Abstract

Face perception is widely believed to involve integration of facial features into a holistic perceptual unit, but the mechanisms underlying this integration are relatively unknown. We examined whether perceptual grouping cues influence a classic marker of holistic face perception, the “composite-face effect.” Participants made same–different judgments about a cued part of sequentially presented chimeric faces, and holistic processing was indexed as the degree to which the task-irrelevant face halves impacted performance. Grouping was encouraged or discouraged by adjusting the backgrounds behind the face halves: Although the face halves were always aligned, their respective backgrounds could be misaligned and of different colors. Holistic processing of face, but not of nonface, stimuli was significantly reduced when the backgrounds were misaligned and of different colors, cues that discouraged grouping of the face halves into a cohesive unit (Exp. 1). This effect was sensitive to stimulus orientation at short (200 ms) but not at long (2,500 ms) encoding durations, consistent with the previously documented temporal properties of the holistic processing of upright and inverted faces (Exps. 2 and 3). These results suggest that grouping mechanisms, typically involved in the perception of objecthood more generally, might contribute in important ways to the holistic perception of faces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One of the most robust and commonly used markers of holistic face processing is the composite effect (e.g., Richler, Cheung, & Gauthier, 2011; Schiltz, Dricot, Goebel, & Rossion, 2010; Susilo, Crookes, McKone, & Turner, 2009; Young, Hellawell, & Hay, 1987). This effect, also known as the composite illusion, refers to conditions in which the top and bottom halves of different faces are combined to make a chimeric face, perceptually fusing together to create a new hybrid identity. As a consequence, observers experience difficulty making a perceptual judgment about the top or bottom half of such faces without being influenced by the other, task-irrelevant half. Participants are released from fusing the face parts together into a holistic gestalt when the parts are misaligned or rotated by 180° (Young et al., 1987). In the case of misalignment, the release from otherwise obligatory holistic processing is generally assumed to occur because of the disruption of the prototypical facial configuration to which face-specific mechanisms are tuned.

Mechanistically, one reason that misalignment disrupts holistic face perception might be because it disrupts perceptual grouping of the face parts. If face perception is governed by the same gestalt grouping principles that apply to nonface objects, misaligning the face parts should impact on the integrity of a face’s “objecthood”—that is, the strength with which the parts are grouped into a single entity. For example, the disruption to the global contour of the face with misalignment of the top and bottom parts would be expected to weaken the grouping of these parts. Notably, in aligned chimeric faces, the continuity in the global contour of the top and bottom parts would facilitate the grouping of these parts. Perceptual grouping cues, such as good continuity, are often thought of as the tension or “glue” that holds perceptual features together to form objects. Currently, it is unclear whether a disruption to perceptual grouping cues can facilitate a release from holistic processing even, perhaps, when the face parts themselves are aligned, and thus the face configuration remains intact.

In previous studies documenting the misalignment-driven attenuation of holistic face processing, the disruption to the configuration of the facial features has been confounded with a potential disruption to the perceptual grouping of the parts. Thus, it has been unclear from these studies whether a weakening in the perceptual grouping of the face parts, independent of their physical misalignment, contributes to the disruption of holistic face processing. One possibility is that the effect of misalignment stems from a weakening of the perceptual grouping of the face parts, which thereby allows the top and bottom halves of the face to be perceived more independently. This possibility is especially interesting given previous work suggesting that holistic processing is a result of automatic and obligatory attention to all object parts (e.g., Richler, Wong, & Gauthier, 2011). Disruption of the perceptual grouping of face parts may facilitate an observer’s ability to selectively process the task-relevant part in the composite-face task, reducing indices of holistic face perception. This hypothesis is explored in the following three experiments.

Experiment 1

If disruption of perceptual grouping contributes to reduced holistic processing with misalignment, contextual manipulations that impact perceptual grouping should disrupt holistic face processing even in the absence of a disruption to the face configuration. Furthermore, if such an effect involves specialized face-processing mechanisms, these manipulations should primarily disrupt the processing of face, but not of nonface, stimuli. Here we modified the classic composite-face paradigm so as to disrupt the grouping of the face halves while leaving the configuration (alignment) of the facial features intact. This was done by manipulating the backgrounds behind the top and bottom face halves so that they appeared either to be two different fragments or part of a uniform field. In the former case, the two backgrounds were themselves misaligned (disrupting the gestalt cue of continuity) and were of different colors (disrupting the gestalt cue of similarity); in the latter case, they were aligned and of the same color. Notably, both discontinuities in contours and different coloration of the parts within objects have been demonstrated to disrupt the perception of an object as a single unit (Goldfarb & Treisman, 2011; Watson & Kramer, 1999). Importantly, the face halves themselves were always aligned with each other. The same manipulation was also applied to pictures from a nonface category—namely, cars.

Method

Participants

A group of 60 undergraduate students from Temple University participated in this study for course credit. The data from ten participants were excluded from the analyses for the reasons described in the Procedure section (final sample: 22 males, 28 females; age, M = 20.5 years, SD = 3.17). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided informed consent prior to participation.

Stimuli

The stimuli were 20 grayscale front-view images of faces with neutral expressions, cropped to remove the hair and ears, and 20 grayscale, profile-view car images (sedans). Two stimulus versions of each object were created, one centered on a blue background and the other centered on a red background. Additional copies of the images were made in which the background, but not the face/car, was shifted to the left or the right (see Fig. 1 for sample stimuli). All of the images were then divided along the horizontal plane at the bridge of the nose (for faces) or just above the wheel cavity (for cars).

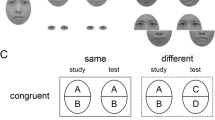

Procedure

Participants performed a part (top or bottom) matching task with chimeric images made from the tops and bottoms of different stimuli. Depending on which of two conditions the participants were randomly assigned to, they made such judgments about either face or car stimuli. The two image parts were separated by a black line six pixels wide. Each trial proceeded as follows: fixation screen (1,000 ms), a chimeric stimulus (1,000 ms), a pattern mask (2,000 ms), and a second chimeric stimulus (2,500 ms or until response). In “grouped” trials, the backgrounds of the top and bottom images were aligned and their colors matched. In “ungrouped” trials, the backgrounds of the top and bottom images were misaligned and of different colors (see Fig. 2). A cue, in the form of a horizontal bracket, appeared above or below the second chimeric image to indicate which of the two halves, top or bottom, the participants should judge to be the “same” or “different” in the two chimeric images. On half of the trials, the relationship between the task-irrelevant parts was congruent with that of the task-relevant parts, and on the other half the relationships were incongruent. For example, on a “congruent” bottom-matching trial, if the bottom parts of the two chimeric images were the same, the top parts would also match. In an “incongruent” trial, if the bottoms of the two images matched, the tops would differ (and vice versa). To the degree that participants were able to base their judgments on only the task-relevant part, without interference from the task-irrelevant part, there should be no effect of congruency. In previous studies, the difference in performance between congruent and incongruent trials has been greater for upright faces than for either inverted faces or nonface objects (Curby, Johnson, & Tyson, 2012; Gauthier, Curran, Curby, & Collins, 2003; Richler, Tanaka, Brown, & Gauthier, 2008). Notably, the degree to which the congruency effect was modulated by the physical misalignment of the face parts (i.e., the interaction between the effect of congruency and part misalignment) has also separated the performance between face and nonface (or inverted face) conditions in this task and is an established index of holistic processing (e.g., Richler, Cheung, et al. 2011). Trials in our study were blocked by background types (aligned/same color vs. misaligned/different colors), and four blocks of 32 trials were performed for each background type in a random order. Participants were given a practice session consisting of 16 trials to ensure that they were familiar with the task format. Trials in which a participant failed to input a response were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, the data from four participants who failed to respond to at least 85 % of the trials were excluded (the remaining participants lost an average of < 3 % of trials). In addition, the data from six participants were excluded due to poor performance (i.e., d′ ≤ 0 in at least one condition).

Trial structure used in Experiment 1, with examples from trials in which the context (left) encouraged or (right) discouraged the perceptual grouping of the face parts (referred to as the grouped and ungrouped conditions, respectively). The dashed bracket served as the cue in each trial to indicate which part (top or bottom) the participant should make the matching judgment on

Results and discussion

Sensitivity (d′) analysis

A 2 (grouping cues: grouped, ungrouped) × 2 (congruency: congruent, incongruent) × 2 (stimulus category: faces, cars) analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed on the sensitivity (d′) measures for each condition revealed main effects of congruency, F(1, 48) = 83.31, p ≤ .0001, and grouping cues, F(1, 48) = 4.60, p = .037, but not of stimulus category, F(1, 48) = 1.75, p = .19, with performance sensitivity for part matching being greater for congruent than for incongruent trials and for grouped than for ungrouped trials. We found a significant interaction between congruency and stimulus category, F(1, 48) = 15.21, p = .0003, with greater sensitivity for faces relative to cars in the congruent (p < .0001), but not in the incongruent, condition (p = .28). There was also a three-way interaction between congruency, stimulus category, and grouping cues, F(1, 48) = 4.12, p = .048. To unpack this interaction, separate two-way ANOVAs were performed on the data from the face and car conditions. For the face condition, significant main effects of grouping cues, F(1, 21) = 4.28, p = .05, and congruency, F(1, 21) = 57.95, p ≤ .0001, emerged, as well as an interaction between these variables, F(1, 21) = 7.02, p = .015, with greater sensitivity for the grouped than for the ungrouped faces in the congruent (p = .002), but not in the incongruent, condition (p = .77). In contrast, for the car condition, we found a main effect of congruency, F(1, 27) = 20.41, p = .0001, with greater sensitivity in the congruent than in the incongruent condition, but no main effect of, or interaction with, perceptual grouping cues (both ps > .35). Thus, as is shown in Fig. 3a, grouping cues modulated the congruency effect for faces but not for cars.Footnote 1

Sensitivity (d′) for the congruent (diamonds) and incongruent (squares) conditions, and the resulting index of holistic processing (filled bars, reflecting the difference between these conditions) for (a) upright faces and cars in Experiment 1 and (b) inverted faces in Experiment 2. Holistic processing was reduced (i.e., the congruency effect) for upright and inverted faces, but not for cars, when the stimuli were presented in the context of perceptual cues discouraging the grouping of the top and bottom parts. Error bars represent standard error values

Response time analysis

A similar ANOVA performed on the response times from correct trials revealed main effects of category, F(1, 48) = 10.44, p < .0022, and congruency, F(1, 48) = 13.65, p < .0006, with faster response times for face than for car trials and for congruent than for incongruent trials, but no effect of grouping cues, p = .93. No significant interactions emerged between any variables (all ps > .16). Thus, a trade-off between response time and d′ was not present, and thus cannot account for the effects present in the d′ data.

The greater effect of perceptual grouping cues on the congruency effect for faces, as compared to that for cars, is consistent with the hypothesis that disrupting the perceptual grouping of face parts contributes to the effect of misalignment on specialized holistic face-processing mechanisms. Notably, the difference in the impacts of the grouping cue manipulation on the face and car conditions cannot be attributed to an overall difference in performance levels between the two conditionsFootnote 2. However, it remains possible that stimulus-level differences between the face and car stimuli, such as their perceptual complexity or inherent part structure, may have contributed to the greater vulnerability of face processing to the contextual-grouping cue manipulation.

Experiment 2

To address the possibility that the results of Experiment 1 stemmed from stimulus-level differences between the face and car stimuli unrelated to holistic processing, in Experiment 2 we examined the effect of contextual-grouping cues on the holistic processing of inverted faces. Inverted faces have the same lower-level stimulus properties as upright faces but are processed less holistically. Thus, if the contextual-grouping cues that discourage the grouping of face parts impact on orientation-sensitive face-specific mechanisms, this effect should be attenuated for inverted faces. Specifically, in Experiment 2 we tested the interaction between grouping cues and congruency for inverted faces and, in a three-way ANOVA, compared this to the same interaction found for upright faces in Experiment 1.

Method

Participants and stimuli

A group of 36 individuals participated in this study for course credit. The data from six participants were excluded after applying the same exclusion criteria used in Experiment 1 (final sample: 30; 17 female, 13 male; age, M = 19.8 years, SD = 1.71Footnote 3). All of the participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided informed consent. The stimuli were the same face images used in Experiment 1, except that they were rotated (in-plane) 180°.

Procedure and data analysis

The procedure and data analysis were the same as in Experiment 1.

Results and discussion

Sensitivity (d′) analysis

A 2 (grouping cues: grouped, ungrouped) × 2 (congruency: congruent, incongruent) ANOVA performed on the sensitivity (d′) measures calculated for each condition revealed a main effect of congruency, F(1, 29) = 27.12, p ≤ .0001, with better performance sensitivity for part matching on congruent than on incongruent trials. No main effect emerged of grouping cues, p = .86. However, we did find an interaction between grouping cues and congruency, F(1, 29) = 6.11, p = .02, with the effect of congruency being greater in the grouped than in the ungrouped condition. Thus, the grouping cues significantly modulated holistic processing of the inverted faces.

A 2 (grouping cues: grouped, ungrouped) × 2 (congruency: congruent, incongruent) × 2 (orientation: upright, inverted) ANOVA comparing performance sensitivity with inverted faces to that with the upright faces from Experiment 1 revealed main effects of congruency, F(1, 50) = 91.50, p ≤ .0001, with greater sensitivity for congruent than for incongruent trials, and of orientation, F(1, 50) = 5.43, p = .024, with greater sensitivity for upright than for inverted faces. The main effect of grouping cues also approached significance, F(1, 50) = 3.10, p = .084, with somewhat greater sensitivity for grouped than for ungrouped trials. Congruency interacted with both orientation, F(1, 50) = 12.36, p = .0009, and grouping cues, F(1, 50) = 12.63, p = .0008, with greater sensitivity for upright than for inverted faces in the congruent (p < .0001), but not in the incongruent (p = .99), condition. The three-way interaction between congruency, orientation, and grouping cues was not significant (p = .86), as is shown in Fig. 3b, with grouping cues failing to disrupt the congruency effect more for upright than for inverted faces.Footnote 4

Response time analysis

A similar ANOVA performed on response times revealed a main effect of congruency, F(1, 50) = 43.5, p < .007, with faster response times for congruent than for incongruent trials. No main effect of orientation or grouping cues was present (both ps > .6). We also found no interactions between any variables (all ps > .19).

The similar impacts of the grouping cues manipulation on holistic processing, as indexed by the congruency effect, for upright and inverted faces appears inconsistent with a contribution of the perceptual grouping cues to the typically orientation-specific holistic perception of faces. However, some evidence has suggested that the difference between the processing of upright and inverted faces may be quantitative rather than qualitative, with inverted faces being processed in a manner qualitatively similar to that for upright faces, but less efficient (Richler, Mack, et al., 2011; Sekuler, Gaspar, Gold, & Bennett, 2004; Willenbockel et al., 2010). Specifically, Richler, Mack, et al. demonstrated that inverted faces can be processed holistically if sufficient encoding time is allowed. This is relevant, as the encoding time used in Experiment 2 was within the time frame that allows for holistic processing of inverted faces.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 included the same upright and inverted faces as in Experiments 1 and 2, but with an encoding time that only allowed for holistic processing of the upright faces. We predicted that if grouping cues specifically impact holistic face perception, the reduction in encoding time should eliminate the effect of the perceptual grouping cues on performance for inverted faces, while leaving this effect intact for upright faces.

Method

Participants and stimuli

A group of 68 individuals participated in this study for course credit. The data from 12 participants were excluded after applying the same exclusion criteria used in Experiment 1 (final sample: 56; 40 female, 16 male; age, M = 20.09 years, SD = 1.69). The participants were randomly assigned to the upright and inverted face conditions. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided informed consent. The stimuli were the same face images used in Experiments 1 and 2.

Procedure and data analysis

The procedure and data analysis were the same as in Experiment 1, except the trial event timing was as follows: fixation screen (1,000 ms), chimeric stimulus (1,000 ms), pattern mask with part cue (1,000 ms), second chimeric stimulus with part cue (200 ms), and pattern mask with part cue (2,500 ms or until response).

Results and discussion

Sensitivity (d′) analysis

A 2 (grouping cues: grouped, ungrouped) × 2 (congruency: congruent, incongruent) × 2 (orientation: upright, inverted) ANOVA revealed main effects of congruency, F(1, 54) = 194.52, p ≤ .0001, with greater sensitivity for congruent than for incongruent trials, and orientation, F(1, 54) = 26.05, p ≤ .0001, with greater sensitivity for upright than for inverted faces. We found no main effect of grouping cues (p = .96). Congruency interacted with orientation, F(1, 54) = 73.47, p ≤ .0001, with greater sensitivity for upright than for inverted faces in the congruent (p < .0001), but not in the incongruent (p = .99), condition. The three-way interaction between congruency, orientation, and grouping cues was also significant, F(1, 54) = 5.70, p = .021. To unpack this three-way interaction, separate two-way ANOVAs were performed on data from the upright and inverted conditions. For the upright condition, a main effect emerged of congruency, F(1, 27) = 182.5, p ≤ .0001, but not of grouping cues (p = .46). However, there was an interaction between congruency and grouping cues, F(1, 27) = 7.99, p = .0088, with greater sensitivity for the grouped, relative to the ungrouped, faces in the congruent (p = .01), but not in the incongruent (p = .21), condition. In contrast, for the inverted condition, we found a main effect of congruency, F(1, 27) = 23.66, p ≤ .0001, with greater sensitivity in the congruent that in the incongruent condition, but no main effect of, or interaction with, perceptual grouping cues (both ps > .42). Thus, as is shown in Fig. 4, grouping cues modulated the congruency effect for upright, but not for inverted, faces.Footnote 5

Sensitivity (d′) for the congruent (diamonds) and incongruent (squares) conditions, and the resulting index of holistic processing (filled bars, reflecting the difference between these conditions) for upright and inverted faces in Experiment 3. Holistic processing was reduced (i.e., the congruency effect) for upright as compared to inverted faces when faces were presented in the context of perceptual cues discouraging the grouping of the top and bottom parts. Error bars represent standard error values

Response time analysis

A similar ANOVA performed on response times revealed main effects of orientation, F(1, 54) = 6.08, p = .017, and congruency, F(1, 54) = 13.7, p < .0005, with faster response times for upright than for inverted and for congruent than for incongruent trials. We also found an interaction between orientation and congruency, F(1, 54) = 13.6, p = .0005, with a significant effect of congruency for upright (p < .0001), but not for inverted (p = .99), faces. However, there was no main effect of, or interaction with, grouping cues (ps > .12).

The impact of perceptual grouping cues on sensitivity (d′) for part judgments of upright, but not of inverted, faces when the presentation time was only sufficient to allow for holistic perception of upright faces is consistent with this effect influencing the specialized orientation-specific mechanisms supporting holistic face perception.

General discussion

Holistic processing, as measured in the composite-face paradigm, was disrupted by contextual cues that discouraged the perceptual grouping of the face parts (Exp. 1). Of note is the ability of such cues to impact holistic face perception even when the face parts themselves are aligned, and thus the configuration of the facial features is intact. In addition, the face-specific nature of this effect provided further support for the impact of perceptual grouping cues on specialized face-processing mechanisms.

Furthermore, the orientation-sensitive nature of this effect at short (200 ms), but not at long (2,500 ms), encoding durations is also consistent with an impact of perceptual grouping cues on holistic face perception (Exps. 2 and 3). Specifically, when the encoding duration was sufficient to allow for upright and inverted faces to be processed holistically (Richler, Mack, et al., 2011), we found an effect of the perceptual grouping manipulation on performance for both inverted and upright faces (Exp. 2). However, when the encoding time was reduced so as to no longer allow inverted faces to be processed holistically, contextual grouping cues only impacted upright face performance (Exp. 3). Notably, the impact of perceptual grouping cues on holistic processing of upright faces for both long (2,500 ms) and short (200 ms) encoding durations is consistent with previous reports that holistic processing can occur with as little as 183 ms presentations of upright faces (Richler, Mack, et al., 2011). This ability to predict and manipulate whether inverted and/or upright face perception would be impacted by our perceptual grouping manipulation, using knowledge of the distinct time courses of holistic processing for these stimuli (as previously documented by Richler, Mack, et al., 2011), provides strong evidence against a role of more general stimulus-based differences, unrelated to holistic processing, in driving these effects. Thus, the orientation sensitivity and temporal properties of the effect of perceptual grouping cues on face perception is consistent with the ability of such cues to impact specialized holistic-processing mechanisms.

The effect of perceptual grouping cues on holistic face processing, as indexed via the composite-face effect, offers insight into our understanding of the effect of misalignment on holistic face perception. A number of influential theories of face perception have proposed the existence of a face “norm” or “template” and that stimuli matching this general template trigger specialized face-processing mechanisms (e.g., Leopold, O’Toole, Vetter, & Blanz, 2001; Rhodes, Brennan, & Carey, 1987; Valentine, 1991). In the context of such theories, changing the configuration of the features within a face by misaligning the top and bottom halves presumably impacts holistic processing because the resulting stimulus no longer matches an internal face template. Thus, such stimuli would no longer trigger specialized (holistic) face perception mechanisms. However, the fact that the prototypical face configuration remained intact in our perceptual grouping manipulation suggests that misalignment may disrupt holistic processing not only by impacting the physical match of the face to an internal template, but also by breaking the perceptual grouping of the parts. This finding is not necessarily inconsistent with the existence of an internal face template (but see Richler, Mack, et al., 2011; Richler et al., 2008), but it does suggest that the perceived grouping of the facial features, not just their physical configuration, can interfere with the matching of a stimulus to an internal face template.

Recent work by Taubert and colleagues has suggested that both a template-matching process and a holistic-grouping process contribute to face processing, but on different time scales (Taubert & Alais, 2011; Taubert, Apthorp, Aagten-Murphy, & Alais, 2011). Specifically, the holistic process was suggested to occur before the template-matching process. Notably, abundant evidence has suggested that perceptual grouping mechanisms, such as those impacted by the contextual manipulation used in the experiments reported here, operate very early on in processing (Kimchi & Hadad, 2002). Thus, the potential of multiple distinct mechanisms to contribute to the unique hallmarks of face processing—that is, an earlier holistic-grouping mechanism and a later template-matching process—allows for the integration of the findings reported here with template-matching models of face perception.

Cues discouraging the grouping of face parts might disrupt holistic face perception via their impact on object-based attention. Object-based attention refers to when attentional deployment is guided by object structure rather than only by spatial location, as in the case of spatial attention (e.g., Egly, Driver, & Rafal, 1994). Perceptual grouping cues, via their contribution to the perception of objecthood, play an important role in defining the entities available for (object-based) attention selection. Specifically, indices of object-based attention are influenced by gestalt grouping principles like those manipulated in the present study (Kramer & Jacobson, 1991; Marino & Scholl, 2005; Matsukura & Vecera, 2006). Object-based attention is frequently indexed as facilitated allocation of attention to regions perceived as being part of the same object as a target (Kramer & Jacobson, 1991) or as a pretarget cue (Egly et al., 1994). This has been interpreted as reflecting an automatic spreading (Richard, Lee, & Vecera, 2008; Vecera & Farah, 1994) or prioritization (Shomstein & Yantis, 2002) of attention to regions within an attended object. Furthermore, depending on the task, this spread of attention through an object can facilitate or impair performance, depending on whether the information within regions of the same object is congruent or incongruent with the correct response to task-relevant information (e.g., Kramer & Jacobson, 1991).

One possibility is that holistic face perception, as indexed via the composite-face effect, stems in part from an automatic prioritization of both the task-relevant and -irrelevant face parts, due to the allocation of attention to the face as a unit—that is, object-based attention. Physically misaligning the face parts, thus disrupting the cohesiveness of the face as a unit of selection, might allow attention to more effectively target the task-relevant part. Consistent with this possibility, other manipulations known to disrupt objecthood and thus object-based attention, such as spatially separating different parts of an object or presenting them on different depth planes, has also been shown to disrupt holistic face perception (Taubert & Alais, 2009).

Furthermore, the tasks used to demonstrate object-based attention and those, such as the composite-face effect, used to index holistic face perception bear some striking similarities (Kramer & Jacobson, 1991; Richard et al., 2008). For example, Kramer and Jacobson had participants make a judgment about a target while ignoring adjacent distractors. The distractors, which served as targets on other trials, could be compatible or incompatible with respect to the correct response of the target. The key manipulation was that the distractors and the target could be embedded in the same object or in different objects. Kramer and Jacobson found a robust decrease in the compatibility effect when the target and distractors were embedded in different objects. In addition, this effect was modulated by perceptual cues encouraging (common color) or discouraging (different colors) the grouping of the target and flanking stimuli. In a similar vein, in the composite-face task used to index holistic processing, participants are asked to make a judgment about a target (top or bottom face part), while ignoring an adjacent distractor (the other, task-irrelevant part of the face). The task-irrelevant distractor parts also serve as targets on other trials and could be compatible or incompatible with respect to the correct response for the task-relevant target part. Furthermore, in a key manipulation in the composite task, the distractor is either aligned, thus binding with the target to make a coherent object, or misaligned, thus disrupting object-based attention. In this way, perceptual cues discouraging the grouping of face parts may serve to similarly disrupt the employment of object-based attention, facilitating participants’ ability to selectively attend to the task-relevant face part, resulting in a decrease in indices of holistic processing.

Given the orientation-specific nature of the impact of perceptual grouping cues on holistic face processing, it is notable that experience with a particular stimulus orientation can strengthen the perception of objecthood (Vecera & Farah, 1997). Experience has been identified as a key factor in image segmentation—that is, in determining whether and how perceptual features will be grouped. For example, fragments from upright letters are more strongly grouped than those from inverted letters or nonfamiliar shapes (Vecera & Farah, 1997). Specifically, participants are faster at determining whether two probed locations are on the same or different overlapping shapes when the shapes are upright letters, as compared to inverted letters or nonletter shapes. In addition, participants are faster to make a judgment about two features on separate fragments behind an occluding shape when their experience is consistent with these two features belonging to the same object versus different objects (Zemel, Mozer, Behrmann, & Bavelier, 2002). Evidence that experience- and stimulus-based influences on perceptual grouping occur in approximately the same time frame further supports the potential of experience to have a pervasive influence on the perception of objecthood, and thus on object-based attention (Kimchi & Hadad, 2002). Future studies should further probe the potential role of object-based attention in supporting holistic processing of faces, especially given other recent work also questioning the assumptions underlying traditional accounts of holistic face perception (Gold, Mundy, & Tjan, 2012).

In conclusion, holistic face perception, as indexed via the composite-face effect, is disrupted by cues discouraging the perceptual grouping of face parts. Given the key role that perceptual grouping cues play in determining the units of object-based attention, these findings suggest that object-based attention may contribute to the difficulty that observers experience when trying to selectively attend to parts within faces, which is characteristic of holistic face perception in the composite-face task. Future studies will be needed to determine the nature of the contribution of perceptual grouping to markers of holistic processing more generally.

Notes

An alternative index of holistic processing compares the hit rate for incongruent trials (see, e.g., Susilo et al., 2009). To aid in comparisons with the full existing literature, an ANOVA was performed on this subset of data. We found no main effects of, or interaction between, stimulus category and grouping cues, ps > .11. The results of this analysis should be interpreted cautiously, for two reasons: (1) the loss of power due to performing an analysis using only 25 % of our available data (i.e., only the hit rate) and (2) potential concerns that previous findings have suggested with this alternative method of analyzing the data (e.g., Cheung, Richler, Palmeri, & Gauthier, 2008; Richler, Cheung, et al., 2011; Richler, Mack, Palmeri, & Gauthier, 2011).

The pattern of significant findings remained the same after the mean sensitivities (d's) were matched across the face and car conditions (by removing the poorest performers in the car condition, the car group mean d' became 1.41, N = 22, as compared to the face group mean d' of 1.40, N = 22; p = .95).

Sex and age information was not collected from one participant.

A similar ANOVA performed on the hit rates for incongruent trials revealed a main effect of orientation, F(1, 50) = 9.29, p < .005, with higher hits rates for upright than for inverted trials. In addition, a main effect of grouping cues emerged, F(1, 50) = 6.98, p = .011, with higher performance in the grouped than in the ungrouped context. We found no interaction between orientation and grouping cue (F < 1). Again, the inconsistency between the results of this analysis and the analysis of d' likely reflects the unfortunate loss of power due to performing an analysis using only 25 % of our available data (i.e., only hit rates).

A similar ANOVA performed on the hit rates for incongruent trials revealed a main effect of orientation, F(1, 54) = 9.12, p < .005, with lower hit rates for upright than for inverted trials, but no main effect of grouping cues, F(1, 54) = 2.81, p = .10. In addition, the interaction between orientation and grouping cue was marginally significant, F(1, 54) = 3.78, p = .057, with better part judgments in the ungrouped than in the grouped context for upright (p = .01), but not for inverted (p = .85), faces. Notably, despite only utilizing 25 % of the available data, this pattern mimics that of the d' analysis utilizing the full data set.

References

Cheung, O. S., Richler, J. J., Palmeri, T. J., & Gauthier, I. (2008). Revisiting the role of spatial frequencies in the holistic processing of faces. Journal of Experimental Psycholology: Human Perception and Performance, 34, 1327–1336.

Curby, K. M., Johnson, K. J., & Tyson, A. (2012). Face to face with emotion: Holistic face processing is modulated by emotional state. Cognition and Emotion, 26, 93–102.

Egly, R., Driver, J., & Rafal, R. D. (1994). Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: Evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 123, 161–177. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.123.2.161

Gauthier, I., Curran, T., Curby, K. M., & Collins, D. (2003). Perceptual interference supports a non-modular account of face processing. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 428–432.

Gold, J. M., Mundy, P. J., & Tjan, B. S. (2012). The perception of a face is no more than the sum of its parts. Psychological Science, 23, 427–434.

Goldfarb, L., & Treisman, A. (2011). Does a color difference between parts impair the perception of a whole? A similarity between simultanagnosia patients and healthy observers. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 877–882.

Kimchi, R., & Hadad, B.-S. (2002). Influence of past experience on perceptual grouping. Psychological Science, 13, 41–47.

Kramer, A. F., & Jacobson, A. (1991). Perceptual organization and focused attention: The role of objects and proximity in visual processing. Perception & Psychophysics, 50, 267–284. doi:10.3758/BF03206750

Leopold, D. A., O’Toole, A. J., Vetter, T., & Blanz, V. (2001). Prototype-referenced shape encoding revealed by high-level aftereffects. Nature Neuroscience, 4, 89–94. doi:10.1038/82947

Marino, A. C., & Scholl, B. J. (2005). The role of closure in defining the “objects” of object-based attention. Perception & Psychophysics, 67, 1140–1149. doi:10.3758/BF03193547

Matsukura, M., & Vecera, S. P. (2006). The return of object-based attention: Selection of multiple-region objects. Perception & Psychophysics, 68, 1163–1175.

Rhodes, G., Brennan, S., & Carey, S. (1987). Identification and ratings of caricatures: Implications for mental representations of faces. Cognitive Psychology, 19, 473–497.

Richard, A. M., Lee, H., & Vecera, S. P. (2008). Attentional spreading in object-based attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 34, 842–853. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.34.4.842

Richler, J. J., Cheung, O. S., & Gauthier, I. (2011). Holistic processing predicts face recognition. Psychological Science, 22, 464–471.

Richler, J. J., Mack, M. L., Palmeri, T. J., & Gauthier, I. (2011). Inverted faces are (eventually) processed holistically. Vision Research, 51, 333–342.

Richler, J. J., Tanaka, J. W., Brown, D. D., & Gauthier, I. (2008). Why does selective attention to parts fail in face processing? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34, 1356–1368.

Richler, J. J., Wong, Y. K., & Gauthier, I. (2011). Perceptual expertise as a shift from strategic interference to automatic holistic processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 129–134. doi:10.1177/0963721411402472

Schiltz, C., Dricot, L., Goebel, R., & Rossion, B. (2010). Holistic perception of individual faces in the right middle fusiform gyrus as evidenced by the composite face illusion. Journal of Vision, 10(2), 25. 21–16.

Sekuler, A. B., Gaspar, C. M., Gold, J. M., & Bennett, P. J. (2004). Inversion leads to quantitative, not qualitative, changes in face processing. Current Biology, 14, 391–396.

Shomstein, S., & Yantis, S. (2002). Object-based attention: Sensory modulation or priority setting? Perception & Psychophysics, 64, 41–51. doi:10.3758/BF03194556

Susilo, T., Crookes, K., McKone, E., & Turner, H. (2009). The composite task reveals stronger holistic processing in children than adults for child faces. PLoS One, 4, e6460.

Taubert, J., & Alais, D. (2009). The composite illusion requires composite face stimuli to be biologically plausible. Vision Research, 49, 1877–1885.

Taubert, J., & Alais, D. (2011). Identity aftereffects, but not composite effects, are contingent on contrast polarity. Perception, 40, 422–436.

Taubert, J., Apthorp, D., Aagten-Murphy, D., & Alais, D. (2011). The role of holistic processing in face perception: Evidence from the face inversion effect. Vision Research, 51, 1273–1278.

Valentine, T. (1991). A unified account of the effects of distinctiveness, inversion, and race in face recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 43A, 161–204.

Vecera, S. P., & Farah, M. J. (1994). Does visual attention select objects or locations? Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 123, 146–160. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.123.2.146

Vecera, S. P., & Farah, M. J. (1997). Is visual image segmentation a bottom-up or an interactive process? Perception & Psychophysics, 59, 1280–1296. doi:10.3758/BF03214214

Watson, S. E., & Kramer, A. F. (1999). Object-based visual selective attention and perceptual organization. Perception & Psychophysics, 61, 31–49. doi:10.3758/BF03211947

Willenbockel, V., Fiset, D., Chauvin, A., Blais, C., Arguin, M., Tanaka, J. W., . . . Gosselin, F. (2010). Does face inversion change spatial frequency tuning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 122–135.

Young, A. W., Hellawell, D., & Hay, D. (1987). Configural information in face perception. Perception, 10, 747–759.

Zemel, R. S., Mozer, M. C., Behrmann, M., & Bavelier, D. (2002). Experience-dependent perceptual grouping and object-based attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 28, 202–217.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Curby, K.M., Goldstein, R.R. & Blacker, K. Disrupting perceptual grouping of face parts impairs holistic face processing. Atten Percept Psychophys 75, 83–91 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-012-0386-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-012-0386-9