Abstract

Objective: The serum profiles of isoniazid and its hydrazine metabolite were investigated in patients with tuberculosis in steady-state conditions in the hope of identifying a pharmacokinetic approach that could be useful in the clinical assessment of other patients with the same disease state.

Patients and Study Design: Isoniazid was coadministered with the other drugs included in the antitubercular regimen (rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin, morinamide). Concentrations of isoniazid and its hydrazine metabolite were measured in the collected serum samples by high performance liquid chromato-graphy. The pharmacokinetic parameters of isoniazid were estimated by WINNONLIN. Since an isoniazid serum concentration of 1.5 mg/L 3 hours after (C3) the administration of the dose (D) was demonstrated to be therapeutically efficacious with minimal neurotoxic adverse effects, the theoretical dosage adjustment (Da) required to achieve this optimal concentration in all our patients was calculated according to the inactivator index (I3) method proposed by Vivien et al. [I3 = (C3 + 0.6)/D]; [Da = 2.1/I3].

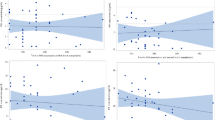

Results: A large interindividual pharmacokinetic variability was observed [especially for maximum concentration (Cmax), trough levels, area under the curve (AUC), and hydrazine metabolite production] not only according to the acetylator status as expected, but inside each group as well. The mean Da was significantly lower than the mean D in the slow acetylators (2.32 ± 0.78 vs 4.75 ± 0.47 mg/kg; p < 0.00001), while no statistically significant difference was found in the rapid acetylators (4.16 ± 3.07 vs 4.68 ± 0.81 mg/kg; p = 0.53).

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that slow acetylators show a mean daily isoniazid exposure (AUC) two-fold higher than rapid acetylators (36.42 ± 11.53 vs 16.50 ± 7.02 mg/L·h; p < 0.0001) when nearly equal isoniazid daily doses are administered (4.75 ± 0.47 vs 4.68 ± 0.81 mg/kg; p = 0.81) and no peculiar pathophysiological conditions affecting isoniazid disposition are present. It might be speculated that slow acetylators may often benefit from reduced doses (<5 mg/kg), since this strategy could either guarantee efficacy and reach the desired Cmax and C3 levels, or minimise potential toxicity risks lowering isoniazid daily exposure and fluctuations of hydrazine metabolite serum concentrations. However, care should be exercised and therapeutic drug monitoring needs to be performed in all patients, especially when peculiar pathophysiological conditions —such as malabsorption — could affect the drug’s pharmacokinetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Raviglione MC, Sudre P, Rieder HL, et al. Secular trends of tuberculosis in Western Europe. Bull World Health Organ 1993; 71: 297–306

Raviglione MC, Snider Jr DE, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. JAMA 1995; 273: 220–6

Neville K, Bromberg A, Bromberg R, et al. The third epidemic - multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Chest 1994; 105: 45–48

Peloquin CA, Berning SE. Infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 72–84

Snider Jr DE, Roper WL. The new tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 703–5

Edlin BR, Tokars JI, Grieco MH, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among hospitalized patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 1514–21

Ellner JJ, Hinman AR, Dooley SW, et al. Tuberculosis symposium: emerging problems and promise. J Infect Dis 1993; 168: 537–51

Vivien JN, Thibier R, Lepeuple A, et al. Le dosage systématique de l’isoniazide actif dans le sérum sanguin. Rev Tuberc Pneumol 1963; 27: 1103–18

Vivien JN, Thibier R, Grosset J, et al. Résultats précoces de l’isoniazido-thérapie en fonction du taux d’isoniazide actif dans le sérum. Rev Tuberc 1958; 22: 208–22

Weber WW, Hein DW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of isoniazid. Clin Pharmacokinet 1979; 4: 401–22

Holdiness MR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antituberculosis drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet 1984; 9: 511–44

Houston S, Fanning A. Current and potential treatment of tuberculosis. Drugs 1994; 48: 689–708

American Thoracic Society. Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 149: 1359–74

Lauterburg BH, Smith CV, Todd EL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of the toxic hydrazino metabolites formed from isoniazid in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1985; 235: 566–70

Dickinson DS, Bailey WC, Hirschowitz BI, et al. Risk factors for isoniazid (NIH) induced liver dysfunction. J Clin Gastro-enterol 1981; 3: 271–9

Raghupati Sarma G, Immanuel C, Kailasam S, et al. Rifampin-induced release of hydrazine from isoniazid. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 133: 1072–5

Van den Brande P, Van Steenbergen W, Vervoort G, et al. Aging and hepatotoxicity of isoniazid and rifampin in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152: 1705–8

Steele MA, Burk RF, DesPrez RM. Toxic hepatitis with isoniazid and rifampin. A meta-analysis. Chest 1991; 99:465–71

Dieu JC. Role de l’isoniazide dans l’hépatotoxicité de l’association INH-rifampicine dans le tuberculose de l’infant. J Med Lyon 1972; 53: 1323–8

Tsagaropoulo-Stinga H, Mataki-Emmanouilidou T, Karida-Kavalioti S, et al. Hepatotoxic reactions in children with severe tuberculosis treated with isoniazid-rifampin. Pediatr Infect Dis 1985; 4: 270–3

Altman C, Biour M, Grange JD. Toxicité hépatique des antituberculeux. Presse Med 1993; 22: 1212–6

Black M. Isoniazid and the liver. Am Rev Respir Dis 1974; 110: 1–3

Kucers A, Bennett NMcK. The use of antibiotics, 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1987

Ellard GA, Gammon PT. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid metabolism in man. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1976; 4: 83–113

Karlaganis G, Peretti E, Lauterburg BH. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid and acetylhydrazine in man using stable isotopes and capillary GLC-ammonia CI-MS. Experientia 1987; 43: 705

Lauterburg BH, Smith CV, Todd EL, et al. Oxidation of hydrazine metabolites formed from isoniazid. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1985; 38: 566–71

Nelson SD, Mitchell JR, Timbrell JA, et al. Isoniazid and iproniazid: activation of metabolites to toxic intermediates in man and rat. Science 1976; 193: 901–3

Woo J, Chan CHS, Walubo A, et al. Hydrazine — A possible cause of isoniazid-induced hepatic necrosis. J Med 1992; 23: 51–9

Beever IW, Blair IA, Brodie MJ. Circulating hydrazine during treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 13: 599

Gent WL, Selfart HI, Parkin DP, et al. Factors in hydrazine formation from isoniazid by paediatric and adult tuberculosis patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 43: 131–6

Donald PR, Seifart HI, Parkin DP, et al. Hydrazine production in children receiving isoniazid for the treatment of tuberculous meningitis. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 1340–3

Peloquin CA. Therapeutic drug monitoring: principles and application in Mycobacterial infections. Drug Ther 1992; 22: 31–6

Peloquin CA. Using therapeutic drug monitoring to dose the antimycobacterial drugs. Clin Chest Med 1997; 18: 79–87

Lepeuple A, Thibier R, Vivien JN, et al. Les troubles psychiques provoqués par l’isoniazide. Leur relation avec les antécédents psychiques et le taux sanguin d’isoniazide libre del malades. Rev Tuberc 1959; 23: 214–30

Canetti G, Froman S, Grosset J, et al. Mycobacteria: laboratory methods for testing drug sensitivity and resistance. Bull World Health Organ 1963; 29: 565–79

Heifets L. Qualitative and quantitative drug-susceptibility tests in mycobacteriology. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 137:1217–22

Walubo A, Chan K, Wong CL. Simultaneous assay for isoniazid and hydrazine metabolite in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in the rabbit. J Chromatogr 1991; 567: 261–6

Vivien JN, Thibier R, Lepeuple A. La pharmacocinetique de l’isoniazide dans le race blanche. Rev Fr Mal Respir 1973; 5-6: 753–72

Ellard GA. Chemotherapy of tuberculosis for patients with renal impairment. Nephron 1993; 64: 169–81

Advenier C, Saint-Aubin A, Gobert C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid in the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1980; 10: 167–9

Peloquin CA, Jaresko GS, Yong CL, et al. Population pharma-cokinetic modeling of isoniazid, rifampin and pyrazinamide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997; 41: 2670–9

Combs DL, O’Brien RJ, Geiter LJ. USPHS tuberculosis short- course chemotherapy trial 21: effectiveness, toxicity and acceptability. The report of final results. Ann Intern Med 1990; 112: 397–406

Slutkin G, Schecter GF, Hopewell PC. The results of 9-month isoniazid-rifampin therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis under program conditions in San Francisco. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138: 1622–4

Medical Sections of the American Lung Association. Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 134: 355–63

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Initial therapy for tuberculosis in the era of multidrug resistance: recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. JAMA 1993; 270: 694–8

Blair IA, MansillaTinoco R, Brodie MJ, et al. Plasma hydrazine concentrations in man after isoniazid and hydralazine administration. Hum Toxicol 1985; 4: 195–202

Peretti E, Karlaganis G, Lauterburg BH. Increased urinary excretion of toxic hydrazino metabolites of isoniazid by slow acetylators. Effect of a slow-release preparation of isoniazid. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 33: 283–6

Peretti E, Karlaganis G, Lauterburg BH. Acetylation of acetylhydrazine, the toxic metabolite of isoniazid, in humans. Inhibition by concomitant administration of isoniazid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1987; 243: 686–9

Wright JM, Timbrell JA. Factors affecting the metabolism of (14C)acetylhydrazine in rats. Drug Metab Dispos 1978; 6: 561–6

Timbrell JA, Wright JM. Studies on the effects of isoniazid on acetylhydrazine metabolism in vivo and in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos 1979; 7: 237–40

Kergueris MF, Bourin M, Larousse C. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid: influence of age. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 30: 335–40

Rey E, Pons G Crémier O, et al. Isonizid dose adjustment in a pediatric population. Ther Drug Monitor 1998; 20: 50–5

Walubo A, Chan K, Woo J, et al. The disposition of antituber-culous drugs in plasma of elderly patients. I. Isoniazid and hydrazine metabolite. Meth Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1991; 13: 545–50

Berning SE, Huitt GA, Iseman MD, et al. Malabsorption of antituberculosis medications by a patient with Aids. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1817–8

Gordon SM, Horsburgh Jr CR, Peloquin CA, et al. Low serum levels of oral antimycobacterial agents in patients with disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease. J Infect Dis 1993; 168: 1559–62

Kim YG, Shin JG, Shin SG, et al. Decreased acetylation of isoniazid in chronic renal failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993; 54: 612–20

Iseman MD, Cohn DL, Sbarbaro JA. Directly observed treatment of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 576–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pea, F., Milaneschi, R., Baraldo, M. et al. Isoniazid and its Hydrazine Metabolite in Patients with Tuberculosis. Clin. Drug Investig. 17, 145–154 (1999). https://doi.org/10.2165/00044011-199917020-00009

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00044011-199917020-00009