Abstract

Summary

Synopsis

The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) has confirmed the link between the cholesterol-reducing effects of simvastatin and improved survival in patients with hypercholesterolaemia and pre-existing coronary heart disease (CHD). Pharmacoeconomic analyses of the 4S trial. using prospectively col/ected data for cost-generating events. demonstrate that the cost per year of life saved for simvastatin in such patients falls within the range considered cost effective. Reductions in resource utilisation costs (numbers ofhospitalisations and revascularisation procedures) largely offset the acquisition cost of long term simvastatin treatment in the US.

Models of primary prevention incorporating epidemiological data to predict CHD events generally suffer from deficiencies in the methods and assumptions used. and no firm conclusions can be made at present regarding relative cost effectiveness of the drugs studied. including simvastatin. It is generally agreed that cost effectiveness will improve in patients with higher absolute risk of CHD.

In summary. simvastatin has been shown in a major clinical trial and its companion economic analyses to reduce mortality and to be cost effective in patients with hypercholesterolaemia and existing CHD. As is the case for others of its class. its cost-effectiveness ratio in primary prevention remains to be ascertained. This issue aside. simvastatin is a rational choice of cholesterol-lowering agent in secondary prevention whose use can be justified on an economic basis.

Economic Implications of Dysllpldaemla and Coronary Heart Disease

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the major cause of death in industrialised nations. Treatment of cardiovascular diseases consumes about 10 to 15% of total healthcare budgets in OECD countries. Annual costs in the US alone approach $US 100 bilIion for treatment and lost wages. Dyslipidaemia is one of several established risk factors for CHD: a 10% reduction in serum cholesterol levels is linked to a decrease of 15 to 20% in the 2-year incidence of CHD. Furthermore, the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) using simvastatin as secondary prevention has established that reducing cholesterol levels improves survival.

Costs of treating dyslipidaemia include those related to initial screening, which vary considerably depending on whether programmes are comprehensive or selective, and ensuing treatment (dietary consultations, physician visits, nursing time, laboratory tests and drug acquisition). For an intervention programme in the UK, it was calculated that lipid-measuring accounted for 7%, dietary counselIing 3% and drug therapy 89% of total costs. As a rule, the cost effectiveness of intervention increases with increasing risk. The incremental cost effectiveness of various interventions has not been measured extensively. In the UK, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for therapy with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors versus diet was estimated to be £ 13 500/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Factors Influencing Phamacoeconomic Analyses of Slmvastatin

In the 4S trial, simvastatin therapy decreased total mortality by 30% and coronary mortality by 42%, and reduced the incidence of cost-generating CHD event~ over a 5.4-year period (see Pharmacoeconomic Assessments summary). Clinical benefit was greatest in men aged <60 years, but gains were also obtained in women and the elderly.

Serum cholesterol reduction is a surrogate end-point which nonetheless has been extensively incorporated into economic analyses. The effects of simvastatin on lipids and lipoproteins are well established. Serum levels of total cholesterol are reduced by about 20 to 40%, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by 35 to 45% and triglycerides by 10 to 20%; high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterollevels rise by 5 to 15%. Simvastatin is effective in patients with dyslipidaemia and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and does not worsen glucose control or renal function.

Simvastatin reduces total and LDL cholesterol levels to a greater extent than bile acid sequestrants or fibrates. whereas fibrates more effectively increase HDL cholesterol and lower triglyceride levels. Compared with other HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. simvastatin 10 mg/day is therapeutically equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/day. pravastatin 20 mg/day and tluvastatin 40 or 80 mg/day. Like other HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. simvastatin is well tolerated and is rarely associated with serious adverse events. The cost of adverse events is unlikely to be significant but has been incorporated into some economic analyses of simvastatin.

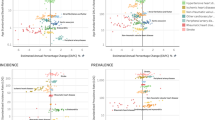

Pharmacoeconomic Assessments

Simvastatin provides clinical benefits and is cost effective in secondary prevention. as evidenced by findings of the 4S trial. A cost analysis of the 4S trial used prospectively collected data on cost-generating events to demonstrate that. compared with placebo. simvastatin produces significant reductions in the number of hospitalisations for acute cardiovascular disease (by 26%), CHD events (32%), revascularisation procedures (32%) and days spent in hospital for these events (34%). Applying diagnosis-related group (DRG) costs in the US yielded a 31 % saving in the cost of these events over 5.4 years, reducing the discounted acquisition costs of simvastatin treatment by 88%.

Using Swedish cost data and the 4S trial results, a subsequent costeffectiveness analysis estimated a 32% saving in total cost of hospitalisations which translated into an incremental cost per year of life saved (YLS) of SEK56 400 (= £ 5502) for simvastatin. assuming a discounted gain of 0.24 lifeyears. This figure is well below the cut-off point for interventions deemed cost effective in Sweden (SEKIOO 0(0) and was robust to varying assumptions regarding life expectancy. costs of treatment and discount rates for costs and benefits. The cost-effectiveness ratio ranged from £ 4137 to £ 8824/YLS after conversion of these data to pounds sterling using DRG weights for costs in 10 other countries. These cost-effectiveness data are. however, valid only if extrapolated to countries with healthcare systems comparable to those in the Scandinavian countries studied. and in patients similar to those in the 4S trial.

Investigators of simvastatin economics in the setting of primary prevention have attempted to compensate for a lack of clinical trial data regarding CHD events by extrapolating epidemiological and observational study results. Simvastatin consistently proved more cost effective than cholestyramine in these models of primary prevention. Present data. however. do not permit firm conclusions regarding relative cost effectiveness among HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. particularly as acquisition costs will vary across markets. The same cautionary note applies to results of simple cost-effectiveness analyses using cholesterol reduction as a surrogate clinical end-point and drug acquisition costs in various countries to determine relative cost effectiveness among HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, particularly as acquisition costs will vary across markets.

The same cautionary note applies to results of simple cost-effectiveness analyses using cholesterol reduction as a surrogate clinical end-point and drug acquisition costs in various countries to determine relative cost effectiveness among HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chrisp P, Lewis NJW, Milne RJ. Simvastatin: a pharmacoeconomic evaluation of its cost-effectiveness in hypercholesterolaemia and prevention of coronary heart disease. PharmacoEconomics 1992 Feb; 1: 124–45

Reckless JPD. The economics of choleslerol lowering. Baillieres elin Endocrin Melab 1990; 4 (4): 947–72

Scoll WG, While HD, Scoll HM. Cost of coronary heart disease in New Zealand. N Z Med J 1993 Aug 25; 106 (962): 347–9

Reckless JPD. Cost-effecliveness of hypolipidaemic drugs. Postgrad Med J 1993; 69 Suppl.1: S30–3

Simvaslalin cost-effective in secondary prevention. Scrip 1995 Apr 4; 2013–30

Johannesson M, Borgquisl L, Nilsson-Ehle P, et al. The cost of screening for hypercholeslerolaemia — resulls from a clinicaltrial in Swedish primary heallh care. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1993 Nov; 53: 725–32

National Cholesterol Education Program. Second Report of the Experl Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Choleslerol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 1994 Mar; 89: 1336–445

Office of Health Economics. Coronary heart disease. The need for action. Statement from the Office of Health Economics. London, 1990: 15–18

Field K, Thorogood M, Silagy C, et al. Strategies for reducing coronary risk factors in primary care: which is most cost effective? BMJ 1995 Apr 29; 310: 1109–12

Ramsay LE, Haq IU, Jackson PR, et al. Targeling lipidlowering drug Iherapy for primary prevenlion of coronary disease: an updaled Sheffied lable. Lancet 1996 Aug 10; 348: 387–8

Kuntz KM, Lee TH. Cost-effectiveness of accepted measures for intervention in coronary heart disease. Coron Arlery Dis 1995; 6 (6): 472–8

Okayama A, Ueshima H, Marmol MG, et al. Changes in lolal serum choleslerol and olher risk faclors for cardiovascular disease in Japan, 1980-1989. Int J Epidemiol 1993 Dec; 22: 1038–47

Blake GH, Triplett LC. Managemenl of hypercholeslerolemia. Am Fam Physician 1995 Apr; 51: 1157–66

Tomson Y, Johannesson M, Aberg H. The costs and effects of TWO different lipid intervention programmes in primary health care. J Intern Med 1995 Jan; 237: 13–7

Nealon JD, Blackburn H, Jacobs D, et al. Serum choleslerol level and mortality findings for men screened in the Multiple Risk Faclor Intervention Trial. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152: 1490–500

Flelcher AE, Bulpill CJ. Pharmacoeconomic evalUalion of risk faclors for cardiovascular disease. An epidemiological perspeclive. PharmacoEconomics 1992 Jan; 1: 33–44

Holme I. Choleslerol redUClion and ils impact on coronary artery disease and lolal morlalily. Am J Cardiol 1995 Sep 28; 76: 10–7

Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Carinci F, et al. Mela-analysis, clinical trials, and transferability of research results inlo practice: the case of choleslerol-lowering interventions in the secondary prevenlion of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 1996 Jun 10; 156: 1158–72

O’Brien BJ. Cholesterol and coronary heart disease: consensus or controversy? 8Questions of cost-effectiveness. London: From the Office of Health Economics 1991: 78–100

Grover SA, Coupal L, Fahkry R, et al. Screening for hypercholesterolemia among Canadians: how much will it cost? Can Med Assoc J 1991; 144 (2): 161–8

Lindholm L, Rosen M, Weinehall L, et al. Cost effectiveness and equity of a community hased cardiovascular disease prevention programme in Norsjo, Sweden. J Epidemiol Communily Health 1996; 50: 190–5

Reckless JPD. Cost-effecliveness of clinical care for hyperlipidaemia. In: Lewis B, Assmann G, editors. The social and economic contexts of coronary prevention. London: Current Medical Lilerature, 1990: 94–104

McGehee MM, Johnson EQ, Rasmussen HM, et al. Benefits and cosls of medical nutrition therapy by registered dietitians for patients with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Diet Assoc 1995; 95: 1041–3

Kinlay S, O’Connell D, Evans D, et al. A new method of estimating cost effectiveness of choleslerol reduction therapy for prevention of heart disease. PharmacoEconomics 1994 Mar; 5: 238–48

Davey Smith G, Song F, Sheldon TA. Choleslerol lowering and mortality: the importance of considering initial level of risk. BMJ 1993 May 22; 306: 1367–73

LaRosa JC. Cholesterol lowering, low cholesterol, and mortality. Am J Cardiol 1993 Oct 1; 72: 776–86

Wonderling D, McDermoll C, Buxlon M, et al. Costs and cost effectiveness of cardiovascular screening and intervention: the British family heart study. BMJ 1996; 312: 1269–73

Langham S, Thorogood M, Normand C, et al. Cosls and cost effecliveness of heallh checks conducled by nurses in primary care: Ihe Oxcheck sludy. BMJ 1996 May 18; 312: 1265–8

Wonderling D, Langham S, Buxlon M, et al. Wha can be concluded from Ihe Oxcheck and British family heart studies: commentary on cost effectiveness analyses. BMJ 1996 May 18; 312: 1274–8

Ploskcr GL, McTavish D. Simvastatin: a reappraisal of ils pharmacology and therapeulic efficacy in hypercholesterolaemia. Drugs 1995 Aug; 50: 334–63

Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Study Group. Randomised Irial of choleslerol lowering in 4444 palienls wilh coronary heart disease: Ihe Scandinavian Simvastalin Sun ivai Slud) (4S). Lancet 1994 Nov 19; 344: 1383–9

Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Berg K, et al. Choleslerol lowering and Ihe use of heallhcare resources: resulls of the Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Sludy. Circulation 1996 May 15; 95: 1796–802

Geurian KL. The choleslerol conlroversy. Ann Pharmacolher 1996; 30: 495–500

Hippisley-Cox J. Lowering patients’ choleslerol: eXlrapolaling resulls of Irial of simvaslalin gives room for doubl [letter]. BMJ 1995 Sep 9; 311: 690–1

Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR. for Ihe Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Study Group. Reducing Ihe risk of coronary evenls: evidence from the Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Study (4S). Am J Cardiol 1995 Sep 28; 76: 64C–8C

Tuomilehlo J, Guimaraes AC, Kellner H, et al. Dose-response of simvaslalin in primary hypercholeslerolemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1994 Dec; 24: 941–9

Keech A, Collins R, MacMahon S, et al. Three-year followup of Ihe Oxford Choleslerol Sludy: assessment of Ihe efficacy and safely of simvaslalin in preparalion for a large morIa lily sludy. Eur Heart J 1994 Feb; 15: 255–69

Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Sludy Group. Baseline serum choleslerol and Irealmenl effecI in Ihe Scandinavian Simvaslalin Survival Sludy Group. Lancet 1995 May 20; 345: 1274–5

Lansberg PJ, Mitchel YB, Shapiro D, et al. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of simvastatin in a large cohort of elderly hypercholesterolemic patients. Atherosclerosis 1995 Aug; 116: 153–62

Quiney J, Watts GF, Kerr-Muir M, et al. One year experience ill the treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia with simvastatin. Postgrad Med J 1992 Jul; 68: 575–80

Knops RE, Kroon AA, Mol MJTM, et al. Long-term experience (6 years) with simvastatin in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Neth J Med 1995 Apr; 46: 171–8

Kazumi T, Yoshino G, Ohki A, et al. Long-term effects of simvastatin in hypercholesterolemic patients with NIDDM and additional atherosclerotic risk factors. Horm Metab Res 1995 May; 27: 239–43

Farrer M, Winocour PH, Evans K, et al. Simvastatin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: effect on serum lipids, lipoproteins and haemostatic measures. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1994 Mar; 23: 111–9

Miccoli R, Bertolotto A, Giovannini MG, et al. Simvastatin for lowering cholesterol levels in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and in primary hypercholesterolemia. Curr Ther Res 1992 Jan; 51: 66–74

Sartor G, Katzman P, Eizyk E, et al. Simvastatin treatment of, hypercholesterolemia in patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995 Jan; 33: 3–6

Martini S, Gabelli C, Pagano GF, et al. Efficacy and safety of simvastatin for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in patients with and without type II diabetes. Curr Ther Res 1992 Aug; 52: 281–90

Nielsen S, Schmitz O, Moller N, et al. Renal function and insulin sensitivity during simvastatin treatment in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Diabetologia 1993 Oct; 36: 1079–86

Hsu I, Spinler SA, Johnson NE. Comparative evaluation of the safety and efficacy of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor monotherapy in the treatment of primary hypercholesterolemia. Ann Pharmacother 1995 Jul-Aug; 29: 743–59

Farmer JA, Washington LC, Jones PH, et al. Comparative effects of simvastatin and lovastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Clin Ther 1992 Sep-Oct; 14: 708–17

Illingworth DR, Tobert JA. A review of clinical trials comparing HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Clin Ther 1994 May-Jun; 16 (3): 366–85

Illingworth DR, Bacon S, Pappu AS, et al. Comparative hypolipidemic effects of lovastatin and simvastatin in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 1992 Sep; 96: 53–64

Douste-Blazy P, Ribeiro VG, Seed M, et al. Comparative study of the efficacy and tolerability of simvastatin and pravastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia. Drug Invest 1993 Dec; 6: 353–61

Plosker GL, Wagstaff AJ. Fluvastatin: a review of its pharmacology and use in the management of hypercholesterolaemia. Drugs 1996 Mar; 51 (3): 433–59

Malini PL, de Divitiis O, di Somma S, et al. A comparative study of simvastatin versus pravastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis 1992 Dec; 97 Suppl.: S41–7

Linton CJ, Scott RS, Sutherland WHF, et al. Treating hypercholesterolaemia with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors: a direct comparison of simvastatin and pravastatin. Aust N Z J Med 1993 Aug; 23: 381–6

Simvastatin Pravastatin Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of simvastatin and pravastatin for hypercholesterolaemia. Am J Cardiol 1993 Jun 15; 71: 1408–14

Boccuzzi SJ, Keegan ME, Hirsch LJ, et al. Long term experience with simvastatin. Drug Invest 1993; 5 (2): 135–40

Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Pyoralii K, et al. Safety and tolerability of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin over 5 years in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) [abstract]. Presented at the 66th Congress of the European Atherosclerosis Society, Florence, 1996 Jul 13-17: 223

Zureik M, Courbon D, Ducimetiere P. Serum cholesterol concentration and death from suicide in men: Paris prospective study I. BMJ 1996 Sep 14; 313: 649–51

Jungnickel PW. Cholesterol-lowering therapy: is there really a controversy? Ann Pharmacother 1996 May; 30: 539–42

Wardle J, Armitage J, Collins R, et al. Randomised placebo controlled trial of effect on mood of lowering cholesterol concentration. BMJ 1996 Jul 13; 313: 75–8

Drummond MF, Heyse J, Cook J. Selection of end points in economic evaluations of coronary-heart-disease interventions. Med Decis Making 1993 Jul-Sep; 13: 184–90

Goldman L, Garber AM, Grover SA, et al. Task force 6. Cost effectiveness of assessment and management of risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996 Apr; 27: 1020–30

Jonsson B, Johannesson M, Kjekshus J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cholesterol lowering. Results from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 1001–7

Reckless JPD. The 4S study and its pharmacoeconomic implications. PharmacoEconomics 1996 Feb; 9: 101–5

Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford J. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolaemia. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1301–7

Glick H, Heyse JF, Thompson D, et al. A model for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering treatment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1992 Fall; 8: 719–34

Martens LL, Rutten FFH, Erkelens DW, et al. Cost effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapy in The Netherlands: simvastatin versus cholestyramine. Am J Med 1989; 87 Suppl.4A: 54S–8S

Martens LL, Rutten FFH, Erkelens DW, et al. Clinical benefits and cost-effectivness of lowering serum cholesterol levels: the case of simvastatin and cholestyramine in The Netherlands. Am J Cardiol 1990; 65: 27F–32F

Hjalte K, Lindgren B, Persson U. Cost-effectiveness of simvastatin versus cholestyramine. Results for Sweden. PharmacoEconomics 1992 Mar; 1: 213–6

Martens LL, Guibert R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lipid modifying therapy in Canada: comparison of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Clin Ther 1994 Nov-Dec; 16: 1052–62

Martens LL. Cost effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin in the Netherlands [abstract]. Drug Info J 1994 Apr-Jun; 28: 437–8

Martens LL, Rutten FFH, Kuijpens JLP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lowering serum cholesterol levels by simvastatin and cholestyramine [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1991; 135 (15): 655–9

Hamillon VH, Racicol F-E, Zowall H, et al. The costeffectiveness of HMG-CoA reductase inhihitors to prevent coronary heart disease: estimating the benefits of increasing HDL e. JAMA 1995 Apr 5; 273: 1032–8

Jolain B, Pettitt D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lipid-modifying therapy in Canada: comparison of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in the primary prevenlion of coronary heart disease [letter]. Clin Ther 1995 May-Jun; 17: 572–5

Guibert R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of lipid-modifying therapy in Canada: comparison of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Reply [letter]. Clin Ther 1995 May-Jun; 17: 575–80

Garnell WR. Fluvastatin cost considerations [letter]. Ann Pharmacother 1994 Sep; 28: 1111–2

Lim MCL, Foo WM. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of simvastatin and gemfibrozil in the treatment of hyperlipidaemia. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1992 Jan; 21: 34–7

Smart AJ, Walters L. Pharmaco-economic assessment of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. S Afr Med J 1994 Dec; 84: 834–7

Sprecher DL, Jokubaitis L. Cost-effectiveness of combined statin-resin therapy. Reply [letter]. Ann Intern Med 1994 Oct 1; 121: 548–9

Blum CB. Comparison of properties of four inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. Am J Cardiol 1994 May 26; 73: 3D–11D

Neil HAW, Roe L, Godlee RJP, et al. Randomised trial of lipid lowering dietary advice in general practice: the effects on serum lipids, lipoproteins and antioxidants. BMJ 1996; 310: 569–73

Denke MA. Cholesterol-lowering diets. A review of the evidence. Arch Intern Med 1995 Jan 9; 155: 17–26

Caggiula AW, Watson JE, Kuller LH, et al. Cholesterol lowering intervention program: effect of the Step 1 diet in community office practices. Arch Intern Med 1996 Jun 10; 156: 1205–13

Pyoralia K, De Backer G, Graham I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology. European Atherosclerosis Sociely and European Society of Hypertension. Atherosclerosis 1994; 110: 121–61

Betteridge DJ, Dodson PM, Durrington PN, et al. Management of hyperlipidaemia: guidelines of the British Hyperlipidaemia Association. Postgrad Med J 1993; 69: 359–69

LaRosa JC. Cholesterol agonistics. Ann Intern Med 1996 Mar 1; 124: 505–8

New cholesterol screening guidelines ‘miss the boat’. Pharmacoecon Outcomes News 1996 Mar 16; 53: 2

American College of Physicians. Guidelines for using serum cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels as screening tests for preventing coronary heart disease in adults. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124: 515–7

Garher AM, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Cholesterol screening in asymptomatic adults, revisited. Ann Intern Med 1996 Mar 1; 124: 518–31

Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). JAMA 1993 Jun 16; 269: 3015–23

ACP cholesterol screening guidelines are ‘likely to confuse’. FDC Rep Pink Sheet 1996 Mar 4: T&G 12

FDA approves Zocor label change. Marketletter 1995 (10 Jul): 23

Additional simvastatin indications. Inpharma 1995 Oct 14; 1008: 22

Canadas Health Protection Branch has approved Merck Frosst Canadas Zocor. Markctletter 1996 May 20; 23: 28

Lipid-lowering agents: where is the evidence of increased survival? WHO Drug Info 1994; 8 (4): 204–6

Yusuf S, Anand S. Cost of prevention. The case of lipid lowering. Circulation 1996; 93: 1774–6

Aursnes I, Thorvik E, Forsen L, et al. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness ratio of cholesterol-lowering drugs in secondary prevention of myocardial infarction [abstract]. The 3rd International Symposium on Multiple Risk Factors in Cardiovascular Disease Vascular and Organ Protection: 1994 Jul 6-9; Florence, 26.

Goldman L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition for primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1991; 265 (9): 1145–51

Ashraf T, Hay JW, Crouse JR, et al. The cost-effectiveness of pravastatin in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1995; 78: 409–14

Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996 Oct 3; 335 (14): 1001–9

LaRosa JC. Cholesterol-lowering and the cost-effective prevention of recurrent coronary disease. CVR&R 1996 Aug: 10–28

ASPIRE Steering Group. A British Cardiac Society survey of the potential for the secondary prevention of coronary disease. ASPIRE (Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events). Principal results. Heart 1996; 75: 334–42

Zocor gains life-saving indication in US. Scrip 1995 Jul 14; 2042: 16

Shepherd J, Prall M. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clnical practice: a commentary on current treatment patterns in six European countries in relation to published recommendations. Cardiology 1996; 87: 1–5

Marcelino JJ, Feingold KR. Inadequate treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors by health care providers. Am J Med 1996; 100: 605–10

Jackson R, Beaglehole R. Evidence-based management of dy, lipidaemia. Lancet 1995 Dec 2; 346: 1440–2

Dyslipidaemia Advisory Group on hehalf of the National Heart Foundation of New Zealand. 1996 National Heart Foundation clinical guidelines for the assessment and management of dyslipidaemia. N Z Med J 1996; 109: 224–32

Kaplan NM. Lipid intervention trials in primary prevention: a critical review. Clin Exp Hypertens 1992 A14(122): 109–18

Pharoah PDP, Hollingworth W. Cost effectiveness of lowering cholesterol concintration with stalins in patients with and without pre-existing coronary heart disease: life table method applied to health authority population. BMJ 1996 Jun 8; 312: 1443–8

Haq IU, Jackson PR, Yeo WW, et al. Lipid-lowering for primary prevention of coronary disease: what policy now? [abstract]. The 66th Congress of the European Atherosclerosis Society: 1996, Jul 13-17; Aorence, 103

Malik IS, Anderson MH. Cost-efficacy of cholesterol lowering: West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study versus the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study [abstract]. Heart 1996 May; 75 Suppl.1: 77

Hyperlipidaemia: new evidence about treatment. Me Re C Bull 1996 April; 7 (4): 13–6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: I. Aursnes, Department of Phannacotherapeutics, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; G. Davey Smith, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, England; R. Guibert, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; B. Jönsson, Stockholm School of Economics, Centre for Health Economics, Stockholm, Sweden; S. Kinlay, Department of Medicine, Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; M. Nakamura, Department of Epidemiology and Mass Examination for Cardiovascular Disease, The Center for Adult Diseases, Osaka, Japan; A. Okayama, Department of Health Science, Shiga University of Medical Science, Ohtsu, Japan; M.F. Oliver, Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine at the National Heart & Lung Institute, London, England; J.P.D. Reckless, Royal United Hospital, Bath, England.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goa, K.L., Barradell, L.B. & McTavish, D. Simvastatin. Pharmacoeconomics 11, 89–110 (1997). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199711010-00010

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199711010-00010