Abstract

Mental time travel (MTT) is the ability to mentally project oneself backward or forward in time in order to remember an event from one’s personal past or to imagine a possible event in one’s personal future. Past and future MTT share many similarities, and there is evidence to suggest that the two temporal directions rely on a shared neural network and similar cognitive structures. At the same time, one major difference between past and future MTT is that future as compared to past events generally are more emotionally positive and idyllic, suggesting that the two types of event representations may also serve different functions for emotion, self, and behavioral regulation. Here, we asked 158 participants to remember one positive and one negative event from their personal past as well as to imagine one positive and one negative event from their potential personal future and to rate the events on phenomenological characteristics. We replicated previous work regarding similarities between past and future MTT. We also found that positive events were more phenomenologically vivid than negative events. However, across most variables, we consistently found an increased effect of emotional valence for future as compared to past MTT, showing that the differences between positive and negative events were larger for future than for past events. Our findings support the idea that future MTT is biased by uncorrected positive illusions, whereas past MTT is constrained by the reality of things that have actually happened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

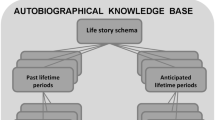

Mental time travel (MTT) is the ability to mentally project oneself backward or forward in time in order to remember an event from one’s personal past or to imagine an event from one’s potential personal future (e.g., Tulving, 2002). In the literature, future MTT is often referred to as episodic future thinking (e.g., Atance & O’Neill, 2001; Szpunar, 2010) or constructive simulation (e.g., Schacter & Addis, 2007; Taylor & Schneider, 1989), whereas past MTT variably is referred to as episodic or autobiographical memory (e.g., Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000; Rubin, 2006; Tulving, 1983). As is the case for memories, episodic future thinking can involve both emotionally positive and negative experiences (e.g., imagining one’s wedding vs. imagining the death of a loved one), as well as mundane or important experiences (e.g., imagining tomorrow’s grocery shopping vs. imagining having your first child). Furthermore, both types of events can be near or far in temporal distance. Both processes involve emotional, sensory, and spatial (p)reliving, as well as the experience of the self being present in the mental projection (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004).

Research on past and future MTT has demonstrated striking similarities between remembering past events and imagining future events in a broad range of research areas (e.g., Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2007; D’Argembeau & Mathy, 2011; Schacter & Addis, 2007). However, researchers have also pointed out one of two major differences (discussed below) between past and future episodic thinking—namely, that imagined future events are more emotionally positive and idyllic than their past counterparts (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Newby-Clark & Ross, 2003; Ross & Newby-Clark, 1998). It has been suggested that this marked positivity bias for future events may reflect important functional differences between the two temporal directions (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010).

In the present article, we will make the case that imagined future events are typically characterized by uncorrected positive illusions (Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999), which may encourage the individual to explore the environment and seek out new goals, whereas remembered past events are generally constrained by the reality imposed by events that already have happened. This implies differences between the two types of MTT with regard to (1) the emotional content of the constructed events, (2) the effects of emotion on the phenomenological characteristics of the constructed events, and (3) the roles the constructed events may play for self, emotion, and behavior regulation. First, we will review studies on the different effects of emotional valence on future as compared to past MTT. We then will describe theories that may explain the increased positivity bias for future MTT from a functional perspective.

An increased positivity bias for the future

The past decade has been marked by an impressive amount of research on MTT, which generally supports the idea that past and future MTT are intimately related and rely on the same basic neurocognitive system (e.g., Addis et al., 2007, Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2008; Atance, 2008; Atance & Meltzoff, 2005; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; Botzung, Denkova, & Manning, 2008; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004, 2006; Gaesser, Sacchetti, Addis, & Schacter, 2011; Hassabis, Kumaran, Vann, & Maguire, 2007; Okuda et al., 2003; Schacter & Addis, 2007; Spreng & Grady, 2010; Szpunar, Chan, & McDermott, 2009; Szpunar & McDermott, 2008; Szpunar, Watson, & McDermott, 2007; Tulving, 1985; Williams et al., 1996; see Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; D’Argembeau & Mathy, 2011, for reviews). At the same time, studies have consistently shown that past and future MTT also differ according to at least two overarching findings. First, behavioral and brain-imaging studies have suggested that the mental construction of a future event is cognitively more demanding than the corresponding construction of a past event. For instance, future MTT is associated with more brain activity than is past MTT (Addis et al., 2007, 2008; Szpunar et al., 2007). This may suggest that future MTT is associated with more schema-based construction, which is consistent with behavioral findings: Past, as compared to future, events are rated higher on measures related to recollection, such as imagery and vividness. On the other hand, future events are rated higher on variables related to self-schemas and abstract knowledge, such as their overall importance, relevance to life story and identity (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; D’Argembeau & Mathy, 2011; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004, 2006; Miles & Berntsen, 2011), and proportion of general versus specific events (e.g., Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; Miles & Berntsen, 2011).

Second, and most importantly here, future as compared to past episodic thinking shows a greater bias in the favor of emotionally positive and idyllic events. Although positive past events are more frequently remembered than negative past events, this positivity bias is even more pronounced for events imagined in the future (e.g., Gallo, Korthauer, McDonough, Tesdale, & Johnson, 2011; Newby-Clark & Ross, 2003; Ross & Newby-Clark, 1998). For example, across different events types (e.g., important, word-cued, and involuntary, as well as freely recalled/imagined events), future events are rated as being more emotionally positive than are past events (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Finnbogadóttir & Berntsen, in press; Newby-Clark & Ross, 2003). Newby-Clark and Ross found that, when participants generated events from their personal past and potential personal futures, they described extremely positive events in both time periods, whereas extremely negative events were found almost exclusively in the past condition. Studies have also shown that future negative events have longer retrieval times than do future positive events (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Newby-Clark & Ross, 2003), suggesting that they are more difficult to imagine, whereas research comparing retrieval times for positive and negative memories have more mixed results (e.g., D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Lishman, 1974; Newby-Clark & Ross, 2003; Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009).

In spite of findings clearly demonstrating an increased positively bias in future as compared to past MTT, researchers have consistently shown a smaller, but nonetheless stable, positivity bias in memory for past events. Across different studies using different sampling techniques, emotionally positive autobiographical memories are reported approximately twice as frequently as their negative counterparts (e.g., Walker, Skowronski, & Thompson, 2003, for a review). Although this bias toward pleasant information may to some degree reflect that people encounter more positive than negative events in their lives, it is also likely to be shaped by biases in autobiographical remembering. First, people’s intensity ratings of both positive and negative memories decrease over time, but this decrease is faster for negative than for positive memories, as is shown by both retrospective and prospective studies (e.g., Walker, Vogl, & Thompson, 1997; see Walker & Skowronski, 2009, for a review). This fading affect bias has also been found for memories of future events (Szpunar, Addis, & Schacter, 2012). Second, studies have shown that negative as compared to positive memories are perceived as being more temporally distant, and it has been proposed that this bias serves a self-regulation function, because temporally close events are more likely to be viewed as belonging to the current self than are temporally more distant events (e.g., Wilson, Gunn, & Ross, 2009, for a review). Third, memories of positive events are more rehearsed across different types of rehearsal (i.e., talking or thinking about an event or having the memory come to mind spontaneously) than are memories of negative events (Berntsen & Thomsen, 2005: Bohn & Berntsen, 2007; Byrne, Hyman, & Scott, 2001; Walker, Skowronski, Gibbons, Vogl, & Ritchie, 2009; but see Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009). Fourth, positive as compared to negative memories are generally rated higher on measures related to imagery, sense of reliving, vividness, and mental time travel (see, e.g., Bohn & Berntsen, 2007; Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009, for reviews), although the effects of emotional intensity, irrespective of valence, are much stronger (Talarico, LaBar, & Rubin, 2004). Fifth, cultural life scripts, referring to schematic representations of culturally expected transitional events in a normal life course (Berntsen & Rubin, 2004), are biased in favor of emotionally positive events that are expected to take place in young adulthood, such as marriage and childbirth (Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Rubin, 2004; Rubin, Berntsen, & Hutson, 2009). Cultural life scripts have been found to structure recall of emotionally positive autobiographical memories, whereas they seem to have less effect on the recall of emotionally negative events (Berntsen & Rubin, 2002, 2004; Berntsen, Rubin, & Siegler, 2011; Rubin & Berntsen, 2003). However, although most biases in autobiographical memory favor positive information, negative memories tend to be more accurate (Bohn & Berntsen, 2007; Kensinger, 2007, 2009; Levine & Pizarro, 2004), and they are remembered with more central (but fewer peripheral) details than are their positive counterparts (Berntsen, 2002; Talarico, Berntsen, & Rubin, 2009).

It has been proposed that these differences between positive and negative memories reflect different functionalities between the two types of memories, such as maintaining a positive self-image versus optimizing personal survival (Taylor, 1991; Taylor & Brown, 1988), or remembering culturally normative life events versus events that violate such expectations and may be associated with emotional distress (Berntsen et al., 2011). According to this view, there is an adaptive value to remembering those aspects of negative events that are necessary for problem solving and the prevention of future mistakes, whereas the boosting of positive memories versus the dampening of negative memories may serve the building of personal and social resources (e.g., Berntsen, 2002; Frederickson & Branigan, 2005; Levine & Bluck, 2004; Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009; Ross & Wilson, 2002; Talarico et al., 2009; Taylor & Brown, 1988). In addition, the overrepresentation of positive events in autobiographical memory is reduced or absent during episodes of dysphoria and depression (e.g., Walker et al., 2003; Williams, 1992). Consistent with this view, Rasmussen and Berntsen (2009) showed that negative as compared to positive memories were more associated with directive (i.e., problem solving and behavior guiding) functions, whereas positive memories were more associated with self-defining and social-bonding functions.

In summary, the positivity bias for autobiographical memory has been explained with reference to different functionalities served by positive and negative memories, such as learning from past mistakes versus optimizing current self-image and social relations. We now turn to possible functional differences between past and future MTT in relation to emotion.

Functional differences between past and future MTT in relation to emotion

Taylor and Brown (1988) reviewed evidence showing that human thought is biased toward an overly positive self-concept, an exaggerated perception of personal control, and an unrealistic optimism for the future. They further proposed that these biases are adaptive, because they encourage the individual to form social relationships and seek out new opportunities in spite of seemingly likely risks of disappointment and failure. These biases hold for both past and future MTT, but are likely to be reduced in past relative to future MTT, due to uncorrected positive illusions for the latter.

Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative affect have been described extensively in research on emotion (e.g., Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999; Taylor, 1991; Taylor & Brown, 1988; Vaish, Grossmann, & Woodward, 2008). Taylor (1991) reviewed a large number of studies showing that negative events evoke stronger physiological, cognitive, behavioral, and social reactions than do neutral or positive events, which then are followed by rapid responses that dampen, minimize, or even erase the impact of the event. In a similar vein, Cacioppo and Gardner proposed that the organism in a neutral environment is motivated to approach novel objects and to expect positive outcomes of future events rather than avoiding them. In this view, positive emotion serves as a cue to stay on course and explore the environment, whereas negative emotion is a cue for mental and behavioral adjustment (p. 206). It appears that negative emotion may serve such behavioral adjustment in the case of past MTT, whereas it may be absent or highly reduced in future MTT. Consistent with this idea, recent findings have suggested that positive future events are remembered with more detail than are negative future events, whereas positive and negative past events are remembered with equal detail (Gallo et al., 2011). This does not mean that imagining a negative event in your personal future is always maladaptive. However, the adaptability of imagining such events may be limited to situations in which they are concretely relevant, such as when anticipating immediate obstacles to one’s goals (Taylor, Pham, Rivkin, & Armor, 1998). For instance, imagining failing an upcoming exam may be a strong motivational factor when deciding whether or not to study, whereas imagining the same event outside the relevant context may create unnecessary fear and prevent action.

If these assumptions are valid, it would suggest that future as compared to past MTT serves important functions for emotion and self-regulation by selectively restraining the phenomenological vividness of potential future negative events, whereas past MTT provides us with valuable corrections of thought and behavior and may be more associated with problem solving.

The study

The goal of the present study was to examine the effects of emotional valence on the perceived function, phenomenological characteristics, and contents of events imagined to happen in the future versus remembered past events. We therefore asked participants to generate emotionally positive and negative events from their personal past and potential future, and then to answer for each event a series of questions related to the perceived functionalities and phenomenological characteristics of the constructed events. In order to probe functionalities, we included questions addressing three theoretically and empirically derived functions of autobiographical memory (i.e., the directing-behavior, self-defining, and social-bonding functions; e.g., Bluck, Alea, Habermas, & Rubin, 2005; Cohen, 1998; Pillemer, 1992). These questions were developed and validated in previous work on the function of autobiographical memory in relation to emotion (Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009). We examined the phenomenological characteristics of the constructed events by including theoretically derived phenomenological measurements of autobiographical memory (e.g., Brewer, 1996; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000; Rubin, 2006; Tulving, 2002), which also have been successfully applied in studies on imagined future events (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008).

We expected to replicate previous main effects from the autobiographical memory literature, showing that positive as compared to negative events are rated as being higher on self and social function, temporal closeness, rehearsal, sensory imagery, sense of (p)reliving, vividness, and mental time travel. Furthermore, we expected to replicate previous main effects from research on MTT, showing that past events are rated higher on variables related to imagery, sensory detail, and reliving, whereas future events are rated higher on variables related to self-relevance and scripted knowledge, such as the proportion of general versus specific events. However, on the basis of the asymmetrical effects of valence on past and future events, we expected most of these main effects to be qualified by interactions, indicating a stronger effect of emotional valence for future than for past events, with the differences between ratings of positive and negative events being larger for future than for past events.

Method

Participants

A group of 158 (132 female, 26 male; mean age 24.44 years, SD = 4.13, range 21–44 years) psychology undergraduates participated as part of a psychology research methods course. All of the participants were informed that their responses were anonymous, and it was clearly stated that they were free to withdraw at any point during the procedure.

Design

We used a 2 (positive vs. negative) × 2 (future vs. past) within-subjects design. Each participant generated one of each type of event. The order of the events was randomized across two groups, with 80 and 78 participants in each group.

Procedure

The participants were tested in a group session. They were asked to recall the four events in either the following or the reversed order: past negative, past positive, future negative, and future positive. After writing a brief description of the event, they moved on to answering a questionnaire concerning event characteristics and the centrality of the event for the person’s identity and life story. The participants were instructed to recall an event from their personal past or to imagine an event in their potential personal future. Because we were interested in the specificity of events evoked across the four conditions, the participants were not asked to generate either specific or general events. They were instructed to choose the first event that came to mind in response to the cue and to keep the event in mind while answering the questions. The instructions for the past and future events were the same, except for the reference to remembered past versus imagined future events.

Questionnaire

The questions asked when eliciting all memories and future event representations are presented in Table 1 and the Appendix, translated from Danish. The questions were derived or modified from Rubin and Siegler (2004), Rasmussen and Berntsen (2009), and Berntsen and Bohn (2010). The table depicts the questions as they were formulated for the past condition. The questions for the future condition were the same, except that the wordings were changed in order to refer to future events. For instance, Question 5, addressing social function, was changed from “I have often shared this memory with other people” to “I will often share this imagined future event with other people,” and Question 15, addressing consequences, was changed from “The event had consequences” to “The imagined future event will have consequences.” The Appendix shows all questions as they were asked for the future events. As is shown in Table 1, most of the questions were rated on 7-point scales, except for Questions 1 and 2, addressing the distance in time of the remembered or imagined event from the present moment, and Question 9, addressing the specificity of the event. Questions 3–6 addressed the perceived function of the memories. Questions 7, 8, 10–15, and 19–20 addressed the amount and type of subjective re-experiencing associated with the events. Questions 16–18 addressed different kinds of rehearsal. All of the questions were explained thoroughly by the experimenter before the session started, and the experimenter was also in the room during the entire session in order to clarify any questions.

On the last page of the questionnaire, participants filled in the seven-item version of the centrality-of-event scale (CES; Berntsen & Rubin, 2006). This scale addressed the centrality of the remembered event to personal identity, the extent to which the memory was used as a reference point for the attribution of meaning to other events in memory, and whether the event was considered a turning point in the person’s life story. It contains seven questions that are rated on 5-point Likert scales (e.g., Item 1: “I feel that this event has become part of my personal identity,” 1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). For the future condition, the individual items in the CES were changed in order to refer to imagined future events (e.g., Item 1: “I feel that this event will become part of my personal identity”). The reliability for the seven items included in the CES was acceptable for all four events (i.e., Chronbach’s alphas ranging from .91 to .94).

Content analysis

We first coded the content of the events according to the 36 (including “other”) cultural life script categories identified by Berntsen and Rubin (2004, Table 3) in a Danish sample (see also Rubin et al., 2009). For an overview of the different life script categories, see Table 3 below. All non-cultural-life-script events (i.e., events that were coded as “other”) were then coded according to 17 content categories derived from Schlagman, Schulz, and Kvavilashvili (2006). The categories were Person (i.e., the event is primarily about another person); Accidents including injuries and illnesses (i.e., physical stress); Stressful events excluding accidents, illnesses, deaths, and funerals (i.e., psychological stress); Holidays; Conversations; Leisure/sports activities; Objects/places (i.e., the event is primarily about an object or a place); Going out (e.g., going to a pub/dancing); Work/university; Romantic involvement; School (e.g., elementary and high school); Deaths/funerals; Special occasions (e.g., birthdays, weddings); Births; Traveling/journeys; War/army; and Miscellaneous. The coding was carried out in accordance with the guidelines described by Schlagman et al. We first attempted to classify each event description so that the category captured all of the themes mentioned in the description. For instance, some descriptions contained a number of themes, which could all be classified into the superordinate category of School. If an event description contained more than one theme and the themes could not be classified under one overarching category, we based the categorization on the theme that was mentioned first. The event descriptions were coded by the first author and an independent coder. Disagreements were solved by an independent judge. The interrater agreement for the cultural-life-script coding was 90.3 %. The corresponding value for non-cultural-life-script events was 93.4 %.

Results

We first compare the four events on function, phenomenological characteristics, and centrality of the event to the person’s identity and life story, as measured on the CES. Next, we examine the frequencies of the remembered past versus imagined future events as a function of their distance from the present. Finally, we examine the content of the four events according to the cultural-life-script versus non-life-script categories. Twelve participants did not record a future negative event, whereas all participants made a record of the remaining three events.

Comparisons of emotionally negative versus positive events in the past versus future

We conducted a series of 2 (time: past vs. future) × 2 (valence: negative vs. positive) repeated measures ANOVAs to compare the ratings for the four events. The results, as well as the means and standard deviations, are presented in Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2. As is shown by Table 2, we found a large number of main effects of temporal direction, consistent with our hypotheses. As expected, past events were rated higher on sensory imagery, (p)reliving, mentally traveling back or forward in time, and vividness, whereas future events were rated higher on self-function, consequences, life script proportion, proportion of general events, and centrality of the event to the person’s identity and life story. In addition, past events were rated higher than future events on social function and conversational rehearsal. These findings are largely consistent with the idea that future events require more constructive effort than past events, and that the construction of future as compared to past events therefore relies more on scripted knowledge and self-schemas (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Schacter & Addis, 2007; Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007), whereas the construction of past events relies more on factors related to encoding and maintenance (Berntsen & Bohn, 2010). As is also shown by Table 2, several main effects of valence were found, of which most were consistent with previous findings for past events. As expected, we found a main effect of valence for the self and social functions, as well as for the intimacy function, indicating that positive events were rated higher than negative events on these functions. As was also expected, positive events were rated higher than negative events on most phenomenological characteristics, with the exception of physical reaction, action/reaction, consequences, involuntary rehearsal, and emotional intensity. No main effect of valence was found for the directive function, but the difference was in the expected direction for past events (see Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009).

Importantly, the main effects of valence and temporal direction were qualified by a number of significant interactions. Most of these are illustrated in Fig. 1. The interaction for temporal distance is shown in Fig. 2, to which we will turn shortly. As is shown by Fig. 1, these interactions reflected that ratings of sensory imagery, (p)reliving, rehearsal, functions, belief, vividness, and mentally traveling in time were higher for positive events, but more so in the future direction. As is also shown by Fig. 1, for the following variables—the directive function, involuntary rehearsal, belief, vividness, and sensory imagery—the difference between positive and negative events was significant for the future (.0005 < ps < .001), but not for the past condition (.10 < ps < .76). For the remaining variables, the effects of emotional valence were still notably more pronounced for future (.0005 < ps < .004) than for past (.0005 < ps < .04) events, although the differences between positive and negative memories also reached significance for these variables. There was one exception to this pattern: The interaction for emotional valence was in the opposite direction, with negative future events being rated as more emotionally negative than negative past events, whereas there was no significant difference on valence ratings between positive future and past events.

Consistent with previous work (e.g., Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008; Miles & Berntsen, 2011), we found that future as compared to past events included fewer specific events. In order to examine whether this difference might be driving some of the interactions, we conducted another series of 2 (time: past vs. future) × 2 (valence: negative vs. positive) repeated measures ANOVAs including only the participants who reported a specific event in all four conditions, leaving a sample of 40 participants. In spite of this marked reduction of the sample size, nine out of the 13 interactions remained significant (i.e., directive and social functions; belief; vividness; sensory imagery; conversational, voluntary, and involuntary rehearsal; and temporal distance). For the remaining four variables (i.e., self-function, mental time travel, emotional valence, and CES score), numerical differences in the expected direction were observed. Furthermore, with the exception of the interaction for belief, which was in the opposite direction, the directions of all other interactions were similar to those from the original analyses (see Table 2 and Fig. 1), implying that the observed differences in specificity proportions for past versus future events were not driving the interactions.

Frequencies of the four event types as a function of their temporal distance from the present

As is shown by Table 2, negative events were rated as being more distant in time from the current moment than were positive events, consistent with the temporal self-appraisal theory for past events (see, e.g., Ross & Wilson, 2002; Wilson & Ross, 2003). However, as is shown by Fig. 2 (top panel), future negative events were rated as being markedly more distant in time than were past negative events, again consistent with an increased positivity bias for the future, in that placing the negative events in the distant (rather than the closer) future may reduce their ability to affect the self and to arouse emotions. Figure 2 (bottom panel) shows the distribution of positive and negative events across time in 2-year time bins. As is shown by the figure, negative as compared to positive events were characterized by a dominance of temporally distant events for both the past and future condition, but again this increased effect of emotional valence was much more pronounced for the future condition. Only 55.5 % of the future negative events were expected to take place within the next 10 years, whereas the corresponding values for future positive, past negative, and past positive events were 93.7 %, 87.3 %, and 76.4 %, respectively. This difference in temporal distribution was significant [χ2(1) = 3.98, p < .05]. In contrast to previous work on word-cued, important, and involuntary past and future event representations (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Jacobsen, 2008), future events were rated as being more temporally distant from the present than were past events. This was most likely due to the use of emotion cues in the present study.

Content analysis according to life-script versus non-life-script categories

Consistent with the idea that the construction of future events relies more on scripts and self-schemas (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Schacter & Addis, 2007; Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007), future as compared to past events showed a greater overlap with life-script categories, regardless of valence, and consistent with previous work showing a strong positivity bias for life-script events (e.g., Berntsen et al., 2011), positive events overlapped more with the life-script categories than did their negative counterparts in both the past and future condition. As is shown by Table 2, 74 % of the future positive events versus 52 % of the future negative events were about life script events, whereas the corresponding values for past positive and past negative events were 42 % and 31 %, respectively. Table 3 shows the distribution of the four event types according to the 35 life-script categories identified by Berntsen and Rubin (2004). Replicating Berntsen and Bohn (2010), the table largely illustrates where our population of young students were in life. The most frequently mentioned life-script categories for past positive events were college, fall in love, and long trip, whereas the most frequently mentioned categories for future positive events were having children and marriage. These categories are identical to the most dominant categories found by Berntsen and Bohn for important and word-cued events. For the negative events, the most frequently reported categories were other’s death and parent’s death for both past and future events, with other’s death being the more dominant category for the past, whereas parent’s death was more dominant for the future. However, 41 % of the future negative events concerned deaths of significant others, whereas this was the case for only 24 % of the past negative events. A closer examination of the frequencies showed that this difference was due to a larger percentage of events concerning a parent’s death in the future relative to the past condition (i.e., 24 % vs. 6%, respectively), whereas other types of death-related events were almost equally distributed across the two temporal directions (i.e., 20 % vs. 18 % for negative past relative to negative future events). Because a number of events were classified as “other” in the life-script categories, we classified these non-life-script events according to the coding system developed by Schlagman et al. (2006). The results are depicted in Table 4. For both past and future positive events, the most frequently mentioned non-life-script category was person, whereas for negative events, the most dominant non-life-script category was stressful events. For future negative events, work/university was also a frequently mentioned category.

In order to examine whether the larger proportion of negative events related to a parent’s death in the future condition could account for some of the interactions, we conducted another series of 2 (time: past vs. future) × 2 (valence: negative vs. positive) repeated measures ANOVAs, but this time we removed all events related to a parent’s death from the analyses, leaving a sample of 115 participants. Nine out of the 13 significant interactions from the original analyses remained significant (i.e., directive function; mental time travel; belief; vividness; sensory imagery; conversational, voluntary, and involuntary rehearsal; and emotional valence), two came out as statistical trends (i.e., .06 < ps < .08; self-function and CES score), and two came out as nonsignificant (i.e., social function and temporal distance). Importantly, with the exception of social function, which showed a nonsignificant trend in the opposite direction, the direction of all of these interactions were consistent with the original analyses (see Table 2 and Fig. 1), suggesting that the observed differences in the frequencies of events related to the death of a parent were not driving the interactions.

Discussion

Earlier work had mostly used word cues to generate past and future MTT. Here, we asked our participants to generate past and possible future events in response to requests for emotionally positive versus negative events. Similar to the previous findings (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004), past events were rated higher on sensory imagery, sense of (p)reliving, mentally traveling back or forward in time, and vividness, whereas future events were rated higher on self-function, consequences, life-script correspondence, proportion of general events, and centrality of the event to the person’s identity and life story. Positive events were rated higher on sensory imagery, sense of (p)reliving, vividness, rehearsal, MTT, temporal closeness, and self and social function, regardless of temporal direction. Similar findings had been obtained previously for autobiographical remembering (e.g., Bohn & Berntsen, 2007; Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009). However, across most variables, we found an increased effect of emotional valence for future as compared to past events, showing a marked positivity bias for the future relative to the past. Furthermore, this pronounced effect of emotional valence also held when we reduced the sample to those participants who reported specific events in all four conditions, and when we reduced the sample to events that were not related to the death of a parent. There was one exception from this general pattern: Consistent with previous work (e.g., Caruso, Gilbert, & Wilson, 2008; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Van Boven & Ashworth, 2007), the interaction for emotional valence was in the opposite direction, with negative future events being rated as more emotionally negative than negative past events, whereas there was no difference on valence ratings between positive future and past events.

These findings suggest that the two temporal directions may serve different functions for self, emotional and behavior regulation by selectively reducing the phenomenological vividness of future negative events. First, previous work has shown that positive as compared to negative memories are more associated with self-regulating and social-bonding functions, whereas negative memories are more associated with directive (i.e., problem-solving and behavior-adjusting) functions (Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2009). We replicated the results for the self and social functions, but found that these effects were even more pronounced for the future than for the past condition. This is consistent with our assumption that future MTT plays a more central role for self-regulation and for the maintenance of a positive self-image than does past MTT. Second, although negative memories were rated only slightly higher than positive memories on the directive function, there was a larger effect in the opposite direction for future events, consistent with the view that past as compared to future MTT, due to its higher association with negative affect, provides valuable corrections of thought and behavior, and therefore may be more associated with problem solving, planning, and learning (Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999; Taylor & Brown, 1988). Simulating a future event may of course also serve some of these functions (e.g., D’Argembeau, Renaud, & Van der Linden, 2011; D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004), but from the present findings, it seems more likely that people adjust their thoughts and behavior by imagining future success, as opposed to imagining future mistakes and failures, when faced with an open-ended task. Imagining a negative event in one’s personal future may be more context- and cue-dependent, such as being faced with the reality of an upcoming exam or divorce. Third, positive future events were rated higher on measures on sensory imagery, (p)reliving, and rehearsal, as compared to negative future events, whereas these differences were either reduced or absent for past MTT. Fourth, in agreement with temporal self-appraisal theory (Ross & Wilson, 2002; Wilson & Ross, 2003) and the idea of an enhanced positivity bias for the future, positive future events were dated as temporally less distant in time than were negative future events, whereas a similar, but less pronounced, difference was seen for past MTT. Overall, these findings are consistent with the proposal that self and emotion regulation may be more closely associated with future MTT, whereas behavior regulation may be more strongly associated with past MTT.

In an earlier study, D’Argembeau and Van der Linden (2004) asked participants to generate past and future events that were emotionally positive and negative and to rate the phenomenological characteristics of the events. In contrast to the present study, they also manipulated temporal distance by asking for temporally near (within 1 year) and far (between 5 and 10 years ago) events. D’Argembeau and Van der Linden reported some interactions between emotional valence and temporal direction, consistent with the present findings. However, they found that the effects of valence were mostly parallel in the two conditions, for which reason they concluded that past and future MTT serve similar functions for self-enhancement. In contrast, our findings indicate that when temporal distance is not manipulated together with both temporal direction and emotional valence, participants prefer to imagine negative events in their potential future as much farther away from the current moment than is the case for imagined positive events or remembered negative or positive events, allowing for the full effect of the increased positivity bias for future relative to past MTT. This is consistent with the view that the temporal self-enhancement bias (Ross & Wilson, 2002; Wilson & Ross, 2003) is stronger for future than for past MTT.

The increased positivity bias for future as compared to past MTT was also reflected in the content of the events. Consistent with cultural-life-script theory (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; Berntsen & Rubin, 2004), positive as compared to negative events showed a greater overlap with the life-script categories in both the past and future conditions, but a larger percentage of the future negative events involved the death of a parent, as compared to their past counterparts. One might suggest that the larger percentage of events related to a parent’s death in the future condition might have driven some of the interactions, but we found largely similar effects of emotional valence when we removed all such events from the sample, showing that this was not the case. Although the interaction for temporal distance disappeared in these analyses, most of the remaining interactions still came out as significant. Furthermore, although future negative events showed greater overlap with the life-script categories than did their past counterparts, negative as compared to positive life-script events were less temporally locked, according to cultural conventions. Typically, positive life-script events such as falling in love, getting an education, getting married, or having children are expected to take place at culturally fixed time slots, whereas negative life-script events, such as the death of a loved one or one’s own death or divorce, are temporally less fixed and can happen at various times across the life span (see Berntsen & Rubin, 2004). Together, these results suggest that people rely heavily on the cultural life script when they attempt to construct future events. Since the life script is positively biased and contains very few negative events, of which most are death-related (see Berntsen & Rubin, 2004, and Table 3), there may simply be a more limited range of schematized negative events from which to construct future events, whereas the corresponding construction of past negative events is to a greater extent assisted by memories of events that have actually happened. This may also help to explain the (in the present context) paradoxical finding that the future negative events were rated as being more emotionally negative than past negative events. The enhanced ratings of negative emotion in the future condition may reflect a greater influence of culturally shared schemata in the construction of the imagined future events than is the case for past negative events.

Concluding comments

In the present study, we have demonstrated an increased positivity bias for imagined future relative to remembered past events. We found that the perceived clarity and self-relevance of future positive (vs. future negative) events were enhanced relative to what was the case for positive (vs. negative) past events. Our findings suggest that, as compared to past MTT, future MTT is characterized to a greater extent by uncorrected positive illusions, thereby motivating us to explore the environment and to set and approach new goals with the expectation that we will succeed. In contrast, past MTT is constrained by the reality of events that have already happened, allowing for important corrections of thoughts and behavior and the ensuing prevention of future mistakes. Unlike the future, the past can only be reinterpreted. As the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote: “It is true, as philosophers say, that life has to be understood backwards. But in addition, they forget the other sentence: that it has to be lived forwards” (Kierkegaard, 1868–1978, quoted in Berntsen, 1999, p. 124). The differential effects of emotion on past versus future MTT help us to do both.

References

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1363–1377. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). Age-related changes in the episodic simulation of future events. Psychological Science, 19, 33–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02043.x

Atance, C. M. (2008). Future thinking in young children. Current Directions on Psychological Science, 17, 295–298. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00593.x

Atance, C. M., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2005). My future self: Young children’s ability to anticipate and explain future states. Cognitive Development, 20, 341–361.

Atance, C. M., & O’Neill, D. K. (2001). Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5, 533–539. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323–370. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Berntsen, D. (1999). Moments of recollection: A study of involuntary autobiographical memories. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Psychology, Aarhus University.

Berntsen, D. (2002). Tunnel memories for autobiographical events: Central details are remembered more frequently from shocking than from happy experiences. Memory & Cognition, 30, 1010–1020.

Berntsen, D., & Bohn, A. (2010). Remembering and forecasting: The relation between autobiographical memory and episodic future thinking. Memory & Cognition, 38, 265–278. doi:10.3758/MC.38.3.265

Berntsen, D., & Jacobsen, A. S. (2008). Involuntary (spontaneous) mental time travel into the past and future. Consciousness & Cognition, 17, 1093–1104. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.001

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2002). Emotionally charged autobiographical memories across the life span. The recall of happy, sad, traumatic and involuntary memories. Psychology and Aging, 17, 636–652. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.636

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2004). Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 32, 427–442. doi:10.3758/BF03195836

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behavior Research & Therapy, 44, 219–234.

Berntsen, D., Rubin, D. C., & Siegler, I. C. (2011). Two versions of life: Emotionally negative and positive life events have different roles in the organization of life story and identity. Emotion, 11, 1190–1201. doi:10.1037/a0024940

Berntsen, D., & Thomsen, D. K. (2005). Personal memories for remote historical events: Accuracy and phenomenology of flashbulb memories related to World War II. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 134, 242–257. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.134.2.242

Bluck, S., Alea, N., Habermas, T., & Rubin, D. C. (2005). A TALE of three functions: The self-reported uses of autobiographical memory. Social Cognition, 23, 97–117. doi:10.1521/soco.23.1.91.59198

Bohn, A., & Berntsen, D. (2007). Pleasantness bias in flashbulb memories: Positive and negative flashbulb memories of the fall of the Berlin Wall among East and West Germans. Memory & Cognition, 35, 565–577. doi:10.3758/BF03193295

Botzung, A., Denkova, E., & Manning, L. (2008). Experiencing past and future personal events: Functional neuroimaging evidence on the neural bases of mental time travel. Brain and Cognition, 66, 202–212. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.07.011

Brewer, W. F. (1996). What is recollective memory? In D. C. Rubin (Ed.), Remembering our past: Studies in autobiographical memory (pp. 19–66). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Byrne, C. A., Hyman, I. E., & Scott, K. L. (2001). Comparisons of memories for traumatic events and other experiences. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, 119–133. doi:10.1002/acp.837

Cacioppo, J. T., & Gardner, W. L. (1999). Emotions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 191–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.191

Caruso, E. M., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2008). A wrinkle in time: Asymmetric valuation of past and future events. Psychological Science, 19, 796–801.

Cohen, G. (1998). The effects of ageing in autobiographical memory. In C. P. Thompson, D. J. Herrman, D. Bruce, J. D. Read, D. G. Payne, & M. P. Toglia (Eds.), Autobiographical memory: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 105–123). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107, 261–288. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.261

D’Argembeau, A., & Mathy, A. (2011). Tracking the construction of episodic future thoughts. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140, 258–271.

D’Argembeau, A., Renaud, O., & Van der Linden, M. (2011). Frequency, characteristics and functions of future-oriented thought in daily life. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 96–103. doi:10.1002/acp.1647

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2004). Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: Influences of valence and temporal distances. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 844–858. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.007

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2006). Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: The effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Consciousness and Cognition, 15, 342–350.

Finnbogadóttir, H., & Berntsen, D. (in press). Involuntary future projections are as frequent as involuntary memories, but more positive. Consciousness and Cognition.

Frederickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19, 313–332. doi:10.1080/02699930441000238

Gaesser, B., Sachetti, D. C., Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2011). Characterizing age-related changes in remembering the past and imagining the future. Psychology and Aging, 26, 80–84.

Gallo, D. A., Korthauer, L. E., McDonough, I. M., Tesdale, S., & Johnson, E. J. (2011). Age-related positivity effects and autobiographical memory detail: Evidence from a past/future source memory task. Memory, 19, 641–652.

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D., & Maguire, E. A. (2007). Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 1726–1731. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610561104

Kensinger, E. A. (2007). Negative emotion enhances memory accuracy: Behavioral and neuroimaging evidence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 213–218. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00506.x

Kensinger, E. A. (2009). Remembering the details: Effects of emotion. Emotion Review, 1, 99–113. doi:10.1177/1754073908100432

Levine, L. J., & Bluck, S. (2004). Painting with broad strokes: Happiness and the malleability of event memory. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 559–574. doi:10.1080/02699930341000446

Levine, L. J., & Pizarro, D. A. (2004). Emotion and memory research: A grumpy overview. Social Cognition, 22, 530–554. doi:10.1521/soco.22.5.530.50767

Lishman, W. A. (1974). The speed of recall of pleasant and unpleasant experiences. Psychological Medicine, 4, 212–218.

Miles, M. N., & Berntsen, D. (2011). Odour-induced mental time travel into the past and future: Do odour cues retain a unique link to our distant past? Memory, 19, 930–940.

Newby-Clark, I. R., & Ross, M. (2003). Conceiving the past and future. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 807–818. doi:10.1177/0146167203029007001

Okuda, J., Fujii, T., Ohtake, H., Tsukiura, T., Tanji, K., Suzuki, K., & Yamadori, A. (2003). Thinking of the future and the past: The roles of the frontal pole and the medial temporal lobes. NeuroImage, 19, 1369–1380. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00179-4

Pillemer, D. B. (1992). Remembering personal circumstances: A functional analysis. In E. Winograd & U. Neisser (Eds.), Affect and accuracy in recall: Studies of “flashbulb” memories. Emory Symposium in Cognition 4 (pp. 236–264). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2009). Emotional valence and the functions of autobiographical memories: Positive and negative memories serve different functions. Memory & Cognition, 37, 477–492. doi:10.3758/MC.37.4.477

Ross, M., & Newby-Clark, I. A. (1998). Construing the past and future. Social Cognition, 16, 133–150.

Ross, M., & Wilson, A. E. (2002). It feels like yesterday: Self-esteem, valence of personal past experiences, and judgments of subjective distance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 792–803. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.792

Rubin, D. C. (2006). The basic systems model of episodic memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 277–311.

Rubin, D. C., & Berntsen, D. (2003). Life scripts help to maintain autobiographical memories of highly positive, but not highly negative, events. Memory & Cognition, 31, 1–14. doi:10.3758/BF03196077

Rubin, D. C., Berntsen, D., & Hutson, M. (2009). The normative and the personal life: Individual differences in life scripts and life story events among USA and Danish undergraduates. Memory, 17, 54–68. doi:10.1080/09658210802541442

Rubin, D. C., & Siegler, I. C. (2004). Facets of personality and the phenomenology of autobiographical memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 913–930. doi:10.1002/acp.1038

Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 773–786. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2087

Schlagman, S., Schulz, J., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2006). A content analysis of involuntary autobiographical memories: Examining the positivity effect in old age. Memory, 14, 161–175. doi:10.1080/09658210544000024

Spreng, R. N., & Grady, C. L. (2010). Patterns of brain activity supporting autobiographical memory, prospection, and theory of mind, and their relationship to the default mode network. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22, 1112–1123. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21282

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30, 299–313.

Szpunar, K. K. (2010). Episodic future thought: An emerging concept. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 142–162.

Szpunar, K. K., Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2012). Memory for emotional simulations: Remembering a rosy future. Psychological Science, 23, 24–29.

Szpunar, K. K., Chan, J. C. K., & McDermott, K. B. (2009). Contextual processing in episodic future thought. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 1539–1548.

Szpunar, K. K., & McDermott, K. B. (2008). Episodic future thought and its relation to remembering. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 330–334. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.04.006

Szpunar, K. K., Watson, J. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2007). Neural substrates of envisioning the future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 642–647.

Talarico, J. M., Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2009). Positive emotions enhance recall of peripheral details. Cognition & Emotion, 23, 380–398. doi:10.1080/02699930801993999

Talarico, J. M., LaBar, K. S., & Rubin, D. C. (2004). Emotional intensity predicts autobiographical memory experience. Memory & Cognition, 32, 1118–1132. doi:10.3758/BF03196886

Taylor, S. E. (1991). Asymmetrical effect of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 67–85. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.67

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193

Taylor, S. E., Pham, L. B., Rivkin, I. D., & Armor, D. A. (1998). Harnessing the imagination: Mental simulation, self-regulation, and coping. American Psychologist, 53, 429–439.

Taylor, S. E., & Schneider, S. K. (1989). Coping and the simulation of events. Social Cognition, 7, 174–194.

Tulving, E. (1983). Elements of episodic memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26, 1–12. doi:10.1037/h0080017

Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 1–25. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114

Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social–emotional development. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 383–403. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383

Van Boven, L., & Ashworth, L. (2007). Looking forward, looking back: Anticipation is more evocative than retrospection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 289–300.

Walker, W. R., & Skowronski, J. J. (2009). The fading affect bias: But what the hell is it for? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 1122–1136. doi:10/1002/acp.1614

Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., Gibbons, J. A., Vogl, R. J., & Ritchie, T. D. (2009). Why people rehearse their memories: Frequency of use and relations to the intensity of emotions associated with autobiographical memories. Memory, 17, 760–773. doi:10.1080/09658210903107846

Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., & Thompson, C. P. (2003). Life is pleasant—and memory helps to keep it that way! Review of General Psychology, 7, 203–210. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.7.2.203

Walker, W. R., Vogl, R. J., & Thompson, C. P. (1997). Autobiographical memory: Unpleasantness fades faster than pleasantness over time. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 11, 399–413. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199710)11:5<399::AID-ACP462>3.0.CO;2-E

Williams, J. M. G. (1992). Autobiographical memory and emotional disorders. In S.-Å. Christianson (Ed.), The handbook of emotion and memory: Research and theory (pp. 451–477). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Williams, J. M. G., Ellis, N. C., Tyers, C., Healy, H., Rose, G., & MacLeod, A. K. (1996). The specificity of autobiographical memory and imageability of the future. Memory & Cognition, 24, 116–125. doi:10.3758/BF03197278

Wilson, A. E., Gunn, G. R., & Ross, M. (2009). The role of subjective time in identity regulation. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 1164–1178. doi:10/1002/acp.1617

Wilson, A. E., & Ross, M. (2003). The identity function of autobiographical memory: Time is on our side. Memory, 11, 137–149. doi:10.1080/741938210

Author note

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation, the Danish Council for Independent Research: Humanities (FKK) and the MindLab UNIK initiative at Aarhus University, which is funded by the Danish Ministry of Science and Technology and Innovation. We thank Meike Bohn and Annette Bohn for their assistance in the coding procedure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Questions asked for the events in the study shown for the future condition (translated from Danish)

-

1.

Age at event: How old are you when the imagined future event takes place?

-

2.

Days ahead: If you indicated your current age in Question number 1, how many days from today is the event in the future?

-

3.

Directive: I think of this imagined future event in order to handle present or future situations.

-

4.

Self: This imagined future event tells me something about my identity.

-

5.

Social: I will often share this imagined future event with other people.

-

6.

Intimacy: Imagining this future event gives me a sense of belonging with other people.

-

7.

Physical: The imagined future event triggered a physical reaction—for instance, palpitations, feeling restless, tension, fear, laughter.

-

8.

Action: The imagined future event triggered an action—for instance, deciding to do the dishes, buying a special present for another person, listening to a certain song from my collection.

-

9.

Specificity: The imagined future event deals with (a concrete event that will happen on a specific day vs. a mixture of similar events that will happen on more than one day).

-

10.

Mood change: This imagined future event affected my mood.

-

11.

Back/forward in time: The imagined future event made me feel as if I was traveling forward in time to the actual situation.

-

12.

P/Reliving: While imagining the future event, if feels as though I prelive it in my mind.

-

13.

Belief: I am convinced that the future event will take place exactly as I imagine it.

-

14.

Sensory imagery: While imagining this future event, I can see and hear it in my mind.

-

15.

Consequences: The imagined future event will have consequences.

-

16.

Conversational rehearsal: I have previously talked about the imagined future event.

-

17.

Voluntary rehearsal: I have previously thought deliberately about the imagined future event.

-

18.

Involuntary rehearsal: The imagined future event has previously popped up in my mind by itself—that is, without me trying to imagine it.

-

19.

Valence: The feelings I experience as I imagine the future event are (extremely negative vs. extremely positive).

-

20.

Intensity: The feelings I experience as I imagine the future event are intense.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rasmussen, A.S., Berntsen, D. The reality of the past versus the ideality of the future: emotional valence and functional differences between past and future mental time travel. Mem Cogn 41, 187–200 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0260-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0260-y