Abstract

Raman spectroscopy is used to elucidate the effect of spinning conditions upon the structure and mechanical properties of silk spun by Nephila spiders from the major ampullate gland. Silk fibers produced under natural spinning conditions with spinning rates between 2 and 20 mm s−1 differed in microstructure and mechanical properties from fibers produced either more slowly or more rapidly. The data support the “uniform strain” hypothesis that the reinforcing units in spider silk fibers are subjected to the same strain as the fiber, to optimize the toughness. In contrast, in the case of synthetic high-performance polymer fibers, the both units and the fiber experience uniform stress, which maximizes stiffness. The comparison of Nephila major and minor ampullate silks opens an intriguing window into dragline silk evolution and the first evidence of significant differences between the two silks providing possibilities for further testing of hypotheses concerning the uniform strain versus uniform stress models.

Impact statement

It is well established that the microstructure and mechanical properties of engineering materials are controlled by the conditions employed to both synthesize and process them. Herein, we demonstrate that the situation is similar for a natural material, namely spider silk. We show that for a spider that normally produces silk at a reeling speed of between 2 and 20 mm s−1, silk produced at speeds outside this natural processing window has a different microstructure that leads to inferior tensile properties. Moreover, we also show that the silk has a generic microstructure that is optimized to respond mechanically to deformation such that the crystals in the fibers are deformed under conditions of uniform strain. This is different from high-performance synthetic polymer fibers where the microstructure is optimized such that crystals within the fibers are subjected to uniform stress.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spiders make diverse and extensive use of silks typically synthesizing and spinning silks from up to six different types of glands and associated spinnerets.1 Each of these fibers has a specific purpose probably linked to dedicated sets of amino acid compositions, processing conditions, and subsequent mechanical properties.2,3,4,5,6

Most studies investigating structure–property relationships in spider silks concentrate on dragline silks secreted from the set of two major ampullate MaA glands generally because the large size of the gland and the thickness of the filaments make it the easiest silk to handle and investigate in detail.4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Moreover, this silk also displays well the rare characteristics of combined strength and elasticity (toughness) and torsional memory that make it such an interesting material.17,18,19,20 In addition to the MaA fibers, a spider often uses accessory MiA fibers produced in the set of two minor ampullate glands that seem to serve the purpose of reinforcing not only the dragline fibers, but also the threads of the frame and radials of the orb web.21 It is sometimes assumed that the minor ampullate silks are smaller in diameter as they act as support threads to web threads rather than the principal safety line that needs to carry the whole weight of the spider.22 Both major MaA and minor MiA silks were investigated in this study, but the focus of the study was to elucidate the response of the Raman spectra of the different filaments under controlled deformation.

Raman spectroscopy has been employed in a number of studies of silks, both spider23 and silkworm.24,25,26,27,28 It has been used both as a characterization technique and as a means to study differences in secondary conformation between films, powders, and fibers,29,30,31,32,33,34 the denaturation process35,36, and the effect of solvent on fibers.37 Clearly, it is an important tool when studying structural differences.36,38

The assignment of Raman bands for spider silk has followed from the results of studies on silkworm silks. The main difference with spider silk is seen in the C–C backbone vibration found at approximately 1085 cm−1 in silkworm silk, but in the MaA spider silk spectra, it appears consistently at approximately 1095 cm−1.39,40 Using the analogy of model polypeptides and silkworm silk, it is not unreasonable to assign this 1095 cm−1 band to the β-sheet portion of the C–C backbone although there may be contributions from other secondary structures.23

Quantitative Raman techniques have been used to estimate the antiparallel β-sheet content of spider silk to be 22 ± 5%.31 Less β-sheet structure was found in all spider dragline silks than in the Bombyx mori silkworm silk studied by Shao et al.23 with difference between the two taxa that is perfectly in line with current x-ray diffraction data.41

Raman polarization techniques have been employed to study the orientation of crystallites along the fiber axis. The amide I C = O vibration is oriented normally to the fiber axis; therefore, the signal is strongest when scattered perpendicular to the chain axis. The amide III C–N vibration is oriented along the axis and the signal is strongest when excited parallel to the fiber axis. These studies have confirmed that the β-sheet and a small amount of α-helix are highly oriented along the fiber axis, whereas the disordered phase is not preferentially aligned.31

Young et al.39,42 have followed the deformation of both B. mori and Nephila edulis silk fibers using Raman spectroscopy, including a study that examined their behavior under cyclic loading. They found that the 1095 cm−1 peak in spider silk and the 1085 cm−1 band in silkworm silk, assigned to the C–C backbone vibrations,43,44,45 each behave in a similar manner to bands in other high-performance polymer fibers. They also found the amide III band at approximately 1230 cm−1 to shift linearly with stress.39,40,42 The observations led Young et al.39,42 to suggest that it is the polypeptide backbone that takes the strain when the silk is loaded. They also suggested tentatively, based upon their limited data, that the deformation behavior might be consistent with a uniform stress series model. More recently, Kremer et al.46,47,48 demonstrated that the deformation of spider silk can also be followed using fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. This can only be done on bundles of fibers rather than the individual filaments employed for Raman spectroscopy, but analogous shifts of IR bands with stress are obtained. They also found that the shift of the 964 cm−1 IR band with stress was approximately linear, but nevertheless suggested that a pure uniform stress series model would be an oversimplification for this material.

Results

Morphology

Micrographs of the major and minor ampullate silks of the N. senegalensis spider reeled under different conditions (Figure 1) are shown in Figure 2.

Micrographs of N. senegalensis dragline thread. (a) Light microscopy of section of a typical dragline composite thread as reeled with the thicker major and the thinner minor ampullate filaments after gently breathing onto it to demonstrate how humidity causes contraction (partial super-contraction) of the major filaments, but not the minor filaments, which are slack and buckle outward. In both cases, the threads were reeled at the natural walking and frame/radial drawing speeds of 25 mms−1. (b) Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a section of such a thread showing the significant size differences. Lower panels are SEM micrographs of sections of N. senegalensis major ampullate filament reeled slowly (c) at 0.5 mms−1 and fast (d) at 128.6 mms−1.

Reeling speed has a marked effect upon filament diameter and our data agree with the results of an in-depth study of the interaction of spinning speed and temperature by others.49 Indeed, the sample reeled at 128.6 mms−1 is almost half the diameter of the silks reeled at the natural reeling speed ranging between approximately 2 mms−1 and 20 mms−1 [Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material (SM)]. Not entirely a surprise, the high reeling speed created small fluctuations in filament diameter presumably brought about by the high-speed conditions being too fast for the spider to control the diameter.49 Importantly, varying the reeling speed allows us to probe the effects of pultrusion conditions as demonstrated earlier by x-ray scattering,50 birefringence,51 and DMTA.52 Here, we use Raman spectroscopy to probe the system further.

Mechanical properties

While the spinning conditions affect the gross morphology of a filament, they also affect the fine morphology of the silk on the molecular level,50 which manifests itself in the mechanical properties of the fibers that we can measure directly (Table I).

Figure 3 shows a typical stress–strain curve for N. senegalensis major and minor ampullate silk filaments. The force–elongation response is almost linear and nearly identical for both silks in the first 2% of the stress–strain curves, which gives us the initial Young’s modulus. While both silks display similar modulus values, the stress at break of the MiA silk is lower than that for the MaA silk, although the strain to failure is higher for the MiA silk than for the MaA silk (Figure 3a). Thus, both silks will have similar values of toughness (i.e., the ability to absorb energy [given by the area under each stress–strain curve]) albeit using rather different fundamental processes. Although both types of fiber have a similar toughness, the MiA silk appears to undergo a more distinct yield process, presumably to optimize its mechanical functionality in the dragline and web. The difference in toughening mechanisms for the two fibers is probably due to the differences in chemical structure (i.e., the amino acid composition). The crystalline poly-ala interactions silk that contribute to the overall strength of the MaA silk are interrupted in the MiA silk by serine spacer regions, while MiA silks also have an increased glycine content.53,54

Representative stress–strain curves obtained for N. senegalensis major (black) and minor (red) ampullate silks collected at natural reeling speed from one representative animal. (a) Stress and strain at breaking with average data for five samples for each type of silk: Initial modulus (GPa x± SD): MaA: 8.4 ± 1.7 MiA: 8.2 ± 0.6; tensile strength (GPa): MaA: 0.7 ± 0.1, MiA: 0.4 ± 0.1; Load at break (N) MaA: 0.130 ± 0.003, MiA: 0.004 ± 0.001; strain at break (%): MaA: 19.6 ± 1.7, MiA: 30.5 ± 4.3; (b) Load/unloading/reloading curves for representative filaments of the two silks demonstrating significant underlying differences between them.

Of special interest, here is the distinct and very different behavior pattern of the two silks under repeated stressing and straining shown in Figure 3b [i.e., extension to a strain of 0.17 (a), but well below the breaking point followed by relaxation and then followed by another extension (b)]. The energy absorption (areas enclosed in the loops) is lower for the MiA, but Figure 3a shows that this fiber can be deformed to higher elongations at lower stresses. Hence, both silk fibers have similar potential for energy absorption.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectrum of the N. senegalensis dragline silk was obtained using the near-Infra red, helium/neon, and argon ion lasers. From the Ar+ Raman spectra shown in Figure S2 in the SM, we can see a large fluorescent background that would require an excessive amount of data manipulation before results were ready to be analyzed. This extended treatment of spectra before analysis can introduce unnecessary errors in the intensity and peak position data.

Although the He/Ne laser reduces fluorescence and, therefore, the amount of data manipulation prior to final analysis, the spectrum requires 45 × 60 s spectra and ,therefore, 45 min. in total to collect in a useable form as shown in Figure S2a in the SM. The near-IR laser was found to be the most efficient excitation to use due to the shorter collection time, 60 s and 20 accumulations, and the lack of data manipulation required. This reduces the risk of any damage to the fiber while in the laser light and gives a well-resolved spectrum that cuts down on errors that may be introduced by smoothing spectra and adjusting baselines. Using the near-IR excitation also means that the peaks investigated as part of this study are the most prominent peaks in the silk spectra. The 1095 cm−1 peak is better defined than with the He/Ne laser as are the 1670 cm−1 and 970 cm−1 peaks.

Raman analysis of spider silks is still a developing field23,28,31,36,37,39,42,55,56 and the full assignment and comparison with other fibrous proteins attempted here will aid further investigations into these superior fibrous materials. Figure S2b in the SM shows the near-IR Raman spectrum from 800 to 1800 cm−1. The wavenumbers of the peaks have been labeled and Table S1 in the SM shows the vibrational assignments made for these peaks.

Figure 4a shows a comparison between the silk filaments spun from the major and minor ampullate glands where we were able to detect clear differences. In order to allow for the significant diameter differences, we needed to normalize the intensities to the 1450 cm−1 peak with the smaller diameter MiA filaments making for weaker scattering resulting in a “noisier” signal. The most noticeable real difference in the spectra was between the 830/855 cm−1 doublet. The minor ampullate spectrum had a much larger 855 cm−1 peak indicating a weaker hydrogen bonding environment in this silk that may be responsible for the lower yield stress of the MiA silk (Figure 3). This is confirmed by a decrease in relative intensity of the 1095 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 peaks. It may be of relevance here that the amino acid sequence of Nephila’s minor ampullate silk contains spacer regions, which may account for part of a weaker hydrogen bonding environment.53

A similar issue over signal strength was found for the MaA filaments reeled at extreme speeds (Figure 4b) where there can be a diameter difference of as much as 5 μm (Table I). The particularly small diameter of the faster reeling speed sample made it very difficult to focus the 2-μm laser spot onto a 3-μm fiber, with obvious effects on the signal-to-noise ratio and spectral intensity. Overall, however, the main features of the spectra were similar between all of the MaA silk filaments processed at different spinning speeds, showing that the chemical structure of the silk is controlled by the type of gland used rather than the spinning conditions.

To probe the molecular reconfigurations of Nephila major ampullate silk during deformation, we examined the band shifts of the 970 cm−1, 1095 cm−1, 1230 cm−1, and 1400 cm−1 Raman peaks (Figure S3a–d in the SM) and found that the strain-induced band shifts were indeed nonlinear confirming previous studies.39,42 The stress-induced band shifts of the 1095 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 peaks were reported previously for N. edulis39,40,42 to be approximately linear up to a stress of about 0.8 GPa. There was no report in these studies of the mechanical behavior of the MaA silk at larger values of stress. The loading technique used in this present investigation and the higher strength of the N. senegalensis major ampullate MaA silk has allowed Raman spectra to be obtained at stresses up to 1.8 GPa. We found that the band shifts of the 1095 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 peaks, along with those of peaks at 970 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1, are approximately linear up to around 0.4 GPa, but at larger stresses the rate of band shift with stress decreases as shown in Figure 5. The behavior of the 1095 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 bands was found to be similar. It should also be noted that, for these fibers, the Raman bands show a broadening that has not been quantified in detail as part of this present study, but indicates local stress distributions within the molecules occurring while the fiber is being stressed.42,57

Raman band shifts responding to stressing and straining N. senegalensis major ampullate silk filaments reeled at natural walking speed of 23 mms−1. Analysis of band shifts in response to two key positions in response to two critical stresses. (a) 970 cm−1 Raman band at low stress, (b) 970 cm−1 band at high stress, (c) 1400 cm−1 Raman band at low stress, and (d) 1400 cm−1 band at high stress. (It should be noted that there is some variation in the zero stress values as the result of calibration variations). The lines in the figures are second-order fits to the data to guide the eye.

The linear band shift rates up to 300 MPa from Figure 5 and those of the 1095 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 bands are listed in Table S2 in the SM and they are consistent with previous reports.39,40,42 In particular, the stress-induced shifts of the 970 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1 Raman bands are new observations.

The initial stress-induced band shift rates of the MaA samples reeled at different speeds are shown in Table S3 in the SM. The overall shapes of the curves are similar to the stress-induced band shifts for the natural reeling speed samples. The curves are all linear up to approximately 300 MPa and then become nonlinear. The stress-induced band shift rates are found to be comparable for the 1.9 mms−1, 10.7 mms−1, and 23.1 mms−1 reeling speeds (these speeds are within the normal spinning range of the Nephila spiders49), whereas larger values are found for all Raman bands for the highest and lowest reeling speeds of 0.5 mms−1 and 128.6 mms−1. This implies that although the MaA filaments have the same chemical structure (Figure 4b), their microstructures and mechanical properties appear to depend upon the processing conditions.47,48

Discussion

In order to model and understand the deformation behavior of the spider silks studied, a number of different observations relevant to this present study need to be highlighted.

-

The Raman band shifts are nonlinear with strain.

-

The Raman band shifts are linear with stress up to about 300 MPa and then become nonlinear.

-

The Raman bands broaden with stress.

-

The Raman band shift rates per unit stress depend upon reeling speed and are higher for the highest and lowest reeling speeds.

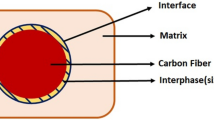

It is well established that high-performance fibers such as PPTA43,44,45,54 and poly(ethylene terephthalate) PET57 have microstructures in which the stress-bearing units are in series (see Figure S4 in the SM). In this situation, during deformation, the stress on the different units in the microstructure of the fiber is the same as the overall fiber stress. This is generally known as the uniform stress series model, which will be considered first.

The analysis of the deformation mechanism in spider silk using Raman spectroscopy has been considered by Brookes et al.58 The starting point in their analysis is that the change in Raman wavenumber, Δν, that occurs during the deformation of high-performance polymer fibers is due to chain stretching and proportional to the stress on the crystalline reinforcing units, σr. This is a well-established relationship that has been demonstrated to be applicable to a number of different types of fibers.45 A similar relationship with stress is also found for the IR bands in spider silk.47 Therefore, for an increment of stress

Since for the uniform stress model the stress is uniform throughout the microstructure, σr equals σf, the fiber stress. Hence, by dividing by an increment of fiber strain, εf, Equation (1) becomes

where Ef is the fiber’s Young’s modulus. Figure S5 in the SM shows for the Raman bands at around 1610 cm−1 literature data on the dependence of dΔν/dεf upon fiber modulus. This is the result of the stretching of the p-phenylene groups in PPTA and PET fibers and the data follow the prediction given by Equation (2). A consequence of this uniform stress series model is that the Raman band shift per unit stress, dΔν/dσf, for the 1610 cm−1 Raman band in PPTA and PET fibers is constant around − 4.0 cm−1/GPa and independent of their Young’s modulus, microstructure, and processing conditions.45

The Raman band shift data for the spider silk fibers in Table S3 in the SM show that the value of dΔν/dσf for each Raman band varies with reeling speed (i.e., processing conditions). As pointed out by Brookes et al.,58 this implies that the uniform stress series model is not appropriate for the MaA spider silk. Other investigators came to a similar conclusion from the analysis of the deformation of silk fibers with simultaneous x-ray diffraction.59 They found that the crystal modulus of the B. mori fibers varied with the degree of crystallinity. Moreover, the classic model of Termonia60 for the mechanical behavior of silk is not a uniform stress model.

In view of these discrepancies, Brookes et al.58 suggested the use of an alternative model, the uniform strain parallel model,Footnote 1 shown in Figure 6a, for which the strain on the reinforcing units, εr, is the same as the overall fiber strain, εf. The assumption of uniform strain leads to

where Er is the Young’s modulus of the reinforcing units. Combining with the general relationship in Equation (1) gives the following relation:

It can be assumed that the modulus of the reinforcement in the fibers, Er, is constant and Ef can be taken as the initial slope of the stress–strain curves of the silk fibers (Table I). Hence the uniform strain model predicts that dΔν/dσf should be proportional to the reciprocal of the modulus of the fiber, 1/Ef. Figure 6b shows a plot of dΔν/dσf as a function of 1/Ef using the data for the 1095 cm−1 Raman band from Tables S2 and S3 in the SM. This band was chosen as it has been assigned to the C–C backbone in the β-sheets that are thought to be the main reinforcing units in the silk.60

The main difference between the model in Figure 6b and the uniform stress model in Figure S4 is that the reinforcing units are not lined up in series. This arrangement of the reinforcing units explains why the stress/strain curves of the spider silk are quite different from those of high-performance polymer fibers. The silk has a lower Young’s modulus, but is very much more extensible, leading to outstanding levels of toughness.61 It also explains why crystal modulus values determined from simultaneous x-ray diffraction and deformation experiments on different types of silk do not agree well with computed values,59,62 unlike similar experiments on PPTA.63 Our previous studies upon stress-induced Raman band shifts in silk39,42 had suggested that the uniform stress model might be applicable. This was based upon limited data and the observation that the shifts were more linear when plotted against stress than against strain, as has been found with PET fibers.57 Our present study has demonstrated that it is necessary to use a range of spider silk fibers processed in different ways (e.g., by varying reeling speed), such that they have different microstructures and mechanical properties, before the behavior can be fully modeled.64,65

It should be pointed out that this modeling is based only upon the analysis of the elastic deformation of the material, but it also provides information upon how the microstructure responds to higher levels of deformation. It is possible to speculate upon how the microstructures will affect the overall toughness of the silk fibers by considering what will happen at high levels of overall strain. In the case of the uniform strain situation (Figure 6a), the strain in the crystals and amorphous regions will be similar. In contrast, in the case of the uniform stress parallel model (Figure S4), the flexible amorphous chains between the crystals will experience high levels of stress leading high local strains and failure at low levels of overall fiber strain. Hence, a fiber microstructure following the uniform strain model such as PPTA will lead to fibers with high levels of stiffness, but low strains to failure. In contrast, a microstructure following the uniform stress model, such as spider silk, will lead to fibers with a lower initial stiffness, but higher levels of strain-to-failure and so higher toughness.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the mechanical properties of spider silk fibers can only be fully understood by analyzing the behavior of silk processed under different conditions. We found that the stress-induced Raman band shifts enabled the behavior to be interpreted in terms of a uniform strain model, which leads fibers with high levels of toughness. The derived model is consistent with earlier observations upon silk fibers using x-ray diffraction. The structure–property relationships in the silk can be contrasted with those of high-performance polymer fibers that can be analyzed in terms of a uniform stress model. This leads to fibers with higher levels of Young’s modulus than spider silk, but much lower levels of toughness. Clearly, spiders have evolved to produce fibers with mechanical properties optimized for applications in their environments where toughness is an essential requirement.

Materials and methods

Spider silk

N. senegalensis spiders (Figure 1a) were reared in controlled conditions in a greenhouse. Webs were sprayed with water every few days, and spiders were fed with flies, Musca domestica for adults and Drosophila for juveniles. The silk samples were obtained from the spiders by natural spinning at around 10 mms−1 and by forced reeling at speeds 0.5 mms−1, 1.9 mms−1, 10.7 mms−1, 23.1 mms−1, and 128 mms−1 from fully awake N. senegalensis spiders using the procedures and apparatus described next.

The spider was restrained using a circular pad and cling film and the spinnerets viewed using an Olympus SZ40 optical microscope with 150 HL universal flexilux light source. The major and minor ampullate silk was collected from the spinneret using tweezers and then separated. The silk to be reeled was then taped to the bobbin and the motor started with the other fibers taped out of the way to avoid mixing of the samples as shown in Figure 1b. All samples were kept at 50 ± 5% humidity and 23 ± 1°C for at least 7 days prior to testing.

Scanning electron microscopy

A Philips field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FEG-SEM) XL30 system operated at 2 kV was used in conjunction with a PC running the standard Philips microscope control software to obtain images of all samples. Specimens of spider silk were prepared by laying single fibers onto an adhesive carbon tab on an aluminum SEM specimen stub. These were then coated with a thin layer of carbon using an Edwards E306A system to avoid charging in the microscope. The SEM and software were calibrated using a standard calibration specimen grid and then used to measure the diameters of spider monofilaments. This enabled the stress values to be calculated when studying fiber deformation. Average diameters were calculated using measurements taken from 10 different fibers of each type, with the diameter of each fiber being measured at 10 different points along its length. The fibers were assumed to have circular cross sections in the determination of fiber cross-sectional area for the calculations of stress.

Mechanical testing

Individual fibers were mounted across cardboard windows using slow setting Araldite epoxy resin. These were then left to set for 7 days at room temperature and kept in an atmosphere controlled at 23 ± 1°C and 50 ± 5% relative humidity for at least 3 days before testing. These cards had fiber gauge lengths of 20 mm, 50 mm, or 100 mm. The fiber-mounted window was placed in the grips of the Instron 1121 universal testing machine and the card on either side of the fiber carefully cut using a burner, to separate the ends. A cross-head speed of 2 mm/min was used for the 20-mm gauge length samples, 5 mm/min for the 50-mm samples, and 10 mm/min for the 100-mm samples. A full-scale load of 10 N was used and a standard weight of 1 N was used to calibrate the instrument prior to and during testing. A minimum of 20 samples per gauge length were tested in controlled conditions of 23 ± 1°C and 50 ± 5% relative humidity. Stress values for each individual fiber were calculated using the diameters investigated using a calibrated SEM.

Raman spectroscopy

A Renishaw 1000 Raman microprobe system was used to study the samples. Low power (> 25 mW) near-infrared, helium/neon, and argon ion laser light sources of wavelengths 785, 633, and 514 nm were employed. The near-infrared laser was found to be the most efficient for use in the analysis of the spider silk. This lower energy laser reduces the fluorescence/luminescence often seen with natural fiber samples and therefore helps to gain a better-defined spectrum. The specimens were viewed using an Olympus BH-2 optical microscope with the laser focused to a spot of approximately 2 μm on the surface of the sample by means of a 50 × microscope objective lens with a 0.65-mm aperture. Exposure times of 60 to 120 s, depending on the luminescence and strength of signal from each sample at full power, were used to obtain well-defined Raman spectra of the samples.

Spectroscopy and deformation

Spectra were obtained using single fiber specimens on fiber cards prepared as described previously.37 These were mounted onto a single fiber stress rig that was connected to a transducer for reading the applied load in grams. The fiber was fixed between the two aluminum blocks using cyanoacrylate adhesive and the card burned as for the tensile testing procedure to leave a fixed gauge length sample. The fibers were deformed stepwise up to failure by moving the block with the attached micrometer, accurate to within ± 0.005 mm. Strain was calculated form the change in fiber length divided by the original gauge length. Spectra were obtained of each fiber using the conditions described previously, with the same exposure time and accumulation number used for each stress value of a particular sample. Stress values were calculated using calibrated SEM diameter measurements and cross-sectional areas calculated for that specific fiber or portion of fiber.

Notes

We note out that this uniform strain parallel model for silk fibers is mathematically similar to the uniform strain Voigt model for a composite with long uniaxially aligned fibers (rule of mixtures). However, a long fiber reinforced composite and silk fibers have quite different microstructures, as shown in Figure 6a, and the only similarity is that the two components in each model are both subject to uniform strain.

References

F. Vollrath, D. Porter, C. Holland, The science of silks. MRS Bull. 38, 73 (2013)

F. Vollrath, D. Porter, C. Holland, There are many more lessons still to be learned from spider silks. Soft Matter 7, 9595 (2011)

C. Guo, C. Li, X. Mu, D.L. Kaplan, Engineering silk materials: From natural spinning to artificial processing. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 011313 (2020)

S.J. Blamires, T.A. Blackledge, I.-M. Tso, Physicochemical property variation in spider silk: Ecology, evolution, and synthetic production. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62, 443 (2017)

D. Ebrahimi, O. Tokareva, N.G. Rim, J.Y. Wong, D.L. Kaplan, M.J. Buehler, Silk–Its mysteries, how it is made, and how it is used. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 1, 864 (2015)

C. Holland, K. Numata, J. Rnjak-Kovacina, F.P. Seib, The biomedical use of silk: Past, present, future. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1800465 (2019)

A.D. Malay, K. Arakawa, K. Numata, Analysis of repetitive amino acid motifs reveals the essential features of spider dragline silk proteins. PLoS ONE 12, e0183397 (2017)

J. Bauer, T. Scheibel, Conformational stability and interplay of helical N- and C-terminal domains with implications on major ampullate spidroin assembly. Biomacromolecules 18, 835 (2017)

J. Bauer, D. Schaal, L. Eisoldt, K. Schweimer, S. Schwarzinger, T. Scheibel, Acidic residues control the dimerization of the N-terminal domain of black widow spiders’ major ampullate spidroin 1. Sci. Rep. 6, 34442 (2016)

S.J. Blamires, C.-P. Liao, C.-K. Chang, Y.-C. Chuang, C.-L. Wu, T.A. Blackledge, H.-S. Sheu, I.-M. Tso, Mechanical performance of spider silk is robust to nutrient-mediated changes in protein composition. Biomacromolecules 16, 1218 (2015)

Y. Liu, A. Sponner, D. Porter, F. Vollrath, Proline and processing of spider silks. Biomacromolecules 9, 116 (2008)

H.C. Craig, D. Piorkowski, S. Nakagawa, M.M. Kasumovic, S.J. Blamires, Meta-analysis reveals materiomic relationships in major ampullate silk across the spider phylogeny. J. R. Soc. Interface 17, 20200471 (2020)

M. Wojcieszak, G. Gouadec, A. Percot, P. Colomban, Micromechanics of fresh and 30-year-old Nephila inaurata madagascariensis dragline silk. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 11759 (2017)

R. Madurga, G.R. Plaza, T.A. Blackledge, G.V. Guinea, M. Elices, J. Pérez-Rigueiro, Material properties of evolutionary diverse spider silks described by variation in a single structural parameter. Sci. Rep. 6, 18991 (2016)

M. Marhabaie, T.C. Leeper, T.A. Blackledge, Protein composition correlates with the mechanical properties of spider (Argiope trifasciata) dragline silk. Biomacromolecules 15, 20 (2014)

S.J. Blamires, C.-L. Wu, T.A. Blackledge, I.-M. Tso, Post-secretion processing influences spider silk performance. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2479 (2012)

D. Porter, J. Guan, F. Vollrath, Spider silk: Super material or thin fibre? Adv. Mater. 25, 1275 (2013)

A. Koeppel, C. Holland, Progress and trends in artificial silk spinning: A systematic review. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 226 (2017)

D. Liu, A. Tarakanova, C.S. Hsu, M. Yu, S. Zheng, L. Yu, J. Liu, Y. He, D.J. Dunstan, M.J. Buehler, Spider dragline silk as torsional actuator driven by humidity. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau9183 (2019)

O. Emile, A. Le Floch, F. Vollrath, Shape memory in spider draglines. Nature 440, 621 (2006)

B. Mortimer, A spider’s vibration landscape: Adaptations to promote vibrational information transfer in orb webs. Integr. Comp. Biol. 59, 1636 (2019)

E.K. Tillinghast, M.A. Townley, “Silk Glands of the Araneid Spiders,” in Silk Polymers, ACS Symposium Series 544, D. Kaplan, W.W. Adams, B. Farmer, C. Viney, Eds. (American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 1994), p. 29

Z. Shao, F. Vollrath, J. Sirichaist, R.J. Young, Analysis of spider silk in native and supercontracted states using Raman spectroscopy. Polymer 40, 2493 (1999)

P. Monti, G. Freddi, A. Bertouzza, N. Kasai, M. Tsukada, Raman spectral studies of silk fibroin. J. Raman Spectrosc. 29, 297 (1995)

P. Monti, P. Taddei, G. Freddi, T. Asakura, M. Tsukada, Raman spectroscopic characterization of Bombyx mori silk fibroin: Raman spectrum of silk I. J. Raman Spectrosc. 32, 103 (2001)

H.G.M. Edwards, D.W. Farwell, Raman spectral studies of silk. J. Raman Spectrosc. 26, 901 (1995)

M.-E. Rousseau, T. Lefèvre, L. Beaulieu, T. Asakura, M. Pézolet, Study of protein conformation and orientation in silkworm and spider silk fibers using Raman microspectroscopy. Biomacromolecules 5, 2247 (2004)

T. Lefèvre, M.-E. Rousseau, M. Pézolet, Protein secondary structure and orientation in silk as revealed by Raman spectromicroscopy. Biophys. J. 92, 2885 (2007)

M. Tsukada, G. Freddi, P. Monti, A. Bertoluzza, N. Kasai, Structure and molecular conformation of tussah silk fibroin films: Effect of methanol. J. Polym. Sci. B 33, 1995 (1995)

P. Monti, G. Freddi, A. Bertoluzza, N. Kasai, M. Tsukada, Raman spectroscopic studies of silk fibroin from Bombyx mori. J. Raman Spectrosc. 29, 297 (1998)

D.B. Gillespie, C. Viney, P. Yager, “Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of the Secondary Structure of Spider Silk Fiber,” in Silk Polymers, ACS Symposium Series 544, D. Kaplan, W.W. Adams, B. Farmer, C. Viney, Eds. (American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 1994), p. 155

P. Colomban, H.M. Dinh, J. Riand, L.C. Prinsloo, B. Mauchamp, Nanomechanics of single silkworm and spider fibres: A Raman and micromechanical in situ study of the conformation change with stress. J. Raman Spectrosc. 39, 1749 (2008)

M. Preghenella, G. Pezzotti, C. Migliaresi, Comparative Raman spectroscopic analysis of orientation in fibers and regenerated films of Bombyx mori silk fibroin. J. Raman Spectrosc. 38, 522 (2007)

M.E. Rousseau, L. Beaulieu, T. Lefèvre, J. Paradis, T. Asakura, M. Pézolet, Characterization by Raman microspectroscopy of the strain-induced conformational transition in fibroin fibers from the silkworm Samia cynthia ricini. Biomacromolecules 7, 2512 (2006)

S. Zheng, G. Li, W. Yao, T. Yu, Raman spectroscopic investigation of the denaturation process of silk fibroin. Appl. Spectrosc. 43, 1269 (1989)

T. Lefèvre, F. Paquet-Mercier, J.-F. Rioux-Dubé, M. Pézolet, Structure of silk by raman spectromicroscopy: From the spinning glands to the fibers. Biopolymers 97, 322 (2012)

Z. Shao, R.J. Young, F. Vollrath, The effect of solvents on spider silk studied by mechanical testing and single fibre Raman spectroscopy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 24, 295 (1999)

K.A. Trabbic, P. Yager, Comparative structural characterization of naturally and synthetically spun fibers of Bombyx mori fibroin. Macromolecules 31, 462 (1998)

J. Sirichaist, R.J. Young, F. Vollrath, Molecular deformation in spider dragline silk subjected to stress. Polymer 41, 1223 (2000)

J. Sirichaist, UMIST, Manchester (2000).

Y. Takahashi, “Crystal Structure of Silk of Bombyx mori,” in Silk Polymers, ACS Symposium Series 544, D. Kaplan, W.W. Adams, B. Farmer, C. Viney, Eds. (American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 1994), p. 169

J. Sirichaist, R.J. Young, F. Vollrath, V. Brookes, Analysis of structure/property relationships in silkworm (Bombyx mori) and spider dragline (Nephila edulis) silks using Raman spectroscopy. Biomacromolecules 4, 387 (2003)

R.J. Young, D. Lu, R.J. Day, Raman spectroscopy of kevlar fibers during deformation caveat emptor. Polym. Int. 24, 71 (1991)

R.J. Young, D. Lu, R.J. Day, W.F. Knoff, H.A. Davis, Relationship between structure and mechanical properties for aramid fibers. J. Mater. Sci. 27, 5431 (1992)

R.J. Young, Monitoring deformation processes in high-performance fibres using Raman spectroscopy. J. Text. Inst. 86, 360 (1995)

A.M. Anton, W. Kossack, C. Gutsche, R. Figuli (Ene), P. Papadopoulos, J. Ebad-Allah, C. Kuntscher, F. Kremer, Pressure-dependent FTIR-spectroscopy on the counterbalance between external and internal constraints in spider silk of Nephila pilipes. Macromolecules 46, 4919 (2013)

R. Ene, P. Papadopoulos, F. Kremer, Combined structural model of spider dragline silk. Soft Matter 5, 4568 (2009)

P. Papadopoulos, J. Sölter, F. Kremer, Hierarchies in the structural organization of spider silk—A quantitative model. Colloid Polym. Sci. 287, 231 (2008)

F. Vollrath, B. Madsen, Z.Z. Shao, The effect of spinning conditions on the mechanics of a spider’s dragline silk. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 268, 2339 (2001)

C. Riekel, B. Madsen, D. Knight, F. Vollrath, X-ray diffraction on spider silk during controlled extrusion under a synchrotron radiation x-ray beam. Biomacromolecules 1, 622 (2000)

C. Holland, K. O’Neil, F. Vollrath, C. Dicko, Distinct structural and optical regimes in natural silk spinning. Biopolymers 97, 368 (2012)

B. Mortimer, J. Guan, C. Holland, D. Porter, F. Vollrath, Linking naturally and unnaturally spun silks through the forced reeling of Bombyx mori. Acta Biomater. 11, 247 (2015)

M.A. Colgin, R.V. Lewis, Spider minor ampullate silk proteins contain new repetitive sequences and highly conserved non-silk-like “spacer regions.” Protein Sci. 7, 667 (1998)

C.Y. Hayashi, N.H. Shipley, R.V. Lewis, Hypotheses that correlate the sequence, structure, and mechanical properties of spider silk proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 24, 271 (1999)

J. Dionne, T. Lefèvre, P. Bilodeau, M. Lamarre, M. Auger, A quantitative analysis of the supercontraction-induced molecular disorientation of major ampullate spider silk. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 31487 (2017)

M. Gauthier, J. Leclerc, T. Lefèvre, S.M. Gagné, M. Auger, Effect of pH on the structure of the recombinant C-terminal domain of Nephila clavipes dragline silk protein. Biomacromolecules 15, 4447 (2014)

W.Y. Yeh, R.J. Young, Molecular deformation processes in aromatic high modulus polymer fibres. Polymer 40, 857 (1999)

V.L. Brookes, R.J. Young, F. Vollrath, Deformation micromechanics of spider silk. J. Mater. Sci. 43, 3728 (2008)

A. Sinsawat, S. Putthanarat, Y. Magoshi, R. Pachter, R.K. Eby, X-ray diffraction and computational studies of the modulus of silk (Bombyx mori). Polymer 43, 1323 (2002)

Y. Termonia, Molecular modeling of spider silk elasticity. Macromolecules 27, 7378 (1994)

F. Vollrath, D. Porter, Spider silk as a model biomaterial. Appl. Phys. A 82, 205 (2005)

T. Nishino, K. Nakamae, Elastic modulus of the crystalline regions of Tussah silk. Polymer 33, 1328 (1992)

M.A. Montes-Moran, R.J. Davies, C. Riekel, R.J. Young, Deformation studies of single rigid-rod polymer-based fibres, Part 1, Determination of crystal modulus. Polymer 43, 5219 (2002)

F. Fraternali, N. Stehling, A. Amendola, B.A. Tiban Anrango, C. Holland, C. Rodenburg, Tensegrity modelling and the high toughness of spider dragline silk. Nanomaterials 10, 1510 (2020)

D. López Barreiro, J. Yeo, A. Tarakanova, F.J. Martin-Martinez, M.J. Buehler, Multiscale modeling of silk and silk-based biomaterials—A review. Macromol. Biosci. 19, 1800253 (2019)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to V.L. Brookes for undertaking some of the experimental investigations reported in this study. We thank the UK Research and Innovation Council, the Royal Society, the Natural Science Foundation of China, the European Research Council, the EU-Horizon 2020 Program and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research for funding our research and collaborations over the years, including this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, R.J., Holland, C., Shao, Z. et al. Spinning conditions affect structure and properties of Nephila spider silk. MRS Bulletin 46, 915–924 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-021-00194-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-021-00194-1