Abstract

Background

Due to an ageing demographic and rapid increase of cognitive impairment and dementia, combined with potential disease-modifying drugs and other interventions in the pipeline, there is a need for the development of accurate, accessible and efficient cognitive screening instruments, focused on early-stage detection of neurodegenerative disorders.

Objective

In this proof of concept report, we examine the validity of a newly developed digital cognitive test, the Geras Solutions Cognitive Test (GCST) and compare its accuracy against the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

Methods

106 patients, referred to the memory clinic, Karolinska University Hospital, due to memory complaints were included. All patients were assessed for presence of neurodegenerative disorder in accordance with standard investigative procedures. 66% were diagnosed with subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), 25% with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 9% fulfilled criteria for dementia. All patients were administered both MoCA and GSCT. Descriptive statistics and specificity, sensitivity and ROC curves were established for both test.

Results

Mean score differed significantly between all diagnostic subgroups for both GSCT and MoCA (p<0.05). GSCT total test time differed significantly between all diagnostic subgroups (p<0.05). Overall, MoCA showed a sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.54 at a cut-off of <=26 while GSCT displayed 0.91 and 0.55 in sensitivity and specificity respectively at a cutoff of <=45.

Conclusion

This report suggests that GSCT is a viable cognitive screening instrument for both MCI and dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dementia is currently a global driver of health care costs, and with an ageing demographic, the disease burden of neurodegenerative disorders will increase exponentially in the future. The prevalence is estimated to double every two decades, reaching approximately 80 million affected patients worldwide in 2030 (1). In 2016, the global costs associated with dementia were 948 billion US dollars and are currently projected to increase to 2 trillion US dollars by 2030, corresponding to roughly 2% of the world’s total current gross domestic product (GDP) (2, 3)..

Dementia, or major neurocognitive disorder (MCD), is an umbrella term for neurodegenerative disorders typically characterized by memory dysfunction with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) constituting approximately 60% of all cases. Other common forms of dementia include vascular dementia, Lewy-Body dementia and Frontotemporal dementia. Modern diagnostic tools, such as various imaging modalities and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (4, 5), have improved our diagnostic accuracy substantially. These methods have also provided key insights into the pathological mechanisms associated with neurodegenerative and contributed to the development of concepts such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and “preclinical AD” (6, 7). Preclinical AD is defined by the presence of cerebral amyloid or tau pathology, identified by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, before the onset of clinical symptoms (8).

Nevertheless, assessment of cognitive functions, the primary clinical outcome of interest, still largely relies on analogue “pen and paper” based tests administered to patients by health care providers (9). Although some regional differences exist, two of the most known and used cognitive tests include the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (10, 11). Both tests assess various cognitive domains, with some inter-test differences, including for example; orientation, memory, concentration, executive functions, language, and visuospatial abilities (9) with scores ranging from 0 to 30 points. MoCA, as compared to MMSE which is mostly focused on memory deficits, includes assessment of more cognitive domains thus increasing its diagnostic accuracy. Although optimal cut-off points vary somewhat between different studies, a score lower than 26 on MoCA and 24 on MMSE are considered indicative of dementia (12–15). MoCA has in a previous meta-analysis shown to have a sensitivity and specificity of 0.94 and 0.60 respectively, at a cut-off of 26 points (16). This indicates a good ability to detect dementia, but at the cost of a high amount of false positives. MMSE has, in a meta-analysis, demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.9 (14). However, MMSE has limited value in detecting MCI and prodromal AD patients from healthy controls (17). Albeit, in the setting of cognitive screening tests a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity is necessary and screening instruments should favor sensitivity over specificity.

Given the current scientific consensus that potential future disease-modifying drugs for AD need to be administered early on in the disease continuum, there is a clear need to develop accurate and widely available cognitive screening tests in order to facilitate early diagnosis of MCI patients in the future. In the European Union, there are currently approximately 20 million individuals over the age of 55 with MCI, most of whom have not undergone screening for cognitive impairment (18). A previous study investigating the treatment and diagnostic capacity of six European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom) estimated that over 1 million patients would progress from MCI to AD due to capacity constraints within current health care systems if a disease modifying treatment were to be available in 2020 (18). As such, digital cognitive screening instruments are likely to be a part of the diagnostic process in the future, especially when considering the advancement of digitalized health care in multiple facets of modern medicine (19).

Cognitive assessment instruments are available in different settings including clinic based and at home testing (20, 21). Current cognitive evaluation methods include both pen-and-paper screening tools, which is the conventional method administrated by a clinical neuropsychologist, and computerized cognitive tests (20, 21). Increasing advances in technology has led clinical trials to move away from the conventional methods and adopt validated digital cognitive tools that are sensitive to capturing cognitive changes in early prevention stages (20, 22). Computerized cognitive assessment tools offer several benefits over the traditional instruments, enabling recording of accuracy and speed of response precisely, minimizing floor and ceiling effects and eliminating the examiner bias by offering a standardized format (20–22). Computerized cognitive assessments may also generate potential time and cost savings as the test can be administrated by the patient or other healthcare professionals than neuropsychologist, as long as appropriate professional will be responsible for the test interpretation and diagnosis (20, 22). Thus, unmonitored digital tools provide practical advantages of reduced need for trained professionals, self-administration, automated test scoring and reporting and ease of repeat adjustments, which enable administration for large-scale screening (22, 23). On the other hand, cognitive assessment tools are typically administrated to elderly population who might lack familiarity with digital tools, which can negatively affect their performance (22, 24). However, the attitude and perception of patients using a computerized cognitive assessment have been investigated in the elderly population, and individuals expressed a growing acceptance of using computerized cognitive assessments and rated them as understandable, easy to use and more acceptable than pen and paper tests (20, 22). They also perceived them as having the potential to improve patient care quality and the relationship between the patient and clinician when human intervention is involved (20).

Currently, there are a number of computerized screening instruments available, and they are either a digital version of the existing standardized tests or new computerized tests and batteries for cognitive function assessment (25). The pen-and-paper version of the MoCA test was recently transformed to an electronic version (eMoCA) (24). eMoCA was tested on a group of adults to compare its performance to MoCA, and most of the subjects performed comparably (24). For the detection of MCI, eMoCA (24, 25) and CogState (26) showed promising psychometric properties (25). Computer test of Inoue (27), CogState (26) and CANS-MCI (28) showed a good sensitivity in detecting AD (25). Unlike the other computerized cognitive screening tools, Geras Solutions is a comprehensive tool that provides, besides the cognitive test, a medical history questionnaire that is administrated by the patient, and a symptom survey that is administrated by the patient’s relatives. Thus, it has the potential to save more time and cost compared to the other digital assessment instruments by providing a more complete clinical evaluation.

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the accuracy and validity of a newly developed digital cognitive test (Geras Solutions Cognitive Test [GSCT]). The GSCT is a self-administered cognitive screening test provided by Geras Solutions predominantly based on MoCA. In this study, we intend to investigate the validity of GSCT, including psychometric properties, agreement with MoCA and diagnostic accuracy by establishing sensitivity, specificity, receiver operating characteristics (ROC), area under the curve values (AUC) and optimal cut-off levels, as well as compare performance with MoCA.

Materials and methods

Geras Solutions cognitive test

The GSCT, is a newly developed digital screening tool for cognitive impairment and is included in the Geras Solutions APP (GSA). Development of the screening tool was done in collaboration with the research and clinical team at Theme Aging, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna memory clinic and Karolinska Institutet. GSCT is developed on existing cognitive assessment methods (MoCA and MMSE) and includes additional proprietary tests developed at the memory clinic, Karolinska University Hospital Stockholm, Sweden. The test is suitable for digital administration through devices supporting iOS and Android.

The test is composed of 16 different items assessing various aspects of cognition, developed in order to screen for cognitive deterioration in the setting of dementia and to ensure suitability for administration via mobile devices. The GSCT is scored between 0–59 points in total and has six main subdomains including; memory (0–10 points), visuospatial abilities (0–11 points), executive functions (0–13 points), working memory (0–19 points), language (0–1 point) and orientation (0–5 points). Additionally, the time needed to complete the individual tasks is registered and presented as total test time and subdomain test time. The GSCT is automatically scored using a computer algorithm and results are presented as the total score as well as subdomain scores. A detailed description of the GSCT test items and scoring is provided in supplement 1.

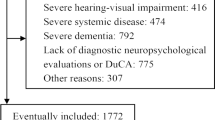

Patients

The included study population consisted of 106 patients referred to the memory clinic at Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, predominantly by primary care practitioners due to memory complaints and suspicion of cognitive decline. All patients referred to the clinic between January 2019 and January 2020 were asked to participate in the study. No exclusion criteria were established a priori. If a patient fulfilled the criteria for inclusion (i.e. referred for investigation of suspect dementia at the memory clinic and provided informed consent) they were included in the study. A total of 106 patients accepted participation in the study. Five patients did not complete GSCT (two with MCI, two with subjective cognitive impatient [SCI] and one with dementia) and three patients displayed test scores with evident irregularities (one with MCI, one with SCI and one with dementia) and were excluded from the final analysis, thus leaving 98 complete cases. Irregularities included two patients whom started the test multiple times and one patient with a congenital cognitive deficiency resulting in test scores below 2 SD from the mean on both MoCA and GSCT.

All patients included in the study underwent the standard investigative procedure for dementia assessment as conducted at Karolinska University Hospital Memory Clinic. The investigative process is completed in its entirety in one week and includes; brain imaging, lumbar punctures for analysis of CSF biomarkers and neuropsychological assessment including administration of different cognitive rating scales, including MoCA. Patients received a dementia or MCI diagnosis according to the ICD-10 classification and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) criteria were used as clinical support (29). If no evidence of neurodegeneration was observed patients were provided with an SCI diagnosis based on the ICD-10 classification (30). Final diagnosis was determined by specialist in geriatric medicine. In parallel, patients who accepted inclusion in the study completed the self-administered GSCT during the investigative process. GSCT was, in all cases, administered after MoCA, but not during the same day. Patients were provided a tablet and conducted GSCT alone with a health care provider adjacent if any technical difficulties would arise. The GSCT is a self-administered and all test instructions are provided by the platform. The test is intended to be performed in a home environment without any assistance. Information regarding patients GSCT scores, MoCA scores, age, gender and final diagnosis were collected for statistical analysis. All included patients provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Registration number: 2018/998-31/1.

The mean age for the whole included population (n=98) was 58 years. 5 patients were below 50 years of age (5%), 58 patients were between 50 and 60 years of age (59%), 34 patients were between 61 and 70 years of age (35%) and one patient over 70 years (1%) Altogether, 67% (n=65) of the patients were assessed without any signs of neurodegenerative disorder and diagnosed with SCI. 24% were diagnosed with MCI, and 9% received a dementia diagnosis. The dementia group consisted of 8 patients with AD and 1 patient with vascular dementia.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were done using Statistica software (version 13). Baseline descriptive characteristics were calculated and are provided in Table 1. The rating scales (GSCT and MoCA) were treated as both continuous and dichotomous variables when identifying optimal cut-off levels based on sensitivity and specificity analysis. Both parametric and non-parametric tests were used for the analysis to validate findings and are reported if discrepancies were seen. Agreement between test measures were analyzed using standardized concordance correlation coefficient and analysis of Bland-Altman plot. Association between GSCT and MoCA was assessed using Pearson correlation. The internal consistency of GSCT was analyzed using Cronbach’s alpha index.

ANOVA was used to assess the differences in cognitive test scores categorized by diagnostic subgroups. Post-hoc analysis was conducted using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) method. Logistic regression of total test scores was done in order to compare odds ratio between the tests.

Validation of GSCT total score against MoCA required the following to be established or calculated: ROC curves, the area under the curve (AUC) values with 95 % confidence intervals and sensitivity/specificity levels. Analyses were performed to estimate optimal cutoff values based on the best-compiled outcome from a range of sensitivity and specificity levels when testing the continuous scale against a dichotomous test of reference (SCI vs dementia and SCI vs MCI). Adjustment for multiple comparisons was done using the FDR-method. The presented p-values are adjusted values with the FDR-method. An adjusted p-level of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline data, psychometric properties and normative data

Baseline patient characteristics, including cognitive test scores, are provided in Table 1. The mean score for GSCT was 45 points in the SCI group, 36 points in the MCI group and 28 points in patients with dementia.

The correlation between GSCT and MoCA was (r(96) = 0.82, p <0.01). Standardized concordance correlation coefficient between GSCT and MoCA was 0.82, indicating a high level of agreement. Agreement between the GSCT and MoCA was also analyzed using a Bland-Altman plot with standardized values showing that 97 % of data points lie within ±2SD of the mean difference, see figure 1. Estimation of the internal consistency of GSCT showed a standardized Cronbach’s alpha index of α = 0.87.

Age was not significantly correlated with GSCT scores (r =−0.16, p=0.1). Diagnostic subgroup was significantly associated with age (F(2, 95) = 4,8 = 0.02), with post hoc test showing a significant difference between dementia and SCI patients (mean 63 vs 57 years, p=0.01) but not between SCI and MCI (mean 57 vs 60 years, p=0.08) or MCI and dementia patients (mean 60 vs 63 years, p=0.2). No differences in GSCT scores were observed depending on gender (t (96) =−0.3, p= 0.74) with males having a mean score of 41 points and females 40.4. Finally, both age, gender and education were included in an ANCOVA showing that education (F(1, 93) = 5.4, p= 0.03) was significantly associated with GSCT scores in contrast to age (F(1, 93) = 2.9, p = 0.1) and gender (F(1, 93) = 0.74, p = 0.4). Patients with more than 12 years of education showed higher mean test scores as compared to patients with 12 years or less (mean 42.2 vs 37.6 points, p = 0.05). GSCT total test time differed significantly depending on diagnostic subgroup (F(2, 95) = 36.4, p < 0.01) (Figure 2). Post-hoc tests showed that the differences in mean scores were significant between all three subgroups with SCI patients showing a mean test time of 1057 seconds compared to 1296 and 2065 seconds for MCI and dementia patients respectively (SCI vs MCI, p < 0.01) (SCI vs dementia, p < 0.01) (MCI vs dementia, p < 0.01).

Between-group differences in GSCT and MoCA

Average GSCT scores differed significantly depending on diagnostic subgroup (F(2, 95) = 20.3, p < 0.01). Post-hoc tests showed that the differences in mean scores were significant between all three subgroups (SCI vs MCI, p < 0.01) (SCI vs dementia, p < 0.01) (MCI vs dementia, p = 0.02).

Mean MoCA scores were also significantly different depending on diagnosis (F(2, 95) = 29.5, p < 0.01) and the mean scores were significantly different for all three subgroups (SCI vs MCI, p < 0.01) (SCI vs dementia, p < 0.01) (MCI vs dementia, p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Box plots for test scores for both GSCT and MoCA categorized by diagnosis can be seen in Figure 3. Odds ratios were calculated showing a one unit increase on the GSCT increased the odds of being healthy by 1.15 (CI 95% 1.07–1.22) while MoCA was associated with a 1.47 increase in odds (CI 95% 1.22–1.76).

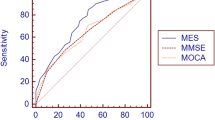

Accuracy and comparison with MoCA

GSCT showed very good to excellent discriminative properties at a wide range of cut-off values. When including all patients, thus coding both MCI and dementia patients into a binary classification of healthy/cognitively impaired, GSCT total score displayed an AUC value of 0.80 with 95% CI [0.70–0.90], whereas MoCA showed an AUC value of 0.80 with CI [0.70–0.90]. MoCA showed a sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.54 at a cut-off of <=26 while GSCT total score displayed 0.91 and 0.55 in sensitivity and specificity respectively at a cut-off of <=45. Figure 4 shows respective AUC curves and Table 2 presents the respective summary statistics.

When assessing the accuracy in discriminating between SCI and MCI patients GSCT showed an AUC value of 0.74 with 95% CI [0.62–0.85] whereas MoCA showed an AUC value of 0.74 with 95% CI [0.61–0.85]. Sensitivity and specificity at a cut-off level of <=45 was 0.88 and 0.55, respectively for GSCT total score. Whereas MoCA, at the traditional cut-off of <=26, displayed a sensitivity of 0.83 and specificity of 0.54 (Table 2). Both tests were excellent at discriminating dementia patients from SCI. GSCT showed an AUC score of 0.96 with 95% CI [0.92–0.1] while MoCA had an AUC score of 0.98 with 95% CI [0.95–0.1]. At the traditional MoCA cut-off of <= 26, sensitivity and specificity scores were 1 and 0.54, respectively whereas GSCT using a cut-off of <=35.5 showed a sensitivity of 1 and specificity of 0.9. As seen in Figure 5, both tests show good capabilities in discriminating between different diagnostic subgroups in this material, although some overlap between MCI and SCI patients existed for both tests. GSCT was marginally better at discriminating MCI from SCI patients as compared to MoCA. No patients with dementia scored within the normal range for either test.

Discussion

In this study, we present the first results on a newly developed digital cognitive test provided by Geras Solutions. GSCT displayed good agreement with MoCA based on concordance correlation analysis and Bland-Altman plot indicating that both tests measure similar cognitive domains. Additionally, normative data regarding the influence of age, gender and education was analyzed showing that education, but not age and gender, affected test scores. Individuals with more than 12 years of education had higher mean GSCT scores as compared to individuals with 12 years or less of education providing valuable information regarding scoring analysis in different demographic groups. GSCT showed equally good discriminative properties compared to the MoCA test. Both tests were excellent at discriminating dementia patients from SCI patients with a sensitivity of 1 for both GSCT and MoCA while showing a specificity of 0.9 and 0.56, respectively. This result is similar to the differential capabilities of other digital cognitive test showing sensitivity and specificity scores ranging from 0.85–1 and 0.81–1 respectively (31–33). Both tests also showed similar capabilities when discriminating between SCI and MCI patients with AUC scores of 0.74. GSCT was in this study slightly better in correctly identifying cognitive deterioration in MCI patients with a sensitivity of 0.88 compared to 0.83 for MoCA while both tests showed similar specificity of 0.55 and 0.54 receptively. The GSCT showed somewhat better sensitivity in detecting MCI patients compared to other digital screening tools, such as CogState, which previously reported sensitivity scores ranging between 0.63 and 0.84, albeit those test demonstrated higher specificity (31, 33, 34). Since GSCT is intended as a screening tool used early in the diagnostic process we believe that focus on high sensitivity is of more importance and must come at the cost of lower specificity.

Both tests demonstrated significant differences in mean test scores between all diagnostic subgroups. Additionally, the total GSCT time was also significantly different between all subgroups providing further valuable clinical information as compared to current paper and pen based cognitive screening instruments. GSCT showed very good internal consistency (α = 0.87). Based on this study, we suggest a cut-off level of <=45 for detection of MCI while values <=35.5 indicate manifest dementia.

Overall, GSCT performed at least as well as compared to currently available screening tools for dementia disorders (MoCA) while simultaneously providing several advantages. First, the test is administered via a digital device, thus eliminating the time-consuming need for testing provided by health care practitioners while also increasing the availability of cognitive screening. Given the earlier reported estimated increase in dementia prevalence combined with possible disease-modifying drugs, there is an urgent need for increased accessibility. Additionally, the digital set up of the test eliminates administration bias from health care providers and creates a more homogenous diagnostic tool. Albeit, future studies are needed to test the device in a setting without health care providers nearby. Furthermore, the possibility to register total and domain-specific test time may provide valuable clinical information potentially increasing the diagnostic capabilities, a hypothesis needing further testing in future research. Due to current trends, the development of an effective and accurate digital screening tool for cognitive impairment is of utter importance. Given a sufficiently accurate test, patients scoring in the normal range would not need to undergo further examination in the hospital setting. Instead, this digital screening instrument could identify the proper individuals in need of expanded testing e.g. MRI, CSF analysis and detailed neuropsychological testing, thus saving resources for the health care system and allocating interventions for those in need.

Limitations

In this initial study we were not able to include healthy subjects. Instead, SCI patients were used as “healthy controls”. Although these patients have a self-reported presence of cognitive dysfunction, no objective findings for the presence of an ongoing neurodegenerative process could be identified. Future studies should include healthy patients without any subjective symptoms. Additionally, future larger normative studies are required to investigate how factors such as age, gender and education affect GSCT performance in order to increase validity and diagnostic accuracy. Another limitation of the test is the lack of information regarding test-retest reliability. In this preliminary trial, we were unable to obtain longitudinal data thus hindering such analysis. Future studies must include longitudinal measurements in order to determine the test-retest reliability of GSCT.

Another limitation of this study is the small sample size, especially in the MCI and dementia subgroups. These findings should be interpreted with caution and future studies, including more patients with MCI and dementia disorders, are necessary to improve the accuracy of the test. Albeit the low sample size increases the risk of type 2 errors, we found significant differences for all groups in mean GSCT scores, further supporting the robustness of the findings. Continuous collection of data from new individuals will improve test performance and provide normative information. Another limitation is the fact that patients were administered GSCT during the same week as MoCA, which could potentially generate practice effects. Furthermore, all testing in the study was conducted in Swedish and all included patients were living in close proximity to Stockholm, Sweden. Thus, there may be a potential bias in the selection of the study population and future studies should investigate whether GSCT scores are affected by regional differences as well as examine the suitability of different language versions in order to improve accessibility.

Conclusions

Overall, the Geras Solutions Cognitive Test performed very well with diagnostic capabilities equal to MoCA when tested on this study population.

This report suggests that GSCT could be a viable cognitive screening instrument for both MCI and dementia. Continued testing and the collection of normative data and test-retest reliability analysis is needed to improve the validity and diagnostic accuracy of the test. Additionally, future studies should explore the diagnostic value of total test time as well as item specific test time.

References

Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M et al (2015) World alzheimer report. The global impact of dementia. An analysis of prevalance, incidence, cost and trends. Alzheimer’s Disease International, London.

Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina AM, Winblad B, et al. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017;13(1):1–7.

Xu J, Zhang Y, Qiu C, Cheng F. Global and regional economic costs of dementia: a systematic review. Lancet. 2017;390:S47.

Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: current status and prospects for the future. J Intern Med. 2018;284(6):643–63.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. 2018 National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) Research Framework NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14(1):535–62.

Lopez OL. Mild cognitive impairment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2013;19(2 Dementia):411–24.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011;7(3):280–92.

Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Vol. 12, Alzheimer’s and Dementia. Elsevier Inc.; 2016. p. 292–323.

Sheehan B. Assessment scales in dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(6):349–58.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ. A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):379–88.

Milani SA, Marsiske M, Cottler LB, Chen X, Striley CW. Optimal cutoffs for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment vary by race and ethnicity. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2018;10:773–81.

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, Trevelyan CM, Hampton T, Rayment D, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(1):CD011145.

O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, et al. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(7):963–7.

Davis DH, Creavin ST, Yip JL, Noel-Storr AH, Brayne C, Cullum S. Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015

Mitchell AJ. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(4):411–31.

Hlavka JP, Mattke S, Liu JL. Assessing the Preparedness of the Health Care System Infrastructure in Six European Countries for an Alzheimer’s Treatment. Rand Heal Q. 2019;8(3):2.

Meskó B, Drobni Z, Bényei É, Gergely B, Győrffy Z. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. mHealth. 2017;3:38–38.

Robillard JM, Lai JA, Wu JM, Feng TL, Hayden S. Patient perspectives of the experience of a computerized cognitive assessment in a clinical setting. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2018

Kim H, Hsiao CP, Do EYL. Home-based computerized cognitive assessment tool for dementia screening. J Ambient Intell Smart Environ. 2012

Wild K, Howieson D, Webbe F, Seelye A, Kaye J. Status of computerized cognitive testing in aging: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2008.

Morrison RL, Pei H, Novak G, Kaufer DI, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Ruhmel S, et al. A computerized, self-administered test of verbal episodic memory in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment and healthy participants: A randomized, crossover, validation study. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2018

Berg JL, Durant J, Léger GC, Cummings JL, Nasreddine Z, Miller JB. Comparing the Electronic and Standard Versions of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in an Outpatient Memory Disorders Clinic: A Validation Study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018

De Roeck EE, De Deyn PP, Dierckx E, Engelborghs S. Brief cognitive screening instruments for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy. 2019.

Maruff P, Lim YY, Darby D, Ellis KA, Pietrzak RH, Snyder PJ, et al. Clinical utility of the cogstate brief battery in identifying cognitive impairment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Psychol. 2013

Inoue M, Jinbo D, Nakamura Y, Taniguchi M, Urakami K. Development and evaluation of a computerized test battery for Alzheimer’s disease screening in community-based settings. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009

Memória CM, Yassuda MS, Nakano EY, Forlenza O V. Contributions of the Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment (CANS-MCI) for the diagnosis of MCI in Brazil. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2014

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 [Internet]. Fifth edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, [2013] ©2013

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization.

Scharre DW, Chang SI, Nagaraja HN, Vrettos NE, Bornstein RA. Digitally translated Self-Administered Gerocognitive Examination (eSAGE): Relationship with its validated paper version, neuropsychological evaluations, and clinical assessments. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2017;9(1).

Onoda K, Yamaguchi S. Revision of the cognitive assessment for dementia, iPad version (CADi2). PLoS One. 2014;9(10).

Possin KL, Moskowitz T, Erlhoff SJ, Rogers KM, Johnson ET, Steele NZR, et al. The Brain Health Assessment for Detecting and Diagnosing Neurocognitive Disorders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):150–6.

de Jager CA, Schrijnemaekers ACMC, Honey TEM, Budge MM. Detection of MCI in the clinic: Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of a computerised test battery, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and the MMSE. Age Ageing. 2009;38(4):455–60.

Funding

Funding: Theme Aging Research Unit had research collaboration with Geras Solutions during the study and a grant from Geras Solutions was provided to support conducting the study. The study was conducted independently at the memory clinic, Karolinska University Hospital, and the funding organizations had not been involved in analyses and writing. Other research support: Joint Program of Neurodegenerative Disorders, IMI, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED) Stiftelsen Stockholms sjukhem, Konung Gustaf V:s och Drottning Victorias Frimurarstiftelse, Alzheimer’s Research and Prevention Foundation, Alzheimerfonden, Region Stockholm (ALF and NSV grants). Advisory board (MK): Geras Solutions, Combinostics, Roche. GH: Advisory board: Gears Solutions. VB: Consultant for Geras Solutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest: MK: Advisory board: Combinostics, Roche; GH: Advisory board: Gears Solutions; VB: Consultant for Geras Solutions.

Ethical Standards: The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Registration number: 2018/998-31/1.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bloniecki, V., Hagman, G., Ryden, M. et al. Digital Screening for Cognitive Impairment — A Proof of Concept Study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 8, 127–134 (2021). https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2021.2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2021.2