Abstract

Background The Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) rivastigmine and galantamine have been approved for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in the Netherlands. Differences between ChEIs regarding persistence or the use of effeCtive doses in daily Clinical practice have been observed. However, most studies assessing ChEI discontinuation and associated determinants have been Conducted in North America and there is a lack of knowledge about ChEI discontinuation and its determinants in daily Clinical practice in Europe.

Objectives To assess ChEI discontinuation in daily practice in the Netherlands and to seek its determinants, including suboptimal utilization.

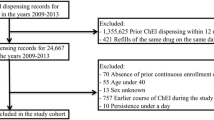

Methods A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Dutch PHARMO Record Linkage System. Included patients were aged ≥50 years at first dispensing of a ChEI, had a first dispensing of a ChEI between 1998 and 2008, had a prior medication history of 12 months and had at least one subsequent dispensing of any kind of medication. The proportion of patients who discontinued ChEIs over 3 years was determined. Cox regression was used to assess determinants for early (≤6 months) discontinuation and, separately, for late discontinuation during a subsequent 30-month follow-up among those persisting with treatment for >6 months.

Results At 6 months, 30.8% of 3369 study patients had discontinued ChEIs, compared with 59.0% after 3 years. Thirty-five percent of patients taking rivastigmine reached the WHO-defined daily dose compared with 80% taking galantamine. At 6 months, compared with regular-dose rivastigmine, low-dose rivastigmine or low-dose galantamine was associated with an increased risk of early discontinuation, whereas regular-dose galantamine was associated with a decreased risk, as was concurrent use of cardiac medications, drugs for Parkinson’s disease, propulsives, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines. Associations of ChEI type/dose or comedications with discontinuation among patients persisting for >6 months differed somewhat from associations with discontinuation before 6 months.

Conclusions Fewer patients taking rivastigmine than those taking galantamine reached recommended doses. Furthermore, patients taking rivastigmine had an increased risk of early discontinuation compared with patients taking galantamine. Adverse effects leading to treatment intolerance and suboptimal utilization may have been contributing factors to these observed differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ott A, Breteler MM, van Harskamp F, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: association with education. The Rotterdam study. BMJ 1995; 310(6985): 970–3

Georges J. The availability of anti-dementia drugs in Europe. Alzheimer Europe/European Neurological Disease, 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.touchneurology.com/files/article_pdfs/neuro_7413 [Accessed 2010 Apr 29]

Rodda J, Morgan S, Walker Z. Are cholinesterase inhibitors effective in the management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease? A systematic review of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine. Int Psychogeriatr 2009; 21(5): 813–24

Rockwood K, Dai D, Mitnitski A. Patterns of decline and evidence of subgroups in patients with Alzheimer’s disease taking galantamine for up to 48 months. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23(2): 207–14

Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Mamdani M, et al. Representation of patients with dementia in clinical trials of donepezil. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 11(2): e274–85

Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, et al. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ 2008; 336(7653): 1114–7

Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: WHO, 2003 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf [Accessed 2010 Apr 29]

Morgan SG, Yan L. Persistence with hypertension treatment among community-dwelling BC seniors. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 11(2): e267–73

Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148(5): 379–97

Herrmann N, Binder C, Dalziel W, et al. Persistence with cholinesterase inhibitor therapy for dementia: an observational administrative health database study. Drugs Aging 2009; 26(5): 403–7

Dybicz SB, Keohane DJ, Erwin WG, et al. Patterns of cholinesterase-inhibitor use in the nursing home setting: a retrospective analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006; 4(2): 154–60

Johnell K, Fastbom J. Concurrent use of anticholinergic drugs and cholinesterase inhibitors: register-based study of over 700,000 elderly patients. Drugs Aging 2008; 25(10): 871–7

Lu CJ, Tune LE. Chronic exposure to anticholinergic medications adversely affects the course of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11(4): 458–61

Wright RM, Roumani YF, Boudreau R, et al. Effect of central nervous system medication use on decline in cognition in community-dwelling older adults: findings from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(2): 243–50

Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(7): 808–13

Elliott WJ. Improving outcomes in hypertensive patients: focus on adherence and persistence with antihypertensive therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2009; 11(7): 376–82

Mauskopf JA, Paramore C, Lee WC, et al. Drug persistency patterns for patients treated with rivastigmine or donepezil in usual care settings. J Manag Care Pharm 2005; 11(3): 231–51

Fillit HM, Doody RS, Binaso K, et al. Recommendations for best practices in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in managed care. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006; 4Suppl. A: S9–24; quiz S5-S8

Kogut SJ, El-Maouche D, Abughosh SM. Decreased persistence to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy with concomitant use of drugs that can impair cognition. Pharmacotherapy 2005; 25(12): 1729–35

Herrmann N, Gill SS, Bell CM, et al. A population-based study of cholinesterase inhibitor use for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55(10): 1517–23

Massoud F, Dorais M, Charbonneau C, et al. Drug utilization review of cholinesterase inhibitors in Quebec. Can J Neurol Sci 2008; 35(4): 508–9

Herings RM, Bakker A, Stricker BH, et al. Pharmaco-mor-bidity linkage: a feasibility study comparing morbidity in two pharmacy based exposure cohorts. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992; 46(2): 136–40

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD index. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health [online]. Available from URL: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ [Accessed 2010 Jun 22]

Gardarsdottir H, Heerdink ER, Egberts AC. Potential bias in pharmacoepidemiological studies due to the length of the drug free period: a study on antidepressant drug use in adults in the Netherlands. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15(5): 338–43

Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Kirshner M, et al. Serum anticholinergic activity in a community-based sample of older adults: relationship with cognitive performance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60(2): 198–203

Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14(1): e1–26

Ferreri F, Agbokou C, Gauthier S. Cardiovascular effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2007; 163(10): 968–74

Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45(2): 197–203

Clark DO, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. A chronic disease score with empirically derived weights. Med Care 1995; 33(8): 783–95

Frankfort SV, Appels BA, de Boer A, et al. Discontinuation of rivastigmine in routine clinical practice. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20(12): 1167–71

Hosmer DWJ, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1999

Qaseem A, Snow V, Cross Jr JT, et al. Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148(5): 370–8

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie. Richtlijn Diagnostiek en medikamenteuze behandeling van dementie. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications BV, 2005: 147 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.vanzuidencommunications.nl [Accessed 2010 Jun 22]

Arbouw ME, Movig KL, Guchelaar HJ, et al. Discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole in patients with Parkinson’s disease: clinical practice versus clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 64(10): 1021–6

Lyle S, Grizzell M, Willmott S, et al. Treatment of a whole population sample of Alzheimer’s disease with donepezil over a 4-year period: lessons learned. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008; 25(3): 226–31

Mucha L, Shaohung S, Cuffel B, et al. Comparison of cholinesterase inhibitor utilization patterns and associated health care costs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Manag Care Pharm 2008; 14(5): 451–61

Suh DC, Thomas SK, Valiyeva E, et al. Drug persistency of two cholinesterase inhibitors: rivastigmine versus done-pezil in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2005; 22(8): 695–707

Bottiggi KA, Salazar JC, Yu L, et al. Concomitant use of medications with anticholinergic properties and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: impact on cognitive and physical functioning in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 15(4): 357–9

Lemstra AW, Kuiper RB, Schmand B, et al. Identification of responders to rivastigmine: a prospective cohort study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008; 25(1): 60–6

Arlt S, Lindner R, Rosler A, et al. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging 2008; 25(12): 1033–47

Acknowledgements

This study received financial support from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) [research fellowship for E. Kröger], from the division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacotherapy at Utrecht University (UIPS) and the Centre d’excellence sur le vieillissement de Québec (CEVQ), Québec, Canada. The division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacotherapy at Utrecht University, which employs T. Egberts and P. Souverein, has received unrestricted funding for pharmacoepidemiological research from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, the private-public funded Top Institute Pharma (www.tipharma.nl, which includes co-funding from universities, government, and industry), the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board and the Dutch Ministry of Health. The CIHR, UIPS or CEVQ were not involved in the study design, conduct or analyses, or in the preparation of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study. The results of this study were presented at the 25th Anniversary International Conference for Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, August 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kröger, E., van Marum, R., Souverein, P. et al. Discontinuation of Cholinesterase Inhibitor Treatment and Determinants thereof in the Netherlands. Drugs Aging 27, 663–675 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11538230-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11538230-000000000-00000