Abstract

The field of metallic glasses has been an active area of research owing to the complex structure–property correlations and intricacies surrounding glass formation and relaxation. This review provides a thorough examination of significant works that elucidate the structure–property correlations of metallic glasses, derived from detailed atomistic simulations coupled with data-driven approaches. The review starts with the theoretical and fundamental framework for understanding important properties of metallic glasses such as transition temperatures, relaxation phenomena, the potential energy landscape, structural features such as soft spots and shear transformation zones, atomic stiffness and structural correlations. The need to understand these concepts for leveraging metallic glasses for a wide range of applications such as performance under tensile loading, viscoelastic properties, relaxation behavior and shock loading is also elucidated. Finally, the use of machine learning algorithms in predicting the properties of metallic glasses along with their applications, limitations and scope for future work is presented.

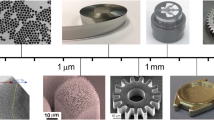

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metallic glasses (MGs) are solid alloys widely recognized for their disordered and amorphous structure, achieved through rapid cooling of metallic liquids with glass-forming properties. Their atomic arrangement typically lacks long-range periodicity, comprising single or multiple phases. In contrast to crystalline metals, MGs exhibit significantly enhanced mechanical properties due to the absence of discontinuities such as grain boundaries, dislocations, and segregation, which are commonly found in their crystalline counterparts. Hence, the correlation between structure and property emerges as a compelling challenge in glassy physics, necessitating careful optimization of diverse compositional and processing parameters to finely tune MGs for specific applications [1].

The initial successful development of MG was achieved with the \(Au_{75}Si_{25}\) alloy by Klement et al. in 1960 using the gas-phase deposition technique [2]. Over the past six decades, numerous studies have been conducted to develop and understand novel families of MGs, encompassing a wide range of metallic elements found in the periodic table [3, 4]. These MGs can be categorized into the following two groups: either the metal-metal glasses (magnesium, zinc, calcium, aluminum, copper, titanium, lanthanum, and cerium) or the metal-metalloid glasses, \(M_{1-x}N_{x}\), where x represents the content of metalloid in the glass. It contains combinations of transition metal elements like iron, copper, nickel, lead, gold, and platinum, and metallic compounds like phosphorus, boron, silicon or carbon [5]. In their research, Inoue [6] outlined the generic criteria for the development of amorphous alloys, considering the atomic-level structure, local topological and chemical ordering, as well as the nature of bonding. Takeuchi and Inoue [7] further refined this classification, particularly for multicomponent systems with more than three elements, atomic size mismatch above \(12\%\), negative heat of mixing and compositions of alloys that are comparable to deep eutectics [6]. According to the three-component rule, glassy alloy structures are observed to exhibit short-range icosahedral atomic configurations [8]. This rule stems from the fact that icosahedral structures exhibit dense local packing that are intrinsically incompatible with crystalline formation, thereby hindering the formation of long-range ordering. This hypothesis was initially proposed by Frank [9], with the first experimental validation presented by Kelton [10].

In contrast to well-known glass systems such as silicates, metals tend to crystallize readily during solidification, posing challenges for the formation of MGs. Hence, the thermodynamics and kinetics governing the formation of supercooled liquid play a pivotal role in elucidating the glass-forming ability (GFA), which varies across different alloys. In their comprehensive work, Inoue et al. [11] investigated the GFA and optimal cooling rate required for efficient metallic alloy glass formation. It is now widely recognized that the degree of supercooling significantly influences MG formation and can be effectively tailored through ideal selection of the alloy constituents [12].

Turnbull suggested that a liquid could be more easily undercooled and form a glass at relatively lower cooling rates if a ratio known as the reduced glass transition temperature, \(T_{\text{rg}} = {T_g}/{T_m}\), was approximately 2/3 or higher. Here, \(T_g\) is the glass transition temperature and \(T_m\) is the melting point of the material [13]. The good GFA of some multicomponent alloys, such as Zr-Al-Ni- Cu, can be attributed to several factors, including the atomic size mismatch between constituent elements, negative enthalpy of mixing, and the multicomponent nature of the system. These characteristics contribute to the alloy’s resistance to crystallization during rapid cooling, thereby promoting the formation of the amorphous structure [14]. Composition, however, is one of the key design considerations influencing the capacity of an alloy to produce glass, and variations in constitution can impact the alloys’ GFA [15]. Another important design consideration is the very high cooling rate, which can be achieved by rapid extraction of heat from the system (rapid quenching). Few compounds could be created in the shape of strings of ribbons, foils or strands since these geometries allow rapid heat extraction. Rapid quenching methods like melt spinning and splat quenching [16, 17] are frequently used to process and create ribbon-like amorphous alloys.

A variety of amorphous alloys were subsequently produced using solid-solid and solid-gas reactions [18, 19]. Irradiation and ion implantation [20], mechanical alloying [21], and electrodeposition [22] were used to modify the surfaces of MGs. Thin film MGs (TFMGs), which offer a wider scope of compositional possibilities for amorphization and GFA that can be further optimized, have been the subject of extensive research in MGs [23]. After undergoing annealing within the supercooled liquid region, the as-deposited multicomponent alloy thin films were found to transform into an entirely amorphous state.

Due to its limited production capacity, MGs are not capable of supporting large-scale production. However, MGs have potential applications in many fields. NASA’s program for space exploration makes use of MG in applications such as spaceship shielding and solar wind collector [24, 25]. Additionally, MG has been utilized in electrical components, and micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), involving the use of resonators [26]For a more detailed discussion on MGs application including that of biomedical devices, energy, and sports the reader is referred to the excellent review article by Inoue and Takeuchi [11]. Concomitant to the pioneering experimental efforts in the synthesis, applications and the fundamental structure–property relations of MG, rapid advancements in theory, modeling and simulations of MG have also proved to be of great importance in the advancement of the field. The theoretical underpinnings of MG and the development of computational techniques and results over the past decades all the way to the state-of-the-art simulations in understanding the complex structure–property relations in MG, optimization of glass formability and properties with data-driven approaches, forms the crux of the current review.

Theoretical underpinnings of MGs

This section explains the most important theories behind formation of glasses, models governing the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of MGs, and concepts that explain the relationships between the structure and thermo-mechanical properties.

Kinetic factors that govern the glass-forming ability (GFA)

Synthesis of glasses from metallic alloy liquids is an important task considering the potential applications of MGs [6]. However, understanding the dynamics of glass formation is a complex issue, considering multiple factors affecting the same, including rate of nucleation, atomic packing factor, interatomic strength, among others [27, 28]. Metallic alloys have different GFA depending on the kinetics of the transition between thermodynamic states in the liquid state which compete among themselves during the cooling process. Typically, metallic alloys possess a negative heat of mixing, which plays an important role in glass formation kinetics. The negative heat of mixing ensures the melt phase’s stability and overviews the melt’s atomic mobility. GFA is also determined by the certain behaviors of the alloy. For instance GFA further depends on alloy’s ability to undergo (a) partitionless melting (forming a single-phase crystal without competing phases) and (b) stable or metastable primary crystallization [29].

One naturally expects the MG system to have a large GFA for ease of glass formation. This is typically achieved by having multiple constituents in the system (which leads to destabilization of the crystalline counterpart), having a significant size ratio distribution of the constituent elements (that increases the “frustration” in forming a crystalline state) [30] and having a negative enthalpy of mixing as highlighted above. To optimize the composition of MG to get the maximum GFA, experimental observations of the crystallization rate with varying composition can be carried out and the compositional area where the crystallization rate is slowest is likely to have the highest GFA, as verified in Al-Gd-Ni alloys [15, 31].

Transition Temperatures during glass formation

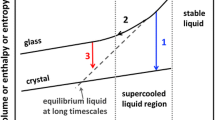

Considering the fact that there is a narrow temperature range over which glass transition occurs, three transition temperatures can be defined in this range, describing the different dynamic responses when passed through these temperatures [32]. These temperatures are the Glass Transition Temperature (also known as alpha relaxation), Mode-Coupling Transition Temperature and the Kauzmann Temperature. Glasses may also show several relaxation phenomena (structural changes that traverse the potential energy landscape across various glassy states) at specific characteristic temperatures. These relaxations are denoted as secondary (\(\beta\)) or tertiary (\(\gamma\), \(\delta\)) relaxations. All these temperatures are below the material’s melting point.

Glass transition temperature

The glass transition temperature is the temperature (denoted as \(T_\text {g}\)) below which the liquid turns to glass when cooled at a rate greater than a threshold cooling rate [33]. Glass transition is often designated as a second-order phase transformation, where the second derivative of the free energy shows a discontinuity during the transition. During the cooling process, this manifests as a sudden decrease in the heat capacity around \(T_\text {g}\). Therefore, this temperature is generally measured experimentally when \(C_\text {p}\) shows an increase while heating with a predefined heating rate [34]. It is to be noted that the experimentally observed \(T_\text {g}\) differs from the ideal \(T_\text {g}\); the latter is achieved when there is an infinite cooling rate (not experimentally possible), where the system attains multiple states, above \(T_\text {g}\), before landing on a very thermodynamically non-crystalline stable state [35]. It has been observed that around \(T_\text {g}\), theoretically, the liquid follows the empirical Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann equation instead of the Arrhenius form. It is also around \(T_\text {g}\) where the transition from Arrhenius form to the Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann equation (more on this in "Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann-Hesse (VFTH) Equation" section) occurs [36]. Though \(T_\text {g}\) is not a well-defined thermodynamic parameter, it is of significant importance to measure or estimate this temperature, since many interesting physics phenomenon occurs around the this temperature, like that showed by Mendelev et al. [37] where a significant change in Cu-Zr bond compared to Cu-Cu bond, near \(T_\text {g}\), for \(Cu_xZr_{1-x}\) MG was observed.

Mode-coupling transition temperature

This theoretical temperature is well above \(T_\text {g}\) [38]. Under conditions below Mode-Coupling Transition Temperature, the liquid diffusion is predicted to halt. The dynamics associated are as follows: atomic/molecular transport will be medium-assisted, and multiple atoms/molecules will fuse to form clusters that transition into new configurations upon thermal activation. This dynamics can also be mentioned as the sharp characteristic change of the material from an ergodic regime to a non-ergodic regime. This transition can be attributed to the low-frequency local order atomic excitation [39].

Kauzmann temperature

This is a theoretical temperature below the experimental \(T_\text {g}\) when the excess entropy (the difference between the absolute entropy of liquid and the absolute entropy of the crystal) vanishes [36]. Since the Kauzmann Temperature originates from thermodynamic considerations (through the specific entropy), it can also be called the ideal thermodynamic \(T_\text {g}\) [40]; however, in reality, this is quite challenging to be identified experimentally. This is true even in simulations and can only be inferred from extreme condition data [41]. Interestingly Kauzmann Temperature is accompanied by Kauzmann paradox, which stipulates that supercooled liquid’s entropy when extrapolated tend to have zero entropy at positive temperature and Kauzmann hypothesized that supercooled liquid would crystallize before reaching a zero entropy. Commonly, researchers identify Kauzmann temperature as when supercooled liquid supposedly crystallizes. However, the original hypothesis by Kauzmann did not specify that the liquid-to-crystal transition would occur at a particular temperature but rather over a range [40]. More detailed discussions on the Kauzmann Temperature can be found in the excellent review by Welch et al. [40]. The paper also discusses the role of Kauzmann Temperature in many applications including that of studying the ideal glass hypothesis presented by Gibbs and DiMarzio [42], which had applications in investigating polymer melts and other materials. Though several research groups have explored the role of Kauzmann Temperature in glass transition over the past six decades, no conclusive evidence has been established to either support or disprove the hypothesis of Kauzmann or the existence of the Kauzmann Temperature.

Though Kauzmann temperature seems unrealistic, the notion behind its existence is definite proof that glass transition has a rigorous thermodynamic interpretation. It is well-known that glass transition and the associated relaxation phenomena at sub-\(T_\text {g}\) temperatures are also dominated by kinetics, and can often be quite slow [28]. The dynamics of glass transition and relaxations are explained in the following sections.

Predicting the GFA of metallic alloys

It is clear that MGs are formed by a quenching process, where the metallic alloy is first melted and then cooled rapidly at a high rate. This process can be labeled as a physical vaporization deposition technique, which produces a kinetic and thermodynamic stable glass system called ultrastable glass, as this technique was demonstrated by Swallen et al. [43] for molecular glass formers: 1,3-bis-(1-naphthyl)-5-(2- naphthyl)benzene (TNB) and indomethacin (IMC), to bypass the kinetic restrictions to reach lower energy stable or metastable state [43, 44]. Though the mentioned technique is a good method to produce MGs, not all liquid phase metal alloys form MG when they are cooled rapidly. Take the case of \(Cu_{64} Zr_{36}\), which has a lesser tendency to crystallize, whereas \(Ni_{64}Zr_{36}\) tends to have the tendency to form a crystallized or ordered structure [45]. This leads to the question of what makes a liquid metallic alloy to either crystallize or amorphize. This question is important, though the driving force for crystallization in Bulk MG-forming liquids is typically much smaller than for conventional glass formers [46].

Strong and fragile liquids

MGs are disordered systems where the atomic positions, unlike crystalline structures, cannot be associated with the theoretical Bravais Lattice [47]. This same disordered structure can indeed be seen in the case of liquid. Though both the structures are similar, i.e., being disordered in nature, the transition from liquid to glass cannot be looked at as a static phenomenon but as a dynamic one [48], where the atoms in glassy state diffuse as a cluster in a collective manner, unlike in a liquid. Similar to glass and liquid structure, the same can be said for glasses and amorphous solids. Though both mean the same, in material science, they are different. Glasses are a subcategory of amorphous solids; not all amorphous solids, like rubber plastics, can be glasses. This is because, during the cooling process of liquids to form glasses,- (a) there is a sudden decrease in the transport properties of the liquid when T reaches below \(T_\text {g}\), (b) transport properties of the liquids deviate from the Arrhenius law, (c) high viscosity can be witnessed, which inhibits the system from attaining equilibrium, at least from an experimental perspective.

Variation of viscosity with temperature. Glass transition occurs when \(T = T_\text {g}^{*}\). Reproduced from Ref. 49 with permission.

Considering that amorphous glasses are formed from the rapid cooling of the liquids, it is only logical to classify them accordingly based on their GFA. Liquids here are classified as strong and fragile. To characterize these two types of liquids: strong liquids have a broader structure with directional bonds, whereas fragile liquids are the quite opposite which have less or non-directional interactions [50] and are less rigid. To distinguish between these two liquids properly, consider the Angell Plot, which plots the logarithmic viscosity of the system against scaled temperature (See Fig. 1). The slope obtained from this plot gives us a numerical value (defined as fragility) that can be used as a metric to distinguish between these [51]. Strong liquids tend to follow the Arrhenius form, where \(\log (\eta )\) is proportional to the inverse of temperature, as opposed to fragile liquids. This can be attributed to the collective movement of atoms in fragile liquids due to a less rigid system, as opposed to the strong fluids, which are movement-controlled due to stronger bond relations [52]. Thus, systems with higher fragility values tend to form stable glasses more than materials with lower fragility values.

The kinetic study of undercooled liquids gained momentum owing to the nature of the undercooled liquids: high viscosity and fragility. High viscosity (high density) is due to different types of atom elements, which exhibit individual local order [53]. However, to study the kinetics of equilibrium liquids undergoing glass transition using advanced techniques, many considerations have to be made, including longer relaxation times of liquids and prevention of crystallization and chemical decomposition process. Low viscosity above the melting point and low apparent activation energy for flow are characteristics of kinetically fragile liquids. The activation energy for flow dramatically increases when the viscosity of fragile liquids approaches \(T_\text {g}\). At the melting point, strong liquids, such as silicates, have high melt viscosities that are up to eight orders of magnitude greater than those of fragile liquids [49].

The potential energy landscape

The Potential Energy Landscape (PEL) is an important tool to understand and predict the properties of amorphous systems. It is the landscape of the potential energy as a function of the collective, 3N dimensional configurational space of the system at 0 K, where N refers to the number of atoms, and each atom has three degrees of freedom (along the x, y and z Cartesian axes). The PEL is developed in principle by obtaining the potential energy at each accessible atomic configuration. Assuming that the plot is continuous, there are specific points in the landscape where the potential energy gradient is zero. These points, the local minima or maxima are the configurations that are metastable or unstable, respectively and the transition states between any two minima are the saddle points where the gradient of gradient changes from positive to negative. It is to be noted that the global minima in the PEL is the material’s thermodynamically stable structure [32, 54]. Theoretically, it is possible to obtain the value of the number of basins present in PEL. A relationship has been developed for a monoatomic, N-atom system, which correlates the number of basins with N [55]. It becomes very difficult to find all the basins configurations available for the system for a larger value of N, even with computer simulations. It is, therefore, a current well-established challenge in the material science community. Like basins, one notable feature of PEL is a particular portion of the landscape called super basins which portrays a collective group of basins like funnels. Super basins are usually present in the PEL of material, which leans towards crystallization upon cooling and usually occurs around the global minimum [56].

To illustrate the above-mentioned features of PEL, take the cases of \(KCl_{32}\) and \(Ar_{19}\), which are potential glass-forming systems. It has been observed that \(KCl_{32}\) forms a crystal structure, and \(Ar_{19}\) forms an amorphous structure [57]. Inspection of PEL for both these systems gives us a definite explanation for their respective behavior. \(KCl_{32}\) has a funnel-like shape (super basins) in PEL. On close scrutiny, this can be described as an inverted triangle with sides as the staircase and vertex as crystalline global minima. However, \(Ar_{19}\) has no notable presence like super basins and has only basins spread across the PEL. Upon cooling, \(KCl_{32}\), trapped in the funnel region, reaches the global minima to become crystallized. However, \(Ar_{19}\) seems unable to reach the global minima and remains amorphous by reaching the state whose energy is close to that of the global minima. This can only mean that glassy systems need higher energy to reach the global minima state, which seems impossible while cooling. Quantitative representation of if a material will reach the global minimum of the crystal structure can be foreseen by considering the ratio of \(T_\text {f}\) (Temperature at which the global minimum is reached) and \(T_\text {g}\) [58]. The larger the ratio represents, the higher the chance the material is trapped in a global minima state (crystal structure or native structure), and if else otherwise. It has been calculated that \(Ar_{19}\) has a lesser ratio, and \(KCl_{32}\) has a higher ratio, which matches the above statements. This quantitative representation, therefore, proves the mentioned illustration about PEL.

Atomistic PEL can be employed to find correlations between the local structural excitation occurring in the atomic scale in metallic glasses with its local atomic environment. For instance, Swayamjyoti et al. [59] using Activation Relaxation Technique (ARTn) explored the atomistic PEL, under zero applied stress, to identify local structural excitations (LSE) in 3D Lennard Jones glass samples, which are found the depend (though weakly) with its local atomic environment. The barrier energies of these LSE correlate weakly with local cohesive energy, the lowest eigenshear and excess free volume. Swayamjyoti et al. [60] further extended the study to include applied external strain and find how it affects LSE and its corresponding structure and barrier energy. In another study, correlation between the density of the configurational states (obtained from PEL) and the material liquid’s fragility was seen [61], where the density of the configurational state can be defined as the probability that a configuration of specific energy will appear on the PEL. Fragile liquids have a very small number of basins in PEL due to the lesser number of atoms (N) present in the system (based on the correlation between N and no of minima), which means a lesser configurational state density. Crystal structures, which, as mentioned before, have super basins (funnel structure) in PEL and have larger configurational states [62]. It has been observed that strong liquids have a configurational state density between fragile liquids and crystal structures. Another correlation, in the same way, is the interlink between PEL, specifically the basins present in PEL (which are separated by barriers) and atomic relaxation. In theoretical research (with support from experiments), two relaxation mechanisms (\(\beta\), \(\alpha\)) are believed to be present in liquid-glass physics. \(\beta\) relaxation mechanism is the movement of a small number of atoms (around 10) and thus is considered the fastest relaxation mechanism. \(\beta\) relaxation is characterized by the system’s movement in PEL from a local minimum to other neighboring local minima via a saddle point. \(\beta\) relaxation is considered a reversible process at a low temperature, well below the \(T_\text {g}\). \(\alpha\) relaxation, on the other hand, is the bulk movement of atoms (around 40) and thus is considered the slower relaxation mechanism. \(\alpha\) relaxation is characterized at a higher temperature (below \(T_\text {g}\)) followed by the instability of the surrounding elastic matrix. With PEL, \(\alpha\) relaxation can be described as the \(\alpha\) hill, composed of many \(\beta\) relaxations [refer to Fig. 5(c)]. Thus, \(\alpha\) relaxation is considered irreversible due to the complex nature of reversing the multiple \(\beta\) processes in a single stretch. Experimentation on the liquid system around \(T_\text {g}\) states the presence of only one mechanism (\(\alpha\)) where extensive atomic component diffusion occurs. On decreasing the temperature, the mechanism gets split into \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), respectively. However, after a certain point, while decreasing the temperature, \(\alpha\) relaxation, the primary relaxation mechanism, freezes. \(\beta\) relaxation mechanism, the secondary relaxation mechanism which gets activated at low temperatures, remains intact even at a very low temperature, followed by the decrease in diffusion of atoms [63,64,65].

Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann-Hesse (VFTH) equation

So far it is clear that glass transition dynamics is a highly complex process, and as such experimental research will not fetch the holistic understanding we seek. To overcome this predicament, multiple mathematical models have been developed including VFTH and Mode-Coupling Theory. In this review paper we will limit ourselves to VFTH.

If crystallization can be prevented, a glass-forming material can retain a disordered, liquid-like structure below its melting point. From the liquid state, as the system is quenched below the melting point (supercooled), it is observed that the relaxation time of the system increases dramatically. Experimentally, an accepted criterion for glass transition is that the relaxation time in the glassy state is above 100s with the ensuing viscosity being at least \(10^{13}\) Poise [66]. Below \(T_\text {g}\), the \(\alpha\) relaxation process in glass demonstrates a non-exponential response with a broad range of relaxation times. It is to be noted that the relaxation time sharply increases while approaching the \(T_\text {g}\), a deviation from the Arrhenius relation, which occurs at temperatures below the \(T_\text {g}\) but well above \(T = 0\) K [28].

In describing the temperature dependence on the dynamics of glass-forming liquids, the VFTH equation has been most applicable for cases where the molecular weight of the system is low, and for macromolecular systems. Moreover the equation can be used around a broad range of temperatures, especially in the vicinity of the glass transition [66].

VFTH is expressed through the equation below:

In Eq. 1, \(\tau _o\) is the pre-exponential factor, and B, \(T_o\) are the specific adjustable factors. Here, \(T_o\) is close to \(T_{\text {Kauzmann}}\), and \(B = DT_o\) with D being related to fragility.

The applications of VFTH are numerous. Being empirical, the VFTH model can be coupled with other models like Adam-Gibbs Theory [52] (relating structural relaxation time and configurational entropy). From the correlations exposed, it can be stated that the relevant theoretical information regarding the liquid glasses may be obtained from the VFTH parameters (relaxation time, B, \(T_o\)) associated with a given system, including fragility, free volume, relaxation times at divergent temperature, and limit frequency (linked with the material’s structure). VFTH parameters can also predict the material’s dynamics and properties at temperatures (like Kauzmann’s Temperature) which cannot be analyzed experimentally [66].

Computational techniques to understand and optimize MGs

From the middle of last century, with rapid advancement in computational technologies coupled with the fact that computational resources were available at ever-decreasing price points, it is no surprise that they are gaining popularity in research, especially in all branches of material science, including MG. Broadly, these computational methods yield valuable insights about the structure, properties and behavior of MG that are either impossible or difficult to observe experimentally. In addition to saving time and resources, these techniques allow researchers to explore a wide range of materials and conditions relatively fast [67]. The broad classes of computational techniques or methods for performing simulations of MG include Density functional theory, Molecular Dynamics, Cluster expansion and Continuum modeling, as elucidated below:

-

1.

Molecular dynamics (MD) Fundamentally, MD solves Newton’s equation of motion in order to calculate the trajectories of atoms. Once a simulation involving large numbers of atoms are run under certain conditions kept constant, it allows the user to gather enough statistics, from where the thermodynamic parameters can be estimated. Alternatively we can change the condition in a systematic way and study the kinetics/dynamics as well. It however cannot account for the finer quantum mechanical details, particularly for the aspects that do not have any classical analogue. This simulation model is widely used to study the behavior of materials at the atomic and molecular levels. They can provide valuable information on materials’ structural, thermodynamic, and transport properties and the kinetics of processes such as diffusion, phase transitions, and chemical reactions [68]. MD simulations are routinely used for elucidating the complex structure–property relations in MGs, such as tensile and compressive behavior, thermo-mechanical behavior, atomic relaxations [67, 69].

-

2.

Cluster expansion (CE) It is a statistical mechanics-based technique that can be used to model the energetics of materials as a function of their atomic arrangements. Using a set of cluster functions that represent the energy contribution of each arrangement, it involves the expansion of the energy of a material as a series of terms that depend on the local environment of each atom [70, 71]. When we use a Taylor series, we estimate the function at an unknown location, say at \(x+\Delta x\), by using the function’s behavior (its value and all its derivatives) at some known location, say at x. On a very similar note, cluster expansion attempts to estimate the properties of an unknown cluster, by expanding it in terms of increasing cluster size with known properties. This approach is very attractive, since the computational resource requirement is not prohibitively high even for bigger systems. Therefore, this method may turn out to be a crucial tool to attack an unsolvable NP-hard problem, and break them into an infinite series of solvable and easy problems. At the very end, one then hopes that the higher-order terms become increasingly inferior and the series can be terminated (converged) and a good estimation of the properties can be made.

-

3.

Density functional theory (DFT) This method is based on the foundations of quantum mechanics. To understand the properties of any material, we need to understand the interactions between atoms, which is primarily mediated by the electrons. However, the electrons are purely quantum mechanical entities (after all, the entire subject of quantum mechanics was developed to understand the electrons). This method solves the Schrodinger equation. However, it is computationally very expensive, therefore impractical, to solve the Schrodinger equation for the wavefunction. Therefore, we make lots of simplifying assumptions and use electron density as a proxy for wavefunction, and push all the un-accounted for contributions into a parameter, we call exchange correlation function. This computational method is widely used to calculate materials’ electronic structure and properties. Based on the solution of the Kohn-Sham equations, it describes how electrons behave in an external potential that may be approximated as the sum of the electrostatic potentials due to nuclei and electron density [72]. As an example, DFT was used to find the ground state structures of Cu-Zr MGs and, with the assistance of Crystal structure AnaLYsis by Particle Swarm Optimization (CALYPSO), it was possible to determine the correlation between the composition and the chemical reactivity [73].

-

4.

Continuum models This is a classic coarse-grain approach to solve physical problems that does not intrinsically rely on the atomic description of the material. It describes the behavior of materials using mathematical models that represent the material as a continuous medium. This can involve partial differential equations describing mass, momentum, and energy transport through the material [74]. For example, continuum modeling was used to understand the time-dependent plasticity of Cu-Zr MGs, which can further be extended to analyze the creep dynamics in the material [75].

These different approaches cover different time and length scales and can be combined in many ways to holistically and systematically understand the materials. In many research studies, DFT and MD simulations were used together to obtain the characteristics and properties of MGs. For example, DFT was used to obtain the second nearest neighbor modified embedded atomic method (2NN MEAM) parameters, which is required for obtaining the potentials of the Mg-Zn-Ca-Sr bulk MGs system. The obtained potential serves as the input for MD simulation to study the characteristics of Mg-Zn-Ca-Sr bulk MGs [76]. Likewise, the continuum model can be combined with DFT. For instance, to develop a continuum model of the elasticity of MGs for dislocation dynamics analysis, DFT can be used to characterize the elasticity of MG [77]. Similarly MD simulations can be used in association with Continuum modeling in computational analysis. For example, MD simulations can be employed to investigate the correlation between cryogenic rejuvenation in MGs and the heterogeneity of the glass structure by modeling the MG structure. The examined local thermal expansion heterogeneity, can then be combined with continuum modeling to determine internal stresses resulting from thermal cycles [78].

These studies demonstrate the power of combining multiple methods to model MGs’ atomic structure and properties. By using these methods in combination, researchers can gain a more comprehensive insight on the characteristics of MGs and design innovative materials with optimized properties.

Structural characteristics of MGs

Understanding the structural characteristics of MGs is of paramount importance to predict the static and dynamic properties. In the following section, some of the standard quantification of structural characteristics of MGs are elucidated.

Radial distribution function

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), also known as the Pair Correlation Function is one of the most important structural tools used widely in the structural characterization of materials. RDF is a measure of the average probability of finding a neighboring atom within an arbitrary radial distance from each atom. In other words, RDF can be used to find the average distance of atoms around a specific atom [79], which then can be utilized to calculate structural properties. Besides, RDF can also be used to understand certain behavior of MG systems such as the relaxation behavior [80] of the system. For instance Wessels et al. [81] identified the abnormal sudden changes in the local structure (monitored through RDF) and specific heat and attributed it to be a rapid chemical and topological ordering in the supercooled \(Cu_{46}Zr_{54}\) liquid.

RDF can be understood as a measure of the probability of finding a pair of particles whose interatomic separation is r. For a system with N particles, to calculate RDF, we first determine the \(N(N-1)/2\) interatomic distances and obtain the largest value of r possible (denoted by R). Taking \(\left( \left[ r, r+\delta r\right) \right)\) as the measure of number of particle pairs in the r range of \(\left( \left[ r, r+\delta r\right) \right)\), we define particle density \(p\left( \left( \left[ r, r+\delta r\right) \right) \right)\) which is the ratio of number of particles present (\(\rho\)) and the volume of considered range of r. Particle density thus can be written as,

A continuous expression of the above particle density gives us the RDF, and can be expressed as:

RDF is quite useful in understanding the local structure, coordination and packing density of atoms. Thus, for a liquid/glassy system, normalized g(r) starts at 0 (since no pair can be found at \(r=0\)) and remains the same till a certain value of r and then extends to describing the profile of atom pairs closer to each other (referred to as the first shell). The presence of a shell of neighbors is identified by the presence of a maxima and a minima in the graph. A second shell can also be seen in MG systems. Considering that most of the systems are isotropic in the longer range, the value of normalized g(r) reaches 1 and remains the same for larger values of r.

The first shell yields an important quantity, the coordination number of the MG system, i.e., the average number of neighbors that each atom has. The area under the g(r) curve till the minima of the first shell directly yields the coordination number and is characteristic of the nature of the MG system.

In the context of heterogeneous material particle interaction like in a binary (say A-B) system, three interaction pairs are expected including: A-A, A-B, and B-B. Having expressed RDF for homogenous particle interactions (A-A, B-B), the defintion of heterogeneous RDF (A-B) can be expressed as

This expression can also be used for heterogeneous system with n unique elements which has a total number of \(^{n}C_2\) interaction pairs. In Eq. 4, \(\rho _{AB}\) is the number density of particles of element B with respect to A.

A typical RDF for a MGs looks like the one shown in Fig. 2(a), for the Mg-Al MG. As opposed to crystalline phases that show characteristic peaks at specific pair separation distances corresponding to lattice planes, in glasses, there is just one small peak at small separation distances, that corresponds to the SRO that is ubiquitous in glasses and liquids, followed by a rapidly decaying signal that tapers to 1, indicating distributions akin to an ideal gas of atoms.

(a) RDF of \(Mg_xAl_{100-x}\) at different compositions, where the curves are shifted for clarity. Reproduced from Ref. 79 with permission. (b) Pictorial representation to explain \(G_4\) correlation. Here, the individual atomistic units are weighted based on the computed self-intermediate function. Reproduced from Ref. 82 with permission. (c) Intensity Correlation Function [g2(q, t)] measured at different waiting times. Reproduced from Ref. 83 with permission.(d) Intensity Correlation Function [g2(q, t)] showing exponential time dependence relationship in Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) experiments for representative volume fractions. Reproduced from Ref. 84 with permission.

As seen from Fig. 2(a), the first peak occurs at around \(2.8\text{\AA }\), indicative of the SRO distance. The second (smaller) peak can be seen to split into two sub-peaks, which signifies the MG formation in the system. In fact, the split in the peak can even be said to be a criterion for MG formation [79], which is nearly universal for all MGs. This corresponds to the icosahedral/distorted icosahedral ordering [85], which are incompatible with long-range crystalline order, and therefore a crucial criterion for glass formation in metallic systems. It is also to be noted that minor variations in the composition does not lead to significant changes to the RDF profile. The calculation of RDF in a molecular simulation is formally equivalent to the analogous experimental measurement of the X-ray or neutron diffractogram of the MG sample, in the Fourier-transformed domain, typically referred to as Structure Factor. Thus any simulation result with RDF analysis is mostly compared with experimental Structure Factor to verify the model’s authenticity. For a more detailed discussion including derivation of the RDF from structure factor, the reader is referred to the excellent text by Kittel [86].

Intermediate scattering function

The Intermediate Scattering Function (ISF) is related to the density correlation function and quantifies the relaxational dynamics of the system. For instance, considering the complex nature of glassy dynamics, the corresponding aging dynamics of glassy state, typically represented by structural relaxation time, can be measured by keeping track of the long period decay of ISF.

ISF is often corroborated with experimental data to quantify relaxation and aging in MGs. Ruta et al. [83] characterized the aging of Mg-Cu-Y MG using ISF and found that the glass transition was accompanied by (a) crossover of stretched exponential to compressed exponential of ISF at glassy state and (b) presence of two distinct aging regimes below the \(T_\text {g}\). Ruta et al. correlated experimental data obtained from XRay photon correlation Spectroscopy (XPCS) i.e the intensity (I at two different times \(t_1\), \(t_2\) with \(g_2(q, t)\) (representing ISF, see Eq. 5) using the Siegert relation, as shown in Eq. 6 [where B(q) is a setup dependent parameter]. f(q, t) from Eq. 6 is then paired with the empirical Kohlrausch Williams Watt model (Eq. 7) to observe the effect of waiting time on physical aging dynamics in Zr-Ni MG system (see Fig. 2(c)). The final form of the intensity correlation is expressed through Eq. 8, where \(\tau\) represents the characteristic relaxation time, \(\beta\) is the stretching parameter which quantifies the deviation from a simple exponential behavior and \(C(q,T) = B(q)f_q^2\).

In another research (by Brambilla et al. [84]) related to the colloidal hard sphere system, the data from dynamic light scattering and computer simulation in conjunction with ISF was used to dispute the understanding of Mode Coupling Theory (MCT) in hard sphere systems. Brambilla et al. stated that though MCT may have been a key player in the dynamical slowing during the relaxation phase at critical volume fraction, for larger volume fraction, the time-scale behavior is exponential and not linear [Fig. 2(d)], which validates the point that MCT might be avoided in colloidal materials like glass formers, contrary to the previous understanding.

Four-body (\(G_4\)) correlation

In amorphous alloys, the description of atomic interactions goes beyond merely relying on the pair correlation function typical in crystalline materials. Instead, higher-order correlations play a significant role. A four-body correlation function (\(G_4\)) provides a detailed statistical measure of the likelihood of finding four atoms at specific positions relative to each other as a function of spatial distribution (density), orientation, and temporal evolution, which can be seen from Fig. 3(a, b). As a function of density, \(G_4\) reveals the SRO and MRO in amorphous solids. The orientational dependency details the geometric arrangement of atoms in an anisotropic environment, while the temporal evolution enables the study of dynamic behaviors in MG, such as structural relaxations [52, 82, 87, 88]. For instance, \(\beta\) relaxation in MGs [82] can be studied by computing the microscopic self-intermediate functional (F) of different atomistic units at the beginning. Denoted through scattering vector (k), position vector of the atomistic unit (r), and time (t), \(G_4\) is given as:

where \({{{\overrightarrow{r}}}_{\overrightarrow{mn}}}={{{\overrightarrow{r}}}_{\overrightarrow{m}}}-{{{\overrightarrow{r}}}_{\overrightarrow{n}}}\), represents the distance between the \(\text {m}^{\text {th}}\) and \(\text {n}^{\text {th}}\) atoms [refer to Fig. 2(b)], V and N represents the volume of system and number of atoms in the system and \({\hat{F}}\) is defined as

where the calculation in Eqs. 9 and 10 is being done in the inverted \(k^{\text {th}}\) space.

(a) 3D plot of \(G_4\) at 507K (b) Contour plot of \(G_4\) over \(\Delta r\) and \(\Delta t\) (c) Obtaining characteristic length (\(\varepsilon\)) and \(\vartheta\) from the contour plot for a given value of \(G_4\), which are then used to obtain the correlation length, as \(\xi\) is twice of \(\varepsilon\). Reproduced from Ref. 88 with permission. (d) correlation length (\(\xi\)) variation with Temperature (e) Plot of \(\xi\) vs. \(\log (\tau )\) to verify Adam Gibbs theory. Refer to [52] to know more about Adam Gibbs theory. (f) Log-Log plot of \(\varepsilon\) and \(\tau\) to verify inhomogeneous Mode-Coupling theory. Refer to [52, 87] to know more about inhomogeneous Mode-Coupling theory.(g) Semi-Log plot of \(\tau\) vs. \(\varepsilon /k_BT\) to verify first-order transition theory. Refer to [89] to know more about first-order transition theory. Reproduced from Ref. 88 with permission. (d) to (e) explains the process of obtaining the characteristic length and time for a Pt-based MG nanowire.

In a different research (by Zhang et al. [88]), to study supercooled liquids and the associated dynamics of their atomic arrangement, \(G_4\) was used to capture the growing dynamic correlation length (\(\xi\)) and relaxation time (\(\tau\)) upon cooling the liquid towards \(T_g\). Figure 3 illustrate how \(G_4\) was used to characterize a Pt-based MG system.

Softness and stiffness

The local structure in MGs (ranging from individual atoms to small clusters of atoms) is a great tool for probing the properties of glassy liquids and for predicting the response in terms of diverse properties such as relaxation, aging and the mechanical behavior [90, 91]. Over the past decade, extensive research has focused on the characterization of local structure of amorphous solids [92,93,94,95]. Structural features in MGs can be classified into two subsets, i.e., the (i) pure structural ones and (ii) thermodynamically derived ones. The pure structural features include coordination number, atomic volume, Voronoi index, local fivefold symmetry, two-body entropy, inversion symmetry breaking and the bond orientational order to name a few.

In contrast, thermodynamic features include characteristics derived from pure structural features with appropriate thermodynamic inputs, including soft vibrational modes, vibrational mean-squared displacement, flexibility volume, local yielding stress, local thermal energy. Both groups are equipped to predict particle rearrangements in the glass [92,93,94, 96]. Compared to the former group, the latter is of more interest to researchers, mainly while predicting the deformation sites. In this context, stiffness, the response of an atom’s position to thermal stimulation [97] (see Eq. 11) defines the atomic response in terms of displacements during thermal fluctuation. In Eq. 11, \(K_i\) denoted as the atomic stiffness, which can also be understood as a particle-level spring constant for the cage effect of atoms in a glassy environment, \(\left<\left| \Delta r_i (\tau )\right| ^2\right>\) is the vibrational mean-squared displacement of the ith atom throughout a particular duration \(\tau\). Defining atomic stiffness paves the way for establishing a connection between atomic positions and athermal plastic excitation (here stiffness) using machine learning techniques, as will be discussed in more detail in "Machine Learning applications in MGs" section [98, 99].

Though stiffness seems vague, it can be interlinked with many other concepts. According to Johnson’s cooperative shear model, a correlation exists between shear transformation and stiffness [100], which can also be connected with physical properties like viscosity, where it was observed that the viscosity increases in an exponential manner with stiffness [97].

Directly linking the structure and stiffness is also possible. Using RDF, a functional structure representation, stiffer atoms have RDF with solid-like features, where the first peak is higher and the second peak is split. An opposite observation was used for identifying lower stiffness atoms, indicating the shrinkage in the curve due to the glass-to-liquid transition. Based on Johnson’s cooperative shear model, a similar stiffness-structure observation was made for lower stiffness systems. A system with low atomic stiffness can be classified as percolated or isolated soft zones, which leads to the creation of shear transformation zones that are eventually responsible for the deformation in MGs [97].

Like stiffness, softness is another important established quantity, especially in amorphous materials, which is related to the rearrangement of atoms. For many materials, the deformation is expected to follow the following sequence: application of strain \(\rightarrow\) rearrangement of atoms \(\rightarrow\) plastic deformation \(\rightarrow\) failure [101]. Considering the same sequence holds for MG, the rearrangement of atoms is quite important and seems to be the effective cause for the failure. It is to be noted that atomic rearrangement is an involved concept associated with many factors, including local structure and energetics [102, 103]. When compared to crystalline materials, where the rearrangement occurs around well-defined dislocation or defect sites, disordered solids, which are usually homogeneous, become active and tend to perform proliferated rearrangements above yield strain, leading to the formation of “shear bands", which inevitably leads to failure of the material [104, 105]. Softness here performs the role of predicting rearrangement and thus helps the researchers understand the dynamics of glass systems and their associated aging process [90, 91, 106, 107].

Softness is an atomic quantity that depends only on the particle’s structural configuration. It is, therefore, possible to determine the softness of a structure from any static picture (or snapshot) taken along the trajectory of deformation, time, or temperature. Softness can be viewed as a weighted integral over the local pair correlation function g(r) [106]. The tendency for atoms to rearrange can be gauged based on the softness. For higher softness, the energy needed to rearrange linearly decreases, thus increasing the tendency for the particles to rearrange, especially for binary Lennard–Jones (LJ) and oligomer glasses. However, this cannot be generalized since exceptions do exist. Softness can be only perceived as the likelihood for the rearrangement to occur and not serve as an absolute determining factor [91]. This is because softness is influenced by many factors, including yield strain, temperature, and relaxation time [90, 91, 101]. The softness value is typically obtained using machine learning methods, whose input will be the structure-defined functions [97]. More details on the characterization of stiffness and softness will be discussed in "Machine Learning applications in MGs" section).

Softspots, shear bands and shear transformation zones

A theoretical construction often invoked to explain the flow and deformation characteristics under the application of an external load is the concept of “soft spots", which remains an area of ongoing research. One proposed mechanism for their formation is the presence of free volume—that is, empty spaces between atoms—as potential sites for rearrangement during deformation and thus lead to soft spots forming in STZs. Another suggested mechanism includes topological defects like disordered regions or foreign atoms which create local structural inhomogeneities that lead to soft spots. Soft spots can be defined by their size and distribution in materials. Recent studies have demonstrated that soft spots tend to grow, form or cluster near certain regions rather than being randomly distributed [107, 108]. Soft spot distribution has an enormous influence on mechanical properties of materials; for instance MGs with higher fractions of small soft spots exhibit greater ductility but reduced strength; while lower fractions of larger soft spots show increased strength but decreased ductility—small soft spots allow more localized plastic deformation while large ones lead to the nucleation and growth of larger shear bands.

Soft spots play a critical role in the mechanical properties of materials. Soft spots increase the propensity for atomic rearrangements during deformation, leading to greater plasticity. Soft spots also weaken materials by serving as sites for shear band [109] nucleation and growth, decreasing strength. Their impact on mechanical properties of materials depends on their size and distribution. Recent studies have demonstrated how mechanical properties of materials can be altered by manipulating their size and distribution of soft spots [110]. MGs with bimodal soft spot distribution exhibit both high strength and ductility due to smaller soft spots allowing localized plastic deformation while larger soft spots serve as sites for nucleation [111] and growth of shear bands. Deformation of a MG typically results in the formation of shear bands—areas of intense plastic deformation characterized by soft spots—forming localized regions of intense plastic deformation known as Shear transformation zones (STZs). As glass deforms, its atoms move and the corresponding potential energy landscape shifts as some of these localized regions lower their potential energy while others experience an increase in theirs. According to STZ theory, plastic deformation in MGs typically occurs within regions where microscopic energy flows are particularly conducive for shear deformation. Spaepen introduced the idea of free volume for MGs in 1977 [95], when he proposed that the microscopic mechanism responsible for macroscopic plasticity is a single atom migration. Argon came up with the concept of Shear Transformation in 1979 at MIT [94]. Building upon these early models, Falk and Langer, in 1998 came up with their seminal paper [93] on Shear Transformation Zone (STZ). In this paper, they discuss that, plastic deformation can occur in glasses via activating small, localized regions where atomic rearrangements needed for shear deformation are energetically favorable—known as Shear Transformation Zones (STZs)—which then become responsible for initiating and propagating deformation, shown in Fig. 4(a). STZs typically represent regions with high local atomic mobility where atoms rearrange themselves easily under applied shear stress; their size typically ranges between 1-20 atomic diameters and they appear randomly distributed throughout the glassy system.

Shear bands are one of the signatures of plastic deformation in MGs at the continuum length scale, characterized by localized regions of high shear strain [112]. When stretched over the domain of the material, these shear bands can lead to plastic deformation. Shear bands have been researched due to their significance in understanding the mechanical behavior of MGs. Shear bands occur when local stress exceeds yield strength of MG substrate [104]. At this stage, a region of material undergoes plastic deformation while its surrounding material remains relatively unchanged, leading to the creation of a narrow region with highly sheared material known as a shear band. Shear bands vary depending on the MG system being shear-banded; typically their widths fall within a range of several micrometers to several millimeters. Shear bands have an immense effect on MGs’ mechanical properties. Shear bands result in reduced material strength as strain accumulates locally in narrow sub-regions. Moreover, propagation of shear bands may even result in catastrophic failure when these strain concentrations meet and fracture material that was once solid. Shear bands may have some beneficial effects, as well, such as increasing material ductility through strain hardening. Shear bands in MGs have been the subject of extensive study by glass researchers for many decades [104]. Many experimental techniques have been developed to investigate shear bands, such as in situ deformation experiments using electron microscopy or X-ray diffraction. These experiments allow direct observation of shear band development during plastic deformation [104, 105].

Soft spots in STZs have an enormously detrimental impact on mechanical properties of materials, particularly MGs [113]. STZs are characterized by local elastic modulus of atoms that is lower than the elastic moduli of the surrounding atoms, leading to a greater probability of atomic reorganization during shear transformations. Soft spots in STZs are characterized by an increased tendency for atomic rearrangements when shearing occurs in these local regions. By understanding their role and nature in STZs, researchers can optimize mechanical properties for specific applications. One proposed mechanism for their formation in STZs is topological defects—regions in the MG where its local atomic arrangement deviates from ideal packing geometry, for various reasons such as foreign atoms or disordered regions during solidification. Topological defects could also contribute to the formation of soft spots.

Recent studies have demonstrated a correlation between soft spots in STZs and MGs’ mechanical properties [114]; such as higher soft spot concentration equating to greater ductility but decreased strength; or the opposite being true. MGs with lower concentrations of soft spots tend to exhibit greater strength but less ductility [108]. STZs are also tightly interlinked with the atomistic potential energy landscape of MGs. There is disorder in glasses at the atomic scale. When that happens, the atoms become disorganized without long-range order, giving rise to a complex energy landscape with many local minima [115]. STZs and atomistic potential energy landscapes are linked due to the fact that local energies surrounding an STZ can have an influence on its behavior, specifically its stability. A local energy landscape’s effect can determine if shear deformation occurs or not and calculate required activation energy versus released shear deformation energy. MD simulations can offer insight into MGs’ energy landscape; alternatively this space can also be probed experimentally using techniques like differential scanning calorimetry and x-ray diffraction [116]. Investigating the formation of soft spots, shear bands and STZs is crucial for developing a deeper understanding of deformation mechanisms present within MGs—this knowledge allows designers to design new MGs with improved mechanical properties.

MD simulations of structure–property correlations in MGs

MGs, due to their disordered state, exhibit a variety of unique mechanical and viscoelastic properties, including high specific strength, high fracture toughness, wear and corrosion resistance. Unlike crystals, the deformation behavior of MGs has been insufficiently understood at both spatial and temporal scales under various loading conditions. To investigate the deformation behavior, MD simulations have been widely employed in recent years to explore the relationships between structure and properties in MGs [79, 117, 118]. The following subsection aims to offer detailed insights into recent advancements and scientific challenges related to the atomic mechanisms underlying the mechanical properties, relaxation, and viscoelastic behavior of MGs.

Mechanical properties of MGs

The mechanical properties of MGs are of significant interest for numerous structural applications. During the deformation of MGs, several atomistic mechanisms play crucial roles, such as shear transformation zones (STZs), shear band formation, free volume generation, local atomic rearrangements and MRO evolution. Typically, MGs exhibit initial elastic deformation followed by limited plasticity and strain softening. In contrast to crystalline materials, where elastic extensions are reversible, MGs undergo irreversible elastic deformation due to atomistic-scale structural rearrangements that result in the generation of free volume [119, 120]. The formation of free volume generally increases with rising shear stress, which is directly correlated with the local atomic packing density characterized by SRO [121]. Later, the presence of MRO has been recognized as critical structural features that significantly influence the mechanical properties of MGs [117, 122]. More precisely, MRO formed by Inter Penetrating Corrections of Icosahedra (ICOI), a specific linkage of icosahedra which is the most stable polyhedral configuration, has the most significant influence on the mechanical properties of MGs. ICOI regions, characterized by their stable structure and low mobility, inhibit the formation of new STZs crucial for plastic flow, thereby increasing resistance to shear deformation. In contrast, MRO regions outside of ICOI are loosely packed and more prone to deformation [122]. This localization of strain flow in pre-deformed areas (shear bands) restricts the dissipation of deformation, concentrating it in specific regions [123]. For instance, Pu et al. studied the compression behavior of \(Mg_{65}Cu_{25}Y_{10}\) MGs, emphasizing the influence of MRO nanoclusters on their deformation [117]. Likewise, Lee et al. suggested that the plasticity of MGs is related to atomic packing density, highlighting the role of SRO atomic clusters in generating free volume during shear deformation [123]. Complex structures like that of MG always poses the challenge in finding these SRO and MRO clusters. Given this predicament, Ronhovde et al. [124] in their article mentioned about such computational techniques to characterize MG like complex structures.

Beyond the elastic limit, the limited ductility before failure in MGs is associated with the formation of STZs and vortex field under the applied load, as shown in Fig. 4(b, c) [125]. These STZs involve irreversible atomic rearrangements that lead to the formation of highly localized shear bands [126]. The formation of localized shear bands leads to brittle failure in MGs without noticeable global plastic deformation [109]. Under specific loading rates, temperature or specific geometry, etc. the stress–strain behavior of MGs can show serrated and non-serrated flow behavior leading to jerky and smooth stress–strain curve. Although the concept and underlying mechanisms of STZs and shear bands are still being investigated, many deformation characteristics and dynamics of MGs, which are correlated with their mechanical properties are explained using the STZ framework. Shimizu et al., using the Aged Rejuvenation Glue Liquid (ARGL) model, elucidated the conditions necessary for stress propagation in MG materials. They introduced the concept of embryonic shear bands (ESBs), which form under applied stress, highlighting the importance of parameters such as long aspect ratio and far-field shear stress, which must exceed a certain threshold [127]. Recent computational studies on parameters related to STZs and shear bands genesis and dynamics has enhanced our understanding of this subject. For example, Samiri et al. used MD simulations to investigate the structural and mechanical properties of Mg-Al MGs. They examined the effects of composition, strain rate, temperature, and annealing on mechanical behavior. Their study revealed that maximum stress increases with higher Al composition, and yield strength rises with increased strain rate [79]. Similarly, Shahzad et al. utilized MD simulations to explore the mechanical properties of Al-Cu-Ni based MGs, with a specific focus on their uniaxial tensile strength across different strain rates. Their findings indicated a significant increase in the mechanical properties of the MGs with higher concentrations of Al, Co, and Ni, including yield strength, Young’s modulus, and ultimate tensile strength [128]. Jiang et al. studied the effect of temperature on MGs and found that increasing temperature deteriorates their mechanical properties while promoting the formation of STZs. Several MD studies focus on enhancing the ductility of MGs. For instance, Zhou et al. explore the tunable tensile ductility of MGs with partially rejuvenated amorphous structures using large-scale atomistic simulations. By increasing both the volume fraction and structural disordering of gradient rejuvenated amorphous structures (GRASs), they enhance the tensile ductility of MGs, inducing a brittle-to-ductile transition in deformation behavior, albeit with some compromise in strength. The critical volume fraction needed to trigger this transition depends on the level of structural disordering. This structural state-dependent transition is explained from a mechanical perspective, considering the competition between macroscopic yield strength and the critical stress required for shear delocalization. They develop a criterion to predict this transition boundary across various structural states in MGs with GRASs, offering insights for designing MGs with tailored combinations of ductility and strength [129]. Zhou et al. use MD simulations to investigate the tensile deformation behaviors of nanoporous MGs containing elliptical and circular pores. The study examines how pore aspect ratio and porosity affect the failure strains of these porous MGs. They observe that increasing the aspect ratio initially enhances the failure strain to a maximum before it decreases. Moreover, for a constant aspect ratio, reducing the porosity increases the failure strain of the nanoporous MGs. These findings suggest that strategically introducing pores can potentially enhance the ductility of MGs [130]. Zhao et al. explore the impact of pre-stress on the mechanical behavior, deformation characteristics, and morphology of shear band formation in \(Cu_{64}Zr_{36}\) MG using MD simulations. Their findings demonstrate that pre-tensile stress diminishes the mechanical performance of the MG, whereas pre-compressive strain induces a transition from hardening to weakening effects. This suggests that both the initial stress state and structural changes induced by applied stress play crucial roles in determining the hardening or weakening behaviors observed in the material [131].

High-strain rate behavior of MGs

Materials subjected to extreme conditions frequently experience deformation at high strain rates (\(10^{5}-10^{8} s^{-1}\)) in scenarios such as high-speed debris impacts, explosions, and high-speed shock loading. Owing to the diverse attractive properties of MG, including high strength, it is important to understand the dynamic behavior of MGs under high-strain rate deformation conditions. In this section, we will discuss recent advancements in understanding the dynamic behavior of MGs under micro-ballistic impact and shock loading.

Micro-ballistic studies are frequently conducted using Laser-Induced Projectile Impact Testing (LIPIT) through experimental methods. This involves launching a micron-sized projectile at the material film at varying speeds [132]. Due to size and computational limitations, the micro-ballistic study in MD is conducted by impacting a nanoscale projectile onto a nanometer-thick film. Dong et al. [133] performed LIPIT experiments on \(Ni_{60}Ta_{40}\) MG nanofilms, varying the impact velocities to investigate their impact resistant behavior.They analyzed the specific penetration energy (\(E_p^{*}\)), which represents the change in the kinetic energy of the projectile normalized by the mass of the film across impact velocities ranging from 186 to 540 m/s. At impact velocities of 300 and 400 m/s, the \(E_p^{*}\) closely matched that of armor-grade Kevlar [134] The MG nanofilm dissipated impact energy through mechanisms such as shear banding, cracking, and bending of cracking-induced petals, depending on the specific impact velocity [133]. Cheng et al. employed LIPIT and MD techniques to investigate the \(Ni_2Ta\) MG films, emphasizing the dynamic size effects of amorphous films, as exhibited in Fig. 4(d). Their study revealed that impact resistance increased with higher impact velocities and thinner film thicknesses. Thinner MG films exhibited enhanced strength and ductility attributed to reduced internal defects and higher surface energy. These characteristics contributed to superior strength and increased plasticity at smaller length scales, resulting in significant impact resistance behavior. A developed scaling law accurately predicts this size-dependent resistance for MGs, thus providing a method for predicting and fabricating high-performance amorphous alloy films [135].

Materials often fail due to the propagation of stress waves, which causes high stress and results in spallation. Ideal shock deformation occurs when a piston-driven shock wave suddenly increases the stress from zero at a specific point. The stress remains constant until the piston is released, symbolizing the release of the shock. After the release, stress levels gradually decrease to zero. However, real-time shock deformation is more complex, being non-ideal and influenced by many factors. Determining mechanical and physical properties during non-ideal deformation requires several sophisticated techniques. In reality, the process is complex because the response gradually increases or decreases once a critical stress threshold is reached. At this point, the material transitions into a state of irreversible plastic deformation rather than remaining in the elastic regime. This critical stress threshold is known as the Hugoniot elastic limit (HEL). As stress continues to rise, it reaches its maximum at what is known as the Hugoniot state. Shock release is associated with a decrease in stress over time. Additionally, dynamic tension produced by reflection from a material’s surface can significantly impact the material, including the creation of micro-voids in its structure, potentially leading to material fracture [136].

In MD, the dynamic behavior of materials under shock is studied using Non-Equilibrium MD (NEMD) and Equilibrium MD (EMD) methods [118]. In NEMD, a shock wave can be generated either by using a piston, known as the piston method, or by pushing the material toward a reflective wall, known as the momentum mirror method. The material being studied is modeled as a long slab in the direction of shock propagation. The Rankine-Hugoniot relationship is applied to examine the relationship between physical and thermodynamic variables. NEMD methods offer a clear view of shock wave propagation and its interaction with materials. These methods effectively visualize the intricate interplay of waves that can result in material failure. However, In EMD, also known as Hugoniostat, the state of the compressed material behind the shock front is simulated without explicitly tracking the motion of the shock wave. This method applies thermodynamic conditions characteristic of shock to a small computational cell. Consequently, EMD does not directly simulate the propagation of shock waves within the material. The method simulates the final state of the shocked material using Hugoniots’ conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy. Hugoniostat methods can be categorized into two types: (a) Uniaxial constant-volume Hugoniostat, which restricts the system’s volume, [137] and (b) Uniaxial constant stress Hugoniostat, which applies a constant stress constraint to the shock wave [138]. In contrast, Multi-Scale Shock Technique (MSST) is an EMD simulation method that derives its foundation from theoretical 1D Euler Equations for compressible flow. It regulates simulation data by iteratively adjusting volume and temperature [141]. This technique is effective when the simulation cell is relatively small and the changes in shocked properties are not too extreme compared to the system at rest. One advantage of the MSST method is its ability to transition the system along the Rayleigh line to a shocked state. Another benefit is the ease and feasibility of simulating the system and obtaining critical steady-state properties such as particle velocities, stresses, and temperatures [139].

(a) Illustration depicting formation of STZs. Reproduced from Refs. 93, 140 with permission. (b) Shear band dynamics under loading in \(Cu_{64}Zr_{36}\) MG. Reproduced from Ref. 125 with permission. (c) Schematic representation of the STZ percolation mechanism. Reproduced from Ref. 125 with permission. (d) Microballisitc impact MD simulation of NiTa MG. Reproduced from Ref. 135 with permission. (e) Schematic representation of shock propagation in the material. Reproduced from Ref. 118, 136 with permission. (f) SRO and MRO in \(Cu_{46}Zr_{54}\) MGs under shock compression. Reproduced from Ref. 141 with permission. (g) Deformation map of \(Cu_{50}Zr_{50}\) Bulk MG under shock compression. Reproduced from Ref. 142 with permission.

The dynamic behavior of MGs under shock loading has been extensively investigated through both experimental studies and MD simulations. While MGs have not been extensively studied for shock loading, CuZr MGs have attracted significant attention in recent years. Jian et al. studied the SRO and MROs in \(Cu_{46}Zr_{54}\) MG. They observed an initial increase in icosahedral structures and their networks up to a critical shock pressure of 60 GPa, accompanied by a reduction in free volume and reversible changes in SRO. At higher shock strengths, the icosahedral network melted and disintegrated, leading to an increase in free volume, depicted in Fig. 4(g) [141]. Demaske et al. conducted additional investigations into the microstructural changes occurring in CuZr MGs. They identified that STZ constituted the primary mechanism of plastic deformation, which intensified with higher shock intensities. Moreover, MGs with higher copper content demonstrated increased shear strengths. The most stable polyhedral type under shock compression was identified as Cu-centered full icosahedra. Wen et al. investigated the influence of initial temperature on the shock response of \(Cu_{50}Zr_{50}\) using MSST technique. The study demonstrated a dependence of the shock Hugoniot relationship on temperature, revealing that shock velocity and critical shear stress decrease with increasing temperature as shown in Fig. 4(g) [142]. In another aspect, Song et al. studied the role of voids in the form of nanopores in \(Cu_{50}Zr_{50}\) MG. The study also illustrated how pore shape influences plastic deformation, showing that ellipsoidal pores oriented vertically exhibit more significant plastic deformation compared to spherical and horizontally oriented ellipsoidal pores. The collapse of voids was observed to occur perpendicular to the direction of shock loading, primarily due to stress concentration at the upper and lower edges of the voids [143].

Relaxations in MGs

Relaxation mechanisms in amorphous materials directly influence the properties thus making it pertinent to understand their influence [144]. They are also related to several crucial unresolved issues in glassy physics [145]. However, formulating a relaxation mechanism for glasses is a complex process [146]. There is tentative evidence that glass exhibits diverse relaxation dynamics over various temperatures and timescales, thus making it difficult to putting forward a standard mechanism [144]. For instance, MGs, even those structurally simplest (compared to molecular or polymeric glasses), can show multiple relaxations, like \(\alpha\) relaxation, \(\beta\) relaxation, fast \(\beta\) relaxation, Boson peak dynamics, a low-temperature relaxation peak (LTP), and nearly constant loss (NCL), [80, 147,148,149] indicating a much richer relaxation scenario than expected [150]. Figure 5(a-b) illustrates the spectrum of relaxation dynamics of glass-forming liquids. The non-equilibrium \(\alpha\) relaxation mechanism, considered disprovable for several years, has also been shown to split into two processes during a deep glassy state during stress relaxation experiments [151].