Abstract

Neutropenia is a serious hematologic toxicity of myelosuppressive chemotherapy. The discovery that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) could stimulate the production of neutrophils was followed by the purification and molecular cloning of filgrastim (Neupogen®), the human recombinant form of the protein, between 1984 and 1986. In this article, we review 20 years of clinical literature with filgrastim and the more recent experience with pegfilgrastim (Neulasta®) to support the delivery of chemotherapy. The earliest clinical studies of filgrastim showed that it produces immediate transient leukopenia followed by a sustained, dose-dependent increase in circulating neutrophils. In the two registrational studies of filgrastim, the cumulative incidence of febrile neutropenia (FN) was reduced by about 50% compared with placebo. Subsequent clinical trials and meta-analyses established that primary prophylaxis with filgrastim (beginning in the first cycle of chemotherapy) reduced the incidence of FN, FN-related hospitalizations, intravenous anti-infective use, infection-related mortality, and the need for chemotherapy dose modification, compared with placebo or no treatment, in many tumor types. Pegfilgrastim, formed by the addition of a polyethylene glycol molecule to filgrastim, has comparable efficacy to filgrastim when administered only once per chemotherapy cycle. High-level evidence indicates that both filgrastim and pegfilgrastim improve the likelihood of completing dose-dense and dose-intense chemotherapy. The most recent guidelines from three international cancer organizations, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the US National Comprehensive Cancer Network, are in agreement that filgrastim or pegfilgrastim should be given prophylactically when the risk of FN with a chemotherapy regimen is ≥20%, or when the risk is 10–20% and the patient has other risk factors for FN. The development of filgrastim and pegfilgrastim has revolutionized oncology practice. Prophylactic use of these agents has enabled development of more aggressive chemotherapy regimens, including dose-dense chemotherapy, and treatment of a broader range of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, et al. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med 1966 Feb; 64(2): 328–40

Lieschke GJ, Bell D, Rawlinson W, et al. Empiric single agent or combination antibiotic therapy for febrile episodes in neutropenic patients: an overview. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989; 25Suppl. 2: S37–42

Pizzo PA, Robichaud KJ, Wesley R, et al. Fever in the pediatric and young adult patient with cancer: a prospective study of 1001 episodes. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982 May; 61(3): 153–65

Schimpff SC. Empiric antibiotic therapy for granulocytopenic cancer patients. Am J Med 1986 May 30; 80(5c): 13–20

Smith TJC, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2006 Jul 1; 24(19): 3187–205

Durand-Zaleski I, Vainchtock A, Bogillot O. L’utilisation de la base nationale PMSI pour déterminer le côut d’un symptôme: le cas de la neutropénie fébrile. J Econ Med 2007; 25: 269–80

Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS, et al. Incidence, cost, and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer 2005 May 1; 103(9): 1916–24

Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer 2006 May 15; 106(10): 2258–66

Courtney DM, Aldeen AZ, Gorman SM, et al. Cancer-associated neutropenic fever: clinical outcome and economic costs of emergency department care. Oncologist 2007 Aug; 12(8): 1019–26

Nicola NA, Begley CG, Metcalf D. Identification of the human analogue of a regulator that induces differentiation in murine leukaemic cells. Nature 1985 Apr 18–24; 314(6012): 625–8

Welte K, Platzer E, Lu L, et al. Purification and biochemical characterization of human pluripotent hematopoietic colony-stimulating factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985 Mar; 82(5): 1526–30

Nomura H, Imazeki I, Oheda M, et al. Purification and characterization of human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). EMBO J 1986 May; 5(5): 871–6

Souza LM, Boone TC, Gabrilove J, et al. Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: effects on normal and leukemic myeloid cells. Science 1986 Apr 4; 232(4746): 61–5

Nagata S, Tsuchiya M, Asano S, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNA for human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Nature 1986 Jan 30–Feb 5; 319(6052): 415–8

Demetri GD, Griffin JD. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and its receptor. Blood 1991 Dec 1; 78(11): 2791–808

Colgan SP, Gasper PW, Thrall MA, et al. Neutrophil function in normal and Chediak-Higashi syndrome cats following administration of recombinant canine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Exp Hematol 1992 Nov; 20(10): 1229–34

Glaspy JA, Golde DW. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): preclinical and clinical studies. Semin Oncol 1992 Aug; 19(4): 386–94

Lieschke GJ, Burgess AW. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. N Engl J Med 1992 Jul 2; 327(1): 28–35

Cebon J, Layton JE, Maher D, et al. Endogenous haemopoietic growth factors in neutropenia and infection. Br J Haematol 1994 Feb; 86(4): 265–74

Welte K, Gabrilove J, Bronchud MH, et al. Filgrastim (r-metHuG-CSF): the first 10 years. Blood 1996 Sep 15; 88(6): 1907–29

Bronchud MH, Scarffe JH, Thatcher N, et al. Phase I/II study of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1987 Dec; 56(6): 809–13

Dührsen U, Villeval JL, Boyd J, et al. Effects of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on hematopoietic progenitor cells in cancer patients. Blood 1988 Dec; 72(6): 2074–81

Gabrilove JL, Jakubowski A, Fain K, et al. Phase I study of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. J Clin Invest 1988 Oct; 82(4): 1454–61

Morstyn G, Campbell L, Souza LM, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on neutropenia induced by cytotoxic chemotherapy. Lancet 1988 Mar 26; I(8587): 667–72

Gabrilove JL, Jakubowski A, Scher H, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutropenia and associated morbidity due to chemotherapy for transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. N Engl J Med 1988 Jun 2; 318(22): 1414–22

Crawford J, Ozer H, Stoller R, et al. Reduction by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of fever and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 1991 Jul 18; 325(3): 164–70

Trillet-Lenoir V, Green J, Manegold C, et al. Recombinant granulocyte colony stimulating factor reduces the infectious complications of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 1993; 29A: 319–24

Rader M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor use in patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: clinical and economic benefits. Oncology (Williston Park) 2006 Apr; 20(5 Suppl. 4): 16–21

Mucenski JW, Shogan JE. Maximizing the outcomes in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy through optimal use of colony-stimulating factor. J Manag Care Pharm 2003 Mar–Apr; 9Suppl. 2: 10–4

Muhonen T, Jantunen I, Pertovaara H, et al. Prophylactic filgrastim (G-CSF) during mitomycin-C, mitoxantrone, and methotrexate (MMM) treatment for metastatic breast cancer: a randomized study. Am J Clin Oncol 1996 Jun; 19(3): 232–4

Pettengell R, Gurney H, Radford JA, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to prevent dose-limiting neutropenia in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a randomized controlled trial. Blood 1992 Sep 15; 80(6): 1430–6

Zinzani PL, Pavone E, Storti S, et al. Randomized trial with or without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as adjunct to induction VNCOP-B treatment of elderly high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 1997 Jun; 89(11): 3974–9

Osby E, Hagberg H, Kvaloy S, et al. CHOP is superior to CNOP in elderly patients with aggressive lymphoma while outcome is unaffected by filgrastim treatment: results of a Nordic Lymphoma Group randomized trial. Blood 2003 May 15; 101(10): 3840–8

Epelbaum R, Faraggi D, Ben-Arie Y, et al. Survival of diffuse large cell lymphoma: a multivariate analysis including dose intensity variables. Cancer 1990 Sep 15; 66(15): 1124–9

Kwak LW, Halpern J, Olshen RA, et al. Prognostic significance of actual dose intensity in diffuse large-cell lymphoma: results of a tree-structured survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 1990 Jun; 8(6): 963–77

Hryniuk W, Levine MN. Analysis of dose intensity for adjuvant chemotherapy trials in stage II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986 Aug; 4(8): 1162–70

Lepage E, Gisselbrecht C, Haioun C, et al. Prognostic significance of received relative dose intensity in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients: application to LNH-87 protocol. The GELA. (Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte). Ann Oncol 1993 Sep; 4(8): 651–6

Lee KW, Kim DY, Yun T, et al. Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in elderly patients: comparison of treatment outcomes between young and elderly patients and the significance of doxorubicin dosage. Cancer 2003 Dec 15; 98(12): 2651–6

Bosly A, Bron D, Van Hoof A, et al., for the Lymphoma Dose Project: a National Study. Achievement of optimal average relative dose intensity and correlation with survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with CHOP. Ann Hematol 2008 Apr; 87(4): 277–83

Pettengell R, Schwenkglenks M, Bosly A. Association of reduced relative dose intensity and survival in lymphoma patients receiving CHOP-21 chemotherapy. Ann Hematol 2008 May; 87(5): 429–30

Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Moliterni A, et al. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer: the results of 20 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med 1995 Apr 6; 332(14): 901–6

Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al., for The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998 Aug 19; 90(16): 1205–11

Mayers C, Panzarella T, Tannock IF. Analysis of the prognostic effects of inclusion in a clinical trial and of myelosuppression on survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. Cancer 2001 Jun 15; 91(12): 2246–57

Bonadonna G, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, et al. 30 years’ follow up of randomised studies of adjuvant CMF in operable breast cancer: cohort study. BMJ 2005 Jan 29; 330(7485): 217

Bonneterre J, Roché H, Kerbrat P, et al. Epirubicin increases long-term survival in adjuvant chemotherapy of patients with poor-prognosis, node-positive, early breast cancer: 10-year follow-up results of the French Adjuvant Study Group 05 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2005 Apr 20; 23(12): 2686–93

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005 May 14–20; 365(9472): 1687–717

Chirivella I, Bermejo B, Insa A, et al. Optimal delivery of anthracycline-based chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting improves outcome of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009 Apr; 114(3): 479–84

Hryniuk W, Frei III E, Wright FA. A single scale for comparing dose-intensity of all chemotherapy regimens in breast cancer: summation dose-intensity. J Clin Oncol 1998 Sep; 16(9): 3137–47

Jakobsen A, Berglund A, Glimelius B, et al. Dose-effect relationship of bolus 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2002; 41(6): 525–31

Scheithauer W, Kornek GV, Raderer M, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II trial of two different schedules of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003 Apr 1; 21(7): 1307–12

Ardizzoni A, Favaretto A, Boni L, et al. Platinum-etoposide chemotherapy in elderly patients with small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized multicenter phase II study assessing attenuated-dose or full-dose with lenograstim prophylaxis: a Forza Operativa Nazionale Italiana Carcinoma Polmonare and Gruppo Studio Tumori Polmonari Veneto (FONICAP-GSTPV) study. J Clin Oncol 2005 Jan 20; 23(3): 569–75

Lyman GH, Dale DC, Crawford J. Incidence and predictors of low dose-intensity in adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: a nationwide study of community practices. J Clin Oncol 2003 Dec 15; 21(24): 4524–31

Lyman GH, Dale DC, Friedberg J, et al. Incidence and predictors of low chemotherapy dose-intensity in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a nationwide study. J Clin Oncol 2004 Nov 1; 22(21): 4302–11

Donnelly S, Epstein J, Al-Bussam N, et al. Filgrastim experience in diverse nonmyeloid malignancies: a prospective study in community oncology practice [poster no. 728]. 39th Annual Meeting, American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2003 May 31–Jun 3; Chicago (IL)

Pettengell R, Schwenkglenks M, Leonard R, et al. Neutropenia occurrence and predictors of reduced chemotherapy delivery: results from the INC-EU Prospective Observational European Neutropenia Study. Support Care Cancer 2008 Nov; 16(11): 1299–309

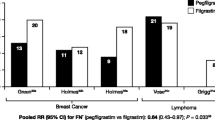

Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on febrile neutropenia and mortality in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2007 Jul 20; 25(21): 3158–67

Aapro MS, Cameron DA, Pettengell R, et al. EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphomas and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 2006 Oct; 42(15): 2433–53

Repetto L, Biganzoli L, Koehne CH, et al. EORTC Cancer in the Elderly Task Force guidelines for the use of colony-stimulating factors in elderly patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 2003 Nov; 39(16): 2264–72

Norton L, Simon R. Tumor size, sensitivity to therapy, and design of treatment schedules. Cancer Treat Rep 1977 Oct; 61(7): 1307–17

Citron ML, Berry DA, Cirrincione C, et al. Randomized trial of dose-dense versus conventionally scheduled and sequential versus concurrent combination chemotherapy as postoperative adjuvant treatment of node-positive primary breast cancer: first report of Intergroup Trial C9741/Cancer and Leukemia Group B Trial 9741. J Clin Oncol 2003 Apr 15; 21(8): 1431–9

Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Kloess M, et al. Two-weekly or 3-weekly CHOP chemotherapy with or without etoposide for the treatment of young patients with good-prognosis (normal LDH) aggressive lymphomas: results of the NHL-B1 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood 2004 Aug 1; 104(3): 626–33

Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Kloess M, et al. Two-weekly or 3-weekly CHOP chemotherapy with or without etoposide for the treatment of elderly patients with aggressive lymphomas: results of the NHL-B2 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood 2004 Aug 1; 104(3): 634–41

Wunderlich A, Kloess M, Reiser M, et al. Practicability and acute haematological toxicity of 2- and 3-weekly CHOP and CHOEP chemotherapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results from the NHL-B trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 2003 Jun; 14(6): 881–93

Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol 2008 Feb; 9(2): 105–16

Amgen Inc. Neupogen® (filgrastim): summary of product characteristics. Breda: Amgen Europe BV, 2008 Aug 13 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.amgen.co.uk/pdfs/Neupogen_SmpC_Aug_2008_vials_and_singleject.pdf [Accessed 2009 May 18]

Amgen Inc. Neupogen® (filgrastim): US prescribing information. Thousand Oaks (CA): Amgen Inc., 2007 Sep [online]. Available from URL: http://www.neupogen.com/pdf/Neupogen_PI.pdf [Accessed 2009 May 18]

Hershman D, Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome following use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors during breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007 Feb 7; 99(3): 196–205

Sung L, Nathan PC, Lange B, et al. Prophylactic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor decrease febrile neutropenia after chemotherapy in children with cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2004 Aug; 22(16): 3350–6

Relling MV, Boyett JM, Blanco JG, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and the risk of secondary myeloid malignancy after etoposide treatment. Blood 2003 May; 101(10): 3862–7

Johnston E, Crawford J, Blackwell S, et al. Randomized, dose-escalation study of SD/01 compared with daily filgrastim in patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000 Jul; 18(13): 2522–8

Amgen Inc. Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim): US prescribing information [online]. Thousand Oaks (CA): Amgen Inc., 2008 Nov [online]. Available from URL: http://www.neulasta.com/pdf/Neulasta_PI.pdf [Accessed 2009 May 18]

Holmes FA, O’Shaughnessy JA, Vukelja S, et al. Blinded, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate single administration pegfilgrastim once per cycle versus daily filgrastim as an adjunct to chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III/IV breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002 Feb 1; 20(3): 727–31

Green MD, Koelbl H, Baselga J, et al. A randomized double-blind multicenter phase III study of fixed-dose single-administration pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2003 Jan; 14(1): 29–35

Misset JL, Dieras V, Gruia G, et al. Dose-finding study of docetaxel and doxorubicin in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1999 May; 10(5): 553–60

Grigg A, Solal-Celigny P, Hoskin P, et al. Open-label, randomized study of pegfilgrastim vs daily filgrastim as an adjunct to chemotherapy in elderly patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003 Sep; 44(9): 1503–8

Vose JM, Crump M, Lazarus H, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of pegfilgrastim compared with daily filgrastim after chemotherapy for lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2003 Feb 1; 21(3): 514–9

George S, Yunus F, Case D, et al. Fixed-dose pegfilgrastim is safe and allows neutrophil recovery in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003 Oct; 44(10): 1691–6

Vogel CL, Wojtukiewicz MZ, Carroll RR, et al. First and subsequent cycle use of pegfilgrastim prevents febrile neutropenia in patients with breast cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2005 Feb 20; 23(6): 1178–84

Chan S, Friedrichs K, Noel D, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus doxorubicin in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999 Aug; 17(8): 2341–54

Bear HD, Anderson S, Brown A, et al. The effect on tumor response of adding sequential preoperative docetaxel to preoperative doxorubicin and cyclo-phosphamide: preliminary results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-27. J Clin Oncol 2003 Nov 15; 21(22): 4165–74

Siena S, Piccart MJ, Holmes FA, et al. A single dose of pegfilgrastim per chemotherapy cycle allows most patients to receive an average relative dose intensity of at least 85% [abstract no. 535]. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2002; 76Suppl. 1: S134

Siena S, Piccart MJ, Holmes FA, et al. A combined analysis of two pivotal randomized trials of a single dose of pegfilgrastim per chemotherapy cycle and daily Filgrastim in patients with stage II–IV breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2003 May–Jun; 10(3): 715–24

Burstein HJ, Parker LM, Keshaviah A, et al. Efficacy of pegfilgrastim and darbepoetin alfa as hematopoietic support for dose-dense every-2-week adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005 Nov 20; 23(33): 8340–7

Brusamolino E, Rusconi C, Montalbetti L, et al. Dose-dense R-CHOP-14 supported by pegfilgrastim in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a phase II study of feasibility and toxicity. Haematologica 2006 Apr; 91(4): 496–502

Wolf M, Bentley M, Marlton P, et al. Pegfilgrastim to support CHOP-14 in elderly patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2006 Nov; 47(11): 2344–50

Balducci L, Al-Halawani H, Charu V, et al. Elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy benefit from first-cycle pegfilgrastim. Oncologist 2007 Dec; 12(12): 1416–24

Romieu G, Clemens M, Mahlberg R, et al. Pegfilgrastim supports delivery of FEC-100 chemotherapy in elderly patients with high risk breast cancer: a randomized phase 2 trial. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007 Oct; 64(1): 64–72

Filgrastim and pegfilgrastim estimated patient exposure numbers as of February 2008. Thousand Oaks (CA): Amgen, 2008. (Data on file)

Pinto L, Liu Z, Doan Q, et al. Comparison of pegfilgrastim with filgrastim on febrile neutropenia, grade IV neutropenia and bone pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin 2007 Sep; 23(9): 2283–95

Wolff AC, Jones RJ, Davidson NE, et al. Myeloid toxicity in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy with pegfilgrastim support. J Clin Oncol 2006 May 20; 24(15): 2392–4; author reply 2394-5

Wildiers H, Dirix L, Neven P, et al. Delivery of adjuvant sequential dose-dense FEC-Doc to patients with breast cancer is feasible, but dose reductions and toxicity are dependent on treatment sequence. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009 Mar; 114(1): 103–12

US National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Myeloid growth factors: the National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology, version 1.2008. January 2, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org [Accessed 2008 Jan 8]

vonMinckwitz G, Kummel S, du Bois A, et al. Pegfilgrastim +/− ciprofloxacin for primary prophylaxis with TAC (docetaxel/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy for breast cancer: results from the GEPARTRIO study. Ann Oncol 2008 Feb; 19(2): 292–8

vonMinckwitz G, Schwenkglenks M, Skacel T, et al. Febrile neutropenia and related complications in breast cancer patients receiving pegfilgrastim primary prophylaxis versus current practice neutropaenia management: results from an integrated analysis. Eur J Cancer 2009 Mar; 45(4): 608–17

López A, Alonso JD, Gómez-Codina J, et al., on behalf of the ENIA Study Group. Febrile neutropenia in lymphoma patients is associated with substantial resource use and healthcare costs in clinical practice in Spain [abstract]. Blood 2006; 108: 5512

Mayordomo JI, Castellanos J, Pernas S, et al., on behalf of the ENIA Study Group. Cost analysis of febrile neutropenia management of breast cancer patients in clinical practice in Spain [abstract no. 617P]. Ann Oncol 2006; 17(Suppl. 9): ix190

Morrison VA, Wong M, Hershman D, et al. Observational study of the prevalence of febrile neutropenia in patients who received filgrastim or pegfilgrastim associated with 3–4 week chemotherapy regimens in community oncology practices. J Manag Care Pharm 2007 May; 13(4): 337–48

Sung L, Nathan PC, Alibhai SM, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of prophylactic hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors on mortality and outcomes of infection. Ann Intern Med 2007 Sep 18; 147(6): 400–11

Lyman G, Kuderer NM, Crawford J, et al. Prospective validation of a risk model for first cycle neutropenic complications in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy [abstract no. 8561]. 42nd Annual Meeting; American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2006 Jun 2–6; Atlanta (GA)

Culakova E, Wolff DA, Poniewierski MS, et al. Factors related to neutropenic events in early stage breast cancer patients [abstract no. 634]. 44th Annual Meeting; American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2008 May 30-June 3; Chicago (IL)

Pettengell R, Bosly A, Szucs TD, et al. Multivariate analysis of febrile neutropenia occurrence in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: data from the INC-EU Prospective Observational European Neutropenia Study. Br J Haematol 2009 Mar; 144(5): 677–85

Ziepert M, Schmits R, Trumper L, et al. Prognostic factors for hematotoxicity of chemotherapy in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2008 Apr; 19(4): 752–62

Acknowledgments

Drs Pettengell and Green have received honoraria and travel grants from Amgen.

The authors thank Faith Reidenbach and Supriya Srinivasan, PhD, of Scientia Medical Communications, LLC, Pleasanton, CA, USA, for writing and editorial support, which was sponsored by Amgen (Europe) GmbH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Renwick, W., Pettengell, R. & Green, M. Use of Filgrastim and Pegfilgrastim to Support Delivery of Chemotherapy. BioDrugs 23, 175–186 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200923030-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200923030-00004