Abstract

It is a common belief that smiling makes people appear younger. Empirical findings, however, suggest that smiling faces are actually perceived as older than neutral faces. Here we show that these two apparently contradictory phenomena can co-exist in the same person. In the first experiment, participants were first asked to estimate the ages of a series of smiling or neutral faces. After that, they were asked to estimate the average age of the set of neutral and smiling faces they had just evaluated. Finally, they were asked what effect smiling has on one’s perceived age. In the experimental session, smiling faces were perceived as older than neutral faces. Nevertheless, after the experiment, consistent with their retrospective evaluations, participants recalled smiling faces as being younger than the neutral faces. Experiment 2 replicated and extended these results to a set of emotional expressions that also included surprised faces. Smiling faces were again perceived as older than neutral faces, which were in turn perceived as older than surprised faces. Again, retrospective evaluations were consistent with the belief that smiling makes people look younger. The findings show that this belief, well-rooted in popular media, is a complete misconception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Smiling is used as a common social token across many everyday interactions – and photos of smiling faces dominate advertising and profile pictures on social media. This undoubtedly reflects the association of smiling with many positive characteristics (Jones, Debruine, Little, Conway, & Feinberg, 2006). It is perhaps not surprising therefore that people associate smiling with youthfulness (Voelkle, Ebner, Lindenberger, & Riediger, 2012).

Recent findings from our lab, however, suggest otherwise: smiling faces were actually perceived as older, not younger, than the same faces with a neutral expression (Ganel, 2015). We proposed that the “aging” effect of smiling originates from people’s inability to ignore the wrinkles that form around the eyes during smiling. Still, the scarce literature on the effect of smiling on perceived age is inconsistent (Hass, Weston, & Lim, 2016; Voelkle et al., 2012), and this inconsistency may be due to the clear discrepancy between the actual effect of smiling on perceived age and the common belief that smiling makes one look younger. The current study was explicitly designed to see if this discrepancy between perception and belief can exist in the same individual.

In Experiment 1, we first asked participants to evaluate the age of a series of smiling or neutral faces. To avoid effects of irrelevant differences between smiling and neutral faces, photos of the same people with either a neutral or a smiling expression were presented. To minimize the chances that age evaluations would be biased due to repeated presentations of the same people expressing different emotions, facial identity was counterbalanced across participants so that each participant was presented with a single (smiling or neutral) exemplar of each face (Ganel, 2015). In a second part of the experiment, which participants were not expecting, they were asked to rate the average age of the neutral and the smiling faces they had just evaluated. They were then asked a more general question about the effect of smiling on perceived age.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Forty Ben Gurion University of the Negev students (23 females, mean age: 24.23 years) participated in the experiment. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and received $7.00 or course credit for their participation. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Experimental design and procedure

The design and procedure of the first part of the experiment were similar to those used in a previous study (Ganel, 2015, Experiment 1a). Photos of 35 women and 35 men (average age: 25 years), each with neutral and smiling expressions, were taken from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) database (Lundqvist, Flykt, & Öhman, 1998). The photos were cropped to 7 × 9 cm and were presented on a 19-in. monitor using OpenSesame software. The 140 photos were divided into two equal sets: in Set A, a particular individual was smiling, while in Set B, he or she had a neutral expression (or vice versa). Half the participants were presented with smiling faces from Set A and neutral faces from Set B. The other participants were presented with the reverse. In each case, the faces from Sets A and B were presented in a random intermixed fashion. Participants were asked to evaluate the age of each face as accurately as possible.

Following the experimental session, participants were presented with a series of unanticipated questions. They were told that they had just been presented with a series of smiling and neutral faces, and were asked to estimate the average age evaluations they had given. Participants were then asked to select a general statement about the effect of smiling on perceived age: (1) smiling has no effect on perceived age; (2) smiling makes people look younger; or (3) smiling makes people look older.

Results and discussion

Overall, the 70 individuals in the photos were rated as looking older in the direct evaluation part of the experiment than they were in retrospective reports, whether or not the individuals in the photos were smiling. A repeated measures ANOVA design with task (direct vs. retrospective age evaluations) and expression (smiling vs. neutral) revealed a main effect of task [F(1,39) = 23.13, p < .001, ηp 2 = 0.37]. In addition, the main effect of expression was not significant [F(1,39) = <1]. More importantly, a significant interaction revealed that smiling had different effects on the direct and retrospective evaluations of age [F(1,39) = 40.33, p < .001, ηp 2 = 0.51].

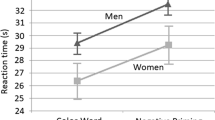

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the results of the direct evaluations of age closely replicate our previous findings (Ganel, 2015), namely that smiling faces were reliably rated as older than the same faces with a neutral expression [F(1,39) = 23.45, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.38]. More importantly, however, the retrospective reports of how old the people in the photos looked went in exactly the opposite direction: participants erroneously reported that they had perceived the smiling faces as younger than the neutral faces [F(1,39) = 14.76, p < .001, ηp 2 = 0.27]. This misconception was also reflected in the fact that 33 of the 40 participants thought that smiling makes people look younger, and six thought that smiling has no effect on perceived age. Only one of the 40 participants managed to capture the actual relationship between smiling and perceived age and thought that smiling makes people look older rather than younger.

Effects of smiling on average perceived age and on retrospective evaluations of age in Experiment 1. Smiling faces were perceived as older than neutral faces. At the same time, however, participants believed that they had evaluated the age of the smiling faces as younger than that of neutral faces. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (Jarmasz & Hollands, 2009)

The results of Experiment 1 show a clear dissociation between people’s perception of facial age and between their beliefs about the effect smiling has on perceived age. In a recent study, we showed in a series of experiments that smiling faces are perceived as older than neutral faces of the same people due to the formation of smile-associated wrinkles in the region of the eye (Ganel, 2015), which is considered as crucial for face perception (Namdar, Avidan, & Ganel, 2015; Rossion, 2009). Clearly, the results of Experiment 1 also show that people believe that smiling makes faces appear younger rather than older. This effect can probably be accounted for by the positive value associated with smiling across various social situations (Ganel, 2015; Jones et al., 2006; Otta, Lira, Delevati, Cesar, & Pires, 1994).

In Experiment 2 we aimed at replicating and extending the results of Experiment 1 within the context of a larger set of facial expressions. More particularly, in addition to neutral and smiling faces, we now asked participants to evaluate the perceived age of faces expressing a surprised emotion. Surprise is unique in that it involves a complete stretching of different sets of muscles around the region of the eyes (Ekman, Gowen, & Joseph, 1980). It is not surprising, therefore, that surprise leads to a decrease in the number and intensity of wrinkles around the region of the eyes, even compared to a neutral expression (for an illustration, see Fig. 2a). In agreement with the idea that age judgments are biased by the presence of wrinkles in the region of the eyes (Ganel, 2015), we predicted that surprise would therefore have an opposite effect on perceived age compared to smiling. Specifically, we predicted that unlike for smiling faces, surprised faces would be perceived as younger compared to neutral faces. In addition, unlike smiling, which is associated with positive attributes, surprise is not considered as either positive or negative (Meyer, Reisenzein, & Schützwohl, 1997). Based on the idea that the belief about the effect of emotion on perceived age is driven by commonly-held attributes associated with that particular emotion, we predicted that unlike smiling, which is associated with positive traits and would lead to biased retrospective evaluations of faces as being younger, surprise would not lead to a such a bias in retrospective age evaluation.

a Examples of stimuli used in Experiment 2. Note that unlike smiling, which increases the extent of wrinkles around the region of the eyes compared to a neutral expression, surprise has the opposite effect. b Effects of smiling and surprise on average perceived age and on retrospective evaluations of age in Experiment 2. Smiling faces were again perceived as older than neutral faces, but surprised faces were perceived as younger than neutral faces. As in Experiment 1, participants believed that they had evaluated the age of the smiling faces as younger than that of neutral faces. They did not believe that they had evaluated the surprised faces as appearing younger or older than the neutral faces. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (Jarmasz & Hollands, 2009)

Experiment 2

Method

Participants

Forty-two Ben Gurion University of the Negev students (32 females, mean age: 23.57 years) participated in the experiment. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and received $7.00 or course credit for their participation. One participant did not provide data for the retrospective age evaluation of neutral faces and her data were excluded from the associated analyses. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Experimental design and procedure

The design and procedure were similar in many aspects to those used in Experiment 1, with the exception that three expressions (smiling, neutral, surprise) rather than two expressions were used. Photos of 30 women and 30 men (average age: 25 years), with neutral, smiling, and surprised expressions were taken from the KDEF face database (Lundqvist, Flykt, & Öhman, 1998). The 180 photos were divided into three equal sets: in Set A, a particular individual was smiling, in Set B, he or she had a neutral expression, and in Set C, he or she had a surprised expression. Sets A, B, and C were counterbalanced between subjects in a similar manner to the counterbalancing method used in Experiment 1 (but now with six different counterbalancing orders), so that each participant saw the entire set of faces carrying the three emotions, but was presented with a single exemplar of each of the faces.

Following the experimental session, participants were presented with a series of unanticipated questions. They were told that they had just been presented with a series of smiling, surprised, and neutral faces, and were asked to estimate the average age evaluations they had given. Given the robust results on beliefs about the apparent age of smiling faces that were found in Experiment 1, a general statement questionnaire was not included in Experiment 2.

Results and discussion

A repeated measures ANOVA design with task (direct vs. retrospective age evaluations) and expression (smiling, neutral, and surprise) was conducted on the direct and on the retrospective age evaluations data. As can be seen in Fig. 2b, direct and retrospective age evaluations of smiling and neutral faces followed the same pattern of results reported in Experiment 1. Specifically, smiling faces were again perceived as older than neutral faces [F(1,40) = 25.06, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.39], but retrospective reports again went in the opposite direction, with smiling faces erroneously reported as being younger than neutral faces [F(1,40) = 26.09, p < .001, ηp 2 = 0.39]. In line with our prediction, direct age evaluations also showed that surprise, in contrast to smiling, led to facial age being evaluated as younger, not older, compared to a neutral expression [F(1,40) = 6.78, p < 0.05, ηp 2 = 0.14]. Moreover, retrospective evaluations of age did not differ between surprised and between neutral faces [F(1,40) < 1]. A main effect of task indicated that age was evaluated as overall older during direct age evaluations [F(1,40) = 29.78, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.43]. A significant interaction between task and expression indicated that the emotional expression of the face had different effects on perceived age and on retrospective evaluations of age [F(2,80) = 26.67, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.42].

The results of Experiment 2 replicate and extend the findings of Experiment 1 in several ways. First, the results provide a close replication of the pattern of the opposite effects that smiling has on direct ratings of age and on people’s common belief about the effect of smile on perceived age. Furthermore, the results emphasize the important role that wrinkles around the region of the eyes have on perceived age. Finally, the findings of the retrospective age evaluations show that common beliefs about age are driven by whether or not a particular emotion is associated with positive values. In the case of smiling, the relationship with positive values leads to the erroneous assumption that smiling faces are perceived as younger. In the case of surprise, which is not associated with positive or negative values, surprised faces are not considered to be perceived as either older or younger than neutral faces. Note that, as was the case for smiling, even for surprise there was a discrepancy between what people actually perceive and their retrospective assumptions. In other words, participants’ retrospective evaluations revealed that they were blind to the fact that they had rated surprised faces as appearing younger than neutral faces.

General discussion

The findings show, for the first time, that people can erroneously believe that smiling makes one appear younger, while at the same time rating smiling faces as older than neutral faces. Indeed, participants in our experiment were completely unaware that their perceptual performance defied their own beliefs.

The erroneous belief that smiling makes one appear younger could have potentially biased the results of relevant studies that did not consider the effects common beliefs have on overt age classifications. For example, Hass et al. (2016) asked participants to make general age classifications into two broad categories of “old” versus “young” for a series of computerized faces that did not include several realistic attributes, such as wrinkles. It is possible, therefore, that decisions in this study were influenced by semantic knowledge and by commonly-held beliefs about age, which could have biased the age classifications of smiling faces as being younger, not older, compared to neutral faces. In a similar vein, Voelkle and his colleagues (2012) did not report significant differences between the perceived age of smiling and neutral faces. In this study, an extensive set of faces across different ages and expressions was used, and participants were presented with many different exemplars of the same faces across different emotional expression. Multiple presentations of the same person with different expressions could have biased participants’ age evaluations by allowing their ratings to be driven by common beliefs about age rather than by direct ratings only. The results of the present study, which highlight a sharp discrepancy between the effect of smiling and surprise on the direct perception of age and common beliefs about their effect on the perception of age, call for a careful consideration of the experimental designs used to measure perceived age in face recognition studies.

The idea that smiling makes one look younger can be found throughout popular media and is widely promoted by skin and dental care companies that have a clear financial interest in emphasizing the positive effect of smiling on how youthful one appears. Here, we show that this belief, which is well-rooted in popular culture, is a complete misconception. Smiling faces are not perceived as younger than neutral faces; they are perceived as older. Moreover, our results make it clear that the same person can believe that smiling makes one appear younger, but at the same time judge smiling faces as older than neutral faces.

References

Ekman, P., Gowen, R., & Joseph, C. H. (1980). Deliberate facial movement. Child development, 886–891.

Ganel, T. (2015). Smiling makes you look older. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(6), 1671–1677. doi:10.3758/s13423-015-0822-7

Hass, N. C., Weston, T. D., & Lim, S. L. (2016). Be happy Not Sad for your youth: The effect of emotional expression on Age perception. PLoS One, 11(3), e0152093. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152093

Jarmasz, J., & Hollands, J. G. (2009). Confidence intervals in repeated-measures designs: The number of observations principle. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(2), 124–138. doi:10.1037/a0014164

Jones, B. C., Debruine, L. M., Little, A. C., Conway, C. A., & Feinberg, D. R. (2006). Integrating gaze direction and expression in preferences for attractive faces. Psychological Science, 17(7), 588–591. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01749.x

Lundqvist, D., Flykt, A., & Öhman, A. (1998). The karolinska directed emotional faces (KDEF). CD ROM from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section, Karolinska Institutet, 91–630.

Meyer, W.-U., Reisenzein, R., & Schützwohl, A. (1997). Toward a process analysis of emotions: The case of surprise. Motivation and Emotion, 21(3), 251–274.

Namdar, G., Avidan, G., & Ganel, T. (2015). Effects of configural processing on the perceptual spatial resolution for face features. Cortex, 72, 115–123. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.04.007

Otta, E., Lira, B. B., Delevati, N. M., Cesar, O. P., & Pires, C. S. (1994). The effect of smiling and of head tilting on person perception. Journal of Psychology, 128(3), 323–331. doi:10.1080/00223980.1994.9712736

Rossion, B. (2009). Distinguishing the cause and consequence of face inversion: The perceptual field hypothesis. Acta Psychologica, 132(3), 300–312. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2009.08.002

Voelkle, M. C., Ebner, N. C., Lindenberger, U., & Riediger, M. (2012). Let me guess how old you are: Effects of age, gender, and facial expression on perceptions of age. Psychology and Aging, 27(2), 265–277. doi:10.1037/a0025065

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ganel, T., Goodale, M.A. The effects of smiling on perceived age defy belief. Psychon Bull Rev 25, 612–616 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1306-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1306-8