Abstract

As concerns of “reform fatigue” in lower- and middle-income countries have become more widespread, so has the search for ways of boosting support for market-oriented reforms. Although the effects of political institutions on reform results have been extensively analyzed, there has been relatively little investigation of their effects on public opinion. We argue that constitutional and extra-constitutional reforms that place limits on the discretionary authority of public officials and enable voters to monitor, reward, and sanction politicians can enhance the legitimacy of market reforms. We present a voting model with asymmetric information to illustrate that these formal-legal reforms provide a credible signal of reformers’ commitments. Using panel data based on public opinion barometers from Eastern Europe and Latin America, we examine the effects of political authority on public support for markets. We find that constraints on the power of the executive branch boost support for markets but that this effect declines as the reform process matures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At the outset of the postcommunist transition, for example, group demands were generally not filtered through formal channels. Rather, smaller groups of firms—often single firms—were more likely to lobby the state directly for specific objectives (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1999).

This model applies not to economies that have yet to reform but to economies that have already initiated the reform process and to economies in which reform-oriented incumbents face anti-reform challenges. If an anti-reform politician were the incumbent, reform outcomes would simply be explained by the preferences of that politician because, by definition, reform would not be on the agenda of the incumbent government.

Benefits can take various forms, including reputational benefits for countries that improve political accountability. But there is also, of course, a personal cost to politicians for institutional reforms that allow closer scrutiny of governmental activities.

These outcomes correspond to three distinct points along the so-called J-curve of reform, a continuous representation of welfare as a function of reform progress. The status quo, from this perspective, represents an intermediate level of welfare, which is expected to deteriorate in the “valley of transition” before improving (see, for example, Przeworski, 1991).

This assumption merely simplifies the exposition; it is by no means necessary for the result.

Our core sample includes the following countries from each region: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela (in Latin America); Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and Ukraine (in Eastern Europe/CIS). The question regarding support for a market economy—the responses to which we use to construct our indicator of support for market reform—has only appeared in LB surveys since 1998. Consequently, time periods also differ across regional groups (1990 to 1997 for Eastern Europe/CIS, and 1998 to 2002 for Latin America). When pooling the samples, we compensate for these different period observations, as noted below, by including time dummies in our benchmark specifications. Note, finally, that surveys conducted in the former Czechoslovakia and U.S.S.R. were republic-specific, allowing us to compare responses before and after the breakups of these unions.

These questions are worded slightly differently between surveys. In the CEEB:

Do you personally feel that the creation of a free-market economy, that is, one free from state control, is right or wrong for our country’s future?

In the LB:

Do you somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree [with the following phrase]: a market economy is best for the country?

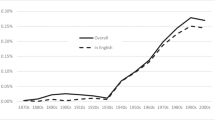

Note that this different wording creates some problems for comparison between the two regions. First, in the CEEB survey, the “future” is explicitly stated in the question, whereas in the LB survey it is not. Second, possible answers to the CEEB question are “right,” “wrong,” or “don’t know,” but in the LB survey there are three possible answers in addition to “don’t know.” Although there are no perfect corrections for these differences, we feel that the benefits from cross-regional comparison far outweigh the potential for misinterpretation. We try to make responses to these questions comparable by performing two corrections. First, rather than estimating solely the percentages that responded “agree” or “right,” we subtract the percentage that answered in the negative from the percentage that answered in the affirmative to determine the “net support” for market-based reforms. Second, when pooling responses, we always use country fixed effects as a robustness check to correct for any country- or region-specific effects that cannot be readily observed, including differences in the implementation of the surveys.

These and the subsequent estimated values are obtained holding all other variables at their means.

The polity ranges from −10 to +10. We rescale as (10 + polity)/20 to yield a score that ranges from 0 (least democratic) to 1 (most democratic).

References

Alesina, A., and A. Drazen, 1991, “Why Are Stabilizations Delayed?” American Economic Review, Vol. 81 (December), pp. 1170–88.

Anderson, C., 1995, Blaming the Government: Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe).

Åslund, A., 2000, “Why Has Ukraine Failed to Achieve Economic Growth?” in Economic Reform in Ukraine: The Unfinished Agenda, ed. by Åslund and G. de Ménil (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe).

—, P. Boone, and S. Johnson, 2001, “Escaping the Under-Reform Trap,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 48 (Special Issue), pp. 88–108.

Beck, N., 2001, “Time-Series-Cross-Section Data: What Have We Learned in the Past Few Years?” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 4, pp. 271–93.

Cabanero-Vervosa, C., and P. Mitchell, 2003, “Communicating Economic Reform” (unpublished; Washington: World Bank).

Camdessus, M., 1997, “Camdessus Calls for ‘Second Generation’ of Reform in Argentina,” IMF Survey, Vol. 26 (June 9), pp. 175–76.

Corrales, J., 2002, Presidents without Parties: The Politics of Economic Reform in Argentina and Venezuela in the 1990s (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press).

De Melo, M., C. Denizer, and A. Gelb, 1996, “Patterns of Transition from Plan to Market,” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 397–424.

Diaz-Cayeros, A., and B. Magaloni, 2003, “The Politics of Public Spending—Part II. The Programa Nacional de Solidaridad (PRONASOL) in Mexico,” background paper to the World Development Report 2004 (Washington: World Bank).

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), 1999, Transition Report 1999: Ten Years of Transition (London: EBRD).

Fearon, J. D., 1999, “Electoral Accountability and the Control of Politicians: Selecting Good Types versus Sanctioning Poor Performance,” in Democracy, Accountability, and Representation, Cambridge Studies in the Theory of Democracy No. 2, ed. by A. Przeworski, S. C. Stokes, and B. Manin (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Ferejohn, J., 1986, “Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control,” Public Choice, Vol. 50 (January), pp. 5–25.

Gonzalez, M., 2002, “Do Changes in Democracy Affect the Political Budget Cycle? Evidence from Mexico,” Review of Development Economics, Vol. 6 (June), pp. 204–24.

Harrington, J. E., Jr., 1993, “Economic Policy, Economic Performance, and Elections,” American Economic Review, Vol. 83 (March), pp. 27–42.

Hellman, J. S., 1998, “Winners Take All: The Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions,” World Politics, Vol. 50 (January), pp. 203–34.

Henisz, W. J., 2000, “The Institutional Environment for Economic Growth,” Economics and Politics, Vol. 12 (March), pp. 1–32.

Johnson, S., and others, 2000, “Tunneling,” American Economic Review, Vol. 90 (May), pp. 22–27.

Kim, B.-Y., and J. Pirttilä, 2003, “The Political Economy of Reforms: Empirical Evidence from Post-Communist Transition in the 1990s,” BOFIT Discussion Paper No. 4 (Helsinki: Institute for Economies in Transition, Bank of Finland).

Krueger, A. O., ed., 2000, Economic Policy Reform: The Second Stage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Kuczynski, P.-P., 2003, “Reforming the State,” in After the Washington Consensus: Restarting Growth and Reform in Latin America, ed. by Kuczynski and J. Williamson (Washington: Institute for International Economics).

Kurtz, M. J., 2004, “The Dilemmas of Democracy in the Open Economy: Lessons from Latin America,” World Politics, Vol. 56 (January), pp. 262–302.

Laban, R., and F. Sturzenegger, 1994, “Distributional Conflict, Financial Adaptation and Delayed Stabilizations,” Economics and Politics, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 257–76.

Lora, E., and M.Olivera, 2005, “The Electoral Consequences of the Washington Consensus,” Economía, Vol. 5 (Spring).

Lora, E., U. Panizza, and M. Quispe-Agnoli, 2004, “Reform Fatigue: Symptoms, Reasons, and Implications,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, Vol. 89 (Second Quarter), pp. 1–28.

Manin, B., 1997, The Principles of Representative Government (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Marshall, M. G., and K. Jaggers, 2001, Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions. Available via the Internet: http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/inscr/polity

Mejía Reyes, P., 2003, “Business Cycles and Economic Growth in Latin America: A Survey,” Documentos de Investigación No. 71 (Mexico City: Colegio Mexiquense).

Naím, M., 1994, “Latin America: The Second Stage of Reform,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 5 (October), pp. 32–48.

O’Donnell, G. A., 1994, “Delegative Democracy,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 5 (January), pp. 55–69.

Ortiz, G., 2003, “Latin America and the Washington Consensus: Overcoming Reform Fatigue,” Finance and Development, Vol. 40 (September), pp. 14–17.

Plattner, M. F., 1999, “From Liberalism to Liberal Democracy,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 10 (July), pp. 121–34.

Political Risk Services, 2005, International Country Risk Guide (East Syracuse, New York: The PRS Group, Inc.). Available via the Internet: http://www.countrydata.com

Przeworski, A., 1991, Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Rodrik, D., 1993, “Positive Economics of Policy Reform,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 83 (May), pp. 356–61.

Schady, N. R., 2000, “The Political Economy of Expenditures by the Peruvian Social Fund (FONCODES) 1991–95,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 94 (June), pp. 289–304.

Schuknecht, L., 2000, “Fiscal Policy Cycles and Public Expenditure in Developing Countries,” Public Choice, Vol. 102 (January), pp. 113–28.

Shleifer, A., and D. Treisman, 2000, Without a Map: Political Tactics and Economic Reform in Russia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press).

Stokes, S. C., 2001a, “Economic Reform and Public Opinion in Fujimori’s Peru,” in Public Support for Market Reforms in New Democracies, Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics, ed. by Stokes (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press).

—, 2001b, Mandates and Democracy: Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America (Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York: Cambridge University Press).

Tommasi, M., and A. Velasco, 1996, “Where Are We in the Political Economy of Reform?” Journal of Policy Reform, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 187–238.

Tsebelis, G., 2002, Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

Velasco, A., 1997, “A Model of Endogenous Fiscal Deficits and Delayed Fiscal Reforms,” NBER Working Paper No. 6336 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Warner, A. M., 2001, “Is Economic Reform Popular at the Polls? Russia 1995,” Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 29 (September), pp. 448–65.

Williamson, J., ed., 1994, The Political Economy of Policy Reform (Washington: Institute for International Economics).

World Bank, 2004a, World Development Report 2005: A Better Investment Climate for Everyone (New York: Oxford University Press).

—, 2004b, Unlocking the Employment Potential in the Middle East and North Africa: Toward a New Social Contract (Washington: World Bank).