Abstract

This review provides practical information on and clinical reasons for switching children and young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) from neurostimulants to atomoxetine, detailing currently available evidence, and switching options. The issue is of particular relevance following recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and European ADHD guidelines endorsing the use of atomoxetine, along with the stimulants methylphenidate and dexamphetamine, in the management of ADHD in children and adolescents in the UK.

The selective norepinephrine (noradrenaline) reuptake inhibitor, atomoxetine, is a non-stimulant drug licensed for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents, and in adults who have shown a response in childhood. Following the once-daily morning dose, its therapeutic effects extend through the waking hours, into late evening, and in some patients, through to early the next morning. Atomoxetine may be considered for patients who are unresponsive or incompletely responsive to stimulant treatment, have co-morbid conditions (e.g. tics, anxiety, depression), and have sleep disturbances or eating problems, for patients in whom stimulants are poorly tolerated, and for situations where there is potential for drug abuse or diversion. Atomoxetine has been shown to be effective in relapse prevention and there is suggestion that atomoxetine may have a positive effect on global functioning; specifically health-related quality of life, self-esteem, and social and family functioning.

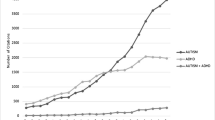

According to one study, approximately 50% of non-responders to methylphenidate will respond to atomoxetine therapy and approximately 75% of responders to methylphenidate will also respond to atomoxetine. Atomoxetine may be initiated by a schedule of dose increases and cross-tapering with methylphenidate. A slow titration schedule with divided doses minimizes the impact of adverse events within the first several weeks of treatment. Atomoxetine may be co-administered with methylphenidate during the switching period without undue concern for adverse events, such as cardiovascular effects (although monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate is necessary). Atomoxetine may be discontinued abruptly and patients may miss the occasional dose without rebound effects or discontinuation syndrome. A trial period of at least 6–8 weeks, perhaps longer, is recommended before evaluation of the overall tolerability and efficacy of atomoxetine.

We conclude that patients with ADHD can be switched from neurostimulants, specifically methylphenidate, to atomoxetine, and may benefit from symptom improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of tradenames is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Swanson JM, Sergeant JA, Taylor E, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Lancet 1998; 351(9100): 429–33

Barkley RA, DuPaul GJ, McMurray MB. Comprehensive evaluation of attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity as defined by research criteria. J Consult Clin Psychology 1990; 58(6): 775–89

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, et al. The adolescents outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria-III. Mother-child interactions family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1991; 32(2): 233–55

Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148(5): 564–77

Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. Pharmacotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the life cycle. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35(4): 409–32

Klein RG, Mannuzza S. Long-term outcome of hyperactive children: a review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30(3): 383–837

Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child 2005; 90Suppl. 1: i2–7

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Methylphenidate, atomoxetine and dexamphetamine for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Review of Technology Appraisal 13. Technology Appraisal 98 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/download.aspx?.o=TA098guidance [Accessed 2006 May 12]

Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40(2): 168–79

Pliszka SR. Nonstimulant treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Spectrums 2003; 8(4): 253–8

Barkley RA, McMurray MB, Edelbrock CS, et al. Side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic, placebo-controlled evaluation. Pediatrics 1990; 86(2): 184–92

Swanson J. Compliance with stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: issues and approaches for improvement. CNS Drugs 2003; 17(2): 117–31

Prasad S. A new paradigm for developing drugs in children: atomoxetine as a model. Arch Dis Child 2005; 90Suppl. 1: i13–6

Summary of Product Characteristics. Strattera® Atomoxetine HC1. Eli Lilly and Company, 2006 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.medicines.org.uk/searchresult.aspx?.search=atomoxetine [Accessed 2007 Nov 26]

Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Santosh P, et al. Long-acting medications for the hyperkinetic disorders. A systematic review and European treatment guideline. Eur Child Adol Psychiatry 2006; 15: 476–95

Michelson D, Allen A, Busner J, et al. Once daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised, placebo controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(11): 1896–901

Kelsey DK, Sumner CR, Casat CD, et al. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including an assessment of evening and morning behavior: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics 2004; 114: el–e8 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/1/e1 [Accessed 006 Aug 2]

Kratochvil CJ, Vaughan BS, Daughton JM, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics 2004; 4: 601–11

Barton J. Atomoxetine: a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Dis Child 2005; 90Suppl. 1: i26–9

Michelson D, Buitelaar JK, Danckaerts M, et al. Relapse prevention in Pediatric patients with ADHD treated with atomoxetine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43(7): 896–904

Allen AJ, Kurlan RM, Gilbert DL, et al. Atomoxetine treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD and comorbid tic disorders. Neurology 2005; 65(12): 1941–9

Shatkin JP. Atomoxetine for the treatment of Pediatric nocturnal enuresis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14: 443–37

Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics 2001; 108(5): e83

Prasad S, Poole L. Assessing quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: SUNBEAM an open comparative study of atomoxetine and standard therapy. Patient Reported Outcomes Newsletter 2006; 36: 16–9

Prasad S, Harpin V, Poole L, et al. A multicentre, randomised, open-label study of atomoxetine compared with standard current therapy in UK children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23: 379–94

Wernicke JF, Kratochvil CJ. Safety profile of atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63Suppl. 12: 50–5

Wernicke JF, Faries D, Girod D, et al. Cardiovascular effects of atomoxetine in children, adolescents, and adults. Drug Saf 2003; 26(10): 729–40

Faraone SV, Biederman J. Neurobiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44(10): 951–8

Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of noradrenaline and dopamine in the prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsy-chopharmacology 2002; 27: 699–711

Sauer JM, Ponsler GD, Mattiuz EL, et al. Disposition and metabolic fate of atomoxetine hydrochloride: the role of CYP2D6 in human disposition and metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2003; 31(5): 98–107

Kratochvil CJ, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R, et al. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in children with ADHD: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41(7): 776–84

Sauer J-M, Ring BJ, Witcher JW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44(6): 571–90

Belle DJ, Ernest CS, Sauer JM, et al. Effect of potent CYP2D6 inhibition by paroxetine on atomoxetine pharmacokinetics. J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 42(11): 1219–27

Sauer JM, Long AJ, Ring B, et al. Atomoxetine hydrochloride: clinical drug-drug interaction prediction and outcome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004; 308(2): 410–8

Kelly RP, Yeo KP, Teng CH, et al. Hemodynamic effects of acute administration of atomoxetine and methylphenidate. J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 45(7): 851–5

Summary of product characteristics: Ritalin® methylphenidate hydrochloride. Novartis, 2005 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.medicines.org.uk/searchresult.aspx?.search=ritalin [Accessed 2006 Aug 2]

Steer C. Managing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: unmet needs and future directions. Arch Dis Child 2005; 90Suppl. 1: 119–25

Palumbo D, Spencer T, Lynch J, et al. Emergence of tics in children with ADHD: impact of once-daily OROS methylphenidate therapy. J Child Adolesc Psycho-pharmacol 2004; 14(2): 185–94

Swanson J, Gupta S, Lam A, et al. Development of a new once-a-day formulation of methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: proof-of-concept and proof-of-product studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60(2): 204–111

Dopfner M, Gerber WD, Banaschewski T, et al. Comparative efficacy of once-a-day extended-release methylphenidate, two-times-daily immediate-release methylphenidate, and placebo in a laboratory school setting. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 13Suppl. 1: I93–101

Kelsey DK, Sumner CR, Casat CD, et al. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including an assessment of evening and morning behavior: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics 2004; 114(1): e1–8

Stein D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Blank S, et al. Sleep disturbances in adolescents with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Learn Disabil 2002; 35(3): 268–75

Sangal RB, Owens J, Allen AJ, et al. Effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on sleep in children with ADHD. Sleep 2006; 29(12): 1573–85

Heil SH, Holmes HW, Bickel WK, et al. Comparison of the subjective, placebo, and psychomotor effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate in light drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 67: 149–56

Quintana H, Cherlin E, Duesenberg D, et al. Transitioning from methylphenidate or amphetamine to atomoxetine in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a preliminary tolerability and efficacy study. Clin Ther 2007; 29(6): 1168–77

Michelson D. Results from a double-blind study of atomoxetine, OROS methylphenidate, and placebo. The 51st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 2004 Oct 19–24; Washington, DC. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; Suppl. 20D: 49

Nissen S. ADHD drugs and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(14): 1445–8

Greenhill L, Halperin JM, Abikoff H. Stimulant medications. J Am Acad child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38(5): 503–12

Schweizer E, Richels K, Case WG, et al. Long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines: II. Effects of gradual taper. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47(10): 908–15

Noyes Jr R, Garvey MJ, Cook B, et al. Controlled discontinuation of benzodiazepine treatment for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148(4): 517–23

Garland EJ. Pharmacotherapy of adolescent attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: challenges, choices and caveats. J Psychopharmacol 1998; 12(4): 385–95

Wernicke JF, Adler L, Spencer T, et al. Changes in symptoms and adverse events after discontinuation of atomoxetine in children and adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a prospective, placebo-controlled assessment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24(1): 30–5

Keating GM, McClellan K, Jarvis B. Methylphenidate (OROS® formulation). CNS Drugs 2001; 15(6): 495–500

Joyce PR, Nicholls MG, Donald RA. Methylphenidate increases heart rate, blood pressure and plasma epinephrine in normal subjects. Life Sci 1984; 34(18): 1707–11

Brown TE. Atomoxetine and stimulants in combination for treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: four case reports. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol 2004; 14(1): 129–35

Steer CR. Atomoxetine treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review and analysis of decision making and clinical outcomes in an outpatient clinic setting. J Psychopharmacol 2006; 20(5): A34

Attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorders in children and young people. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2001 Jun. Publication no. 52; sect. 5.4: 16

Pliszka SR, Crismon ML, Hughes CW, et al. The Texas children’s medication algorithm project: revision of the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45(6): 642–57

Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, et al. Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52(3): 173–88

Data on file, Eli Lilly & Co., 2006

Spencer T, Heiligenstein JH, Biederman J, et al. Results from 2 proof-of-concept, placebo-controlled studies of atomoxetine in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63(12): 1140–7

Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, et al. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53(2): 112–20

PhRMA/FDA/AASLD. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity white paper: postmarketing considerations, 2000 Nov [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/livertox/postmarket.pdf [Accessed 2006 Oct 13]

Thase ME. Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3744 depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59: 502–8

Haller CA, Benowitz NL Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1833–8

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Susan Libretto for her contributions to the editing and preparation of this manuscript, and Ms Leigh Mathieson, Ms Nicola Savill, and Ms Lesley Reese for the project management of this review article. Dr Suyash Prasad is a former employee of Eli Lilly where the majority of this work was conducted. He is a current employee of the Cromwell Hospital, London, UK and Genzyme Therapeutics, Oxford, UK. Dr Chris Steer is a clinical investigator and member of the Eli Lilly ADHD advisory board. This work was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company; however, the authors have received no funding for their writing contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prasad, S., Steer, C. Switching from Neurostimulant Therapy to Atomoxetine in Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Pediatr-Drugs 10, 39–47 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00148581-200810010-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00148581-200810010-00005