Abstract

Cholinesterase inhibitors are the only pharmacological class indicated for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. These drugs are also being used off label to treat severe cases of Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia and other disorders. The widespread use of cholinesterase inhibitors raises the possibility of their use in combination regimens, with the subsequent risk of deleterious drug-drug interactions in high-risk populations. The purpose of this review is to present the possible sources of pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic drug-drug interactions involving cholinesterase inhibitors.

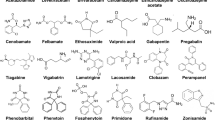

The four cholinesterase inhibitors (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine) that are currently available have different pharmacological properties that expose patients to the risk of several types of drug interactions of nonequivalent clinical relevance. The principal proven clinically relevant drug interactions involve tacrine and drugs metabolised by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2 enzyme, as well as tacrine or donepezil and antipsychotics (which results in the appearance of parkinsonian symptoms). The bioavailability of galantamine is increased by coadministration with paroxetine, ketoconazole and erythromycin. It is of interest to note that because rivastigmine is metabolised by esterases rather than CYP enzymes, unlike the other cholinesterase inhibitors, it is unlikely to be involved in pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions. Care must be taken to reduce the risk of inducing central (excitation, agitation) or peripheral (e.g. bradycardia, loss of consciousness, digestive disorders) hypercholinergic effects via drug interactions with cholinesterase inhibitors.

A review of the literature does not reveal any alarming data but does highlight the need for prudent prescription, particularly when cholinesterase inhibitors are given in combination with psychotropics or antiarrhythmics. Possible interactions involving other often coprescribed antidementia agents (e.g. memantine, antioxidants, cognitive enhancers) remain an open area requiring particularly prudent use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mayeux R, Sano M. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1670–9

Bentué-Ferrer D, Michel BF, Reymann JM, et al. Les nouveautés thérapeutiques pour la maladie d’Alzheimer. Rev Geriatr 2001;26: 511–22

Allain H, Tribut O, Reymann JM, et al. Perpectives médicamenteuses dans la maladie d’Alzheimer. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 2001; 152: 527–32

Eggert A, Crismon ML, Ereshefsky L. Alzheimer’s disease. In: Dipiro J, Talbet RL, Yee GC, et al., editors. Pharmacotherapy. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier, 1997: 1325–44

Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population of older persons: higher than previously reported. JAMA 1989; 262: 2551–6

Bachman DL, Wolf PA, Linn RT, et al. Incidence of dementia and probable Alzheimer’s disease in a general population: the Framingham Study. Neurology 1993; 43: 515–9

Sloan R. Drug interactions. In: Practical geriatric therapeutics. Oradell (NJ): Medical Economic Books, 1986: 39–50

Tribut O, Reymann JM, Polard E, et al. Interactions médicamenteuses chez le sujet âgé. Angéiologie 2000; 52: 25–38

Brawn L, Castleden C. Adverse drug reactions: an overview of special consideration in the management of the elderly patient. Drug Saf 1990; 5: 421–35

Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Tribut O, et al. Drugs and vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2003; 16: 1–6

Howard AK, Thornton AE, Altman S. Donepezil for memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol 2002; 16: 267–70

Weinstock M. Selectivity of cholinesterase inhibition: clinical implications for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 1999; 12: 307–23

Greig NH, Utsuki T, Yu Q, et al. A new therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease treatment: attention to butyrylcholinesterase. Curr Med Res Opin 2001; 17: 159–65

Poirier J. Evidence that the clinical effects of cholinesterase inhibitors are related to potency and targeting of action. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2002; 127: 6–19

Imbimbo BP. Pharmacodynamic-tolerability relationships of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 2001; 15: 375–90

Dooley M, Lamb HM. Donepezil: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2000; 16: 199–226

Spencer CM, Noble S. Rivastigmine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 1998; 13: 391–411

Scott LJ, Goa KL. Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 2000; 60: 1095–122

VanDenBerg CM, Kazmi Y, Jann MW. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2000; 16: 123–38

Nordberg A, Svensson AL. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison of tolerability and pharmacology. Drug Saf 1998; 19: 465–80

Schachter AS, Davis KL. Guidelines for the appropriate use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 1999; 11: 281–8

Summers WK. Tacrine (THA, Cognex®). J Alzheimers Dis 2000; 2: 85–93

Jann MW, Shirley KL, Small GW. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002; 41: 719–39

Grutzendler J, Morris JC. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 2001; 61: 41–52

Polinsky RJ. Clinical pharmacology of rivastigmine: a newgeneration acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Ther 1998; 20: 634–47

Maelicke A, Samochocki M, Jostock R, et al. Allosteric sensitization of nicotinic receptors by galantamine, a new treatment strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49: 279–88

Ormrod D, Spencer C. Metrifonate: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 2000; 13: 443–67

Schmidt BH, Heinig R. The pharmacological basis for metrifonate’s favourable tolerability in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1998; 9 Suppl. 2: 15–9

Farlow MR, Cyrus PA. Metrifonate therapy in Alzheimer’s disease: a pooled analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000; 11: 202–11

Clinical trials with metrifonate have been stopped by Bayer. Reactions 1998 Nov 14; 1(727): 4

Sramek JJ, Cutler NR. Recent developments in the drug treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 1999; 14: 359–73

Bai DL, Tang XC, He XC. Huperzine A: a potential therapeutic agent for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Med Chem 2000; 7: 355–74

Gauthier S. Cholinergic adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology and management. Drugs Aging 2001; 18: 853–62

Inglis F. The tolerability and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2002; 127: 45–63

Bénéton C, Bentué-Ferrer D, Reymann JM. Les interactions médicamenteuses. Angéiologie 1997; 49: 67–78

Sadowski DC. Drug interactions with antacids: mechanisms and clinical significance. Drug Saf 1994; 11: 395–707

Neuvonen PJ, Kivisto KT. Enhancement of drug absorption by antacids: an unrecognised drug interaction. Clin Pharmacokinet 1994; 27: 120–8

Heinig R, Boettcher M, Herman-Gnjidic Z, et al. Effects of a magnesium/aluminium hydroxide-containing antacid, cimetidine or ranitidine on the pharmacokinetics of metrifonate and its metabolite DDVP. Clin Drug Invest 1999; 17: 67–77

Huang F, Lasseter KC, Janssens L, et al. Pharmacokinetic and safety assessments of galantamine and risperidone after the two drugs are administered alone and together. J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 42: 1341–51

Janssen. Reminyl tablets: prescribing information. Turnhoutseweg: Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, 2000 Jul 11

Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K. Food-drug interactions. Drugs 2002; 62: 1481–502

Welty DF, Siedlik PH, Posvar EL, et al. The temporal effect offood on tacrine bioavailability. J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 34: 985–8

Anand R, Gharabawi G, Enz A. Efficacy and safety results of the early phase studies with Exelon™ (ENA 713) in Alzheimer’s disease: an overview. J Drug Dev Clin Pract 1996; 8: 109–16

Wrighton SA, VandenBranden M, Ring BJ. The human drug metabolizing cytochromes P450. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1996; 24: 461–73

Meyer UA. Overview of enzymes of drug metabolism. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1996; 24: 449–59

Fontana RJ, deVries TM, Woolf TF, et al. Caffeine based measures of CYP1A2 activity correlate with oral clearance of tacrine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46: 221–8

Becquemont L, Ragueneau I, Le Bot MA, et al. Influence of the CYP1A2 inhibitor fluvoxamine on tacrine pharmacokinetics in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1997; 61: 619–27

Larsen JT, Hansen LL, Spigset O, et al. Fluvoxamine is a potent inhibitor of tacrine metabolism in vivo. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 55: 375–82

Forgue ST, Reece PA, Sedman AJ, et al. Inhibition of tacrineoral clearance by cimetidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 59: 444–9

Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and cimetidine: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following single and multiple doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46 Suppl. 1: 25–9

Reece PA, Garnett WR, Rock WL, et al. Lack of effect of tacrine administration on the anticoagulant activity of warfarin. J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 35: 526–8

Laine K, Palovaara S, Tapanainen P, et al. Plasma tacrine concentrations are significantly increased by concomitant hormone replacement therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999; 66: 602–8

Welty D, Pool W, Woolf T, et al. The effect of smoking on the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of Cognex in healthy volunteers [abstract]. Pharm Res 1993; 10Suppl. 10: S334

Zevin S, Benowitz NL. Drug interactions with tobacco smoking: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet 1999; 36: 425–38

Schein JR. Cigarette smoking and clinically significant drug interactions. Ann Pharmacother 1995; 29: 1139–48

Crismon ML. Tacrine: first drug approved for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 744–51

Parke-Davis. Cognex (tacrine hydrochloride): prescribing information. Morris Plains (NJ): Parke-Davis, 1993

Tiseo PJ, Foley K, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and theophylline: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following multiple-dose administration in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46 Suppl. 1: 35–9

Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and ketoconazole: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following single and multiple doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46 Suppl. 1: 30–4

Carrier L. Donepezil and paroxetine: possible drug interaction [letter]. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47: 1037

Tiseo PJ, Foley K, Friedhoff LT. The effect of multiple doses of donepezil HCl on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46 Suppl. 1: 45–50

Heinig R, Kitchin N, Rolan P. Disposition of a single dose of warfarin in healthy individuals after pretreatment with metrifonate. Clin Drug Invest 1999; 18: 151–9

Carcenac D, Martin-Hunvadi C, Kiesmann M, et al. Extrapyramidal syndrome induced by donepezil. Presse Med 2000; 29: 992–3

Ott BR, Lannon MC. Exacerbation of parkinsonism by tacrine. Clin Neuropharmacol 1992; 15: 322–5

Bourke D, Druckenbrod RW. Possible association between donepezil and worsening Parkinson’s disease. Ann Pharmacother 1998; 32: 610–1

McSwain ML, Forman LM. Severe parkinsonian symptom development on combination treatment with tacrine and halo-peridol [letter]. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15: 284

Maany I. Adverse interaction of tacrine and haloperidol [letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 1504

Arai M. Parkinsonism onset in a patient concurrently using tiapride and donepezil. Intern Med 2000; 39: 863

Magnuson TM, Keller BK, Burke WJ. Extrapyramidal side effects in a patient treated with risperidone plus donepezil. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1458–9

Weiser M, Rotmensch HH, Korczyn AD, et al. A pilot, randomized, open-label trial assessing safety and pharmacokinetic parameters of co-administration of rivastigmine with risperidone in dementia patients with behavioral disturbances. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17: 343–6

Madhusoodanan S, Brenner R, Cohen CI. Role of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of psychosis and agitation associated with dementia. CNS Drugs 1999; 12: 135–50

Edell WS, Tunis SL. Antipsychotic treatment of behavioral and sychological symptoms of dementia in geropsychiatric inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9: 289–97

Reynolds PL, Strayer SM. Neuroleptics for behavioral symptoms f dementia. J Fam Pract 2000; 49: 78–9

Company core data sheet. Paris: le Dictionnaire Vidal® édition, 2003

Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Lieury A, et al. Beta-blockers and memory. BVS Europe 1996; 3: 5–14

Tiseo PJ, Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT. Co-administration of donepezil and digoxin produces no pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interactions [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1997; 7Suppl. 2: S252

Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and digoxin: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes. Br J Pharmacol 1998; 46 Suppl. 1: 40–4

Polard E, Belliard S, Duclos R, et al. Malaise ou perte de connaissance et inhibiteurs de l’acétylcholinesterase. Therapie. In press

Lane G. Potential donepezil: succinylcholine interaction [letter]. an J Hosp Pharm 1998; 51: 272

Heath ML. Donepezil, Alzheimer’s disease and suxamethonium [letter]. Anaesthesia 1997; 52: 1018

Sprung J, Castellani WJ, Srinivasan V, et al. The effects of donepezil and neostigmine in a patient with unusual pseudocholinesterase activity. Anesth Analg 1998; 87: 1203–5

Morillo J, Demartini Ferrari A, Roca de Togores Lopez A. Interaction of donepezil and muscular blockers in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2003; 50: 97–100

Heath ML. Donepezil and succinylcholine [letter]. Anaesthesia 2003; 58: 202

Piecoro LT, Wermeling DP, Schmitt FA, et al. Seizures in atients receiving concomitant antimuscarinics and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18: 1129–32

Crismon ML. Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of cholinesterase inhibitors administered in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18 (2 Pt 2): 47S–54S

Hooten WM, Pearlson G. Delirium caused by tacrine and ibuprofen nteraction [letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 842

Benveniste EN, Nguyen VT, O’Keefe GM. Immunological aspects of microglia: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 2001; 39: 381–91

Verrico MM, Nace DA, Towers AL. Fulminant chemical hepatitis possibly associated with donepezil and sertraline therapy. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1659–63

Grossberg GT, Stahelin HB, Messina JC. Lack of adverse pharmacodynamic drug interactions with rivastigmine and twenty-two classes of medications. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2000; 15: 242–7

Schiick S, Bentué-Ferrer D, Beaufils C, et al. Effets indésirables et médicaments de la maladie d’Alzheimer. Thérapie 1999; 54: 237–42

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Gerald Pope for his help with the English translation.

Preparation of this manuscript was done as a university activity, without any source of supplementary funding. The authors certify not to have conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this review, but Prof. H. Allain declares that he is a regular invited speaker by Janssen-Cilag, for which he receives honoraria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bentué-Ferrer, D., Tribut, O., Polard, E. et al. Clinically Significant Drug Interactions with Cholinesterase Inhibitors. CNS Drugs 17, 947–963 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200317130-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200317130-00002