Abstract

Background

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) and the Juster scale are accepted methods for the prediction of individual purchase probabilities. Nevertheless, these methods have seldom been applied to a social decision-making context.

Objective

To gain an overview of social decisions for a decision-making population through data triangulation, these two methods were used to understand purchase probability in a social decision-making context.

Methods

We report an exploratory social decision-making study of pharmaceutical subsidy in Australia. A DCE and selected Juster scale profiles were presented to current and past members of the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee and its Economic Subcommittee.

Results

Across 66 observations derived from 11 respondents for 6 different pharmaceutical profiles, there was a small overall median difference of 0.024 in the predicted probability of public subsidy (p = 0.003), with the Juster scale predicting the higher likelihood. While consistency was observed at the extremes of the probability scale, the funding probability differed over the mid-range of profiles. There was larger variability in the DCE than Juster predictions within each individual respondent, suggesting the DCE is better able to discriminate between profiles. However, large variation was observed between individuals in the Juster scale but not DCE predictions.

Conclusions

It is important to use multiple methods to obtain a complete picture of the probability of purchase or public subsidy in a social decision-making context until further research can elaborate on our findings. This exploratory analysis supports the suggestion that the mixed logit model, which was used for the DCE analysis, may fail to adequately account for preference heterogeneity in some contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Harris AH, Buxton M, O’Brien B, et al. Using economic evidence in reimbursement decisions for health technologies: experience of 4 countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2001; 1(1): 7–12

Peckham S. Primary care purchasing: are integrated primary care provider/purchasers the way forward? Pharmacoeconomics 1999 Mar; 15(3): 209–16

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26(8): 661–77

Viney R, Lancsar E, Louviere J. Discrete choice experiments to measure consumer preferences for health and healthcare. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2002; 2(4): 319–26

Dolan P, Olsen JA, Menzel P, et al. An inquiry into the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Econ 2003; 12: 545–51

Gold MR, Franks P, Siegelberg T, et al. Does providing cost-effectiveness information change coverage priorities for citizens acting as social decision-makers? Health Policy 2007; 83: 65–72

Al MJ, Feenstra T, Brouwer WBF. Decision makers’ views on health care objectives and budget constraints: results from a pilot study. Health Policy 2004 Oct; 70(1): 33–48

Menon D, Stafinski T, Stuart G. Access to drugs for cancer: does where you live matter? Can J Public Health 2005 Nov-Dec; 96(6): 454–8

Gallego G, Taylor SJ, Brien J-AE. Priority setting for high cost medications (HCMs) in public hospitals in Australia: a case study. Health Policy 2007 Nov; 84(1): 58–66

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Social value judgements: principles for the development of NICE guidance. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008

Nord E, Street A, Richardson J, et al. The significance of age and duration of effect in social evaluation of health care. Health Care Anal 1996 May; 4(2): 103–11

Rodriguez-Miguez E, Pinto-Prades JL. Measuring the social importance of concentration or dispersion of individual health benefits. Health Econ 2002 Jan; 11(1): 43–53

Ubel PA, Loewenstein G, Scanlon D, et al. Individual utilities are inconsistent with rationing choices: a partial explanation of why Oregon’s cost-effectiveness list failed. Med Decis Making 1996 Apr-Jun; 16(2): 108–16

Green C. On the societal value of health care: what do we know about the person trade-off technique? Health Econ 2001 Apr; 10(3): 233–43

Bryan S, Roberts T, Heginbotham C, et al. QALY-maximisation and public preferences: results from a general population survey. Health Econ 2002 Dec; 11(8): 679–93

Schwappach DLB. Does it matter who you are or what you gain? An experimental study of preferences for resource allocation. Health Econ 2003 Apr; 12(4): 255–67

Johnson FR, Backhouse M. Eliciting stated preferences for health-technology adoption criteria using paired comparisons and recommendation judgements. Value Health 2006; 9(5): 303–11

Tappenden P, Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, et al. A stated preference binary choice experiment to explore NICE decision making. Pharmacoeconomics 2007; 25(8): 685–93

Green C, Gerard K. Exploring the social value of health-care interventions: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Health Econ 2009 Nov 25; 18(8): 951–76

Swancutt DR, Greenfield SM, Wilson S. Women’s colposcopy experience and preferences: a mixed methods study. BMC Womens Health 2008; 8: 2

Pitchforth E, Watson V, Tucker J, et al. Models of intrapartum care and women’s trade-offs in remote and rural Scotland: a mixed-methods study. BJOG 2008 Apr; 115(5): 560–9

Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess 2001 Mar; 5(5): 1–186

Furnham A. Factors relating to the allocation of medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 1996; 11(3): 615–24

Furnham A, Meader N, McClelland A. Factors affecting nonmedical participants’ allocation of scarce medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 1998; 13(4): 735–46

Bowling A, Jacobson B, Southgate L. Explorations in consultation of the public and health professionals on priority setting in an inner London health district. Soc Sci Med 1993 Oct; 37(7): 851–7

Olsen JA, Donaldson C. Helicopters, hearts and hips: using willingness to pay to set priorities for public sector health care programmes. Soc Sci Med 1998 Jan; 46(1): 1–12

Ratcliffe J. Public preferences for the allocation of donor liver grafts for transplantation. Health Econ 2000 Mar; 9(2): 137–48

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003; 2(1): 55–64

Marshall D, Bridges JFP, Hauber B, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health: how are studies being designed and reported? Patient 2010; 3(4): 249–56

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. Epub 2010 Dec 19

Farrar S, Ryan M, Ross D, et al. Using discrete choice modelling in priority-setting: an application to clinical service developments. Soc Sci Med 2000; 50: 63–75

Juster TF. Consumer buying intentions and purchase probability: an experiment in survey design. J Am Stat Assoc 1966 Sep; 61(315): 658–96

Day D, Gan B, Gendall P, et al. Predicting purchase behaviour. Market Bull 1991 May; 2: 18–30

McDonald H, Alpert F. Using the Juster Scale to predict adoption of an innovative product. Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference; 2001 Dec 1-5; Auckland NZ

Wright M, MacRae M. Bias and variability in purchase intention scales. J Acad Market Sci 2007 Dec; 35(4): 617–24

Street DJ, Burgess L, Louviere J. Quick and easy choice sets: constructing optimal and nearly optimal stated choice experiments. Int J Res Market 2005; 22: 459–70

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005

Wright M, Sharp A, Sharp B. Market statistics for the Dirichlet model: using the Juster scale to replace panel data. Int J Res Market 2002 Mar; 19(1): 81–90

Uncles M, Lee D. Brand purchasing by older consumers: an investigation using the Juster scale and the Dirichlet model. Market Lett 2006; 17(1): 17–29

Brennan M. Constructing demand curves from purchase probability data: an application of the Juster scale. Market Bull 1995; 6: 51–8

Brennan M, Charbonneau J. Constructing demand curves: a comparison of two procedures using the Juster scale. Market Bull 2005; 16 (Research note 7): 1–6

Brennan M, Esslemont D. The accuracy of the Juster Scale for predicting purchase rates of branded, fast-moving consumer goods. Market Bull 1994; 5 (Research note 1): 47–52

Garland R. Estimating customer defection in personal retail banking. Int J Bank Market 2002; 20(7): 317–24

Patterson PG. Demographic correlates of loyalty in a service context. J Serv Market 2007; 21(2): 112–21

Reid M, Wood A. An investigation into blood donation intentions among non-donors. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sector Market 2008; 13: 31–43

Hoek J, Maubach N, Gendall P. Effects of cigarette on-pack warning labels on smokers’ perceptions and behaviour. In: Lees MC, Davis T, Gregory G, editors. Asia-Pacific advances in consumer research. Sydney, Australia: Association for Consumer Research, 2006: 173–80

McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press, 1973: 105–42

McFadden D. Econometric models of probabilistic choice. In: Manski C, McFadden D, editors. Structural analysis of discrete data with economic applications. Boston: MIT Press, 1981

Thurstone L. A law of comparative judgement. Psychol Rev 1927; 4: 273–86

Manski CF. The structure of random utility models. Theory Decision 1977; 8: 229–54

Baumgartner H, Steenkamp J-BE. Response Styles in Marketing Research: A Cross-National Investigation. Journal of Marketing Research 2001; 38(2): 143–56

Brazier J, Green C, McCabe C, et al. Use of visual analog scales in economic evaluation. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2003 Jun; 3(3): 293–302

AIHW. Australia’s health 2008. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008. Report No.: AUS 99

OECD. Social expenditure: aggregated data. OECD social expenditure statistics database [online]. Available from URL: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/data/social-expenditure/aggregated-data_data-00166-en?isPartOf=/content/datacollection/els-socx-data-en [Accessed 2011 Nov 30]

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household expenditure survey, Australia: summary of results, 2003–04. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 Feb 15. Report No.: 6530.0

Australian Government Productivity Commission. Impacts of advances in medical technology in Australia: research report. Melbourne: Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2005

Taylor RS, Drummond MF, Salkeld G, et al. Development of fourth hurdle policies around the world. In: Freemantle N, Hill S, editors. Evaluating pharmaceuticals for health policy and reimbursement. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004: 67–87

Mitchell A. Antipodean assessment: activities, actions and achievements. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2002; 18: 203–12

Hjelmgren J, Berggren F, Andersson F. Health economic guidelines: similarities, differences and some implications. Value Health 2001 May-Jun; 4(3): 225–50

Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (version 4.3). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2008 Dec

Sansom L. The subsidy of pharmaceuticals in Australia: processes and challenges. Aust Health Rev 2004 Nov 8; 28(2): 194–205

Harris AH, Hill SR, Chin G, et al. The role of value for money in public insurance coverage decisions for drugs in Australia: a retrospective analysis 1994-2004. Med Decis Making 2008 Sep-Oct; 28(5): 713–22

Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pbs-general-listing-committee2.htm [Accessed 2010 Sep 9]

Whitty JA, Scuffham PA, Rundle-Thiele SR. Public and decision maker stated preferences for pharmaceutical subsidy decisions: a pilot study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2011; 9(2): 73–9

Greene W. NLOGIT [computer program]. version 4.0.1. Plainview, NY: Econometric Software, Inc., 2007

Greene WH. NLOGIT version 4.0: reference guide. Plain-view, NY: Econometric Software, Inc., 2007

Drummond M, McGuire A, editors. Economic evaluation in health care: merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001

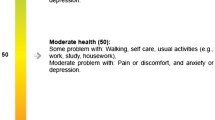

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for Euroqol health states. Med Care 1997; 35(11): 1095–108

Scuffham PA, Whitty JA, Mitchell A, et al. The use of QALY weights for QALY calculations: a review of industry submissions requesting listing on the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 2002-4. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26(4): 297–310

Torrance GW. Social preferences for health states: an empirical evaluation of three measurement technques. Socioecon Plann Sci 1976; 10: 129–36

Fiebig DG, Keane MP, Louviere JJ, et al. The generalized multinomial logit model: accounting for scale and coefficient heterogeneity. Marketing Science 2010; 29: 393–421

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken without external funding. Jennifer Whitty gratefully acknowledges the support of Griffith University and School of Medicine research scholarships to undertake this study. We thank Dorte Gyrd-Hansen and two anonymous reviewers for providing valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors are not aware of any conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. Paul Scuffham leads a research group contracted to undertake evaluations for the PBAC and Jennifer Whitty undertakes evaluations for that group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitty, J.A., Rundle-Thiele, S.R. & Scuffham, P.A. Insights from triangulation of two purchase choice elicitation methods to predict social decision making in healthcare. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 10, 113–126 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11597100-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11597100-000000000-00000