all children and adolescents, who participated voluntarily to the study.

Materials and procedure

The stimulus set contained 720 French nouns drawn from the FAN emotion database compiled by Monnier and Syssau (2014). The 720-word corpus was selected on the basis of age of acquisition (7 years) as defined in Ferrand, Grainger, and New (2003), Lachaud (2007), and Niedenthal et al. (2004). We divided the entire corpus into 12 questionnaires of 60 words and developed two versions of a questionnaire with the same words arranged in two different randomized orders.

The 60 words in each questionnaire were printed in an eight-page (A4 size) test booklet. The front page included a section in which participants gave personal information (first name, sex, date of birth, and school) and presented two practice words. Pages two to seven contained nine words and page eight contained six words. Each word was printed in the center of the page in Times 14-point font. The valence and arousal scales from the paper-and-pencil version of the 9-point SAM scale (Lang, 1980) were printed under each word, with the valence scale on the left and the arousal scale on the right (see FAN: Monnier & Syssau, 2014).

We followed identical procedures for the 7- and 9-year-old children, who were tested in groups in a quiet room at their school. Each child rated two questionnaires of 60 words each in two separate sessions, carried out within a period ranging from one day to one week. The first session lasted approximately 45 min; the second session lasted approximately 30 min. The instructions were adapted from Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert (2008, instructions for child participants). The experimenter first described the valence and arousal scales, and explained how to use both scales to evaluate personal feelings. The booklets were then given out and the children were asked to fill in their personal information. Next, the two practice words were reviewed. The experimenter and the children read each word aloud together and the children were instructed to put an X above the picture of the manikin that best described their initial feeling upon hearing the word. They were told to do this first for the valence scale and then for the arousal scale. The aim of the practice trials was two-fold: First, we wanted to ascertain that the children perfectly understood the instructions; second, we meant to show that many answers were possible—that is, that there were no right or wrong answers. After the two practice trials, the experimenter read aloud the first word of the questionnaire and asked the children to fill in the valence and arousal scales. Once the children had done so, the next word was read aloud. If any of the children needed more time, testing was paused so they could be helped. A similar procedure was used for the second testing session, except that the children did not rate any practice words.

The 11- and 13-year-old participants were tested in groups in a quiet room at their middle school. Each participant rated two booklets of 60 words each in a single session lasting approximately 45 min. The instructions were adapted from Lang et al. (2008, instructions for adults participants). After listening to the instructions and rating the two practice words, the participants read each word silently and rated it on the valence and arousal scales, proceeding at their own pace.

Results

Description of FANchild

Each word was rated by at least 31 seven-year-olds, 27 nine-year-olds, 40 eleven-year-olds, and 36 thirteen-year-olds. For each word, we calculated the mean valence and mean arousal scores for each age group and sex, and compiled the affective ratings into a database. Column 1 of the database lists the 720 words in alphabetical order. An English translation is given in column 2. Although our materials consisted of words, column 3 lists picture sources (when available: “AF” indicates Alario & Ferrand, 1999, and “B,” Bonin, Peereman, et al., 2003); this information may prove helpful in future studies, especially those involving children. Column 4 indicates the number assigned to each picture. Columns 5 to 52 show the valence and arousal mean ratings (Mean) and standard deviations (SD) for each of the 720 words. For each age group, these data are given for the total sample (All) and for the boy and girl samples separately. Columns 53 (Frequency 7 years) and 54 (Frequency 8–11 years) show the written frequencies of use for each lemmatized word (U estimated frequency per million words) for two age groups (7-year-olds and 8- to 11-year-olds) according to the MANULEX database (Lété, Sprenger-Charolles, & Colé, 2004). Five additional objective psycholinguistic indices, all taken from Lexique 3.80 (New, Pallier, Brysbaert, & Ferrand, 2004), are given in columns 55 to 59: lexical frequency (occurrences per million words, o.p.m.) in films, collected from the subtitles of a variety of films (column 55); lexical frequency in books, based on written sources (column 56); number of letters (column 57); number of phonemes (column 58); and number of syllables (column 59). Column 60 lists the mean ratings for the subjective psycholinguistic index imageability (from 1 [very low imagery value] to 7 [very high imagery value]), taken from Bonin, Méot, Ferrand, and Roux (2011), Desrochers and Bergeron (2000), and Gonthier, Desrochers, Thompson, and Landry (2009).

Descriptive statistics

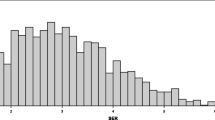

Descriptive statistics for both the valence and arousal ratings and for each age group and sex are reported in Table 1. Figures 1 and 2 show the distributions of both valence and arousal ratings for 7-, 9-, 11-, and 13-year-olds.

The distributions of valence ratings are negatively skewed at 7, 9, and 13 years of age (G1s = –.50, –.17, and –.02, respectively) and positively skewed at 11 (G1 = .09). From 7 to 13 years of age, the distributions of mean valence ratings move from the right (i.e., positive) toward the center of the scale (i.e., neutral). We effectively observed that 79 %, 69 %, 61 %, and 62 % of the words were rated above the middle of the valence rating scale—that is, above 5—at 7, 9, 11, and 13 years old, respectively. The tendency to judge words positively (i.e., positive bias) decreases with age, particularly between 7 and 11 years. The presence of a positive bias is consistent with previous normative studies of adult participants (Montefinese et al., 2014; Warriner, Kuperman, & Brysbaert, 2013). The finding that positive bias decreases with age supports our previous one; indeed, in Syssau and Monnier (2009), we asked 5-, 7-, and 9-year-old children to evaluate valence on a 3-point scale (positive, neutral, negative). We found that the ratings of 5- to 9-year-old children tended to shift from the positive to the neutral area of the valence scale.

The distribution of arousal ratings is positively skewed at 7, 9, 11, and 13 years old (G1s = .10, .55, .68, and .44, respectively). Unlike valence ratings, the distribution of mean arousal ratings does not cover the entire scale. Extreme mean arousal ratings were rather rare (i.e., below the value “3” or above the value “7”). We observed that only a relatively small number of words excited participants 9, 11, and 13 years of age (36 %, 36 %, and 41 % of the words were rated above the middle of the arousal scale—i.e., 5—at 9, 11, and 13 years, respectively), confirming the findings of Warriner et al. (2013). In contrast, 62 % of the words were rated above the middle of the scale by 7-year-old children.

Reliability of valence and arousal ratings

To estimate interrater reliability, the split-half method was implemented. We randomly formed two subgroups of participants within each of the four age groups and calculated the mean ratings for each word. We then correlated the mean ratings from both subgroups of participants for the two affective dimensions (i.e., valence and arousal). The reliability indices were calculated on five different randomizations of the participants and were corrected with the Spearman–Brown formula. The mean correlation coefficients between the two subgroups were all positive and significant, ranging from .83 at age 7 to .94 at age 11 for emotional valence (n = 720), and from .67 at age 7 to .81 at age 13 for the arousal affective dimension (n = 720). It is also worth noting that, although we found high interrater reliabilities for both valence and arousal for the four age groups, word assessments seemed to be more consensual on the positive–negative continuum than on the calm–excited continuum. These findings are in line with previous ones (e.g., Hinojosa et al., 2016; Montefinese et al., 2014; Moors et al., 2013).

Tables 2 and 3 give Pearson correlations between the evaluations of children and adolescents for both the valence and arousal dimensions. Valence scores were positively correlated across age groups (all rs ≥ .81, n = 720, p < .005, Bonferroni corrected) and sexes (all rs ≥ .62, n = 720, p < .005, Bonferroni corrected). The same held for the arousal scores, though the correlations were slightly weaker than for valence.

Consistency of the present and previous ratings

To further test the generalizability of our ratings, we compared them with those collected from children in our previous study (Syssau & Monnier, 2009). The present study’s corpus included 565 words from that previous work. The comparison focused on the ratings shared by the two studies—that is, valence ratings collected from 7- and 9-year-old children. We obtained significant Pearson correlations between the words tested in both studies at ages 7 and 9, rs = .79 and .83, respectively, n = 565, ps < .001. The similarities between our present results and our previous ones suggest that the words elicited similar emotional reactions, despite the use of different scales to assess the valence dimension.

Age- and sex-related differences in valence and arousal ratings

To compare valence ratings across both ages and sexes, we ran a multiple regression analysis with mean valence ratings as the dependent variable and age and sex as the independent variables. This analysis was performed by items (i.e., words), but not by subjects. Two age groups were created by collapsing the data. The two groups consisted of 7-/9- and 11-/13-year-olds. The model yielded significant results [F(2, 5757) = 56.85, p < .001] and explained 2 % of the variance of the valence ratings. The regression analysis revealed that age was significantly related to the valence ratings (β age = –.14, p = .001), which decreased between 7/9 and 11/13 years of age. We found no relation between sex and the valence ratings (β sex = .00, n.s.). Thus, boys and girls do not seem to differ in the ways they judge words on the valence dimension.

We also performed a multiple regression analysis to examine the association between our mean arousal ratings (dependent variable) and both age and sex (independent variables). As previously, the analysis was item-based, with two age groups, 7-/9-year-olds and 11-/13-year-olds. A significant regression equation was found [F(2, 5757) = 32.54, p < .001], with an R 2 of .011. Both age and sex were significant predictors of the mean arousal ratings (β age = –.06, p < .001; β sex = –.09, p < .001). On the one hand, 7- and 9-year-olds gave higher mean arousal scores than did 11- and 13-year-olds. On the other hand, boys reported feeling more excited than girls. In sum, the comparisons of both the valence and arousal ratings across ages and sexes revealed significant differences. Younger participants were more positive in their valence ratings and more extreme in their arousal ratings than older children and adolescents. Furthermore, boys produced higher arousal ratings than girls.

The relationship between valence and arousal ratings

Figure 3 shows the location of each word in a two-dimensional affective space defined by the mean valence and mean arousal ratings of each word for the four age groups. Figure 4 shows the location of each word in the affective space for boys and girls, collapsed across age groups. To examine the relationship between the valence and arousal dimensions and to test whether age and/or sex influenced this relationship, we carried out a multiple regression analysis with mean arousal ratings as the dependent variable. The arousal variable was regressed on the linear term of valence, the quadratic term of valence, age, sex, the linear term of valence by age interaction, the quadratic term of valence by age interaction, the linear term of valence by sex interaction, and the quadratic term of valence by sex interaction. As we had done previously, this analysis was item-based, and two age groups, 7-/9- and 11-/13-year-olds, were created by collapsing the data. The proposed model yielded significant results [F(8, 5751) = 708.48, p < .001], explaining 50 % of the variance of the arousal ratings (see Table 4 for a summary of the multiple regression statistics). The quadratic relationship between arousal and valence was significant (β 2 val = .24, p < .001) and outperformed the linear relationship (∆R 2 = .06, p < .001). Concerning the variability of this relationship with age, the regression analysis revealed that the valence-squared by age interaction was nonsignificant (β 2 Age×Val = –.003, n.s.). The quadratic relationship between valence and arousal thus did not differ between age groups. Finally, the interaction with sex was significant (β 2 Sex×Val = –.07, p < .001), suggesting that the sex variable influences the quadratic relationship between arousal and valence. As is suggested in Fig. 4, we can conclude that girls rated both neutral and positive words as less arousing than did boys, whereas they rated negative words as more arousing.

Discussion

The objective of this work was to provide French researchers with valence and arousal norms for a large corpus of words rated by children and adolescents (aged 7, 9, 11, and 13 years) as a function of sex. To do this, we asked participants in these four age groups to evaluate, using the paper-and-pencil version of the SAM (Lang, 1980), the valence and arousal of 720 words acquired by the age of 7 years. The resulting data were used to develop the FANchild database. The norms that we collected are reliable and consistent with those obtained in our previous work (Syssau & Monnier, 2009). Therefore, they are suitable for use in the selection of words for future affective research.

The distribution of the 720 French words in the affective space was similar to the typical U shape found in other studies (e.g., McManis et al., 2001) and did not vary with age. The finding that words rated as highly pleasant or highly unpleasant are also rated as more arousing, and that words rated as neutral are rated as less arousing, is classic in the literature on adults (Eilola & Havelka, 2010; Redondo et al., 2007; Soares et al., 2012; Võ et al., 2009). Studies on children have generally used pictures (i.e., photographs) instead of words. McManis, Bradley, Berg, Cuthbert, and Lang (2001, Exp. 1, n = 60 pictures) and Sharp, van Goozen, and Goodyer (2006, n = 27 pictures) asked children aged between 7 and 11 years to evaluate pictures selected from the IAPS (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008). On the basis of the children’s ratings, these authors reported a quadratic relation between valence and arousal. On the other hand, whereas McManis et al. reported that the valence and arousal dimensions were linearly independent for children, Sharp et al. found, as we did in the present study, that the relationship between valence and arousal ratings was both linear and quadratic, with the quadratic model outperforming the linear one. Moreover, the present study provided no evidence for age-related changes in the affective space across childhood. Unfortunately, this issue has not been statistically tested in previous studies on children. However, at the other end of the life continuum, Keil and Freund (2009) provided evidence of a modulation of the relationship between valence and arousal by age. The authors asked young, middle-aged, and older participants to evaluate the valence and arousal dimensions of 90 German verbs. They found that the relationship between valence and arousal ratings was clearly quadratic for young adults (the linear model being nonsignificant), and that both quadratic and linear relations were observed for the middle-aged and older groups, whereas the linear relation accounted for less of the variance than did the quadratic relation (see Backs, da Silva, & Han, 2005, for similar results with pictures). Before providing a more definitive conclusion about the way valence and arousal ratings are related across childhood and adolescence, this relation should be further explored by including ratings from other age groups and a more extended corpus. Indeed, our corpus contained few negative words (i.e., 47 negative words at age 7, 70 at age 9, 71 at age 11, and 66 at age 13 when a criterion of mean valence ratings <4 was adopted). As we mentioned above, our 720-word corpus was selected from the FAN emotional database on the basis of age of acquisition (<7), and recent evidence has suggested that words learned early in life are perceived as more positive, whereas words acquired later are perceived as more negative (e.g., Bonin, Méot, et al., 2003; Citron, Weekes, & Ferstl, 2009; Moors et al., 2013).

The present study revealed rating similarities between the age groups. We observed a general consensus among age groups on which words were considered more positive or more negative and on which words were slightly, moderately, or highly arousing. However, despite a significant level of consensus, comparing the child and adolescent evaluations revealed age differences in both valence and arousal ratings: The 7- and 9-year-old children gave higher mean valence and arousal ratings than the other age groups. Moreover, the tendency to judge words positively (i.e., positive bias) decreased with age. The age-related differences we observed may be explained by changes in the ways children and adolescents perceived and/or used the valence and arousal scales. But these differences could also be considered in the perspective of conceptual act theory, which defines emotions as situated conceptualizations (Barrett, Wilson-Mendenhall, & Barsalou, 2015). According to this framework, the experiences evoked by words are assumed to vary with age. For instance, in this study, the word “train” was rated more positively by 7-years-olds than by 13-years-olds because, at age 7, “train” is likely associated with “game” rather than “transport experiences.” In any case, the examination of such potential age-related differences underlines the usefulness of providing age-specific normative data, taking into account the specific experiences evoked by words at any age.

As is evidenced by the correlations we observed, this study also revealed that a significant level of consensus exists in both valence and arousal ratings between boys and girls at any age. Boys and girls in the four age groups agreed on whether one word was more positive or more negative than another, and upon which words were slightly, moderately, or highly arousing. In the same vein, the multiple regression analysis showed that valence judgments did not vary according to sex. This finding contrasts with previous studies with children. Vasa et al. (2006) found that 9- to 11-year-olds girls gave more extreme valence judgments than did boys for both negative and positive words in a study using words. McManis et al. (2001, Exp. 2) observed a similar pattern of results for 7- to 10-year-old children in a study using pictures. Sharp et al. (2006), whose participants were children between 7 and 10 years old, found sex-related differences when using negative pictures. Our finding also contrasts with recent studies on adults. Both Hinojosa et al. (2016) and Montefinese et al. (2014) found that mean valence ratings were significantly higher for men than for women. Despite this apparent consensus on valence ratings, sex-related mean differences were evident for the arousal dimension. Boys rated words as more arousing than did girls. This result deserves further investigation, since it contrasts with previous ones. In fact, both McManis et al. and Sharp et al. reported no effect of sex on 7- to 11-year-old children’s arousal ratings of pictures, and the literature on adults classically reports no effect of sex (e.g., Hinojosa et al., 2016; Redondo et al., 2007) or more extreme arousal ratings by women than by men (e.g., Montefinese et al., 2014; Söderholm, Häyry, Laine, & Karrasch, 2013)—that is, the opposite of what we found. Finally, sex-related differences also appeared when we examined the relationship between valence and arousal ratings. The finding that sex influenced the relationship between valence and arousal is consistent with a previous study by Riegel et al. (2015) with adult participants. Riegel et al. reported that women rated neutral and positive words as less arousing than did men, but they rated negative words as more arousing (i.e., a similar pattern to the one we found). To sum up, the sex effects we observed in this study are not always consistent with previous reports; as such, they deserve further investigation. Nonetheless, providing valence and arousal ratings for boys and girls separately will allow researchers to take into account sex differences when selecting their experimental materials.

Conclusion

The present work goes further than our previous French-language study of children’s emotional ratings (Syssau & Monnier, 2009), in two main ways. First, we obtained ratings for both arousal and valence; future French studies with children and adolescents will therefore be able to select emotional words on the basis of both dimensions. Second, we obtained ratings from both children and adolescents, thereby extending the developmental period for which emotional data are available. In line with McManis et al. (2001), our study confirms that, from the age of 7 years on, children are able to use the pictorial 9-point SAM scale to rate words on the valence and arousal dimensions. Despite the significant correlations between the four age groups’ ratings (i.e., age 7, age 9, age 11, and age 13), we also found age-related differences. These differences show that the emotional perception of words may change with age. Therefore, it is important to systematically check that the emotional words selected for a study are suited to the ages of the participants.

In future work, we plan to expand the FANchild database to include a larger number of words, particularly negative words (when the mean valence ratings were averaged across all participants, only 7.4 % of the words were rated below the value of 4 on the valence scale).

In addition, it would be desirable to include ratings from other age groups between the age of 13 years and adulthood. Obtaining valence and arousal evaluations for different periods of human development would allow researchers to compare populations with emotional disorders. The FANchild database could also be extended to older adults, as emotional evaluations of words change throughout life.

To conclude, we hope that the FANchild database will enable researchers to use emotional words suited to the ages and the sexes of their studies’ participants, and to more reliably investigate the development of the relationship between emotion and cognition.

References

Alario, F.-X., & Ferrand, L. (1999). A set of 400 pictures standardized for French: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, and age of acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 531–552. doi:10.3758/BF03200732

Backs, R. W., da Silva, S. P., & Han, K. (2005). A comparison of younger and older adults’ Self-Assessment Manikin ratings of affective pictures. Experimental Aging Research, 31, 421–440. doi:10.1080/03610730500206808

Barrett, L. F., Wilson-Mendenhall, C. D., & Barsalou, L. W. (2015). The conceptual act theory: A roadmap. In L. F. Barrett & J. A. Russell (Eds.), The psychological construction of emotion (pp. 83–110). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Aubert, L., Malardier, N., Niedenthal, P., & Capelle-Toczek, M.-C. (2003). Normes de concrétude, de valeur d’imagerie, de fréquence subjective et de valence émotionnelle pour 866 mots. L'Année Psychologique, 104, 655–694. doi:10.3406/psy.2003.29658

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Ferrand, L., & Roux, S. (2011). L’imageabilité: Normes et relations avec d’autres variables psycholinguistiques. L'Année Psychologique, 111, 327–357. doi:10.4074/S0003503311002041

Bonin, P., Peereman, R., Malardier, N., Méot, A., & Chalard, M. (2003). A new set of 299 pictures for psycholinguistic studies: French norms for name agreement, image agreement, conceptual familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, age of acquisition, and naming latencies. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 158–167. doi:10.3758/BF03195507

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affective norms for English words (ANEW): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida.

Brainerd, C. J., Holliday, R. E., Reyna, V. F., Yang, Y., & Toglia, M. P. (2010). Developmental reversals in false memory: Effects of emotional valence and arousal. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 107, 137–154. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.013

Citron, F., Weekes, B., & Ferstl, E. (2009). Evaluation of lexical and semantic features for English emotion words. In K. Alter, M. Horle, M. Lindgren, M. Roll, & J. von Koss Torkildsen (Eds.), Brain talk: Discourse with and in the brain (pp. 11–20). Lund, Sweden: Media-Tryck.

Cohen-Gilbert, J. E., & Thomas, K. M. (2013). Inhibitory control during emotional distraction across adolescence and early adulthood. Child Development, 84, 1954–1966. doi:10.1111/cdev.12085

Desrochers, A., & Bergeron, M. (2000). Valeurs de fréquence subjective et d’imagerie pour un échantillon de 1,916 substantifs de la langue française. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54, 274–325. doi:10.1037/h0087347

Dresler, T., Mériau, K., Heekeren, H. R., & van der Meer, E. (2009). Emotional Stroop task: Effect of word arousal and subject anxiety on emotional interference. Psychological Research, 73, 364–371. doi:10.1007/s00426-008-0154-6

Eilola, T. M., & Havelka, J. (2010). Affective norms for 210 British English and Finnish nouns. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 134–140. doi:10.3758/BRM.42.1.134

Ferrand, L., Grainger, J., & New, B. (2003). Normes d’âge d’acquisition pour 400 mots monosyllabiques [Age-of-acquisition norms for 400 monosyllabic French words]. L'Année Psychologique, 103, 445–467. doi:10.3406/psy.2003.29645

Gilet, A. L., Grühn, D. D., Studer, J. J., & Labouvie-Vief, G. G. (2012). Valence, arousal, and imagery ratings for 835 French attributes by young, middle-aged, and older adults: The French Emotional Evaluation List (FEEL). European Review of Applied Psychology, 62, 173–181. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2012.03.003

Gonthier, I., Desrochers, A., Thompson, G., & Landry, D. (2009). Normes d’imagerie et de fréquence subjective pour 1 760 mots monosyllabiques de la langue française. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63, 139–149. doi:10.1037/a0015386

Grühn, D., & Smith, J. (2008). Characteristics for 200 words rated by young and older adults: Age-dependent evaluations of German adjectives (AGE). Behavior Research Methods, 40, 1088–1097. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.4.1088

Heim, S., Ihssen, N., Hasselhorn, M., & Keil, A. (2013). Early adolescents show sustained susceptibility to cognitive interference by emotional distractors. Cognition and Emotion, 27, 696–706. doi:10.1080/02699931.2012.736366

Hinojosa, J. A., Martίnez-Garcίa, N., Villalba-Garcίa, C., Fernández-Folgueiras, U., Sánchez-Carmona, A., Pozo, M. A., & Montoro, P. R. (2016). Affective norms of 875 Spanish words for five discrete emotional categories and two emotional dimensions. Behavior Research Methods, 48, 272–284. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0572-5

Ho, S. M. Y., Mak, C. W. Y., Yeung, D., Duan, W., Tang, S., Yeung, J. C., & Ching, R. (2015). Emotional valence, arousal, and threat ratings of 160 Chinese words among adolescents. PLoS ONE, 10, e132294. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132294

Howe, M. L., Candel, I., Otgaar, H., Malone, C., & Wimmer, M. C. (2010). Valence and the development of immediate and long-term false memory illusions. Memory, 18, 58–75. doi:10.1080/09658210903476514

Keil, A., & Freund, A. M. (2009). Changes in the sensitivity to appetitive and aversive arousal across adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 24, 668–680. doi:10.1037/a0016969

Kensinger, E. A., Brierley, B., Medford, N., Growdon, J. H., & Corkin, S. (2002). Effects of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease on emotional memory. Emotion, 2, 118–134. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.2.2.118

Korfine, L., & Hooley, J. M. (2000). Directed forgetting of emotional stimuli in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 214–221. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.214

Kotta, I., & Szamosközi, Ş. (2012). Affective reactions to images in anxious children. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 12, 49–62.

Koven, N. S., Heller, W., Banich, M. T., & Miller, G. A. (2003). Relationships of distinct affective dimensions to performance on an emotional Stroop task. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 671–680. doi:10.1023/A:1026303828675

Kuchinke, L., Võ, M. L., Hofmann, M., & Jacobs, A. M. (2007). Pupillary responses during lexical decisions vary with word frequency but not emotional valence. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 65, 132–140. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.04.004

Lachaud, C. M. (2007). CHACQFAM: Une base de données renseignant l’âge d’acquisition estimé et la familiarité pour 1225 mots monosyllabiques et bisyllabiques du français [CHACQFAM: A lexical data base for the estimated age of acquisition and familiarity of 1225 monosyllabic and bisyllabic French words]. L'Année Psychologique, 107, 39–63. doi:10.4074/S0003503307001030

Lang, P. J. (1980). Behavioral treatment and bio-behavioral assessment: Computer applications. In J. B. Sidowski, J. H. Johnson, & T. A. William (Eds.), Technology in mental health care delivery systems (pp. 119–137). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual (Technical Report No. A-8). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology.

Lété, B., Sprenger-Charolles, L., & Colé, P. (2004). MANULEX: A grade-level lexical database from French elementary school readers. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 156–166. doi:10.3758/BF03195560

Majerus, S., & D’Argembeau, A. (2011). Verbal short-term memory reflects the organization of long-term memory: Further evidence from short-term memory for emotional words. Journal of Memory and Language, 64, 181–197. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2010.10.003

Mancini, G., Agnoli, S., Baldaro, B., Ricci Bitti, P. E., & Surcinelli, P. (2013). Facial expressions of emotions: Recognition accuracy and affective reactions during late childhood. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 147, 599–617. doi:10.1080/00223980.2012.727891

McManis, M. H., Bradley, M. M., Berg, W. K., Cuthbert, B. N., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotional reactions in children: Verbal, physiological, and behavioral responses to affective pictures. Psychophysiology, 38, 222–231. doi:10.1017/S0048577201991140

Minnema, M. T., & Knowlton, B. J. (2008). Directed forgetting of emotional words. Emotion, 8, 643–652. doi:10.1037/a0013441

Monnier, C., & Syssau, A. (2008). Semantic contribution to verbal short-term memory: Are pleasant words easier to remember than neutral words in serial recall and serial recognition? Memory & Cognition, 36, 35–42. doi:10.3758/MC.36.1.35

Monnier, C., & Syssau, A. (2014). Affective norms for French words (FAN). Behavior Research Methods, 46, 1128–1137. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0431-1

Montefinese, M., Ambrosini, E., Fairfield, B., & Mammarella, N. (2014). The adaptation of the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) for Italian. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 887–903. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0405-3

Moors, A., De Houwer, J., Hermans, D., Wanmaker, S., van Schie, K., Van Harmelen, A. L., … Brysbaert, M. (2013). Norms of valence, arousal, dominance, and age of acquisition for 4,300 Dutch words. Behavior Research Methods, 45, 169–177. doi:10.3758/s13428-012-0243-8

Moradi, A. R., Taghavi, R., Neshat-Doost, H. T., Yule, W., & Dalgleish, T. (2000). Memory bias for emotional information in children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 14, 521–534. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00037-2

Neshat-Doost, H. T., Moradi, A. R., Taghavi, M. R., Yule, W., & Dalgleish, T. (2000). Lack of attentional bias for emotional information in clinically depressed children and adolescents on the dot probe task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 363–368. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00620

New, B., Pallier, C., Brysbaert, M., & Ferrand, L. (2004). Lexique 2: A new French lexical database. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 516–524. doi:10.3758/BF03195598

Niedenthal, P. M., Auxiette, C., Nugier, A., Dalle, N., Bonin, P., & Fayol, M. (2004). A prototype analysis of the French category “émotion”. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 289–312. doi:10.1080/02699930341000086

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Redondo, J., Fraga, I., Padrón, I., & Comesaña, M. (2007). The Spanish adaptation of ANEW (Affective Norms for English Words). Behavior Research Methods, 39, 600–605. doi:10.3758/BF03193031

Riegel, M., Wierzba, M., Wypych, M., Żurawski, Ł., Jednoróg, K., Grabowska, A., & Marchewka, A. (2015). Nencki affective word list (NAWL): The cultural adaptation of the Berlin affective word list–reloaded (BAWL-R) for Polish. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 1222–1236. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0552-1

Sharp, C., Van Goozen, S., & Goodyer, I. (2006). Children’s subjective emotional reactivity to affective pictures: Gender differences and their antisocial correlates in an unselected sample of 7–11-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 143–150. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01464.x

Soares, A., Comesaña, M., Pinheiro, A. P., Simões, A., & Frade, C. (2012). The adaptation of the Affective Norms for English words (ANEW) for European Portuguese. Behavior Research Methods, 44, 256–269. doi:10.3758/s13428-011-0131-7

Söderholm, C., Häyry, E., Laine, M., & Karrasch, M. (2013). Valence and arousal ratings for 420 Finnish nouns by age and gender. PLoS ONE, 8, e72859. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072859

Stevenson, R. A., Mikels, J. A., & James, T. W. (2007). Characterization of the Affective Norms for English Words by discrete emotional categories. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 1020–1024. doi:10.3758/BF03192999

Syssau, A., & Laxén, J. (2012). L’influence de la richesse sémantique dans la reconnaissance visuelle des mots émotionnels. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66, 70–78. doi:10.1037/a0027083

Syssau, A., & Monnier, C. (2009). Children’s emotional norms for 600 French words. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 213–219. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.1.213

Syssau, A., & Monnier, C. (2012). L’influence de la valence émotionnelle positive des mots sur la mémoire des enfants [The influence of the emotional positive valence of words on children memory]. Psychologie Française, 57, 237–250. doi:10.1016/j.psfr.2012.09.003

Tse, C., & Altarriba, J. (2009). The word concreteness effect occurs for positive, but not negative, emotion words in immediate serial recall. British Journal of Psychology, 100, 91–109. doi:10.1348/000712608X318617

Van Bergen, P., Wall, J., & Salmon, K. (2015). The good, the bad, and the neutral: The influence of emotional valence on young children’s recall. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4, 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.11.001

Vasa, R. A., Carlino, A. R., London, K., & Min, C. (2006). Valence ratings of emotional and non-emotional words in children. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 1169–1180. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.025

Võ, M. L.-H., Conrad, M., Kuchinke, L., Urton, K., Hofmann, M. J., & Jacobs, A. M. (2009). The Berlin affective word list reloaded (BAWL–R). Behavior Research Methods, 41, 534–538. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.2.534

Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 45, 1191–1207. doi:10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x

Windmann, S., Daum, I., & Güntiürkün, O. (2002). Dissociating prelexical and postlexical processing of affective information in the two hemispheres: Effects of the stimulus presentation format. Brain and Language, 80, 269–286. doi:10.1006/brln.2001.2586

Author note

The authors are grateful to the children and adolescents who participated in the study, and to their teachers for their cooperation. We thank Lisa Auvray, Julie Bégora, Margaux Bougier, Mégane Brenot, Marie-Frédérique Buy, Eva Engheben, Marine Fournel, Agnès Furlan, Nadège Maffre, Aurélie Sala, and Raphaëlle Scappaticci for their valuable assistance in recruiting the participants and collecting the data. We also thank our colleague Yannick Stephan for his help with the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monnier, C., Syssau, A. Affective norms for 720 French words rated by children and adolescents (FANchild). Behav Res 49, 1882–1893 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0831-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0831-0