Abstract

Background: A consensus regarding the components of a patient-centered approach to healthcare does not exist. Although patient-centered care should be predicated on patient preferences, existing models provide little evidence regarding the relative importance of different care processes to patients themselves.

Objective: To involve patients in the design of a model of patient-centered care for a corporation of Canadian teaching hospitals.

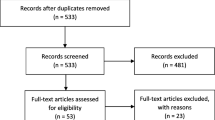

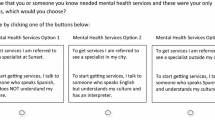

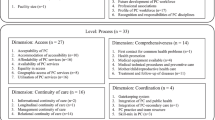

Methods: Using themes from focus groups and interviews, a conjoint survey was developed comprising 14 four-level patient-centered care attributes. Sawtooth Software’s Choice Based Conjoint module (version 2.6.7) was used to design the survey. Each participant completed 15 choice tasks, each task presenting a choice between three hospitals described by a different combination of patient-centered care attribute levels. Latent class analysis was used to identify segments of participants with similar patient-centered care choice patterns. Randomized First Choice simulations were used to predict the percentage of participants in each segment who would choose different approaches to improving patient-centered care.

Representative hospital service users were recruited from a corporation of five Canadian teaching hospitals serving a regional population of 2.2 million.

Results: A total of 508 patients and family members of children completed a choice-based conjoint survey. Latent class analysis revealed two segments: an informed care segment and a convenient care segment. Participants in the informed care segment (71.3% of the sample) were more likely to have higher education, be non-immigrants, speak English as a first language, and be outpatients or family members.

The information needed to understand health concerns, an opportunity to learn health improvement skills, teams that communicated effectively, short waiting times, and collaborative treatment planning were more important to the informed care segment than to the convenient care segment. Convenient settings, a welcoming environment, and ease of internal access exerted a greater influence on the choices made by the convenient care segment. Both segments preferred hospitals that provided health information and gave prompt feedback on patient progress.

Conclusions: This study suggests that many patients would exchange an increase in waiting times for prompt feedback, information, and the skills to improve their health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Briefly, Hierarchical Bayes estimates the vector of mean population betas, the matrix of population beta covariances, and the vector of betas for each respondent by drawing from two distributions: (i) a prior distribution drawn from a multivariate Normal distribution, and (ii) a posterior distribution based on a multinomial logit model derived from actual responses.[43] Using an iterative three-step (Gibbs sampling) process and Methopolis Hastings Algorithm,[46] the program re-estimates one set of parameters (α, D, or the betas) conditionally, given current values for the other two sets.[43] Using default estimates of beta and alpha, we computed 2000 burn-in iterations before convergence was assumed. We computed 12 000 iterations, accepting 1000 draws per respondent with a skip factor of 10 to increase the independence of draws and improve the precision of our estimates.

The IIA problem is a property of logit models that results in unrealistic share predictions when highly similar attribute options compete with very different attribute options. To stabilize our share of preference estimates, we computed 100 000 sampling iterations.

References

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001

Stewart M, Brown J, Weston W. Patient-centred medicine: transforming the clinical method. 2nd ed. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd, 2005

Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; (4): CD003267

Scott A, Vick S. Patients, doctors and contracts: an application of principal-agent theory to the doctor-patient relationship. Scott J Polit Econ 1999; 46(2): 111–34

Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med 1996 Oct 15; 125(8): 640–5

Ogden J, Ambrose L, Khadra A, et al. A questionnaire study of GPs’ and patients’ beliefs about the different components of patient centredness. Patient Educ Couns 2002 Jul; 47(3): 223–7

Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, et al. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med 2002 Apr; 17(4): 243–52

Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. The Diabetes Care From Diagnosis Research Team. BMJ 1998 Oct 31; 317(7167): 1202–8

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ 2001 Feb 24; 322(7284): 468–72

Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ 2002 Nov 30; 325(7375): 1263–5

Barbour RS. The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. J Health Serv Res Pol 1999 Jan; 4(1): 39–43

Bridges JF. Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: an emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Appl Health Econ Health Pol 2003; 2(4): 213–24

Coast J. The appropriate uses of qualitative methods in health economics. Health Econ 1999 Jun; 8(4): 345–53

Orme BK. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Madison (WI): Research Publishers, 2006

Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ 2000 Jun 3; 320(7248): 1530–3

Luce RD, Tukey JW. Simultaneous conjoint measurement: a new type of fundamental measurement. J Math Psychol 1964; 1(1): 1–27

Green PE, Srinivasan V. Conjoint analysis in consumer research: issues and outlook. J Consum Res 1978; 5(2): 103–23

Huber J. Predicting preferences on experimental bundles of attributes: a comparison of models. J Market Res 1975; 12(3): 290–7

Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F. Conjoint analysis as an instrument of market research practice. In: Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F, editors. Conjoint measurement. Berlin: Springer, 2007: 3–34

Bridges JFP, Onukwugha E, Johnson RF, et al. Patient preference methods: a patient centered evaluation paradigm. ISPOR Connections 2007 Dec; 13(6): 4–7

Phillips KA, Johnson FR, Maddala T. Measuring what people value: a comparison of ‘attitude’ and ‘preference’ surveys. Health Serv Res 2002 Dec; 37(6): 1659–79

Payne J, Bettman J, Johnson E. The adaptive decision maker. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press, 1993

Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001; 5(5): 1–186

Bridges JF. Future challenges for the economic evaluation of healthcare: patient preferences, risk attitudes and beyond. Pharmacoeconomics 2005; 23(4): 317–21

Morgan A, Shackley P, Pickin M, et al. Quantifying patient preferences for out-of-hours primary care. J Health Serv Res Policy 2000 Oct; 5(4): 214–8

Osman LM, McKenzie L, Cairns J, et al. Patient weighting of importance of asthma symptoms. Thorax 2001 Feb; 56(2): 138–42

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D. Patient willingness to take teriparatide. Patient Educ Couns 2007 Feb; 65(2): 237–44

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D. Patient treatment preferences for osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 2006 Oct 15; 55(5): 729–35

Fraenkel L, Constantinescu F, Oberto-Medina M, et al. Women’s preferences for prevention of bone loss. J Rheumatol 2005 Jun; 32(6): 1086–92

Stanek EJ, Oates MB, McGhan WF, et al. Preferences for treatment outcomes in patients with heart failure: symptoms versus survival. J Card Fail 2000 Sep; 6(3): 225–32

McGregor JC, Harris AD, Furuno JP, et al. Relative influence of antibiotic therapy attributes on physician choice in treating acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Med Decis Making 2007 Jul–Aug; 27(4): 387–94

Cunningham CE, Deal K, Neville A, et al. Modeling the problem-based learning preferences of McMaster University undergraduate medical students using a discrete choice conjoint experiment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2006 Aug; 11(3): 245–66

Jung HP, Baerveldt C, Olesen F, et al. Patient characteristics as predictors of primary health care preferences: a systematic literature analysis. Health Expect 2003 Jun; 6(2): 160–81

Scott A, Watson MS, Ross S. Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by general practitioners: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med 2003 Feb; 56(4): 803–14

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003; 2(1): 55–64

Sawtooth Software Inc. Sequim (WA) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com [Accessed 2008 Mar20]

Patterson M, Chrzan, K. Partial profile discrete choice: what’s the optimal number of attributes? 2003 Sawtooth Software Conference Proceedings. Sequim (WA): Sawtooth Software, 2004

Sawtooth Software Inc. The CBC latent class technical paper (version 3). Sequim (WA): Sawtooth Software Inc., 2004:1–20

Ali JS, McDermott S, Gravel RG. Recent research on immigrant health from statistics Canada’s population surveys. Can J Public Health 2004 May–Jun; 95(3): I9–13

Ramaswamy V, Cohen SH. Latent class models for conjoint analysis. In: Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F, editors. Conjoint measurement methods and applications. 4th ed. Heidelberg: Springer, 2007: 295–320

Desarbo WS, Ramaswamy V, Cohen SH. Market segmentation with choice-based conjoint analysis. Mark Lett 1995; 6(2): 137–47

Vriens M, Wedel M, Wilms T. Metric conjoint segmentation methods: a Monte Carlo comparison. J Market Res 1996; 33(1): 73–85

Sawtooth Software Inc. The CBC/HB system for hierarchical Bayes estimation: version 4.0 [technical paper]. Sequim (WA): Sawtooth Software Inc., 2004: 1–32

Allenby GM, Bakken DG, Rossi PE. The HB revolution: how Bayesian methods have changed the face of marketing research. Marketing Research 2004; 16(2): 20–5

Allenby GM, Fennell G, Huber J, et al. Adjusting choice models to better predict market behavior. Market Lett 2005 December; 16(3–4): 197–208

Chib S, Greenberg E. Understanding the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. Am Stat 1995 Nov; 49(4): 327–35

Huber J, Orme B, Miller R. Dealing with product similarity in conjoint simulations. In: Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F, editors. Conjoint measurement: methods and applications. 4th ed. New York: Springer, 2007: 347–62

Orme BK, Huber J. Improving the value of conjoint simulations. Marketing Research 2000; 12(4): 12–20

Orme BK, Baker GC. Comparing Hierarchical Bayes draws and randomized first choice for conjoint simulations [Sawtooth Software research paper series]. Sequim (WA): Sawtooth Software Inc., 2000 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/download/techpap/rfcdrw.pdf [Accessed 2008 Mar 20]

Gustafsson A, Herrmann A, Huber F. Conjoint measurement: methods and applications. 4th ed. Berlin: Springer, 2007

Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, et al. Primary care and health system performance: adults’ experiences in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 Jul–Dec; Suppl. web exclusives: W4-487-503

Beach MC, Roter DL, Wang NY, et al. Are physicians’ attitudes of respect accurately perceived by patients and associated with more positive communication behaviors? Patient Educ Couns 2006 Sep; 62(3): 347–54

Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, et al. Diabetes patient education: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Patient Educ Couns 2004 Jan; 52(1): 97–105

McPherson CJ, Higginson IJ, Hearn J. Effective methods of giving information in cancer: a systematic literature review of randomized controlled trials. J Public Health Med 2001 Sep; 23(3): 227–34

Janson SL, Fahy JV, Covington JK, et al. Effects of individual self-management education on clinical, biological, and adherence outcomes in asthma. Am J Med 2003 Dec 1; 115(8): 620–6

Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, et al. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002 Jul; 25(7): 1159–71

Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD, et al. Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): a multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2003 Dec 8–22; 163(22): 2775–83

DiClemente CC, Marinilli AS, Singh M, et al. The role of feedback in the process of health behavior change. Am J Health Behav 2001 May–Jun; 25(3): 217–27

Chapin RB, Williams DC, Adair RF. Diabetes control improved when inner-city patients received graphic feedback about glycosylated hemoglobin levels. J Gen Intern Med 2003 Feb; 18(2): 120–4

Cope GF, Nayyar P, Holder R. Feedback from a point-of-care test for nicotine intake to reduce smoking during pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem 2003 Nov; 40 (Pt 6): 674–9

Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ. Do tailored behavior change messages enhance the effectiveness of health risk appraisal? Results from a randomized trial. Health Educ Res 1996 Mar; 11(1): 97–105

McClure JB. Are biomarkers useful treatment aids for promoting health behavior change? An empirical review. Am J Prev Med 2002 Apr; 22(3): 200–7

Williams JG, Cheung WY, Chetwynd N, et al. Pragmatic randomised trial to evaluate the use of patient held records for the continuing care of patients with cancer. Qual Health Care 2001 Sep; 10(3): 159–65

Cimino JJ, Patel VL, Kushniruk AW. The patient clinical information system (PatCIS): technical solutions for and experience with giving patients access to their electronic medical records. Int J Med Inform 2002 Dec 18; 68(1–3): 113–27

Harrington J, Noble LM, Newman SP. Improving patients’ communication with doctors: a systematic review of intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns 2004 Jan; 52(1): 7–16

Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD. Patient information-seeking behaviors when communicating with doctors. Med Care 1990 Jan; 28(1): 19–28

Freeman GK, Horder JP, Howie JG, et al. Evolving general practice consultation in Britain: issues of length and context. BMJ 2002 Apr 13; 324(7342): 880–2

Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, et al. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: have we improved? JAMA 1999 Jan 20; 281(3): 283–7

Doupi P, van der Lei J. Design considerations for a personalised patient education system. Stud Health Technol Inform 2003; 95: 762–7

Clancy DE, Cope DW, Magruder KM, et al. Evaluating group visits in an uninsured or inadequately insured patient population with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2003 Mar–Apr; 29(2): 292–302

Houghton S, Saxon D. An evaluation of large group CBT psycho-education for anxiety disorders delivered in routine practice. Patient Educ Couns 2007 Sep; 68(1): 107–10

Rickheim PL, Weaver TW, Flader JL, et al. Assessment of group versus individual diabetes education: a randomized study. Diabetes Care 2002 Feb; 25(2): 269–74

Webster P. Canada’s new prime minister vows to cut surgery wait lists: Martin considers point-scoring systems to rationalise and speed scheduling. Lancet 2004 Jan 17; 363(9404): 216–7

Morey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTearns project. Health Serv Res 2002 Dec; 37(6): 1553–81

Risser DT, Rice MM, Salisbury ML, et al. The potential for improved teamwork to reduce medical errors in the emergency department. The MedTeams Research Consortium. Ann Emerg Med 1999 Sep; 34(3): 373–83

Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2000 Mar 18; 320(7237): 745–9

Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med 2004 Feb; 79(2): 186–94

Neale G, Woloshynowych M, Vincent C. Exploring the causes of adverse events in NHS hospital practice. J R Soc Med 2001 Jul; 94(7): 322–30

Campbell SM, Harm M, Hacker J, et al. Identifying predictors of high quality care in English general practice: observational study. BMJ 2001 Oct 6; 323(7316): 784–7

Spath PL. Error reduction in health care: systems approach to improving patient safety. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass, 2000

Joffe S, Manocchia M, Weeks JC, et al. What do patients value in their hospital care? An empirical perspective on autonomy centred bioethics. J Med Ethics 2003 Apr; 29(2): 103–8

Davis MA, Hoffman JR, Hsu J. Impact of patient acuity on preference for information and autonomy in decision making. Acad Emerg Med 1999 Aug; 6(8): 781–5

Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, et al. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995 Dec; 33(12): 1176–87

Arora N, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care 2000 Mar; 38(3): 335–41

Benbassat J, Pilpel D, Tidhar M. Patients’ preferences for participation in clinical decision making: a review of published surveys. Behav Med 1998 Summer; 24(2): 81–88

Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med 1996 Jul 8; 156(13): 1414–20

Wensing M, Vingerhoets E, Grol R. Feedback based on patient evaluations: a tool for quality improvement? Patient Educ Couns 2003 Oct; 51(2): 149–53

Entwistle VA, Andrew JE, Emslie MJ, et al. Public opinion on systems for feeding back views to the National Health Service. Qual Saf Health Care 2003 Dec; 12(6): 435–42

Loukanova S, Molnar R, Bridges JFP. Promoting patient empowerment in the healthcare system: highlighting the need for patient-centered drug policy. Exp Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2007; 7(3): 281–9

Roter D. The medical visit context of treatment decision-making and the therapeutic relationship. Health Expect 2000 Mar; 3(1): 17–25

Cunningham CE, Woodward CA, Shannon HS, et al. Readiness for organizational change: a longitudinal study of workplace, psychological and behavioural correlates. J Occup Organ Psychol 2002; 75(4): 377–92

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Jack Laidlaw Chair in Patient-Centered Health Care, a Contribution Agreement from CANARIE Inc., and the Institute for Knowledge Innovation and Technology (IKIT) at the University of Toronto. The authors acknowledge the support of the Hamilton Health Sciences’ Patient-Centered Care Task Force. At the time of publication, H. Campbell is employed by the College of Nurses of Ontario, A. Russell is employed by the Michener Institute for Applied Health Sciences, and B. Melnick is employed by Atlantis Systems Corporation.

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham, C.E., Deal, K., Rimas, H. et al. Using Conjoint Analysis to Model the Preferences of Different Patient Segments for Attributes of Patient-Centered Care. Patient-Patient-Centered-Outcome-Res 1, 317–330 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/1312067-200801040-00013

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/1312067-200801040-00013