Abstract

The most important forms of idioms in Chinese, chengyus (CYs), have a fixed length of four Chinese characters. Most CYs are joined structures of two, two-character words—subject–verb units (SVs), verb–object units (VOs), structures of modification (SMs), or verb–verb units—or of four, one-character words. Both the first and second pairs of words in a four-word CY form an SV, a VO, or an SM. In the present study, normative measures were obtained for knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, age of acquisition, predictability, literality, and compositionality for 350 CYs, and the influences of the CYs’ syntactic structures on the descriptive norms were analyzed. Consistent with previous studies, all of the norms yielded a high reliability, and there were strong correlations between knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, and age of acquisition, and between familiarity and predictability. Unlike in previous studies (e.g., Libben & Titone in Memory & Cognition, 36, 1103–1121, 2008), however, we observed a strong correlation between literality and compositionality. In general, the results seem to support a hybrid view of idiom representation and comprehension. According to the evaluation scores, we further concluded that CYs consisting of just one SM are less likely to be decomposable than those with a VOVO composition, and also less likely to be recognized through their constituent words, or to be familiar to, known by, or encountered by users. CYs with an SMSM composition are less likely than VOVO CYs to be decomposable or to be known or encountered by users. Experimental studies should investigate how a CY’s syntactic structure influences its representation and comprehension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idioms are fixed expressions that are standardized in meaning and form. Some idioms (e.g., easy on the eyes) can be understood directly through the constituent words, but the overall meanings of other idioms (e.g., red herring) seem to have nothing to do with the conventional meanings of the words of which they are composed. Therefore, differences seem to exist among idioms in terms of how they are represented and how they are understood. Indeed, several theories have been proposed on this point. For example, idioms can be treated like complex words and be represented and understood as whole units (e.g., kick the bucket; see, e.g., Swinney & Cutler, 1979). It is also argued that an idiom can receive different weights of contributions in representation from its constituent words (e.g., Gibbs & Nayak, 1989) and cannot be understood without the semantic relations between its constituent words being processed (e.g., pop the question; e.g., Gibbs, Nayak, & Cutting, 1989).

Recently, a hybrid view has begun to be well recognized; this theory assumes that idioms are both compositional and noncompositional. According to Cutting and Bock (1997), an idiom has its own representation of the lexical concept as a whole, the activation of which spreads to the representations for the constituent words at the lexical–syntactic (lemma) level. Sprenger, Levelt, and Kempen (2006) extended this theory, arguing that there are superlemmas between the representations for idioms as whole units and those for the constituent words. As separate representations for the syntactic properties of idioms, superlemmas are connected to the idioms’ building blocks. As far as idiom comprehension is concerned, those that are predictable or familiar to the users are processed as whole units, but those that are not predictable or are unfamiliar to the users may have to be compositionally analyzed before being understood (Cacciari & Tabossi, 1988; Titone & Connine, 1999).

In fact, the characteristics of idioms, such as how familiar they are to the users and whether they are decomposable, seem to pertain to the development of theories of idiom representation and comprehension. It is even believed that norms such as those for the familiarity and compositionality of idioms could potentially be helpful for experimental studies into the cognitive mechanisms of how idiomatic expressions are represented and comprehended (see Bonin, Méot, & Bugaiska, 2013, for a review), and several reports are available in this line of research (e.g., Bonin et al., 2013; Tabossi, Arduino, & Fanari, 2011), in which the users’ knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, and age of acquisition (AoA) of idioms, and the idioms’ predictability, literality, and compositionality, are among the most important variables. By knowledge, we mean the degree to which the users think they know the overall meaning of an idiom and can verbally explain it (Tabossi et al., 2011). The more familiar a speaker is with an idiom, the more likely that he or she obtains access to its overall meaning via direct lookup (Cronk & Schweigert, 1992). The subjective frequency of an idiom refers to how often users encounter it in everyday life (Bonin et al., 2013), and the AoA of an idiom is the age at which the users acquired it. By predictability, we mean the extent to which the users can complete an incomplete idiom, and by literality, we mean the degree to which the users think an idiom can be understood just through the literal meanings of its constituent words. The overall meanings of idioms of high predictability are retrieved more quickly than those of low predictability (Cacciari & Tabossi, 1988). Because the processing of linguistic information is obligatory (Miller & Johnson-Laird, 1976, as cited in Bonin et al., 2013), the literal meanings of an idiom’s constituent words cannot be avoided. Compositionality refers to the degree to which the users think an idiom’s overall meaning is composed of the meanings of its individual components. Decomposable idioms are different from noncompositional idioms in being understood by both children (Caillies & Le Sourn-Bissaoui, 2008) and adults (Caillies & Butcher, 2007).

For example, Tabossi et al. (2011) required 740 Italian speakers (ranging from 17 to 50 years in age) to participate in a study, and obtained descriptive norms for length, knowledge, familiarity, AoA, predictability, syntactic flexibility (the degree to which an idiom can be syntactically changed but still retain its overall meaning), literality, and compositionality for 245 idioms in Italian. By descriptive norms, we mean descriptive statistics for the idioms’ features, obtained by means of objective measurements. Tabossi et al.’s discussions on the descriptive statistics of and the correlations between the variables are of significant value to empirical studies on Italian idioms. By collecting descriptive norms for knowledge, predictability, literality, compositionality, subjective and objective frequency, familiarity, AoA, and length for 305 French idioms, and measuring the comprehension times for these idioms, Bonin et al. (2013) demonstrated the rich relevance of norms for psycholinguistic studies on idiomatic expressions in French. Libben and Titone (2008) used both offline and online measures to analyze the normative characteristics of 219 English idioms. They found that high familiarity is associated with good comprehension, and that decomposability only plays a limited role in the early stages of idiom comprehension.

Each language has a large repertoire of idiomatic expressions (Cacciari & Tabossi, 1988). To the authors’ knowledge, however, few normative studies have reported on idioms in languages other than English (e.g., Cronk, Susan, Lima, & Schweigert, 1993; Libben & Titone, 2008; Titone & Connine, 1994b), French (e.g., Bonin et al., 2013; Caillies, 2009), and Italian (e.g., Tabossi et al., 2011). The present study was performed to provide a normative description of Chinese idioms.

Unlike alphabetic languages, written Chinese has a logographic script in which the basic units are characters. Although many characters are words on their own, most can join with one or more than one character, to form two-character words or words of more than two characters. Actually, more than 70 % of the 50,000 most frequently used words are two characters long (State Language Affairs Committee, 2008), and over 95 % of Chinese idioms are of four characters (Liu & Cheung, 2014). These four-character idioms are referred to as chengyus (CYs, hereafter).

One prominent feature of CYs is their fixed syntactic structures (Zhou, 2004). In 90 % of cases, a CY has a syntactic structure of two, two-character words—a noun followed by a verb to form a subject–verb unit (SV; e.g.,  , river Jing and river Wei–not separate), a verb followed by a noun to form a verb–object unit (VO; e.g.,

, river Jing and river Wei–not separate), a verb followed by a noun to form a verb–object unit (VO; e.g.,  , gradually enter into–a perfect condition), an adjective followed by a noun or an adverb followed by a verb to form a structure of modification (SM; e.g.,

, gradually enter into–a perfect condition), an adjective followed by a noun or an adverb followed by a verb to form a structure of modification (SM; e.g.,  , luxuriantly–become a common practice), or a verb–verb unit (VV; e.g.,

, luxuriantly–become a common practice), or a verb–verb unit (VV; e.g.,  , accumulate labor–cause illness)—or of four one-character words. Both the first and second pairs of words in a four-word CY form an SV (e.g.,

, accumulate labor–cause illness)—or of four one-character words. Both the first and second pairs of words in a four-word CY form an SV (e.g.,  , language–simple–meaning–thoughtful), a VO (e.g.,

, language–simple–meaning–thoughtful), a VO (e.g.,  , help–those in danger–aid–those in peril), or an SM (e.g.,

, help–those in danger–aid–those in peril), or an SM (e.g.,  , genuine–talent–sturdy–knowledge). Since an idiom’s syntactic structure plays a significant role in how it is represented and understood (Holsinger, 2013; Konopka & Bock, 2009; Robert, Curt, Gary, & Kathleen, 2001), an investigation into the relationship between CYs’ syntactic structures and their descriptive norms will be helpful to provide indications of CYs’ representation and comprehension. For example, are four-word CYs similar to two-word CYs in their correlations between the seven features? In what way are SM CYs different from SV CYs in literality? Answers to such questions can inspire a new understanding of how idioms are represented in general and can be of significant value to the designs of experimental studies into the mechanisms of idioms’ representation and comprehension.

, genuine–talent–sturdy–knowledge). Since an idiom’s syntactic structure plays a significant role in how it is represented and understood (Holsinger, 2013; Konopka & Bock, 2009; Robert, Curt, Gary, & Kathleen, 2001), an investigation into the relationship between CYs’ syntactic structures and their descriptive norms will be helpful to provide indications of CYs’ representation and comprehension. For example, are four-word CYs similar to two-word CYs in their correlations between the seven features? In what way are SM CYs different from SV CYs in literality? Answers to such questions can inspire a new understanding of how idioms are represented in general and can be of significant value to the designs of experimental studies into the mechanisms of idioms’ representation and comprehension.

Method

Participants

The participants were 735 college students (385 males, 350 females; M age = 18.9 years, age range 18.2–20.3 years), who were recruited on campus by means of a flyer advertisement at a university in mainland China.

Materials and procedure

Inspired by Bonin et al. (2013), we recorded each measurement on a 7-point Likert scale. First, we roughly excluded those that might be unfamiliar to the participants from the 4,227 CYs in the Normal Dictionary of Chinese Chengyu with Full Function (Chen, 2009; one of the most popular dictionaries of CYs in the country) that are SV, SM, VO, VV, SVSV, SMSM, or VOVO in structure. The CYs were divided into 39 groups at random. Ten college students were then required to evaluate the familiarity of the idioms in each group on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = unfamiliar, 2 = familiar, 3 = very familiar). These students did not take part in the follow-up surveys. From the 3,694 CYs that had an average score of 2 or higher, 50 were selected at random for each of the seven syntactic structures.

Then, the 350 CYs were mixed at random and divided into five equal groups. The CYs chosen for each of the groups can be found in the Appendix. Each group was printed on a sheet of paper in two columns with seven numbers ([1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], and [7]) at the right side of each CY. The instructions were printed at the top of the page. For each CY to be evaluated from the seven categories, the 735 participants were divided into 35 equal groups at random, and every one-piece-of-paper questionnaire was delivered to a group of students, who were required to make an evaluation response to each CY according to the instructions by putting a tick in one of the seven numbers. Table 1 summarizes the instructions for the seven kinds of surveys.

Results and discussion

The norms

The descriptive statistics of the participants’ responses on each questionnaire and the corresponding scores for reliability are displayed in Table 2.

As is shown in Table 2, all of the norms yielded a reliability score over .94. As in Bonin et al. (2013), the compositionality and AoA norms had the highest and lowest reliabilities, respectively. Moreover, the reliability score for the AoA norm was still very high (α = .941). Probably because the age range was wide for their participants, Tabossi et al. (2011) found that the AoA norm was significantly less reliable than their other norms. On the contrary, the high reliability scores across the seven scales in the present study seem to suggest a high degree of consistency among the college-student participants in their evaluations of the CYs.

The average evaluation scores for knowledge, familiarity, and predictability were quite high on the 7-point Likert scales. Furthermore, these three norms also had high absolute values of their skewness scores, suggesting that the participants were quite familiar with all the CYs, in agreement with Bonin et al. (2013). This was especially the case with the predictability norm (6.52 ± 0.57 [M ± SD]). That is, the last character of a CY was very easy for the participants to predict, partly because of the expressions’ fixed length of four characters. The low absolute values of the skewness scores suggest that the norms for literality, compositionality, and subjective frequency embrace symmetric distributions.

Correlations

The Pearson correlations between the scores of the participants’ responses to each questionnaire were calculated, and the results are displayed in Table 3.

As is indicated in Table 3, the seven variables were significantly correlated with one another, but the correlations did not seem to be of the same strength. First, as in Bonin et al. (2013), there were strong intercorrelations between the participants’ scores on knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, and AoA. That is, the earlier the participants acquired a CY, the more familiar they were with it, the more frequently they encountered it, and the more able they were to verbally explain it. Given that the effect of AoA is strong in tasks that require semantic code activation (e.g., Bonin, Barry, Méot, & Chalard, 2004; Bonin et al., 2013; Johnston & Barry, 2006), we further speculate that the users’ knowledge, familiarity, AoA, and subjective frequency of CYs might be strong indicators of semantic representations for CYs as wholes.

As in Titone and Connine (1994a) and Tabossi et al. (2011), the participants’ evaluation scores for familiarity were strongly correlated with those of predictability, suggesting that the more familiar they were with a CY, the more likely they were to be able to complete it if its last character was missing. Consistent with this, the CYs’ predictability was strongly correlated with the participants’ knowledge, AoA, and subjective frequency of the CYs. This finding seems to be in support of Sprenger et al.’s (2006) theory that superlemmas mediate the connections between the conceptual representations for idioms as wholes and those for the component words. In other words, the users’ familiarity and knowledge of CYs’ overall meanings activate the superlemmas, which in turn help retrieve the component words.

Second, the participants’ evaluation scores for literality were strongly correlated with those for compositionality, apparently contrary to the negative correlations between literality and compositionality in Libben and Titone (2008) and Bonin et al. (2013). In addition, Tabossi et al. (2011) found no correlation between literality and compositionality. The difference between the present study and the previous studies (Bonin et al., 2013; Libben & Titone, 2008; Tabossi et al., 2011) in terms of the correlations between literality and compositionality might be an indication of the specific nature of the Chinese written language. In Chinese, the meaning of an expression is more visually evident than in an alphabetic language (Zhang et al., 2013). The overall meaning of a CY is also likely to be induced through the meanings of its constituent words. Indeed, this result appears to be a piece of evidence in support of the superlemma theory, which predicts that the meanings of the constituent words predict production of the idiom (Sprenger et al., 2006).

Third, as in Tabossi et al. (2011), the participants’ evaluation scores for familiarity and knowledge were strongly correlated with those for literality, indicating that college students’ familiarity and knowledge of CYs are closely related to the literal meanings of the CYs’ constituent words. Consistent with this finding, the participants’ knowledge, AoA, and subjective frequency of CYs were significantly correlated with the CYs’ literality and compositionality. However, the participants’ evaluation scores for predictability were relatively weakly correlated with those for literality and compositionality. That is, compositionality and literality are not as strong predictors of a CY’s overall meaning as are knowledge, familiarity, AoA, and subjective frequency.

In addition, the factor analysis revealed two main components, which accounted for 80.86 % of the variances. Knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, AoA, and predictability mainly loaded onto the first factor, accounting for 61.95 % of the variances, and compositionality and literality onto the second factor, accounting for 18.12 % of the variances. Consistent with the discussions of the correlations, the first factor seem to reflect the participants’ awareness of the CYs’ noncompositional features, and the second factor their consciousness of the CYs’ compositional characteristics.

The CYs’ syntactic structures

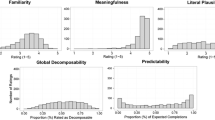

Statistics from one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) of the participants’ evaluation scores for the seven norms are shown in Table 4, with the CYs’ differences in syntactic structure as the single variable. As is illustrated in Fig. 1, diversity existed between the scores for knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, literality, and compositionality under the influences of the CYs’ syntactic structures. Post-hoc least significant difference tests revealed significance differences between the CYs with different structures for each of the five norms (see Table 5).

Knowledge

The CYs with an SM structure were significantly lower than VOVO CYs, and SMSM CYs were as well, in the evaluation scores for knowledge, suggesting that college students are more confident of knowing the meaning of and being able to verbally explain CYs with a VOVO composition than of doing either with SM or SMSM CYs.

Familiarity

In familiarity evaluation scores, the CYs with an SM structure were significantly lower than the CYs with VO, VV, VOVO, and SMSM structures; SV CYs were significantly lower than VO, VV, VOVO, and SMSM CYs; and SVSV CYs were significantly lower than VO and VV CYs. This suggests that CYs with SM and SV compositions are less familiar than those with VO, VV, VOVO, and SMSM structures, and that SVSV CYs are less familiar than those with VO and VV structures, to college students.

Subjective frequency

The CYs with SM and SV structures were significantly lower than those with a VO structure, and the CYs with an SMSM composition were significantly lower than those with VO, VV, and VOVO compositions in the evaluation scores for subjective frequency. These results mainly indicate that college students most frequently encounter VO CYs, and much less frequently encounter those with SM, SV, and SMSM structures in daily life.

Literality

The CYs with an SM structure were significantly lower than those with VO, VV, VOVO, SMSM, and SVSV structures, and the CYs with an SV composition were significantly lower than those with VOVO and SMSM compositions in evaluation scores for literality. This indicates that SM and SV CYs are more difficult to understand through the literal meanings of their component words in than are those with the other five structures, and that SM CYs seem even more so than SV CYs.

Compositionality

The CYs with an SM structure were significantly lower than those with VO, SV, VV, and VOVO structures, and VOVO CYs were significantly higher than those with VO, SV, SMSM, and SVSV structures in compositionality evaluation scores. This mainly suggests that SM CYs are the most difficult to decompose, and that those with a VOVO structure are the most decomposable.

Explanations

The participants’ evaluation scores for AoA and predictability both tended to remain the same for the CYs of different syntactic structures. However, the CYs’ syntactic structures had significant influences on the participants’ evaluation scores for knowledge, familiarity, subjective frequency, literality, and compositionality, which requires explanation.

The participants had low scores for SM CYs in each of the five norms. Users may have a low degree of familiarity and understanding and a low frequency of encounter with CYs having an SM composition, which are difficult to understand merely through their constituent words and are unlikely to be decomposed in meaning. In other words, an SM CY that is unfamiliar to, not known by, or not frequently encountered by a user is not easy to comprehend or is undecomposable. Similarly, CYs with an SMSM structure also seem less likely to be known or encountered by users and to be less decomposable than those with VOVO and VO structures. Unlike SM CYs, however, SMSM CYs may not be less familiar to users and may be more likely to be comprehended just through their constituent characters, in comparison with CYs with a VOVO or VO structure. The differences between CYs with SM and SMSM structures seem to suggest that literality and compositionality are not the same, and that familiarity is different from knowledge or subjective frequency in indicating CYs’ psycholinguistic characteristics.

CYs with an SV composition are less likely to be familiar to or encountered by users than are those with a VOVO or VO structure. Similar to SV CYs, in being less familiar to users than VOVO or VO CYs, SVSV CYs are dissimilar to their SV counterparts in not being less frequently encountered by users than VOVO or VO CYs. The difference between CYs with SV and SVSV compositions appears to indicate that familiarity is different from subjective frequency in nature.

Moreover, the changes in literality seem to have the same pattern as those in compositionality under the influence of CYs’ syntactic structures, except that those with an SMSM structure were not significantly different from VOVO CYs in literality evaluations, but had significantly lower scores than VOVO CYs in compositionality evaluations.

One might intuitively feel that there are overlaps between knowledge, familiarity, and subjective frequency, or between literality and compositionality. However, the present study seems to provide a strong piece of evidence that neither knowledge, familiarity, and subjective frequency nor literality and compositionality can be taken as being the same.

Implications

The normative statistics and the interactions between the norms and the CYs’ syntactic structures have significant implications for helping researchers do experimental studies into CYs’ representations and comprehension. The apparent difference between CYs and idioms in other languages (Bonin et al., 2013; Libben & Titone, 2008; Tabossi et al., 2011) in the correlations between literality and compositionality is in agreement with the findings of Zhang et al. (2013) that the meaning of an expression is more visually evident in Chinese than in an alphabetic language. Obviously, more research will be needed on the specific features of idioms in other languages than is available from the few languages in which normative studies have been conducted.

In the present study, the influence of patterns of CYs’ syntactic structures on CYs’ descriptive norms might indicate particular mechanisms for how CYs are represented and how they are comprehended. Liu, Li, Shu, Zhang, and Chen (2010); Zhang, Yang, Gu, and Ji (2013); and Liu and Cheung (2014) set good examples of experimental investigations into the cause-and-effect relation between CYs’ syntactic structures and CYs’ comprehension, but more work is needed in this line of research to help enhance the development of theories on idiom representation and idiom comprehension in general.

On the basis of the interactions between the five norms and the CYs’ syntactic structures (see Fig. 1), one may conduct a series of experimental studies to help specify the nature of the superlemmas between the representations for idioms as wholes and those for their constituent words (Sprenger et al., 2006). Theoretical differences could be made available between two- and four-word CYs, and comparisons could also be made between two-word CYs with different structures and between four-word CYs with different structures, regarding how the connections are mediated between the conceptual representations for idioms as wholes and those for the constituent words.

In cognitive tasks of idiom recognition with and without sentential contexts, for example, comparisons could be made between participants’ reaction times and/or event-related potentials to CYs with different syntactic structures, as are outlined in Table 6. Furthermore, regression analyses on participants’ online performance with the norms as predictors could also be very fruitful in reflecting the norms’ contributions to how the CYs of each syntactic structure are represented and/or comprehended.

Similarly, studies on the relations between the syntactic structures and normative features of idioms promise to yield interesting results in languages other than Chinese. Moreover, it seems to be clearly evidenced in the interactions between the syntactic structures and norms of the CYs (see Fig. 1) that familiarity is different from subjective frequency and that literality cannot be taken as being the same as compositionality. Both familiarity and subjective frequency and both literality and compositionality should be considered in normative studies of idioms, and probably in studies of words in general.

Conclusion

Our normative results for familiarity, knowledge, predictability, AoA, subjective frequency, literality, and compositionality among 350 CYs with seven structures (VO, SM, SV, VV, VOVO, SMSM, and SVSV) seemed to support the hybrid view of idiom representation and comprehension. The influence of the CYs’ syntactic structures on the descriptive norms did not have the same pattern for all variables. We concluded that CYs with an SM composition are less likely than VOVO CYs to be decomposable, to be recognized through their constituent words, or to be familiar to, known by, or encountered by users. CYs with an SMSM structure are also less likely than VOVO CYs to be decomposable or to be known or encountered by users. The present study provides an outline of how CYs’ characteristics are intercorrelated and how their features interact with their syntactic structures, which can be used as a reference for further studies on idioms in Chinese. Empirical studies can investigate how the syntactic structure of a CY influences its representation and comprehension, so that the hybrid view on idiom representation and comprehension can be finely specified. However, the participants’ homogeneity in age and background education in the present study might impose some limitations on the generalization of these findings. Moreover, similar surveys with a control group of two-character words would probably have made the results even more meaningful.

References

Bonin, P., Barry, C., Méot, A., & Chalard, M. (2004). The influence of age of acquisition in word reading and other tasks: A never ending story? Journal of Memory and Language, 50, 456–476. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2004.02.001

Bonin, P., Méot, A., & Bugaiska, A. (2013). Norms and comprehension times for 305 French idiomatic expressions. Behavior Research Methods, 45, 1259–1271. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0331-4

Cacciari, C., & Tabossi, P. (1988). The comprehension of idioms. Journal of Memory and Language, 27, 668–683.

Caillies, S. (2009). Descriptions de 300 expressions idiomatiques: Familiarité, connaissance de leur signification, plausibilité littérale, “décomposabilité” et “prédictibilité.”. L'Année Psychologique, 109, 463–508.

Caillies, S., & Butcher, K. (2007). Comprehension of idiomatic expressions: Evidence for a new hybrid view. Metaphor and Symbol, 22, 79–108.

Caillies, S., & Le Sourn-Bissaoui, S. (2008). Children’s understanding of idioms and theory of mind development. Developmental Science, 11, 703–711.

Chen, G. (Ed.). (2009). Normal dictionary of Chinese Chengyu with full function. Changchun, China: Jilin (in Chinese).

Cronk, B. C., & Schweigert, W. A. (1992). The comprehension of idioms: The effects of familiarity, literalness, and usage. Applied PsychoLinguistics, 13, 131–146.

Cronk, B. C., Susan, D., Lima, S. D., & Schweigert, W. A. (1993). Idioms in sentences: Effects of frequency, literalness, and familiarity. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 22, 59–82.

Cutting, J. C., & Bock, K. (1997). That’s the way the cookie bounces: Syntactic and semantic components of experimentally elicited idiom blends. Memory & Cognition, 25, 57–71.

Gibbs, R. W., & Nayak, N. P. (1989). Psycholinguistic studies on the syntactic behavior of idioms. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 100–138.

Gibbs, R., Nayak, N., & Cutting, C. (1989). How to kick the bucket and not decompose: Analyzability and idiom processing. Journal of Memory and Language, 28, 576–593.

Holsinger, E. (2013). Representing idioms: Syntactic and contextual effects on idiom processing. Language and Speech, 56, 373–394.

Johnston, R. A., & Barry, C. (2006). Age of acquisition and lexical processing. Visual Cognition, 13, 789–845. doi:10.1080/13506280544000066

Konopka, A. E., & Bock, K. (2009). Lexical or syntactic control of sentence formulation? Structural generalizations from idiom production. Cognitive Psychology, 58, 68–101.

Libben, M. R., & Titone, D. A. (2008). The multidetermined nature of idiom processing. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1103–1121. doi:10.3758/MC.36.6.1103

Liu, L., & Cheung, H. T. (2014). Acquisition of Chinese quadra-syllabic idiomatic expressions: Effects of semantic opacity and structural symmetry. First Language, 34, 336–353.

Liu, Y., Li, P., Shu, H., Zhang, Q., & Chen, L. (2010). Structure and meaning in Chinese: An ERP study of idioms. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 23, 615–630.

Robert, P. R., Curt, B., Gary, D. S., & Kathleen, E. M. (2001). Dissociation between syntactic and semantic processing during idiom comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, 1223–1237.

Sprenger, S. A., Levelt, W. J. M., & Kempen, G. (2006). Lexical access during the production of idiomatic phrases. Journal of Memory and Language, 54, 161–184.

State Language Affairs Committee. (2008). Lexicon of common words in contemporary China. Beijing, China: The Commercial Press.

Swinney, D. A., & Cutler, A. (1979). The access and processing of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 523–534.

Tabossi, P., Arduino, L., & Fanari, R. (2011). Descriptive norms for 245 Italian idiomatic expressions. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 110–123. doi:10.3758/s13428-010-0018-z

Titone, D. A., & Connine, C. M. (1994a). Comprehension of idiomatic expressions: Effects of predictability and literality. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 1126–1138. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.20.5.1126

Titone, D. A., & Connine, C. M. (1994b). Descriptive norms for 171 idiomatic expressions: Familiarity, compositionality, predictability, and literality. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 9, 247–270.

Titone, D. A., & Connine, C. M. (1999). On the compositional and noncompositional nature of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Pragmatics, 31, 1655–1674.

Zhang, H., Yang, Y. M., Gu, J. X., & Ji, F. (2013). ERP correlates of compositionality in Chinese idiom comprehension. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 26, 89–112.

Zhou, J. (2004). A study on the structure of Chinese lexicon (in Chinese: Hanyu cihui jiegoulun). Shanghai, China: Shanghai Dictionary Press.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant 14ZDB155.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Zhang, Y. & Wang, X. Descriptive norms for 350 Chinese idioms with seven syntactic structures. Behav Res 48, 1678–1693 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0692-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0692-y