Abstract

This study explored how interpersonal relationships modulate moral evaluations in moral dilemmas. Participants rated moral acceptability in response to altruistic (prescriptive) and selfish (proscriptive) behavior conducted by allocators (i.e., a friend or stranger), toward the participants themselves or another stranger in a modified Dictator Game (Experiments 1 and 2). Event-related potential (ERP) data were recorded as participants observed the allocators’ behavior (Experiment 2). Moral acceptability ratings showed that when the allocator was a friend, participants evaluated the friend’s altruistic and selfish behavior toward another stranger as being less morally acceptable than when their friend showed the respective behavior toward the participants themselves. The ERP results showed that participants exhibited more negative medial frontal negativity (MFN) amplitude whether observing a friend’s altruistic or selfish behavior toward a stranger (vs. participant oneself), indicating that friends’ altruistic and selfish behaviors toward strangers (vs. participants) were processed as being less acceptable at the earlier and semi-automatic processing stage in brains. However, this effect did not emerge when the allocator was a stranger in subjective ratings and MFN results. In the later-occurring P3 component, no interpersonal relationship modulation occurred in moral evaluations. These findings suggest that interpersonal relationships affect moral evaluations from the second-party perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Moral evaluation, a core content in moral cognition research, is defined as judging the moral acceptability or appropriateness of another’s behavior in a moral dilemma (Garrigan et al., 2016; Van Bavel et al., 2015). Generally, people evaluate the moral acceptability of one’s behavior according to the types of behavior (Anderson et al., 2020). Previous studies have classified such behavior into two types, i.e., prescriptive and proscriptive behavior (Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009; Noval & Stahl, 2017; Zhan et al., 2020). According to this classification, prescriptive morality indicates that people have established a positive desire and activated the motivation to do something good, whereas proscriptive morality indicates that people should overcome a negative desire and restrain a motivation to do something bad (Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009; Noval & Stahl, 2017). Therefore, if a person engages in prescriptive behavior, such as altruistic giving or helping, she/he would be evaluated as morally acceptable, because this target person’s altruistic behavior promotes the interests of others at a cost to oneself (Cushman, 2015; Hu et al., 2017a, b; Yuan et al., 2021). Conversely, proscriptive behavior, such as selfish behavior, is motivated by a desire to benefit oneself, which may cause harm to others’ interests (this is especially true in contexts where the interests of others are aligned with one’s own), and this type of behavior is thought to be morally unacceptable (Kilduff et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Schein & Gray, 2018). If a person inhibits the motivation to conduct a proscriptive behavior toward others, she/he would be evaluated as morally acceptable (Janoff-Bulman et al., 2009).

Recent studies have applied relationship-regulation theory to moral evaluation research (Anderson et al., 2020; McManus et al., 2020) and have proposed that how people evaluate the morality of actions depends not only on types of actions (prescriptive/altruistic or proscriptive/selfish), but also on the social-relational context in which those actions occur (Earp et al., 2021). In the context where agents should select one recipient to receive the consequence of altruistic behavior in a moral dilemma, the agent who conducts altruistic behavior toward a socially close (vs. socially distant) other individual is evaluated as being more morally acceptable (Law et al., 2022; McManus et al., 2020). However, in the context in which agents should choose one recipient to receive the consequence of selfish behavior in a moral dilemma, the agent who can inhibit or restrain selfish behavior toward a distant stranger (instead of a socially close other person) is evaluated as being more morally acceptable (McManus et al., 2020; Zhan et al., 2020). These studies have demonstrated that in terms of prescriptive (altruistic) behavior, people recognize a positive obligation to help socially close others more than socially distant others (Chalik & Dunham, 2020). However, in the context in which people are required to conduct a proscriptive behavior, the obligations for socially close individuals are reprioritized in moral evaluations and people’s “socially close individual-favoritism” is perceived as inappropriate (Earp et al., 2021; McManus et al., 2020). Individuals recognize a positive obligation not to engage in proscriptive (selfish) behavior toward socially distant others more than toward socially close others. In short, whether the agent directs prescriptive (altruistic) or proscriptive (selfish) actions at a socially distant instead of a socially close other person, he/she would be evaluated as less morally acceptable. Based on these aforementioned studies, two questions needed to be further clarified. First, most studies investigated the effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations from a third-party (i.e., uninvolved observer) perspective (Law et al., 2022; McManus et al., 2020). In these studies, participants were required to read vignettes describing hypothetical scenarios and then evaluate the moral (un)acceptability of the protagonists in the vignettes. To the best of our knowledge, little evidence has directly discussed the effect of the interpersonal relationship on moral evaluations from a second-party perspective (i.e., how participants evaluate the actor’s action when participants act as direct beneficiaries or victims of the consequences of the prescriptive or proscriptive action) (Xie et al., 2022). Unlike the third-party perspective, from a second-party perspective, people could involve the scenarios and experience the consequences of actions for real. In this way, the findings from the second-party perspective are convincing to substantiate prior studies. Second, most of the studies regarding the relationship between interpersonal relationships and moral evaluations employed self-report measurements (i.e., participants were asked to subjectively report the degree of moral acceptability of targets). However, individuals’ subjective ratings that offered explicit responses may be a controlled process, which cannot completely reflect their inner thoughts (Boudreau et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2013). For example, studies have shown that there might be a gap between explicit self-report and implicit (e.g., neural) responses because of potential interferences, such as social desirability responses bias (Cikara & Fiske, 2013; Kaneko et al., 2019; Randall & Fernandes, 1991; Zhang et al., 2021). The development of neuroscience has offered insights into the neural activities (i.e., implicit responses) underlying moral evaluations beyond observable behavior (Gui et al., 2016; Van Bavel et al., 2015). Therefore, we will assess neurophysiological processes during moral evaluations to also clarify the impact of interpersonal relationships on implicit responses that cannot be captured with self-report.

Accordingly, to address these two questions appropriately, we employed the “Social judgment in the modified version of Dictator Game (DG)” task (Park et al., 2020). In a classic DG, allocators have to decide how much, if any, of an endowment to give to another individual (Camerer, 2011; Charness & Haruvy, 2002). If the allocators gave money to recipients (especially those who started with less money than the allocator), they would be evaluated as being altruistic (Li et al., 2019). The major difference between the classic DG and modified DG is that in the modified DG, allocators could decide to take money from the other person. If the allocator took money from recipients for personal gain, they would be considered as selfish (Park et al., 2020). Corresponding to the first question, participants could play the role of recipient in the modified DG, and thus participants could evaluate the allocator’s behavior from the recipient’s perspective (or second-party perspective) (Wu et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2022). Corresponding to the second question, to capture neurophysiological measures of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations, we employed the event-related potential (ERP) technique because ERP can measure neural activities with millisecond resolution and offer insights into the implicit responses, especially the neural dynamics of moral evaluations beyond observable behavior (Gui et al., 2016; Van Bavel et al., 2015). The use of ERP would be helpful in avoiding the potential influence of social desirability responses bias (Pletti et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). For example, participants’ explicit negative evaluations of friends are socially undesirable and might be avoided in the self-report. In the current study, we designed two experiments. In Experiment 1, in aspects of morality, we used a self-report measurement to assess how participants evaluated when their friends (vs. strangers) conducted altruistic and selfish behavior toward participants themselves (vs. someone else). In Experiment 2, we aimed to replicate Experiment 1’s findings and further explored the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations via ERPs.

Experiment 1

The goal of Experiment 1 was to investigate the effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations from the second-party perspective via self-report. Specifically, as mentioned above, the altruistic (prescriptive) and proscriptive (selfish) behaviors were operationalized via the phrases “took money from” and “gave money to” the recipient in the modified DG. According to the definition of moral evaluation (Garrigan et al., 2016), we created a moral dilemma for allocators, in which allocators were forced to select one recipient to receive the consequence of given prescriptive or proscriptive behavior. Here, the participant (her-/himself) and the other person (stranger) were manipulated as the candidate recipients in DG. That is, allocators had to make a choice between the participant and a stranger to be the recipient of behavior’s consequence. Using this manipulation, participants could evaluate the allocator’s behavior from a second-party perspective. Importantly, to achieve the interpersonal relationship manipulation, the target person of the moral evaluation (i.e., the allocator in modified DG) was either the participant’s friend or a stranger. As the dependent variable of the described manipulations, we assessed participants’ moral (un)acceptability ratings in response to altruistic and selfish behavior conducted by the friend or a stranger, toward the participant oneself or another stranger.

As mentioned above, from a third-party perspective, whether the agent directs prescriptive (altruistic) or proscriptive (selfish) actions at a socially distant instead of socially close other, people would evaluate the behavior as less morally acceptable (Law et al., 2022; McManus et al., 2020). From a second-party perspective, people involved similar scenarios and experienced the consequences of actions for real. Therefore, we predicted that this effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations would be similar or even more pronounced from a second-party perspective.

Participants

This study was approved by the Hunan Normal University ethics committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (see Declaration of ethics section). We conducted a priori power analysis for a 2 (allocator) × 2 (allocator’s behavior) × 2 (recipient) within-subject design using G*Power 3.1.9 (F tests, analysis of variance [ANOVA]: repeated-measures, within factor, and the “power = 0.95,” “effect size f = 0.25,” “α = 0.05”). According to the result of this power analysis, 23 participants, at least, could ensure 95% statistical power in the case of small to medium effect sizes (Faul et al., 2007; Mayr et al., 2007; Vazire, 2015; Zhang et al., 2020). We used the same approach in the following experiment to determine our sample size. To reach the minimum sample size criteria (23), we recruited 41 participants (16 men, ages ranging from 19-27 years) from Hunan Normal University. All participants provided written, informed consent before the experiment and were paid at least Chinese Yuan (CNY) 30 for their participation after completing the task.

Cover story and task

The modified version of “Social judgment in DG” (Park et al., 2020) was adopted. As per Fig. 1, the participants (Player A) were informed that they would complete a modified DG with three other people, one of whom was their friend (Player B), and the other two were strangers (Players C and D who did not know each other) to their corresponding friends and themselves. In this task, each participant (Player A) and one stranger (Player D) occupied the role of candidate “recipient.” Each participant’s friend (Player B) and another stranger (Player C) were always assigned to the role of “allocator” (note that all roles were decided by drawing lots ostensibly, although the participant was always drawn to be assigned as the candidate recipient and his/her corresponding friend was always drawn to be assigned as the allocator via pre-programming). “Allocators” (i.e., Players B and C) were endowed with CNY 100 as their starting money, whereas “recipients” (i.e., Players A and D) were endowed with CNY 30Footnote 1. In each round, only one allocator (Players B or C) would be presented with a given behavior (give CNY 10 to or take CNY 10 from one recipient) that was randomly predetermined by a computer. Then, this allocator was required to select one recipient (forced two-option: Player A or D, i.e., moral dilemma for allocators) to receive the given behavior’s consequences in this round.

Interpersonal relationship between each player (including participants and corresponding friends, as well as two strangers) in the cover story. Full line indicates the interpersonal relationship between two people who were friends. Dotted line indicates the interpersonal relationship between two people who were strangers. Participants (Player A) and one stranger (Player D) were assigned to the role of candidate “Recipient” with a starting money of CNY 30, and the participant’s corresponding friend (Player B) and one other stranger (Player C) were assigned to the role of “Allocator” with a starting money of CNY 100. Unknown to participants, Players C and D were two undergraduates serving as confederates

Unbeknownst to the allocators, after observing the allocator’s behavior (gave money to or took money from the participant oneself or another stranger), similar to Rom and Conway (2018)’s measurement questions, participants were required to rate how morally (un)acceptable they had perceived the respective behavior with two different framing items: 1) “How morally acceptable do you evaluate this allocator’s behavior?” and 2) “How morally unacceptable do you evaluate this allocator’s behavior?” The participants rated these items on a 7-point scale (from “1 = not at all” to “7 = very much”). The first item was reverse-coded. These two items were averaged to determine the degree of moral (un)acceptability (r = 0.92). A higher rating score indicated that the allocator’s behavior was evaluated as being less morally acceptable (or, more morally unacceptable). Therefore, for participants, this evaluation task resulted in a 2 (allocator: friend vs. stranger) × 2 (allocator’s behavior: took money vs. gave money) × 2 (recipient: oneself vs. stranger) within-participant design.

Procedure

Based on an interpersonal relationship manipulation from our group (Li et al., 2020a, b), participants were required to bring a same-gender friend with them to participate in the experiment. The participants and friends had to have known each other for more than two years. Two same-gender strangers (who were played by research assistants employed by the laboratory; care was taken that participants and corresponding friends did not know them and were unfamiliar with their names) also took part in the experiment. Before the experiment, participants were informed that the roles of allocators and recipients were randomly determined by drawing lots, although the participants were always selected as the candidate recipients. Each participant also was informed that they and the other three individuals were assigned to separate rooms to complete the experiment together onlineFootnote 2.

After having been escorted to a separate room, to ensure that each participant was sufficiently close to their friend and distant from the other two strangers, they completed the Chinese version of the “Inclusion of Other in the Self” (IOS) scale (Tan et al., 2015), which is a pictorial measure of interpersonal closenessFootnote 3 developed by Aron et al. (1992). It served to assess the closeness between the self and target individuals (i.e., friends and two strangers: one stranger was assigned as the allocator, and the other was assigned as the recipient) on a 7-point pictorial scale from “1= very distant” to “7 = very close.” The assessment results confirmed that participants perceived that their interpersonal relationships were significantly closer with “friends” than with the two “strangers” of the current experiment. See Table S1 in supplementary materials for the participants’ perceived interpersonal relationships assessment.

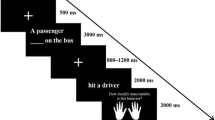

In the formal experiment, each participant received the instruction and was required to repeatedly complete the moral evaluations task (rating how morally [un]acceptable the allocator’s behavior was) in a series of trials. As shown in Fig. 2, at the beginning of each trial, a fixation cross was presented against a black background for 500 ms. Thereafter, the participants viewed the allocator (friends or strangers)’s name (lasted for 2,000 ms) for this given trial. Then, the participants observed that this allocator gave CNY 10 to or took CNY 10 from oneself or a stranger (note that to reduce the cognitive burden of processing the stranger’s [i.e., Player D’s] name, we used the term “someone else” instead). This occurred for 2,000 ms. This was followed by two items assessing the degree of moral (un)acceptability successively (the presented sequence of two items was random across participants) without a time limit. After responding, an inter-trial interval (ITI) was shown for 1,000 ms.

Task sequence in a single trial in Experiment 1

To enhance the experiment’s validity, prior to the experiment, each participant was told that in addition to their base compensation for participation, some trials in this experiment would be randomly selected, and the allocators and recipients would gain or lose the amount of money based on the allocators’ behavior in these selected trials. In reality, there were no real allocators and the allocators’ actions were pre-programmed and randomly presented. The software package E-prime 3.0 (Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) was used for stimulus presentation and data collection. The entire task consisted of 320 trials, divided into eight blocks. The break between the blocks was determined by the participant’s self-pace, and the entire experiment took approximately 32-35 minutes.

After the experiment, we asked all participants about the cover story’s credibility using the question: “Do you believe that you have played the game with real people?” None of them expressed any suspicions. Finally, we told the participants that their friend’s actions were pre-programmed to ensure that this task did not influence their friendship quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics are reported as the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). A repeated-measures ANOVA 2 (allocator) × 2 (allocator’s behavior:) × 2 (recipient) was used to analyze the data. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Partial eta-squared (ƞp2) was reported as a measure of the effect size of the ANOVA. This is where 0.05 represents a small effect, 0.1 represents a medium effect, and 0.2 represents a large effect (Cohen, 1973; Kirk, 1996). Post-hoc tests were corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Results

A higher rating score indicated that the allocator’s behavior was evaluated as being less morally acceptable. For the moral (un)acceptability ratings, the main effect of recipient was significant, F (1,40) = 44.383, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.526. This suggested that choosing the unknown other person as recipient was evaluated as being less morally acceptable (M = 4.344, SD = 1.061) than choosing the participant oneself (M = 3.381, SD = 1.020). The main effect of allocator’s behavior was also significant, F (1,40) = 125.401, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.758, suggesting that participants evaluated “took money” (M = 4.572, SD = 1.00) as being less acceptable than “gave money” (M = 3.154, SD = 1.073). There was no significant main effect of allocator, F (1,40) = 3.627, p = 0.064, ƞp2 = 0.083. In addition to the main effects, significant interactions of allocator × recipient [F (1,40) = 31.981, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.444], allocator × behavior [F (1,40) = 28.617, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.417], and recipient × behavior [F (1,40) = 24.357, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.378] were observed (see the simple effects analysis for two-way interactions in the supplementary materials).

Importantly, there was a significant interaction between allocator × recipient × behavior, F (1,40) = 18.947, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.321. To explore this three-way interaction, we conducted a separate analysis for the “allocator_friend” and “allocator_stranger” conditions. The analysis for the “allocator_friend” condition yielded a significant interaction of recipient × behavior, F (1,40) = 34.931, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.466. Therefore, when friends gave money to a recipient, the participants evaluated it as being less morally acceptable if the recipient was a stranger (Mrecipient_stranger = 4.010 vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 3.152), F (1,40) = 9.380, p = 0.004, ƞp2 = 0.190. When friends decided to take money from a recipient, participants evaluated it as being less morally acceptable when the recipient was a stranger (Mrecipient_stranger = 5.711 vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 3.045), F (1,40) = 62.81, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.61. In contrast, in the case of the “allocator_stranger” condition, the interaction of recipient × behavior was not significant, F (1,40) = 2.128, p = 0.152, ƞp2 = 0.051 (Fig. 3a for the results).

Summary

In accordance with our hypothesis that participants’ moral (un)acceptability ratings for altruistic (prescriptive) and selfish (proscriptive) behavior would be more sensitive to the identities of recipients in cases where the allocator was a friend, our results showed that the friend’s altruistic (prescriptive) and selfish (proscriptive) behavior toward someone else was evaluated as being less morally acceptable than when the friend showed altruistic and selfish behavior toward the participants themselves. However, in the condition where strangers were assigned as the allocator, participants’ moral (un)acceptability ratings for altruistic (prescriptive) and selfish (proscriptive) behaviors were not influenced the recipient identity (someone else vs. participant oneself). In Experiment 1, we have shown how interpersonal relationships affect moral evaluations from the second-party perspective by assessing the subjective ratings. However, little is known about how interpersonal relationships modulate neural responses of moral evaluations. Therefore, we explored the effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations by means of ERP in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we aimed to replicate the behavioral findings of Experiment 1 and further extend them through their neurophysiological underpinnings. Specifically, ERPs were measured when participants observed the choice behavior of the allocators. Prior studies have demonstrated that several ERP components are reflective of outcome evaluation such as medial frontal negativity (MFN) and P3 (Donchin & Coles, 1988; Gehring & Willoughby, 2002; Miltner et al., 1997; Polich, 2007).

In particular, the MFN component is a negative frontocentral ERP deflection, which peaks at approximately 250-350 ms after the outcome’s onset. Its amplitude variation is assumed to reflect early and semi-automatic stimulus evaluation processes (Chen et al., 2018; Hajcak et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2011). The MFN amplitudes reflect the binary evaluation of positive versus negative outcomes (Hauser et al., 2014; Simons, 2010), such that the MFN is reported to be more negative in response to negative (unfavorable/unacceptable) than positive (favorable/acceptable) outcomes (Gu et al., 2011; Hajcak et al., 2006; Pornpattananangkul et al., 2017). Recently, studies have shown that the MFN is an indicator reflecting moral valence evaluations (Scheuble et al., 2021; Scheuble & Beauducel, 2020). For example, Scheuble et al. (2021) have found that the agent’s behavior of negative moral valence (i.e., conflict with moral norms) elicited a more negative MFN.

Following the MFN, the P3 component has been measured to index outcome evaluations at a later and more elaborate processing stage (Gray et al., 2004; Polich, 2007; Wu & Zhou, 2009). It is a positive ERP component that peaks at parietal electrodes along the midline between 350-600 ms after outcome onset. The P3 component is associated with the allocation of attentional resources and outcomes’ motivational salience (Donchin & Coles, 1988; Gray et al., 2004; Kleih et al., 2010; Polich, 2007; Wu & Zhou, 2009; Zhou et al., 2010). However, previous findings about outcome evaluations in P3 are partly inconsistent. For example, several studies have demonstrated that the P3 is larger for positive than for negative outcome (Hajcak et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2018). This suggests that positive outcome signals greater psychological significance and demand for more motivational or attentional resources. Conversely, other studies have shown a larger P3 for negative rather than positive outcomes (Olofsson et al., 2008). These studies suggest that a negative outcome receives preferential access to attentional resources. Moreover, some studies have claimed that the P3 encodes only the outcome magnitude (i.e., large vs. small), but not the outcome valence (i.e., positive vs. negative) (Leng & Zhou, 2010; Sato et al., 2005).

Based on the results in Experiment 1, we again expected to observe an effect of the interpersonal relationship on how the allocators’ choice will be morally evaluated. This effect of interpersonal relationship might also be reflected in neural responses to outcome evaluations. Regarding ERP results predictions, at the early and semiautomatic processing stage (mirrored in the MFN component), we expected that, compared with the “allocator_stranger” condition, in the case of the “allocator_friend” condition, whether following the altruistic or selfish behavior toward someone else (vs. participant oneself), it would evoke a more negative MFN component since a more negative MFN component is associated with a less morally acceptable experience (Scheuble & Beauducel, 2020). However, we had no directional hypothesis for the later responding stage reflected by P3 amplitude variation, because previous research has not reached a consensus about whether the P3 component is sensitive to outcome valence or not.

Participants

As mentioned in Experiment 1, the minimum sample size (n = 23) was calculated by G*Power 3.1.9. To reach this minimum sample size criteria, we recruited 36 participants (19 men, age range 18-25 years). All the participants were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. They all reported no history of traumatic brain injury, brain surgery, mental or neurological diseases, or color blindness. Each EEG participant was paid a remuneration of CNY 50 after completing the experiment. This experiment was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hunan Normal University, Department of Psychology. Notably, the data of two participants were excluded from analysis, as they had more than 30% rejected trials due to EEG artifacts. See the rejection criterion in past studies (Shafir et al., 2018; Sternberg et al., 2021). Finally, the remaining 34 participants’ data (18 men, age range 18-25 years) were included in the final behavioral and ERP analysis.

Procedure

The cover story and procedure of Experiment 2 was almost identical to that of Experiment 1. However, to adapt the task paradigm of Experiment 1 to be used in the ERP experiment, we slightly changed the experimental timeline, number of trials, and outcome presentation from Experiment 1. These changes were implemented to avoid potential confounding factors, such as the different complexity of Chinese characters,Footnote 4 which might cause EEG artifacts in Experiment 2, according to ERP studies investigating outcome evaluations (Hu et al., 2017a, b; Leng & Zhou, 2010; Zhang et al., 2021).

The IOS scale ratings showed that participants perceived interpersonal relationships as being closer with their “friends” than with the two “strangers.” Please see Table S2 for the assessment of participants’ interpersonal relationships. During the EEG data collection, participants were comfortably seated in an electromagnetic shielded room, approximately 75 cm in front of a computer monitor (19-inch LED screen, refresh rate: 60 Hz; resolution: 1,440 × 900 pixels). As shown in Fig. 4, at each trial’s beginning, a fixation cross was presented on a black background for 200 ms. Thereafter, the friend’s or stranger’s name was presented above the fixation cross for 1,000 ms to indicate who would be the “allocator” in this given trial. After a variable interval of 500-1,000 ms, the allocator’s behavior and corresponding recipients was displayed for 1,000 ms: specifically, two squares (1.9° × 1.9° of visual angle) with red and blue borders (red-bordered square represented the participant’s outcome, and blue-bordered square represented the stranger’s outcome) appeared on the left and right sides of the fixation point against the black background. If the allocator gave CNY 10 to the participant in this trial, “+10” would be presented in the red-bordered square in this trial, but if the allocator took CNY 10 from the participant, “−10” would be presented in the red-bordered square in this trial. Alternatively, if the allocator gave CNY 10 to someone else (i.e., another stranger), “+10” would be presented in the blue-bordered square, but if the allocator took CNY 10 from someone else, “−10” would be presented in the blue-bordered square. The two squares with blue and red borders’ positions were counterbalanced across the trials. Thereafter, a blank screen was displayed for 1,000 ms, followed by rating one item regarding moral acceptability (“How morally unacceptable do you evaluate this allocator’s behavior?”) on a 7-point scale (from “1 = not at all” to “7 = very much”), with their index finger (no time limit). Note that one item was removed due to high correlation between two items in Experiment 1 (Barrett et al., 2004; Hawes et al., 2013). The allocator’s behavior that was evaluated as being less morally acceptable would be rated as a higher score. After the rating, a blank screen lasted for 1,000 ms as ITI.

The whole task consisted of 480 trials which were divided into eight blocks. Each outcome consisted of 60 trials. The participants were allowed to take a self-paced break between each block. Unlike Experiment 1, before the formal experiment, participants were given 16 practical trials with two trials per condition. They were thereafter asked whether they understood the experimental procedure. This especially focused on the implications of the different square border colors. The entire experiment took approximately 45-50 minutes.

EEG analysis

Please see Section 2.2 in the supplementary materials for details about EEG recording and analysis. After artifact rejection, no significant differences in artifact-free trials were observed across the experimental conditions (all Fs < 1, all ps > 0.05; Table S3). Mean MFN amplitudes were extracted between 280 and 340 ms, and mean P3 amplitudes were extracted between 350 and 500 ms based on visual inspection of the grand-averaged ERPs and based on prior studies (Hu et al., 2017a, b; Li, Liu, et al., 2020a; Luck & Gaspelin, 2017; Yang et al., 2018). In particular, regarding the MFN measurement, Williams et al. (2020) recently suggested that the mean amplitudes measure is the most appropriate method for feedback-related component quantification. According to the topographical distribution (Figs. 5b and 6b) and representative electrodes commonly used in previous studies (Liu et al., 2021; Severo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022), the MFN was calculated as the average of Fz and FCz electrode sites, and the P3 was calculated as the average of CPz and Pz electrode sites. The mean amplitude values were extracted and averaged for all the selected electrode sites per the ERP component. The statistical analysis method was identical to that used in Experiment 1.

a Grand-average ERP waveforms at the Fz and FCz electrode sites. Grey bars highlight the time window of the MFN (280-340 ms). b Differences in MFN (MFN effect) voltage topographies between the conditions indicating “gave money to/took money from “someone else” and “gave money to/took money from participants” in case of “allocator_friend” trials and “allocator_stranger” conditions, separately. c MFN mean amplitudes (in μV) in each condition. Note: Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

a Grand-average ERP waveforms at the CPz and Pz electrode sites. Grey bars highlight the time window of the P3 (350-500 ms). b Topographies voltage distribution of P3 in each condition. c Bar graphs showing P3 mean amplitudes (in μV) in each condition. Note: Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Neural-behavioral correlation

To explore the relationship between subjective ratings and neural activities, Pearson’s correlation (r, two-sided) analysis was calculated between subjective ratings and ERP components according to past literatures (Hu & Mai, 2021; Santesso et al., 2005).

Results

Subjective ratings of moral acceptability

Replicating the results in Experiment 1, a higher rating score indicated that the allocator’s behavior was evaluated as being less morally acceptable. The analysis of the moral acceptability degree ratings showed a significant main effect of recipient, F (1,33) = 52.097, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.612, suggesting that compared with choosing the participant oneself as the recipients (M = 3.404, SD = 0.953), choosing someone else as the recipient was evaluated as being less acceptable (M = 4.218, SD = 1.053). The main effect of behavior was also observed, F (1,33) = 65.985, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.667. This indicated that relative to “gave money” (M = 3.276, SD = 0.862), the participants evaluated “took money” (M = 4.346, SD = 1.144) as being less acceptable. The main effect of allocator was not observed, F (1,33) = 0.109, p = 0.744, ƞp2 = 0.003. Moreover, interactions of allocator × recipient [F (1,33) = 48.898, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.597], and allocator × behavior [F (1,33) = 9.051, p = 0.005, ƞp2 = 0.215] were observed. The interaction of recipient × behavior approached significance, F (1,33) = 3.929, p = 0.056, ƞp2 = 0.106 (see the simple effects analysis for two-way interactions in the supplementary materials).

The three-way interaction of allocator × recipient × behavior was significant, F (1,33) = 5.553, p = 0.025, ƞp2 = 0.114. The follow-up analysis showed that the interaction of recipient × behavior in the “allocator_friend” condition was significant, F (1,33) = 7.122, p = 0.012, ƞp2 = 0.178, suggesting that when friends gave money to someone else instead of the participant oneself, the participants rated this as being less morally acceptable (Mrecipient_stranger = 4.027 vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 2.884), F (1,33) = 28.03, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.459. When friends took money from someone else instead of the participant oneself, the participants experienced this as being less morally acceptable (Mrecipient_stranger = 5.221 vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 3.031), F (1,33) = 46.54, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.585. In contrast, the interaction of recipient × behavior in the “allocator _stranger” condition was not significant, F (1,33) = 0.032, p = 0.860, ƞp2 = 0.001 (Fig. 3b). Thus, Experiment 2 showed the same pattern of behavioral results as Experiment 1.

ERP results

MFN (280-340 ms)

As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the main effect of the recipient was significant, F (1,33) = 15.137, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.314. This suggests that the MFN component was more negative when the recipient was a stranger than the participant oneself (Mrecipient_stranger = 0.532 μV vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 1.507 μV). The main effect of behavior also was significant, F (1,33) = 7.572, p = 0.010, ƞp2 = 0.187, suggesting that “took money” evoked a more negative MFN amplitudes than “gave money” (Mselfish behavior = 0.617 μV vs. Maltruistic behavior = 1.421 μV). There was no main effect of allocator, F (1, 33) = 0.635, p = 0.431, ηp2 = 0.019. In addition, a significant interaction of allocator × recipient was observed [F (1,33) = 7.633, p = 0.009, ƞp2 = 0.188]. However, the allocator × behavior [F (1,33) = 0.718, p = 0.403, ƞp2 = 0.021], and recipient × behavior [F (1,33) = 0.991, p = 0.327, ƞp2 = 0.029] interactions were not significant (see the simple effects analysis for two-way interactions in the supplementary materials).

Critically, there was a three-way interaction of the allocator × recipient × behavior, F (1, 33) = 4.227, p = 0.048, ηp2 = 0.114. Separate analyses of MFN amplitudes for the “allocator_friend” and “allocator_stranger” conditions were conducted to explore this interaction: The interaction of the recipient × behavior in the “allocator_friend” condition was significant, F (1,33) = 5.853, p = 0.021, ƞp2 = 0.151. When friends decided to give money to someone else instead of the participants, the MFN was more negative (Mrecipient_stranger = 0.777 μV vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 1.733 μV), F (1,33) = 5.17, p = 0.030, ƞp2 = 0.135. When friends took money from someone else instead of the participants, the MFN was more negative (Mrecipient_stranger = −0.472 vs. Mrecipient_oneself = 1.680 μV), F (1,33) = 29.12, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.469. Conversely, no significant interaction of the recipient × behavior in the “allocator_stranger” condition emerged, F (1,33) = 0.201, p = 0.657, ƞp2 = 0.006. This was reminiscent of the pattern of subjective ratings for moral unacceptability.

Albeit both friends’ altruistic and selfish behavior was sensitive to identities of recipients, the effect sizes were largely different. In order to check whether behavior types are differently weighed in different interpersonal relationship contexts, we further analyzed the MFN effect (i.e., subtracting the MFN induced by “recipient_oneself” condition from that induced by “recipient_stranger” condition) following the allocator’s altruistic and selfish behavior. A repeated-measures ANOVA 2 (allocator: friend vs. stranger) × 2 (allocator’s behavior: took vs. gave money) was created to analyze the MFN effect. The results demonstrated that the main effect of the allocator was significant, F (1,33) = 7.631, p = 0.009, ƞp2 = 0.188, demonstrating that the MFN effect in the condition of “allocator_friend” (M = −1.554 μV, SD = 2.385) was stronger than that in the condition of “allocator_stranger” (M = −0.395 μV, SD = 2.687). The main behavior was not significant, F (1,33) = 0.997, p = 0.325, ƞp2 = 0.029. Importantly, we found an interaction of allocator × behavior, F (1,33) = 4.215, p = 0.048, ƞp2 = 0.113. In the case of “allocator _friend” trials, the MFN effect for selfish behavior (M = −2.152 μV, SD = 2.324) was stronger than that for altruistic behavior (M = −0.957 μV, SD = 2.453), F (1,33) = 5.861, p = 0.021, ƞp2 = 0.124. However, in the case of “allocator_stranger” trials, the MFN effect following the selfish and altruistic behavior was not significant, F (1,33) = 0.204, p = 0.659, ƞp2 = 0.005.

P3 (350-500 ms)

As demonstrated in Fig. 6, the following significant main effects were observed: allocator [F (1,33) = 5.328, p = 0.027, ƞp2 = 0.139, suggesting that the P3 evoked by friends (M = 7.774 μV, SD = 3.373) was larger than that evoked by strangers (M = 7.321 μV, SD = 3.509)], recipient [F (1,33) = 37.606, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.533, demonstrating that the P3 elicited by the participants (M = 8.100 μV, SD = 3.418) was larger than that evoked by someone else (M = 6.996 μV, SD = 3.461)], and allocator‘s behavior [F (1,33) = 21.569, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.395, demonstrating that the P3 elicited by altruistic behavior (M = 8.079 μV, SD = 3.434) was larger than that evoked by selfish behavior (M = 7.017 μV, SD = 3.446)].

Moreover, the interactions of allocator × recipient [F (1,33) = 5.180, p = 0.029, ƞp2 = 0.136], and recipient × behavior [F (1,33) = 10.104, p = 0.003, ƞp2 = 0.234] were significant. First, a follow-up simple effects analysis was conducted to explore the interaction of allocator × recipient. This showed that when participants were the recipients, the P3 was sensitive to the identity of the allocator, F (1,33) = 8.910, p = 0.005, ƞp2 = 0.255; whereas when strangers were the recipients, the P3 was insensitive to the identity of the allocator, F (1,33) = 0.140, p = 0.713, ƞp2 = 0.002. Second, we explored the interaction of recipient × behavior and found that when the recipients were the participants, P3 was sensitive to the behavior, F (1,33) = 31.220, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.345; whereas when the recipients were someone else, P3 was insensitive to the behavior, F (1,33) = 1.280, p = 0.267. However, the interactions of allocator × behavior [F (1,33) = 2.538, p = 0.121, ƞp2 = 0.071] and allocator × recipient × behavior [F (1,33) = 0.194, p = 0.663, ƞp2 = 0.006] were not significant.

Correlation analysis between MFN amplitudes and subjective ratings

Reminiscent of the similar interactions pattern between MFN amplitudes patterns and subjective ratings, a Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted. This served to further explore the association between the ∆MFN to recipients (i.e., MFN evoked by recipients_stranger minus that which was evoked by recipients_oneself) and ∆subjective ratings to the recipients (subjective ratings for recipients_stranger minus ratings for recipients_oneself). This analysis was conducted in the “allocator_friend” and “allocator_stranger” conditions, respectively. The results revealed that in the condition where friends were assigned as allocators, the correlation was significant (r = −0.443, p = 0.009, 95% confidence interval [CI] [−0.656, −0.149]; Fig. 7). However, no correlation was observed in the “allocator_stranger” condition (r = 0.059, p = 0.741). In addition, the Steiger’s z test (Steiger, 1980) conducted to compare correlations within a sample indicated that the “allocator_friend” condition’s correlation was significantly different from the “allocator_stranger” condition’s correlation (z = −2.21, p < 0.05).

Scatter plots and regression lines of the ∆MFN responses to recipients (i.e., MFN mean values evoked by someone else minus those evoked by participants) as a function of the ∆moral unacceptability ratings of recipients (i.e., subjective ratings involving someone else minus subjective ratings involving participants) in the “allocator_friend” condition

Summary and discussion

First, the moral acceptability ratings in Experiment 2 replicated the results in Experiment 1. Second, the ERP results showed that interpersonal relationships modulated moral evaluations, as mirrored by MFN amplitude variation. Whether following friends’ altruistic or selfish behavior, the MFN elicited by behavior directed at someone else instead of participants was more negative. A more negative MFN amplitude is associated with an unfavorable or unacceptable outcome experience (Gangl et al., 2017; Hu & Mai, 2021; Li et al., 2021). Hence, from the neural perspective, friends’ proscriptive and prescriptive behavior directed to someone else (instead of participants) were processed as being more unacceptable and this effect occurred at the early processing stage. However, this effect did not emerge in the condition where strangers were assigned as the allocator. Furthermore, relative to friends’ altruistic behavior, the MFN effect was more negative following friends’ selfish behavior. It suggested that as compared with friends’ altruistic behavior, the participants were more sensitive to friends’ selfish behavior toward strangers. However, regarding the P3 component, we did not observe an effect of interpersonal relationships on the interaction allocators’ behavior × recipients, suggesting that the effect of interpersonal relationship on moral evaluations did not reflect on the P3 component.

Discussion

This study examined how people evaluated their friends’ (vs. strangers’) behavior in terms of prescriptive and proscriptive morality by providing moral (un)acceptability ratings (Experiment 1 and 2) and ERP (Experiment 2) evidence. Across two experiments, the moral acceptability ratings indicated that in the condition where participants’ friends were assigned as the allocators, the allocators’ altruistic and selfish behavior toward someone else were evaluated as being less morally acceptable than when the respective behavior was directed toward the participants themselves. By contrast, in the condition where strangers were allocators, the moral (un)acceptability rating for allocators’ behavior was not affected by the identities of recipients. In Experiment 2, the ERP results revealed that the interpersonal relationship influenced moral evaluations, as was mainly reflected in MFN amplitude variation.

Concerning the subjective ratings of moral acceptability, both Experiments 1 and 2 supported our predictions. From the recipient’s perspective, this finding was in accordance with previous research. These previous studies have indicated that an agent who conducts altruistic (prescriptive) and selfish (proscriptive) actions directed at a socially distant (vs. a socially close) individual one is evaluated as being less morally acceptable (Law et al., 2022; McManus et al., 2020).

With regard to the ERP results, we detailed the discussions at the early (i.e., mirrored by MFN) and later (i.e., mirrored by P3) outcome evaluation processing stages: at the earlier and semi-automatic processing stage, which is represented by the MFN (Gangl et al., 2017; Hu & Mai, 2021), the interaction between the allocators’ behavior × recipients was moderated by the allocator. Consistent with our prediction about the MFN, we found that relative to the condition where the allocator was a stranger, in the condition where the allocator was a friend, following altruistic and selfish behavior, the MFN was sensitive to recipients. To be more specific, when the friend’s altruistic (prescriptive) or selfish (proscriptive) behavior was directed toward someone else (vs. participant oneself), it elicited a more negative-going MFN. Combined with the correlation analysis, this finding repeatedly reflects that friend’s altruistic and selfish behavior toward someone else are less morally acceptable for participants. Interestingly, participants exhibited a stronger MFN effect following their friends’ selfish behavior relative to friends’ altruistic behavior. This suggested that compared with friends’ altruistic behavior directed at strangers, participants experience friends’ selfish behavior directed at strangers as being less morally acceptable. Although this finding was not predicted, it could be explained by previous evidence. Proscriptive (selfish) actions are heavily weighted in moral evaluations of others (Anderson et al., 2020; Van Bavel et al., 2015), and individuals think a morally acceptable individual should, at a minimum, not cause harm to an unknown person (Anderson et al., 2020; Zhan et al., 2020). People tend to think their friends to be morally good (Law et al., 2022; Moisuc & Brauer, 2019; Parker & Seal, 1996). Naturally, participants evaluated it as being less acceptable when friends did harm to others, especially to strangers. This could explain why, as compared with the friends’ altruistic behavior, a more pronounced MFN effect was generated following friends’ selfish behavior toward strangers. Moreover, it is worth noting that the current MFN finding is supported by previous findings. These findings also suggest that moral evaluations occurs at the earlier processing stage captured by ERPs (Decety & Cacioppo, 2012).

At the later and controlled responding stage represented by P3, we did not find a modulation of the allocator in the interaction of allocators’ behavior × recipients. The absent effect of interpersonal relationship on P3 amplitudes is supported by past evidence reporting that P3 amplitudes were not sensitive to interpersonal relationship manipulations during outcome evaluation (Li et al., 2021;Wu et al., 2011 ; Wu & Zhou, 2009). These studies have proposed as a possible explanation that the information regarding this may have already been coded by the preceding MFN. Therefore, the neural system does not recode it on the P3 (Wu et al., 2011; Wu & Zhou, 2009).

Taken together, from a second-party perspective, our findings support the relationship-regulation theory in moral psychology research which proposes that the moral evaluations about actions depends not only on the action types (i.e., altruistic/prescriptive or selfish/proscriptive) but also on the social-relational contexts in which these occur (Earp et al., 2021). The moral evaluations of behavior are contingent on the interpersonal relationship between the actors and receivers of behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the power analysis for the sample size was calculated for the within-subjects effects but not for the correlations. Hence, the correlation between MFN components and moral acceptability ratings may be underpowered. Second, the allocator and their behavior in this study were randomly decided, which were different from the everyday experiences and might affect the ecological validity. The future directions are as follows: first, we could further examine how participants respond if the other two strangers (i.e., Players C and D in this study) are manipulated as a pair of friends. Second, we only assigned the candidate recipients as participants or strangers. However, previous studies have suggested that people evaluate a friend more negatively when their friends behave more altruistically toward another friend (Barakzai & Shaw, 2018; Krems et al., 2021). In future studies, we can further explore the effects of other recipients’ identities.

Conclusions

The goal of this study was to examine the effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations by providing moral acceptability ratings and electrophysiological evidence. The interpersonal relationship affected both the subjective ratings and MFN amplitude variation in moral evaluations. In summary, from the second-party perspective, individuals evaluated it as being less morally acceptable when their friends select the other unknown person (instead of the individual oneself) as the recipients of proscriptive and prescriptive behavior in a moral dilemma. This effect of interpersonal relationships on moral evaluations occurred at an earlier and semiautomatic processing stage in the brains.

Data availability

All data generated for this study are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/pufy5.

Notes

Note: In reality, all behavior conducted by a “friend (Player B)” or a “stranger (Player C)” was pre-programed and predetermined, and their corresponding friend simultaneously completed another task unrelated to the experiment, which also took approximately 30-35 minutes, in separate rooms.

3 Note: The IOS scale consists of seven pairs of circles, with one circle representing the self and the other circle representing a target person. The degree of the circles’ intersection signifies the degree of social closeness (range 1-7). The participants choose a suitable pair of circles to describe their relationship with each target person. Higher IOS score indicates an increasing level of overlap between the self and target person (i.e., a socially closer relationship) (Aron et al., 1992; Wu et al., 2011; Zhan et al., 2016; Zhan et al., 2017).

Note: To rule out potentially confusing factors, such as different Chinese characters (i.e., ¨拿走” (took), ¨给予” (gave), “你自己” (you) and “其他人” (someone else),” we modified these words as ¨−, +¨ and by using squares with red/blue borders.

References

Anderson, R. A., Crockett, M. J., & Pizarro, D. A. (2020). A theory of moral praise. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(9), 694–703.

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the Structure of Interpersonal Closeness. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612.

Barakzai, A., & Shaw, A. (2018). Friends without benefits: When we react negatively to helpful and generous friends. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(5), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.05.004

Barrett, G., Smith, S. C., & Wellings, K. (2004). Conceptualisation, development, and evaluation of a measure of unplanned pregnancy. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(5), 426. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.014787

Boudreau, C., McCubbins, M. D., & Coulson, S. (2009). Knowing when to trust others: An ERP study of decision making after receiving information from unknown people. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(1), 23–34.

Camerer, C. F. (2011). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton University Press.

Chalik, L., & Dunham, Y. (2020). Beliefs About Moral Obligation Structure Children's Social Category-Based Expectations. Child Development, 91(1), e108–e119. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13165

Charness, G., & Haruvy, E. (2002). Altruism, equity, and reciprocity in a gift-exchange experiment: An encompassing approach. Games and Economic Behavior, 40(2), 203–231.

Chen, M., Zhao, Z., & Lai, H. (2018). The time course of neural responses to social versus non-social unfairness in the ultimatum game. Social Neuroscience, 14(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2018.1486736

Cikara, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2013). Their pain, our pleasure: Stereotype content and schadenfreude. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1299(1), 52–59.

Cohen, J. (1973). Eta-squared and partial eta-squared in fixed factor anova designs. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33(1), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447303300111

Cushman, F. (2015). From moral concern to moral constraint. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 58–62.

Decety, J., & Cacioppo, S. (2012). The speed of morality: A high-density electrical neuroimaging study. Journal of Neurophysiology, 108(11), 3068–3072.

Donchin, E., & Coles, M. G. (1988). Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(3), 357–374.

Earp, B. D., McLoughlin, K. L., Monrad, J. T., Clark, M. S., & Crockett, M. J. (2021). How social relationships shape moral wrongness judgments. Nature Communications, 12(1), 5776. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26067-4

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Gangl, K., Pfabigan, D. M., Lamm, C., Kirchler, E., & Hofmann, E. (2017). Coercive and legitimate authority impact tax honesty: Evidence from behavioral and ERP experiments. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 12(7), 1108–1117.

Garrigan, B., Adlam, A. L., & Langdon, P. E. (2016). The neural correlates of moral decision-making: A systematic review and meta-analysis of moral evaluations and response decision judgements. Brain and Cognition, 108, 88–97.

Gehring, W. J., & Willoughby, A. R. (2002). The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science, 295(5563), 2279–2282.

Gray, H. M., Ambady, N., Lowenthal, W. T., & Deldin, P. (2004). P300 as an index of attention to self-relevant stimuli. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(2), 216–224.

Gu, R., Wu, T., Jiang, Y., & Luo, Y. J. (2011). Woulda, coulda, shoulda: The evaluation and the impact of the alternative outcome. Psychophysiology, 48(10), 1354.

Gui, D. Y., Gan, T., & Liu, C. (2016). Neural evidence for moral intuition and the temporal dynamics of interactions between emotional processes and moral cognition. Social Neuroscience, 11(4), 380.

Hajcak, G., Moser, J. S., Holroyd, C. B., & Simons, R. F. (2006). The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biological Psychology, 71(2), 148–154.

Hauser, T. U., Iannaccone, R., Stämpfli, P., Drechsler, R., Brandeis, D., Walitza, S., & Brem, S. (2014). The feedback-related negativity (FRN) revisited: New insights into the localization, meaning and network organization. NeuroImage, 84(1), 159–168.

Hawes, S., Byrd, A., Henderson, C., Gazda, R., Burke, J., Loeber, R., & Pardini, D. (2013). Refining the parent-reported inventory of callous-unemotional traits in boys with conduct problems. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034718

Hu, X., & Mai, X. (2021). Social value orientation modulates fairness processing during social decision-making: Evidence from behavior and brain potentials. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(7), 670–682. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab032

Hu, J., Li, Y., Yin, Y., Blue, P. R., Yu, H., & Zhou, X. (2017a). How do self-interest and other-need interact in the brain to determine altruistic behavior? NeuroImage, 157, 598–611.

Hu, X., Xu, Z., & Mai, X. (2017b). Social value orientation modulates the processing of outcome evaluation involving others. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(11), 1730–1739.

Hu, Y., et al. (2022). Neuroscience of moral decision making. In S. Della Sala (Ed.), Encyclopedia of behavioral neuroscience (2nd ed, pp. 481–495). Elsevier.

Janoff-Bulman, R., Sheikh, S., & Hepp, S. (2009). Proscriptive versus prescriptive morality: Two faces of moral regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013779

Kaneko, D., Hogervorst, M., Toet, A., van Erp, J. B., Kallen, V., & Brouwer, A.-M. (2019). Explicit and implicit responses to tasting drinks associated with different tasting experiences. Sensors, 19(20), 4397.

Kilduff, G. J., Galinsky, A. D., Gallo, E., & Reade, J. J. (2016). Whatever it takes to win: Rivalry increases unethical behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 59(5), 1508–1534.

Kirk, R. E. (1996). Practical significance: A concept whose time has come. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(5), 746–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164496056005002

Kleih, S. C., Nijboer, F., Halder, S., & Kübler, A. (2010). Motivation modulates the P300 amplitude during brain-computer interface use. Clinical Neurophysiology Official Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(7), 1023–1031.

Krems, J. A., Williams, K. E. G., Aktipis, A., & Kenrick, D. T. (2021). Friendship jealousy: One tool for maintaining friendships in the face of third-party threats? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 977–1012. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000311

Law, K. F., Campbell, D., & Gaesser, B. (2022). Biased benevolence: The perceived morality of effective altruism across social distance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(3), 426–444.

Leng, Y., & Zhou, X. L. (2010). Modulation of the brain activity in outcome evaluation by interpersonal relationship: An ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 48(2), 448–455.

Li, J., Li, A., Sun, Y., Li, H. E., Liu, L., Zhan, Y., ... Zhong, Y. (2019). The effect of preceding self-control on prosocial behaviors: The moderating role of awe. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00682

Li, J., Liu, L., Sun, Y., Fan, W., Li, M., & Zhong, Y. (2020a). Exposure to money modulates neural responses to outcome evaluations involving social reward. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(1), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa019

Li, J., Sun, Y., Li, M., Li, H., & e., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2020b). Social distance modulates prosocial behaviors in the gain and loss contexts: An event-related potential (ERP) study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 150, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.02.003

Li, J., Xu, N., & Zhong, Y. (2021). Monetary payoffs modulate reciprocity expectations in outcome evaluations: An event-related potential study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 53(3), 902–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15100

Liu, S. Q., Hu, X. M., & Mai, X. Q. (2021). Social distance modulates outcome processing when comparing abilities with others. Psychophysiology, 58(5), 13. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13798

Lu, J. G., Zhang, T., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2018). On the distinction between unethical and selfish behavior. In K. Gray & J. Graham (Eds.), Atlas of moral psychology: Mapping good and evil in the mind (pp. 465–474). Guilford Press.

Luck, S., & Gaspelin, N. (2017). How to get statistically significant effects in any ERP experiment (and Why You Shouldn’t). Psychophysiology, 54(1), 146–157.

Mayr, S., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Faul, F. (2007). A short tutorial of G*Power. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3(2), 51–59.

McManus, R. M., Kleiman-Weiner, M., & Young, L. (2020). What we owe to family: The impact of special obligations on moral judgment. Psychological Science, 31(3), 227–242.

Miltner, W. H. R., Braun, C. H., & Coles, M. G. H. (1997). Event-related brain potentials following incorrect feedback in a time-estimation task: Evidence for a “Generic” neural system for error detection. Journal of Cogntive Neuroscience, 9(6), 788–798.

Moisuc, A., & Brauer, M. (2019). Social norms are enforced by friends: The effect of relationship closeness on bystanders’ tendency to confront perpetrators of uncivil, immoral, and discriminatory behaviors. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(4), 824–830.

Noval, L. J., & Stahl, G. K. (2017). Accounting for proscriptive and prescriptive morality in the workplace: The double-edged sword effect of mood on managerial ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(3), 589–602.

Olofsson, J., Nordin, S., Sequeira, H., & Polich, J. (2008). Affective picture processing: An integrative review of ERP findings. Biological Psychology, 77(3), 247–265.

Park, B., Fareri, D., Delgado, M., & Young, L. (2020). The role of right temporo-parietal junction in processing social prediction error across relationship contexts. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(8), 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa072

Parker, J. G., & Seal, J. (1996). Forming, losing, renewing, and replacing friendships: Applying temporal parameters to the assessment of children's friendship experiences. Child Development, 67(5), 2248–2268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01855.x

Perry, A., Rubinsten, O., Peled, L., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2013). Don't stand so close to me: A behavioral and ERP study of preferred interpersonal distance. NeuroImage, 83, 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.042

Pletti, C., Decety, J., & Paulus, M. (2019). Moral identity relates to the neural processing of third-party moral behavior. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14(4), 435–445.

Polich, J. (2007). Updating P300: An integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(10), 2128–2148.

Pornpattananangkul, N., Nadig, A., Heidinger, S., Walden, K., & Nusslock, R. (2017). Elevated outcome-anticipation and outcome-evaluation ERPs associated with a greater preference for larger-but-delayed rewards. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 17(3), 625–641.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(11), 805–817.

Rom, S. C., & Conway, P. (2018). The strategic moral self: Self-presentation shapes moral dilemma judgments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 24–37.

Santesso, D. L., Segalowitz, S. J., & Schmidt, L. A. (2005). ERP correlates of error monitoring in 10-year olds are related to socialization. Biological Psychology, 70(2), 79–87.

Sato, A., Yasuda, A., Ohira, H., Miyawaki, K., Nishikawa, M., Kumano, H., & Kuboki, T. (2005). Effects of value and reward magnitude on feedback negativity and P300. NeuroReport, 16(4), 407–411.

Schein, C., & Gray, K. (2018). The theory of dyadic morality: Reinventing moral judgment by redefining harm. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 32–70.

Scheuble, V., & Beauducel, A. (2020). Individual differences in ERPs during deception: Observing vs. demonstrating behavior leading to a small social conflict. Biological Psychology, 150, 107830.

Scheuble, V., Mildenberger, M., & Beauducel, A. (2021). The P300 and MFN as indicators of concealed knowledge in situations with negative and positive moral valence. Biological Psychology, 162, 108093.

Severo, M. C., Paul, K., Walentowska, W., Moors, A., & Pourtois, G. (2020). Neurophysiological evidence for evaluative feedback processing depending on goal relevance. NeuroImage, 215, 116857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116857

Shafir, R., Zucker, L., & Sheppes, G. (2018). Turning off hot feelings: Down-regulation of sexual desire using distraction and situation-focused reappraisal. Biological Psychology, 137, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.07.007

Simons, R. (2010). The way of our errors: Theme and variations. Psychophysiology, 47(1), 1–14.

Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87(2), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.87.2.245

Sternberg, N., Luria, R., & Sheppes, G. (2021). Mental logout: Behavioral and neural correlates of regulating temptations to use social media. Psychological Science, 32(10), 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211001316

Tan, Q., Zhan, Y., Gao, S., Fan, W., Chen, J., & Zhong, Y. (2015). Closer the relatives are, more intimate and similar we are: Kinship effects on self-other overlap. Personality & Individual Differences, 73(73), 7–11.

Van Bavel, J. J., FeldmanHall, O., & Mende-Siedlecki, P. (2015). The neuroscience of moral cognition: From dual processes to dynamic systems. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 167–172.

Vazire, S. (2015). Editorial. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615603955

Wang, A., Zhu, L., Lyu, D., Cai, D., Ma, Q., & Jin, J. (2022). You are excusable! Neural correlates of economic neediness on empathic concern and fairness perception. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 22(1), 99–111.

Williams, C., Ferguson, T., Hassall, C., Abimbola, W., & Krigolson, O. (2020). The ERP, frequency, and time–frequency correlates of feedback processing: Insights from a large sample study. Psychophysiology, 58(2), e13722. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13722

Wu, Y., & Zhou, X. (2009). The P300 and reward valence, magnitude, and expectancy in outcome evaluation. Brain Research, 1286, 114–122.

Wu, Y., Leliveld, M. C., & Zhou, X. (2011). Social distance modulates recipient's fairness consideration in the dictator game: An ERP study. Biological Psychology, 88(2), 253–262.

Xie, E., Liu, M., Liu, J., Gao, X., & Li, X. (2022). Neural mechanisms of the mood effects on third-party responses to injustice after unfair experiences. Human Brain Mapping, (in press). https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25874

Yang, Z., Sedikides, C., Gu, R., Luo, Y. L. L., Wang, Y., & Cai, H. (2018). Narcissism and risky decisions: A neurophysiological approach. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 13(8), 889–897.

Yuan, B., Tolomeo, S., Yang, C., Wang, Y., & Yu, R. (2021). The tDCS effect on prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab067

Zhan, Y., Chen, J., Xiao, X., Li, J., Yang, Z., Wei, F., & Zhong, Y. (2016). Reward promotes self-face processing: An event-related potential study. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 735.

Zhan, Y., Xiao, X., Chen, J., Li, J., Wei, F., & Zhong, Y. (2017). Consciously over unconsciously perceived rewards facilitate self-face processing: An ERP study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 7836.

Zhan, Y., Xiao, X., Tan, Q., Li, J., Fan, W., Chen, J., & Zhong, Y. (2020). Neural correlations of the influence of self-relevance on moral decision-making involving a trade-off between harm and reward. Psychophysiology, 57(9), e13590. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13590

Zhang, H., Zhang, M., Lu, J., Zhao, L., Zhao, D., Xiao, C., ... Luo, W. (2020). Interpersonal relationships modulate outcome evaluation in a social comparison context: The pain and pleasure of intimacy. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 20(1), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-019-00756-6

Zhang, H., Gu, R., Yang, M., Zhang, M., Han, F., Li, H., & Luo, W. (2021). Context-based interpersonal relationship modulates social comparison between outcomes: An event-related potential study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa167

Zhou, Z., Yu, R., & Zhou, X. (2010). To do or not to do? Action enlarges the FRN and P300 effects in outcome evaluation. Neuropsychologia, 48(12), 3606–3613.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Daniela M. Pfabigan (University of Oslo) for her thoughtful comments on this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32000769), the major project of the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 17ZDA326), the youth project of the Social Science Fund of Hunan Province (No. 19YBQ080), and the youth project of the Natural Science Fund of Hunan Province (No. 2021JJ40337).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in Experiments 1 and 2 were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments and comparable ethical standards. The study obtained ethical approval from the Internal Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, P. R. China (The ethics approval ref. number of research: 2020-068).

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Li, M., Sun, Y. et al. Interpersonal relationships modulate subjective ratings and electrophysiological responses of moral evaluations. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 23, 125–141 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-022-01041-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-022-01041-9