Abstract

Current Management Strategies in Type 2 Diabetes

Since between 2 and 5% of the population aged less than 70 years and up to 15% of elderly individuals are affected by type 2 diabetes, this disease is responsible for an unacceptably high rate of premature morbidity and mortality. One of the main aims of the treatment of type 2 diabetes is to reduce the incidence of specific and macrovascular complications. The lessons learned from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) can be applied to type 2 diabetes in order to prevent specific complications, including diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. Various observational studies have suggested that good control of plasma glucose levels is equally important for preventing macrovascular complications; the correction of common cardiovascular risk factors, such as lipid abnormalities, high blood pressure and smoking, is undeniably necessary.

The natural history of type 2 diabetes is one of a progressive disorder resulting from both insulin resistance and a decline in pancreatic β-cell function, which lead to defective insulin secretion. Diet and exercise are effective in many patients at the onset of the disease. Generally speaking, the treatment of type 2 diabetes begins with a non-drug approach, without which the disease will progress rapidly. However, when these nonpharmacological measures fail, treatment with different oral drugs can be initiated: a single pharmacological class can be used in the first stage and 2 classes combined in the second stage. The choice of one or another oral hypoglycaemic agent will depend upon the different and complementary mechanism of action of each class. Sulphonylureas stimulate residual insulin secretion. Metformin inhibits overproduction of glucose by the liver. Acarbose delays the intestinal absorption of polysaccharides. Thiazolidinediones reduce insulin resistance. When the ‘maximal’ oral treatment fails, the final therapeutic step is to start insulin treatment, initially according to the ‘bed-time’ regimen, followed by a regimen of multi-injections.

Two approaches exist regarding the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The first recommends strict glucose control achieved by intensive insulin therapy, even at the risk of frequent weight gain, contrasted with a more liberal approach to glycaemia levels, which allows less aggressive insulin therapy. Our arguments favour the former attitude.

Résumé

La prévalence du diabète de type 2 se situe à environ 2 à 5% chez les moins de 70 ans et atteint 15% chez les personnes plus âgées. Cette maladie est ainsi à l’origine d’un excès considérable de morbidité et de mortalité prématurées. La prise en charge du diabète de type 2 a pour objectif de réduire les complications spécifiques et macrovasculaires de la maladie. Les leçons du DCCT (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial) peuvent s’appliquer au diabète de type 2 pour la prévention des complications spécifiques liées, notamment, à la microangiopathie. Différentes études d’intervention suggèrent qu’une normalisation glycémique est également importante vis-à-vis du risque macrovasculaire, en plus de la nécessaire prise en charge des facteurs de risque classiques. L’histoire naturelle du diabète de type 2 est celle d’une aggravation progressive par déficit de l’insulinosécrétion associé à un certain degré d’insulinorésistance. Lorsque régime et exercice physique ne sont plus suffisants, différents agents oraux peuvent être proposés, d’abord en monothérapie puis en bithérapie. Les sulfamides stimulent l’insulinosécrétion résiduelle, la metformine inhibe l’hyperproduction hépatique du glucose, l’acarbose retarde l’absorption intestinale des sucres complexes, les thiazolidinediones diminuent l’insulinorésistance. Lorsque le traitement oral “maximal” est insuffisant, l’insuline peut être proposée, d’abord dans sa modalité “bed-time” (au coucher), puis en multi-injections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Références

Kahn CR. An introduction to type II diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diab 1995; 2: 283–4.

Eastman RC, Gorden P. The DCCT: implications for diabetes treatment. Diabetes Rev 1994; 2: 263–71.

Colwell JA. DCCT findings: applicability and implications for NIDDM. Diabetes Rev 1994; 2: 277–91.

Hirsch IB, Gaster B. The effects of improved glycemic control on complications in type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 134–40.

Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, et al. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 434–44.

Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of maturity-onset diabetes mellitus and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151: 1141–7.

Welin L, Eriksson H, Larsson B, et al. Hyperinsulinaemia is not a major coronary risk factor in elderly men. The study of men born in 1913. Diabetologia 1992; 35: 766–70.

Uusitupa MIJ, Niskanen LK, Siitonen O, et al. Ten-year cardiovascular mortality in relation to risk factors and abnormalities in lipoprotein composition in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetologia 1993; 36: 1175–84.

Kuusisto J, Mykkänen L, Pyörälä K, et al. NIDDM and its metabolic control predict coronary heart disease in elderly subjects. Diabetes 1994; 43: 960–7.

Gall MA, Borch-Johnsen K, Hougaard P, et al. Albuminuria and poor glycemic control predict mortality in NIDDM. Diabetes 1995; 44: 1303–9.

Turner RC, Millns H, Neil HAW, et al. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 23). BMJ 1998; 316: 823–8.

Jensen-Urstad KJ, Reichard PG, Rosfors JS, et al. Early atherosclerosis is retarded by improved long-term blood glucose control in patients with IDDM. Diabetes 1996; 45: 1253–8.

Barrett-Connor E. Does hyperglycemia really cause coronary heart disease? Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1620–3.

Alberti KGMM, Cries FA, Jervell J, et al. A desktop guide for the management of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM): an update. Diabetic Med 1994; 11: 899–909.

Brun JM, Drouin P, Berthezene F, et al. Dyslipidémies du patient diabétique. Recommandations de l’ALFEDIAM. [Dyslipidemia in the diabetic patient. Recommendations of ALFEDIAM (French Language Association for the Study of Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases)] Diabète Métab 1995; 21: 59–62.

Pyörälä K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, et al. Cholesterol lowering with simvastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 614–20.

Recommendations. Nutrition principles for the management of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 490–518.

Recommendations. Exercise and NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1990; 13: 785–90.

Kang J, Robertson RJ, Hagberg JM, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on glucose and insulin metabolism in obese individuals and obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1996; 19: 341–9.

UK prospective diabetes study 16. Overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes 1995; 44(11): 1249–58.

Wollen N, Bailey CJ. Inhibition of hepatic glucogenesis by metformin: synergism with insulin. Biochem Pharmacol 1988; 37: 353–8.

Argaud D, Roth H, Wiernsperger N, et al. Metformin decreases gluconeogenesis by enhancing the pyruvate kinase flux in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem 1993; 213(3): 1341–8.

Stumvoll M, Nurjhan N, Perriello G, et al. Metabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(9): 550–4.

Jackson RA, Hawa MI, Jaspan JB, et al. Mechanism of metformin action in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes 1987; 36(5): 632–40.

Lalau JD, Lacroix C, Compagnon P, et al. Role of metformin accumulation in metformin associated lactic acidosis. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 779–84.

Inzucchi SE, Maggs DG, Spollett GR, et al. Efficacy and metabolic effects of metformin and troglitazone in type II diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 867–72.

Spiegelman BM. PPAR-g: adipogenic regulator and thiazolidine receptor. Diabetes 1998; 47: 507–14.

Harrington W, Brown K, Hashim M, et al. Antidiabetic effects of PPAR-γ activators are not enhanced by addition of β3 adrenergic stimulation in db/db mice. Diabetes 1996; 45: 75A.

Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Insulin stimulates adipogenic differentiation through modification and activation of PPAR-γ. Diabetes 1996; 45: 224A.

Hu E, Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Transdifferentiation of myoblasts by the adipogenic transcription factors PPAR-γ and C/EPB-α. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 856–60.

Spiegelman B, Flier JS. Adipogenesis and obesity: rounding out the big picture. Cell 1996; 87: 377–89.

Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Thiazolidinediones in the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 1996; 45: 1661–9.

Campbell IW, Menzies DG, Chalmers J, et al. One year comparative trial of metformin and glipizide in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabète Métab 1994; 21: 394–400.

Groop LC. Sulfonylureas in NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1993; 15: 737–54.

Trovati M, Burzacca S, Mularoni E, et al. Occurrence of low blood glucose concentrations during the afternoon in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients on oral hypoglycaemic agents: importance of blood glucose monitoring. Diabetologia 1991; 34: 662–7.

Lebovitz HE. Stepwise and combination drug therapy for the treatment of NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 1542–4.

Stenman S, Melander A, Groop P-H, et al. What is the benefit of increasing the sulfonylurea dose? Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 169–72.

Lewis GF, Steiner G. Acute effects of insulin in the control of VLDL production in humans. Implications for the insulin-resistant state. Diabetes Care 1996; 19: 390–3.

Nathan DM, Roussel A, Godine JE. Glyburide or insulin for metabolic control in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. A randomized, double-blind study. Ann Intern Med 1988; 108: 334–40.

Henry RR, Gumbiner B, Ditzler T, et al. Intensive conventional insulin therapy for type II diabetes. Metabolic effects during a 6-mo outpatient trial. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 21–31.

Jarrett RJ. Why is insulin not a risk factor for coronary heart disease? Diabetologia 1994; 37: 947–57.

Leonetti F, Iozzo P, Giaccari A, et al. Absence of clinically overt atherosclerotic vascular disease and adverse changes in cardiovascular risk factors in 70 patients with insulinoma. J Endocrinol Invest 1993; 16: 875–80.

Effects of hypoglycemic agents on vascular complications in patients with adult-onset diabetes. VIII. Evaluation of insulin therapy: final report. Diabetes 1982; 31 Suppl. 5: 1–81.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group. Effect of intensive diabetes management on macrovascular events and risk factors in the diabetes control and complication trial. Am J Cardiol 1995; 75: 894–903.

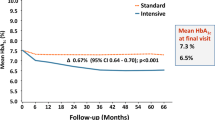

Abraira C, Colwell JA, Nuttall FQ, et al. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study on glycemic control and complications in type II diabetes ( VA CSDM). Results of the feasibility trial. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study in Type II Diabetes. Diabetes Care 1995; 18(8): 1113–23.

Malmberg K, Ryden L, Efendic S, et al. On behalf of the DIGAMI Study Group. Randomized trial of insulin-glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI Study): effects on mortality at 1 year. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995; 26: 57–65.

Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, et al. The effect of insulin treatment on insulin secretion and insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1985; 34: 222–34.

Forster G, Wadden TA, Leurer ID. Controlled trial of the metabolic effects of a very low caloric diet: short and long term effects. Am J Clin Nutr 1990; 51: 167–72.

Puhakainen I, Taskinen M-R, Yki-Jarvinen H. Comparison of acute daytime and nocturnal insulinization on diurnal glucose homeostasis in NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 805–9.

Shank ML, Del Prato S, deFronzo R. Bedtime insulin/daytime glipizide. Effective therapy for sulfonylurea failures in NIDDM. Diabetes 1995; 44: 165–72.

Yki-Jarvinen H, Kauppila M, Kujansuu E, et al. Comparison of insulin regimens in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1426–33.

Henry RR, Gumbiner B, Ditzler T, et al. Intensive conventional therapy for type II diabetes. Metabolic effects during a 6-month outpatient trial. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 21–31.

Scheen AJ, Lefebvre PJ. Oral antidiabetic agents. A guide to selection. Drugs 1998; 55(2): 225–36.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charbonnel, B. Stratégies actuelles de prise en charge du diabète de type 2. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 4 (Suppl 1), 13–28 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-199804001-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-199804001-00002