Abstract

Background: In November 2009, all children in the Netherlands from 6 months up to 4 years of age were indicated to receive the Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine. Fever is a common adverse event following immunization in children. Pandemrix®, an inactivated, split-virus influenza A (H1N1) vaccine, was used for this age group. A clinical study mentioned in the Summary of Product Characteristics of Pandemrix® found an increased reactogenicity after the second dose in comparison with the first dose, particularly in the rate of fever. In the Netherlands, this adverse reaction was a point of concern for the parents or caregivers of these children.

Objective: To investigate the course and height of fever following the first and second dose of Pandemrix® in children aged from 6 months up to 4 years. The secondary aim was to evaluate the use of an online survey during a vaccination campaign.

Design: Survey-based descriptive study.

Setting: Adverse drug reaction reporting database of the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre (Lareb).

Participants: Parents or caregivers (n = 839) of vaccinated children who reported fever to Lareb following the first immunization with Pandemrix®. Questionnaires were sent by email to parents or caregivers of eligible children following the first and second doses of Pandremix®.

Main Outcome Measures: Time between vaccination and the occurrence of fever, the maximum measured temperature, the occurrence of other adverse events after first and second vaccination, the decision to get the second vaccination and the social implication of the fever in terms of absence from work, nursery or school, and hospitalization.

Results: Following the first vaccination against Influenza A (H1N1), the height of the fever was between 39.0 and 40.0°C in 359/639 (56.2%) of the children. In most of these children (235/639 [36.8%]), the onset of fever was between 6 and 12 hours following vaccination. 450/639 (70.4%) children recovered within 2 days. Of the 539 responders to the second questionnaire, 380 (70.5%) received the second vaccination against Influenza A (H1N1) and 213 (56.1%) of these children experienced fever again. The height of the fever was significantly lower (t-test; p = 0.001) and the duration was significantly shorter (Pearson’s Chisquare; p = 0.002) in comparison with the first vaccination. The height of the fever after the first vaccination was associated with the decision to receive the second vaccination (t-test; p = 0.000). In the studied group, 342 (53.5%) parents or caregivers needed to stay home from work and 405 (63.4%) children stayed home from nursery or school due to fever following the first vaccination.

Conclusions: The results of this study can be used in future vaccination campaigns to be able to inform people in an evidence-based manner about the risks and benefits of the vaccine and to avoid unnecessary concern and negative media attention. This could contribute to improved immunization levels. A web-based survey is demonstrated to be a useful tool to quickly gather information about a current safety concern and consequently inform the public to support an ongoing vaccination campaign.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vaccines are one of the most effective ways to control a pandemic. Therefore, after the discovery of the Influenza A (H1N1) virus in April 2009, immunization programmes against this virus were introduced in more than 50 countries.[1] In August 2010, the Director-General of the WHO declared that the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic has moved into the post-pandemic period.[2] As the virus continues to circulate, vaccination remains important to reduce morbidity and mortality.[3] In the Netherlands, the Health Council, a scientific advisory board for the government, prioritized the target groups most at risk of infection with the virus. Initially, this concerned people of medical risk, people above 60 years of age and healthcare professionals coming into close contact with patients.[4] At the beginning of November 2009, all children from 6 months up to 4 years of age were also indicated as people in special need of the vaccine.[5] The Health Council concluded the assumed benefits outweighed the potential risks of the vaccine in this age group.[5] However, the limited available vaccine safety data was a reason for concern for the general public. Concerns have been raised about multiple factors, such as the possible association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with Influenza A (H1N1) vaccination in the US in 1976,[6] and possible risks associated with the adjuvants used.

Fever is a common adverse event following immunization, especially in children.[7,8] Pandemrix®, the vaccine used for this age group in the Netherlands, is an inactivated, split-virus influenza vaccine.[9] A clinical study evaluated the reactogenicity in children aged 6–35 months who received half the adult dose following a day 0 and day 21 vaccine schedule. An increase in reactogenicity after the second dose was observed, particularly in the rate of fever.[9] Hereafter, at the beginning of December 2009, the European Medicines Agency produced a press release on this adverse reaction and advised prescribers and parents to monitor the temperature of the vaccinated child closely and, if necessary, take measures to lower the fever.[10] In the Netherlands, this adverse reaction was also reported frequently following the first dose of Pandemrix®. Between 24 and 30 November 2009, fever was reported 1608 times to the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre (Lareb). 685 of these reports mentioned a body temperature above 39.0°C. More than 800 000 children were invited to receive the Influenza A (H1N1) immunization. Of these children, 71% received the first dose and 59% received both doses. The number of reports did not exceed the incidence rate for fever found in clinical trials;[9] however, the number of reports did indicate the social concern for this possible adverse event and it raised the question about the time-to-onset and course of this reaction. The answer to this question was needed quickly to be able to use the information during the vaccination campaign.

The aim of this study was to investigate the course and height of fever following the first and second dose of Pandemrix® in children aged from 6 months up to 4 years. The secondary aim was to evaluate the use of an online survey during a vaccination campaign to provide quick insight into the course of a possible safety concern and therefore be able to support the vaccination campaign while it is being executed.

Methods

The characteristics of the episodes of fever following immunization were examined in a retrospective study by using web-based questionnaires.

In the Netherlands, the first round of the Influenza A (H1N1) vaccination campaign for children from 6 months up to 4 years of age was held from 23 to 28 November 2009. Both healthcare professionals and patients were encouraged to report adverse events following immunization (AEFI) to Lareb by using an online report form. A detailed description of the method of processing, analysing and performing signal detection on the reports of AEFI in relation to the pandemic influenza vaccines in the Netherlands by Van Puijenbroek et al.[11] can be found in this issue of Drug Safety. One of the obligatory fields in this form was the e-mail address, so that reporters could be easily contacted when follow-up information was needed.

On 26 November, all received reports concerning fever in association with the first vaccination with Pandemrix®, in children born after 1 January 2005, originating from patients, were selected in the Lareb database. Fever was considered to be the elevation of at least one measured body temperature above 38.0°C, measured at any site, utilizing any validated device.[7,8]

The e-mail addresses from all reports that met the criteria mentioned above were selected from the database. Online questionnaires were developed in SurveyMonkey, a web-based survey tool (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.adisonline.com/DSZ/A34).[12] The first questionnaire was sent by e-mail on 30 November 2009. In the accompanying e-mail message, parents or caregivers of the children were asked to participate. In this survey, questions were asked about the episode of fever after the first vaccination. In addition, people were asked about their willingness to fill in a second questionnaire, which would be sent following the second dose of Pandemrix®. This second questionnaire was only sent to people who indicated that they agreed to participate a second time. The second survey was sent, according to the minimum 21-day interval between the two doses of the vaccine, recommended at that time,[9] on 23 December 2009. No reminder was sent for the two questionnaires.

Both questionnaires collected data regarding the height of the temperature, method of measuring, the time interval between vaccination and the occurrence of fever and recovery, other accompanying adverse events, possible other causes for the fever and the impact of the fever on absence from nursery or school, or work in the case of the parents or caregivers. The second questionnaire, in addition to these questions, asked if the children received the second vaccination and, if not, what the reason for this decision was.

Descriptive analyses were carried out in SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

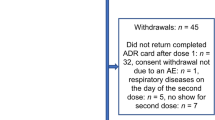

Eight hundred and thirty-nine parents or caregivers who reported fever to Lareb following the first immunization with the Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine in children aged from 6 months up to 4 years of age were selected from the database and sent the first questionnaire. 692 completed the first questionnaire (response rate 82.5%). In the first questionnaire, 339/692 (49.0%) were boys and 353 (51.0%) were girls. 53/692 (7.7%) were excluded from the analyses as either an unknown temperature (n = 30 [4.3%]) or a temperature below 38.0°C (n = 23 [3.3%]) was reported in these cases, but they were not excluded for the second survey. 12/692 (1.7%) responders indicated they did not wish to participate in a second survey or did not answer this question. 680/692 (98.3%) responders were asked to complete a second questionnaire 3 weeks later. The response rate for the second questionnaire was 79.3% (n = 539) of the 680 responders.

Course and Height of Fever Following the First Immunization

Three hundred and fifty-nine of 639 children with fever (56.2%) had a reported temperature between 39.0 and 40.0°C following the first immunization with the Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine. The temperature was measured rectally in 495/639 (77.5%) or in the ear in 132 (20.7%) of the cases. In 235/639 (36.8%) children, the fever started between 6 and 12 hours after vaccination. 450/639 (70.4%) children were reported to have recovered from the fever within 2 days after onset. 477/639 (74.6%) parents or caregivers treated the child with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or another unspecified antipyretic drug to lower the temperature after the first vaccination. 349/639 (54.6%) parents or caregivers reported injection-site reactions. Other reported adverse events were list-lessness (n = 564/639 [88.3%]), drowsiness (200/639 [31.3%]), decreased appetite (471/639 [73.7%]) and vomiting (121/639 [18.9%]). In 15/639 (2.3%) children the fever led to a febrile convulsion. 101 (15.8%) of the parents or caregivers indicated that there could have been another possible explanation for the increased body temperature.

Course and Height of Fever Following the Second Immunization

Of the 539 people who responded to the second questionnaire, 380 (70.5%) received the second immunization against Influenza A (H1N1). Of these children, 213/380 (56.1%) had fever again following the second vaccination. Fourteen of these 213 children (6.6%) did not measure their temperature and 15 (7.0%) reported a temperature under 38.0°C and were therefore excluded from the analyses. Of the 184 children remaining for analysis, 98 (53.3%) people reported a temperature between 38.0 and 39.0°C. In 82/184 (44.6%) of the children, the fever occurred between 6 and 12 hours after vaccination. 166/184 (90.2%) of the children recovered from the fever within 2 days and 42 (22.8%) recovered within 12 hours. In three (1.6%) children, the fever led to a febrile convulsion. Thirteen (7.1%) of the parents or caregivers indicated that there could have been another possible explanation for the increased body temperature.

In the children who had fever following both the first and second vaccinations, the mean reported temperature after the second dose was significantly lower than it was following the first dose (t-test; p = 0.001) [figure 1]. The site at which the temperature was measured did not differ after the first and second vaccinations (Pearson Chisquare [χ2]; p = 0.176). The time between vaccination and the onset of fever did not differ following the first and second doses (χ2; p = 0.685). When fever reoccurred after the second vaccination, the duration was significantly lower (χ2; p = 0.002) [figure 2].

Decision to Receive the Second Vaccination

Of the 159 (29.5%) people who refused a second vaccination, 27 reported a temperature between 38.0 and 39.0°C, and 124 reported a temperature above 39.0°C following the first vaccination (figure 3). 105 (66.0%) indicated that the severity of adverse events after the first vaccination was the most important reason for this decision. This reason was significantly more frequently reported in the group with hyperpyrexia, defined as a temperature above 39.0°C, than in the group that reported a temperature between 38.0 and 39.0°C following the first vaccination (t-test; p=0.000).

Impact of Fever on Children and Parents or Caregivers

Following the first immunization, 405/639 (63.4%) parents or caregivers reported that the child stayed at home from nursery or school. 342/639 (53.5%) parents or caregivers needed to take a day off from work. Of the 184 children who had fever following the second immunization, 73 (39.7%) parents or caregivers reported the child stayed at home from nursery or school and 53 (28.8%) parents or caregivers needed to take a day off from work. Observation or admission to hospital was reported in four (0.6%) children after the first vaccination and in none of the children after the second vaccination (table I).

Discussion This study demonstrated that 43.9% of the children from 6 months up to 4 years of age who had fever following the first vaccination against Influenza A (H1N1) did not have fever following the second immunization and, if they did, the course of the fever was less severe. The height of the temperature was significantly lower and the duration was significantly shorter in comparison with the first vaccination. Height of the temperature after the first vaccination was associated with the decision to receive the second vaccination. In the studied group, 342 (53.5%) of parents or caregivers needed to stay home from work and 405 (63.4%) children stayed home from nursery or school due to fever following the first vaccination, which are parameters for the social impact of this event.

As mentioned in the Background section, fever following immunization is a common adverse event and it is therefore not surprising that this reaction was reported frequently to Lareb. Parents are often worried about the risk of complications of fever,[13] such as febrile convulsions. Eskerud et al.[14] demonstrated that one-third of individuals questioned in their study unjustly believed that a temperature above 40.5°C is lethal. Therefore, it is important that people are well informed about, and thus prepared for, the possible consequences of fever following immunization. In the Netherlands, all parents whose children received the vaccine were given a leaflet with information about possible adverse reactions and the possibility of reporting adverse events to the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre. However, the information leaflet produced by the Community Health Services used after the first immunization did not mention fever as a possible adverse reaction despite the fact that the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) of Pandemrix®[9] mentioned an incidence of more than 10% for this possible adverse reaction. This, together with negative media attention towards this vaccine, might explain the concerns of parents, caregivers and healthcare professionals. To prevent this happening again after the second vaccination, fever was added to the patient leaflet that was used for the second dose.

Fever is a common event in children, with an incidence in the Netherlands of 122 per 1000 in the first year of life and 41.5 per 1000 per year in children aged from 1 to 5 years.[15] Therefore, it cannot be excluded that in some cases the occurrence of fever following immunization might be coincidental and due to a concurrent infectious disease instead of a causal relationship with the administered vaccine. Another point we came across during the study is that people reported fever although the maximum measured temperature was below 38.0°C, which shows that the medical definition of fever is not equal to the general perception of this reaction. In this study we excluded these cases from further analyses. A limitation of this study is that only children who had fever following the first vaccination were investigated. Hence, we cannot draw conclusions about the children who did not have fever following the first vaccination, but who might have experienced fever after immunization with the second dose. This is also the reason why this study does not supply incidence rates of the occurrence of fever following immunization with Pandemrix®. A prospective cohort study would be needed to give insight into this group of children and to predict the incidence of fever following immunization with the Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine.

As far as we know, this is the first report describing the course and height of fever following immunization with Influenza A (H1N1) in children from 6 months up to 4 years of age in the 2009 influenza pandemic. This study showed that fever following the first vaccination is not necessarily followed by fever following the second vaccination. If fever occurs after the first and second vaccinations, the course is milder following the second dose. These data correspond with the results of an antigenecity and reactogenicity trial of the influenza A/New Jersey/76 (H1N1) virus vaccine in children. The children in this study experienced a demonstrable reactivity after the initial dose of the vaccine and were largely free of symptoms following the second dose. The authors suggested that this observation might have been dependent upon acquired immune experience.[16] In contrast, the results conflict with the results of the clinical trial mentioned in the SPC of Pandemrix®[9] where an increased reactogenicity following the second dose was found in children between 6 and 35 months of age. This contrast might be explained by the fact that in the current study only the children who developed fever following the first vaccination were investigated and not the children who did not have fever following the initial dose, but who might have had this adverse reaction following the second immunization. The impact of fever following immunization in the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) vaccination campaign in terms of absence from nursery or school and work, and on the decision to get the second vaccination, was considerable.

Conclusions

The results of this study can be used in future vaccination campaigns to inform people in an evidence-based manner about the risks and benefits of the vaccine and to avoid unnecessary worrying and negative media attention. This could contribute to improved immunization levels. Keeping the public better informed could help people in making the decision to receive the vaccines and thereby support public health, especially in the case of a future pandemic. A web-based survey has shown to be a useful tool to quickly gather information about a current safety concern and consequently inform the public to support an ongoing vaccination campaign.

References

World Health Organization. Statement from WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety about the safety profile of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccines. 18 December 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/cp164_2009_1612_gacvs_h1n1_vaccine_safety.pdf [Accessed 2010 Feb 22]

World Health Organization. Director-General’s opening statement at virtual press conference: H1N1 in post-pandemic period. 10 August 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2010/h1n1_vpc_20100810/en/index.html [Accessed 2010 Sep 12]

World Health Organization. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 briefing note 23. WHO recommendations for the post-pandemic period. 10 August 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/briefing_20100810/en/index.html [Accessed 2010 Sep 12]

Dutch Health Council. Vaccination against pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) 2009: target groups and prioritization (1). 17 August 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites/default/files/200910_0.pdf [Accessed 2010 Feb 22]

Dutch Health Council. Vaccination against pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) 2009: target groups and prioritization (3). 9 November 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites/default/files/Briefadvies%20influenza%20A_H1N1%202009%20DEEL3R%20_gewijzigd%20dd20nov2009_0.pdf [Accessed 2010 Feb 22]

Haber P, Sejvar J, Mikaeloff Y, et al. Vaccines and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Drug Saf 2009; 32(4): 309–23

Kohl KS, Marcy SM, Blum M, et al. Fever after immunization: current concepts and improved future scientific understanding. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39(3): 389–94

Michael MS, Kohl KS, Dagan R, et al. Fever as an adverse event following immunization: case definition and guidelines of data collection, analysis, and presentation. Vaccine 2004; 22(5–6): 551–6

European Medicines Agency. Pandemrix®: summary of product characteristics [online]. Available from URL: http://eudrapharm.eu/eudrapharm/showDocument?documentId=6519788735704300414 [Accessed 2010 Feb 22]

European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency advises of risk of fever in young children following vaccination with Pandemrix. 4 December 2009 [press release; online]. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/general/direct/pr/78440409en.pdf [Accessed 2010 Feb 22]

van Puijenbroek EP, Broos N, van Grootheest K. Monitoring adverse events of the vaccination campaign against influenza A (H1N1) in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2010; 33(12): 1097–108

SurveyMonkey [online]. Available from URL: http://www.surveymonkey.com/ [Accessed 2010 Aug 24]

Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years? Pediatrics 2001; 107(6): 1241–6

Eskerud JR, Hoftvedt BO, Laerum E. Fever: knowledge, perception and attitudes: results from a Norwegian population study. Fam Pract 1991; 8(1): 32–6

Van der Linden M. Second national study to diseases and performances in the general practitioner practice: symptoms and diseases in the population and the general practitioner practice. Utrecht/Bilthoven: NIVEL/RIVM, 2004

Wright PF, Thompson J, Vaughn WK, et al. Trials of influenza A/New Jersey/76 virus vaccine in normal children: an overview of age-related antigenicity and reactogenicity. J Infect Dis 1977; 136 Suppl.: S731–41

Acknowledgements

No sources of external funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Broos, N., van Puijenbroek, E.P. & van Grootheest, K. Fever Following Immunization with Influenza A (H1N1) Vaccine in Children. Drug-Safety 33, 1109–1115 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11539280-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11539280-000000000-00000