Abstract

Background

Sarcopenia and frailty are often used interchangeably in clinical practice yet represent two distinct conditions and require different therapeutic approaches. The literature regarding the co-occurrence of both conditions in older patients is scarce as most studies have investigated the prevalence of sarcopenia and frailty separately.

Objectives

We aim to evaluate the prevalence and co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty in a large sample of acutely admitted older medical patients.

Design

Secondary analyses using cross-sectional data from the Copenhagen PROTECT study.

Setting

Patients were included from the acute medical ward at Copenhagen University Hospital, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, Denmark, between November 2019 and November 2021.

Participants

Acutely admitted older medical patients (≥65 years).

Measurements

Handgrip strength (HGS) was investigated using a handheld dynamometer. Lean mass (SMI) was investigated using direct-segmental multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analyses (DSM-BIA). Low HGS, low SMI, and sarcopenia were defined according to the recent definitions from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2). The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) was used to evaluate frailty, with a value > 5 indicating the presence of frailty. Patients were enrolled and tested within 24 hours of admission.

Results

This study included 638 patients (mean age: 78.2±7.6, 55% female) with complete records of SMI, HGS, and the CFS. The prevalence of low HGS, low SMI, sarcopenia, and frailty were 39.0%, 33.1%, 19.7%, and 39.0%, respectively. Sarcopenia and frailty co-occurred in 12.1% of the patients.

Conclusions

It is well-known that sarcopenia and frailty represent clinical manifestations of ageing and overlap in terms of the impairment in physical function observed in both conditions. Our results demonstrate that sarcopenia and frailty do not necessarily co-occur within the older acutely admitted patient, highlighting the need for separate assessments of frailty and sarcopenia to ensure the accurate characterization of the health status of older patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Sarcopenia and frailty are common conditions in the older population (1, 2). Sarcopenia is the condition of age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, playing a major role in the functional impairment that may occur with old age (3–10). Frailty, on the other hand, is a multidimensional clinical condition characterized by a decrease in biological reserve capacity leading to increased vulnerability and reduced ability to resist stressors such as illness, falls, or any circumstances that affect mental and physical well-being (11–14). Both frailty and sarcopenia are associated with adverse outcomes such as functional impairments, recurrent falls, hospitalization, and mortality (11, 12, 15–17). Furthermore, both conditions share etiological factors such as malnutrition, inflammation, hormonal changes, and reduced physical activity (18). The physical function impairment has been described as a possible core element shared by the two conditions (19), which can co-occur within the same individual (20).

Following the initial research in frailty and sarcopenia approximately 20 years ago, these conditions have been investigated in parallel (21). Although sarcopenia and frailty are often used interchangeably in clinical practice, they represent two distinct conditions and require different therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the prevalence and co-occurrence of the two conditions depend on the used definitions (20, 22, 23). The co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty have previously been investigated in community-dwelling older adults (22–26). However, the literature regarding the co-occurrence in older in-hospital patients is scarce as most studies have investigated the prevalence of sarcopenia and frailty separately (27).

A previous study regarding the prevalence and overlap of sarcopenia and frailty in a small cohort of older patients demonstrated that sarcopenia and frailty co-occurred in more than half of the patients (10, 20). However, the criteria for defining sarcopenia were different from the currently accepted definition from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) (10), and the study assessed frailty using the definition by Fried et al (28). Notably, more comprehensive measures such as gait speed included in the definition by Fried may not be suitable for all acutely admitted medical patients who may be immobile or affected by their acute illness (29). Indeed, a recent study evaluating the utility of several frailty screening tools concluded that the Fried definition showed the lowest feasibility in the clinical setting, and that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) among others is a suitable choice for evaluating frailty in the clinical setting (30).

As such, we aim to evaluate the prevalence and co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty in a large sample of acutely admitted older medical patients using the recent guidelines from EWGSOP2 (10) and the CFS by Rockwood (31). Additionally, we aim to characterize the groups of patients classified as ‘Neither frail nor sarcopenic’, ‘Frail only’, ‘Sarcopenic only’, and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’, and to investigate the predictive ability of the presence of these conditions with 90-day all-cause mortality post admission.

Methods and materials

Study design and participants

The current study used baseline data from the Copenhagen PROTECT study, a prospective cohort study including acutely admitted older (≥65 years) medical patients at Copenhagen University Hospital, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg (BFH), between November 2019 and November 2021. The healthcare system in Denmark is fully tax-funded where in-hospital diagnostics and treatments are carried out without direct costs to the patient (32) BFH is an acute intake community hospital in the capital of Denmark, Copenhagen with a catchment area of about 483.000 inhabitants (33). The acute medical ward covers the following medical specialties: lung- and infectious medicine, endocrinology, geriatric medicine, gastroenterology, and acute medicine (34). Patients were recruited from the acute medical ward and data were collected within 24 hours of admission. A detailed description of the study protocol can be viewed elsewhere (35).

This study included a subset of patients with a full data set on both sarcopenia measures and frailty (n=638). Patient characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), number of prior hospitalizations within the last year until index admission, residential dependency (own home/nursing home) prior to admission, and discharge destination (own home / nursing home / rehabilitation stay). Comorbidity was evaluated by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (36), and polypharmacy was present when the number of prescribed medications >5 (35). Risk of malnutrition was evaluated in a subsample (n=412) using the Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ) (37). Fall incidents within the last year until index admission were reported by the patient and classified as either no falls, 1–3 falls, or 4 or more falls.

Lean mass, muscle strength, sarcopenia & frailty

As proposed by the EWGSOP2, patients were screened for potential sarcopenia using the Strength, Assistance with walking, Rising from a chair, Climbing stairs, and Falls questionnaire (SARC-F) (38). Potential sarcopenia was present at SARC-F scores ≥ 4. Regardless of the SARC-F score, the following measurements were performed. Appendicular lean mass (ALM) was assessed using direct-segmental multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analyses (DSM-BIA) (Inbody S10, BioSpace, Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) and relative ALM (kg/height2) was reported as the skeletal muscle index (SMI). Low lean mass was defined as an SMI less than 5.5 kg/m2 and 7.0 kg/m2 for women and men, respectively, using the cut-offs from the EWGSOP2 (10). Handgrip strength (HGS) was assessed using a digital hand-held dynamometer (Model SH1001; SAEHAN Corporation, Yangdeok-Dong, Masan, South Korea) as the highest value of three attempts with the dominant hand (35). Low HGS was defined as a HGS less than 27 kg and 16 kg for men and women, respectively, using the cut-offs from the EWGSOP2 (10). Sarcopenia was reported as a dichotomous variable as the presence of low handgrip strength with concurrent low SMI. Frailty was assessed using the 9-point CFS, according to the definition by Rockwood et al (31). A frailty score ≥ 5 indicated the presence of frailty.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of interest was 90-day all-cause mortality following admission. Information regarding mortality was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System (39).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were performed to determine prevalence rates of low SMI, low HGS, sarcopenia, and frailty and reported as the relative frequency (%). Patients were stratified into four groups according to the presences of frailty and sarcopenia i.e., ‘Neither frail nor sarcopenic’, ‘Frail only’, ‘Sarcopenic only’, and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’. The group of patients with neither frailty nor sarcopenia was used as reference when comparing differences between the groups. Patient characteristics were reported as mean ± SD or relative frequency (%). Differences in patient characteristics were assessed using independent t-tests, or Chi2 with subsequent post-hoc Bonferroni corrected z-tests. Cox regression analysis was used to model survival in the four frail/sarcopenic groups and was reported as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Person-days of follow-up were calculated from date of hospital admission to date of death or end at follow-up (90 days). The model was reported both as unadjusted models, a model adjusted for age and sex and model adjusted for age, sex, and the CCI. Proportional hazard assumptions were statistically tested and found satisfactory.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29.0). The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

A total of 638 patients with complete records of both HGS, SMI, and the CFS were included in the study (mean age 78.2±7.6, 55% female). The prevalences are presented in table 1.

Patient characteristics of the total sample and according to the presence of frailty and sarcopenia are presented in table 2. Compared to the group of patients that were neither frail nor sarcopenic, patients with frailty and/or sarcopenia were significantly older, had a significantly lower HGS, a significantly higher proportion of patients at risk of severe malnutrition, and a significantly larger proportion of patients with potential sarcopenia evaluated by SARC-F. Groups including sarcopenic patients, i.e., the ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ group and ‘Sarcopenic only’, had a significantly lower BMI and a lower SMI compared to the reference group. The prevalence of severe comorbidity and polypharmacy were significantly higher in groups with frail patients i.e. the ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ and the ‘Frail only’ compared to the reference group. Furthermore, groups with frail patients also demonstrated a higher prevalence of four or more self-reported falls within the last year and a higher prevalence of two or more hospitalizations during the year up until the index admission. All patients discharged to nursing homes were classified as frail. Likewise, groups with frail patients had significantly less patients who were discharged to their own home.

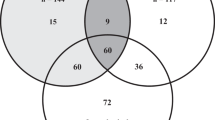

The co-occurrence of low HGS, low SMI, and frailty is illustrated in a proportional Venn diagram (40) (Figure 1). Of the 249 patients with frailty, 56% had concurrent low HGS, 44% had concurrent low SMI, and 31% had concurrent sarcopenia. Frailty co-occurred in 61% of the 126 patients with sarcopenia. Of the 638 patients, 35.6% had neither low HGS, low SMI, nor frailty. The co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty was evident in 12.1% of the total population.

The dashed line frames the group of patients with sarcopenia.

Risk of mortality 90 days post admission

The incident proportion of 90-day post admission mortality was 6.8%, 13.4%, 12.2%, and 15.6% for the ‘Neither frail nor sarcopenic’, ‘Frail only’, ‘Sarcopenic only’, and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ groups, respectively. Compared to the reference group, the ‘Frail only’ and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ groups demonstrated a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality 90-day post admission (both p<0.05) (Table 3). In a second model adjusted for the effect of age and sex, the higher risk of mortality remained statistically significant in the ‘Frail only’ (p<0.05), while the higher risk of mortality in the ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ group was not statistically significant (p=0.06). Compared to the reference group, the ‘Frail only’, ‘Sarcopenic only’, and the ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ groups did not demonstrate an increased risk of all-cause mortality 90-day post admission in a third model adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity (Table 3).

Discussion

The pathophysiological similarities between sarcopenia and frailty, and the physical function impairment, which has been described as a possible core element shared by the two conditions, has led to a continuous debate regarding the causal relationship between the two (19). Perhaps the point is not determining whether one is due to the other, but rather defining the aspects and characteristics shared by patients with or without the conditions. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the prevalence and co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty in a large sample of acutely admitted older medical patients using the recent guidelines from EWGSOP2 (10) and The Clinical Frailty Scale by Rockwood (31). Frailty was a common condition present in more than 1/3 of older patients. Sarcopenia had a prevalence of approximately 20%, whereas the elements of sarcopenia, low HGS and low SMI, were present in 39% and 30% of older patients, respectively. This is in line with another study on geriatric outpatients demonstrating that the prevalence of frailty was higher than the prevalence of sarcopenia (22).

Co-occurrence of frailty and sarcopenia

Previous research has demonstrated a need for separate assessments of both frailty and sarcopenia to ensure the accurate characterization of the health status of older people (23, 41). While the majority of these studies have been performed on community-dwelling older people, the literature regarding the co-occurrence of both conditions in hospitalized older patients is scarce as most studies have investigated the prevalence of sarcopenia and frailty separately (27). Notably, the characterization of patients presenting with frailty and/or sarcopenia may aid in risk assessment in clinical practice.

Although frailty and sarcopenia are common conditions, they do not necessarily co-occur within the older acutely admitted patient (Figure 1). In fact, our data, and the study by Reijnierse et al, show that sarcopenic patients are more likely to be frail than frail patients to be sarcopenic (22). In contrast, other studies have found frail older people more likely to be sarcopenic than sarcopenic older people to be frail (24, 42, 43), which may be caused by differences in definitions, assessments, cut-off values, and study populations. Indeed, some studies have demonstrated a higher co-occurrence of sarcopenia and frailty assessed using the Fried definition (22, 28). This is expected as the Fried definition views frailty as physical frailty as opposed to Rockwood who defines frailty as a “cumulation of deficits” indicating that patients are at greater risk when they have several health deficits (12, 31). From this perspective, frailty can be viewed as an accumulation of risk factors for adverse events ultimately leading to greater risk of hospitalizations, increased use of health care services, and mortality (44). We have previously demonstrated a low concordance between frailty assessed by the Fried definition and the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), and a better prognostic ability of the CFS in terms of predicting 90-day mortality in older acutely admitted patients (45, 46). In this regard, the Clinical Frailty Scale is receiving increased attention as a screening tool in clinical practice and is often used in the hospital setting due to the feasibility and ease-of-use (30, 47). Notably, the low concordance between frailty screening tools, as well as differences in prevalence rates and predictive abilities could indicate the presence of several subtypes of frailty (30).

Our data demonstrate that patients with neither frailty nor sarcopenia had a significantly higher mean handgrip strength and a significantly lower prevalence of severe malnutrition compared to patients with a condition, regardless of whether they were frail only, sarcopenic only, or both frail and sarcopenic. This supports the notion that physical function impairment is a shared feature of both conditions (19) yet emphasize the need for the separate assessment of frailty and sarcopenia as they are both associated with adverse outcomes. To our surprise, the prevalence of potential sarcopenia, evaluated by SARC-F, was higher in groups including frail patients (i.e., the group of frail only and the group with both frail and sarcopenic patients) compared with sarcopenic only patients. Whether the SARC-F screening has better discriminative performance for frailty than sarcopenia should be investigated in a future study.

The prevalence of severe comorbidity and polypharmacy were significantly higher in groups with frail patients i.e. the group of frail only patients and the group of both frail and sarcopenic patients compared to the reference group. This was also reflected as a higher proportion of frail patients with two or more hospitalizations during the year up until the index admission compared to the reference group. These results highlight the increased health deficits of frail patients and underlines the need for the systemic assessment of frailty for the identification of patients at risk.

Mortality risk

The incident proportion of all-cause mortality was approximately twice as high in groups of patients displaying either frailty, sarcopenia, or a combination of the two. Notably, as demonstrated by the results from the Cox regression analyses, only groups entailing patients with frailty (i.e. the ‘Frail only’ and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ groups) exhibited a higher risk of all-cause 90-day post admission mortality compared to patients with neither frailty nor sarcopenia. Being classified as frail appeared to entail a two-fold increased risk of dying following an acute admission, with hazard ratios of 2.4 and 2.0 for the ‘Frail only’ and ‘Both frail and sarcopenic’ groups, respectively (both p<0.05). However, in analyses adjusted for the effect of age and sex, only the ‘Frail only’ group remained statistically significant (HR 1.91, p<0.05), potentially reflecting a type II error caused by insufficient power in the ‘Both frail and sarcopenic group’ (HR 2.00, p=0.06).

In a third model adjusted for the effect of age, sex, and comorbidity, neither group displayed a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality following 90-day of admission. Thus, when comorbidity is taken into account, it appears that frailty and sarcopenia does not add additional prognostic value in terms of predicting 90-day post admission all-cause mortality risk in the acute setting. Conversely, the study by Thompson et al found that community-dwelling older individuals with both frailty and sarcopenia demonstrated a significantly higher risk of 10-year mortality compared to older individuals with neither frailty nor sarcopenia in multivariable analyses adjusted for the effect of age, sex, and multimorbidity among others (26). The discrepancy in results may reflect differences in follow-up time, population characteristics, or an effect of acute admission. Indeed, the need for acute health care service significantly increases the risk of 1-year mortality (48).

Limitations

This study has some limitations that needs to be addressed. One must take into account that this study is based on patients with complete records of both frailty, handgrip strength, and body composition. As the main reason for missing measurements entailed an inability to mobilize patients from their hospital bed to obtain the body weight needed for the body composition algorithm (49), it is possible that the prevalence of frailty and sarcopenia, and thus the co-occurrence of the conditions, is even higher than reported here. Of note, the prevalence of frailty in the total cohort was 48%, with low HGS co-occurring in 63% of these patients (data not shown). Here we report that frailty was present in 39% of the patients, with low HGS co-occurring in 56% of these patients. Although the prevalence of frailty and sarcopenia are potentially higher in the total cohort, the co-occurrence of both conditions appear fairly similar.

Conclusion

It is well-known that sarcopenia and frailty represent clinical manifestations of ageing and overlap in terms of the impairment in physical function observed in both conditions. Notably, when comorbidity is taken into account, frailty and sarcopenia does not add additional prognostic value in terms of predicting 90-day post admission all-cause mortality risk in the acute setting. Our results demonstrate that sarcopenia and frailty do not necessarily co-occur within the older acutely admitted patient. Indeed, 12.1% and 7.7% of patients displayed non-sarcopenic frailty or non-frail sarcopenia, respectively, highlighting the necessity of separate assessments of frailty and sarcopenia to ensure the accurate characterization of the health status of older patients.

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Topinkova E, Michel JP. Understanding sarcopenia as a geriatric syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010 Jan;13(1):1–7. Epub 2009/11/17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333c1c1. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 19915458.

Ruiz M, Cefalu C, Reske T. Frailty syndrome in geriatric medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2012 Nov;344(5):395–8. Epub 2012/06/29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318256c6aa. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 22739566.

Vandervoort AA. Aging of the human neuromuscular system. Muscle Nerve. 2002 Jan;25(1):17–25. Epub 2001/12/26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.1215. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 11754180.

Singh MA. Exercise comes of age: rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2002 May;57(5):M262–82. Epub 2002/05/02. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/57.5.m262. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 11983720.

Roubenoff R. Sarcopenia: a major modifiable cause of frailty in the elderly. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2000;4(3):140–2. Epub 2000/08/11. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 10936900.

Roth SM, Ferrell RF, Hurley BF. Strength training for the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2000;4(3):143–55. Epub 2000/08/11. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 10936901.

Narici MV, Reeves ND, Morse CI, Maganaris CN. Muscular adaptations to resistance exercise in the elderly. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2004 Jun;4(2):161–4. Epub 2004/12/24. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 15615118.

Mazzeo RS CP, Evans WJ, Fiatarone M, Hagberg J, McAuley E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):992–1008.

Rantanen T, Harris T, Leveille SG, Visser M, Foley D, Masaki K, Guralnik JM. Muscle strength and body mass index as long-term predictors of mortality in initially healthy men. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2000 Mar;55(3):M168–73. Epub 2000/05/05. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/55.3.m168. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 10795731.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M, Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older P, the Extended Group for E. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 Jul 1;48(4):601. Epub 2019/05/14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz046. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 31081853.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England). 2013 Mar 02;381(9868):752–62. eng. Epub 2013/02/12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 23395245.

Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;9:433–41. eng. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s45300. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 24672230.

Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Katz PR, Malmstrom TK, McCarter RJ, Gutierrez Robledo LM, Rockwood K, von Haehling S, Vandewoude MF, Walston J. Frailty consensus: a call to action. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013 Jun;14(6):392–7. eng. Epub 2013/06/15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 23764209.

Howlett SE, Rockwood K. New horizons in frailty: ageing and the deficit-scaling problem. Age Ageing. 2013 Jul;42(4):416–23. Epub 2013/06/07. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft059. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 23739047.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Orav JE, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R, Schlogl M, Staehelin HB, Willett WC, Dawson-Hughes B. Comparative performance of current definitions of sarcopenia against the prospective incidence of falls among community-dwelling seniors age 65 and older. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2015 Dec;26(12):2793–802. Epub 2015/06/13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3194-y. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 26068298.

Morley JE, Abbatecola AM, Argiles JM, Baracos V, Bauer J, Bhasin S, Cederholm T, Coats AJ, Cummings SR, Evans WJ, Fearon K, Ferrucci L, Fielding RA, Guralnik JM, Harris TB, Inui A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kirwan BA, Mantovani G, Muscaritoli M, Newman AB, Rossi-Fanelli F, Rosano GM, Roubenoff R, Schambelan M, Sokol GH, Storer TW, Vellas B, von Haehling S, Yeh SS, Anker SD, Society on Sarcopenia C, Wasting Disorders Trialist W. Sarcopenia with limited mobility: an international consensus. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011 Jul;12(6):403–9. Epub 2011/06/07. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.014. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 21640657.

De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, Toye KR, Kaufman JM, Lapauw B, Goemaere S. Validation of the FNIH sarcopenia criteria and SOF frailty index as predictors of long-term mortality in ambulatory older men. Age Ageing. 2016 Sep;45(5):602–8. Epub 2016/04/30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw071. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 27126327.

Jeejeebhoy KN. Malnutrition, fatigue, frailty, vulnerability, sarcopenia and cachexia: overlap of clinical features. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012 May;15(3):213–9. Epub 2012/03/28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328352694f. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 22450775.

Cesari M, Landi F, Vellas B, Bernabei R, Marzetti E. Sarcopenia and physical frailty: two sides of the same coin. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:192. Epub 2014/08/15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00192. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 25120482.

Gingrich A, Volkert D, Kiesswetter E, Thomanek M, Bach S, Sieber CC, Zopf Y. Prevalence and overlap of sarcopenia, frailty, cachexia and malnutrition in older medical inpatients. BMC geriatrics. 2019 Apr 27;19(1):120. Epub 2019/04/29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1115-1. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 31029082.

Bauer JM, Sieber CC. Sarcopenia and frailty: a clinician’s controversial point of view. Exp Gerontol. 2008 Jul;43(7):674–678. Epub 2008/04/29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2008.03.007. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 18440743.

Reijnierse EM, Trappenburg MC, Blauw GJ, Verlaan S, de van der Schueren MA, Meskers CG, Maier AB. Common Ground? The Concordance of Sarcopenia and Frailty Definitions. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2016 Apr 1;17(4):371e7–12. Epub 2016/02/29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.013. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 26922807.

Davies B, Garcia F, Ara I, Artalejo FR, Rodriguez-Manas L, Walter S. Relationship Between Sarcopenia and Frailty in the Toledo Study of Healthy Aging: A Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018 Apr;19(4):282–286. Epub 2017/10/29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.014. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 29079029.

Mijnarends DM, Schols JM, Meijers JM, Tan FE, Verlaan S, Luiking YC, Morley JE, Halfens RJ. Instruments to assess sarcopenia and physical frailty in older people living in a community (care) setting: similarities and discrepancies. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015 Apr;16(4):301–8. Epub 2014/12/23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.011. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 25530211.

Frisoli A, Jr., Chaves PH, Ingham SJ, Fried LP. Severe osteopenia and osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and frailty status in community-dwelling older women: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) II. Bone. 2011 Apr 1;48(4):952–7. Epub 2011/01/05. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.025. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 21195216.

Thompson MQ, Yu S, Tucker GR, Adams RJ, Cesari M, Theou O, Visvanathan R. Frailty and sarcopenia in combination are more predictive of mortality than either condition alone. Maturitas. 2021 Feb;144:102–107. Epub 20201201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.11.009. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 33358201.

Ligthart-Melis GC, Luiking YC, Kakourou A, Cederholm T, Maier AB, de van der Schueren MAE. Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Malnutrition Frequently (Co-)occur in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020 Sep;21(9):1216–1228. Epub 2020/04/25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.006. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 32327302.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146–56. eng. Epub 2001/03/17. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 11253156.

Ostir GV, Berges I, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS, Ottenbacher KJ, Guralnik JM. Assessing gait speed in acutely ill older patients admitted to an acute care for elders hospital unit. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Feb 27;172(4):353–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1615. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 22371922.

Checa-Lopez M, Rodriguez-Laso A, Carnicero JA, Solano-Jaurrieta JJ, Saavedra Obermans O, Sinclair A, Landi F, Scuteri A, Alvarez-Bustos A, Sepulveda-Loyola W, Rodriguez-Manas L. Differential utility of various frailty diagnostic tools in non-geriatric hospital departments of several countries: A longitudinal study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023 Feb 28:e13979. Epub 2023/03/02. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13979. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 36855840.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2005 Aug 30;173(5):489–95. eng. Epub 2005/09/01. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 16129869.

Health Mo. Healthcare in Denmark: an overview. 2017. Available from: http://www.sum.dk/english.

Gregersen R, Fox Maule C, Husum Bak-Jensen H, Linneberg A, Nielsen OW, Thomsen SF, Meyhoff CS, Dalhoff K, Krogsgaard M, Palm H, Christensen H, Porsbjerg C, Antonsen K, Rungby J, Haugaard SB, Petersen J, Nielsen FE. Profiling Bispebjerg Acute Cohort: Database Formation, Acute Contact Characteristics of a Metropolitan Hospital, and Comparisons to Urban and Rural Hospitals in Denmark. Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:409–424. Professor Olav Wendelboe Nielsen reports speaker fees from Novartis and Roche, outside the submitted work. Dr Christian S Meyhoff reports indirect research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim to his department, research grants from Merck, Sharp & Dohme to his department, personal fees for research and lecture from Radiometer, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr Christian S Meyhoff has a patent «Wireless Assessment of Respiratory and circulatory Distress (WARD) - Clinical Support System (CSS) - an automated clinical support system to improve patient safety and outcomes» pending to WARD 247 ApS, which he is a co-founder. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work. Epub 20220331. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S338149. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 35387318.

Hovedstaden R. Hospitalsplan 2020. https://www.regionh.dk/til-fagfolk/Sundhed/hospitaler/HOPP/Documents/Hospitalsplan%202020.pdf: 2015. [cited 2023 30th of May]. Danish.

Kamper RS, Schultz M, Hansen SK, Andersen H, Ekmann A, Nygaard H, Helland F, Wejse MR, Rahbek CB, Noerst T, Pressel E, Nielsen FE, Suetta C. Biomarkers for length of hospital stay, changes in muscle mass, strength and physical function in older medical patients: protocol for the Copenhagen PROTECT study-a prospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2020 Dec 29;10(12):e042786. Epub 2020/12/31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042786. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 33376179.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. Epub 1987/01/01. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 3558716.

Kruizenga HM, Seidell JC, de Vet HC, Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA. Development and validation of a hospital screening tool for malnutrition: the short nutritional assessment questionnaire (SNAQ). Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2005 Feb;24(1):75–82. Epub 2005/02/01. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2004.07.015. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 15681104.

Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: a simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013 Aug;14(8):531–2. Epub 20130625. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.018. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 23810110.

Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014 Aug;29(8):541–9. Epub 2014/06/27.doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 24965263.

Hulsen. DeepVenn — a web application for the creation of area-proportional Venn diagrams using the deep learning framework Tensorflow.js. arXiv. 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.04597.

Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M, Tosato M, Martone AM, Bernabei R, Onder G, Marzetti E. Sarcopenia as the Biological Substrate of Physical Frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015 Aug;31(3):367–74. Epub 2015/07/22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2015.04.005. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 26195096.

Spira D, Buchmann N, Nikolov J, Demuth I, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Eckardt R, Norman K. Association of Low Lean Mass With Frailty and Physical Performance: A Comparison Between Two Operational Definitions of Sarcopenia-Data From the Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II). The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2015 Jun;70(6):779–84. Epub 2015/02/02. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu246. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 25638537.

Nishiguchi S, Yamada M, Fukutani N, Adachi D, Tashiro Y, Hotta T, Morino S, Shirooka H, Nozaki Y, Hirata H, Yamaguchi M, Arai H, Tsuboyama T, Aoyama T. Differential association of frailty with cognitive decline and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015 Feb;16(2):120–4. Epub 2014/09/24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.07.010. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 25244957.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007 Jul;62(7):722–7. Epub 2007/07/20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 17634318.

Nygaard H, Henriksen M, Suetta C, Ekmann A. Comparison of two frailty screening tools for acutely admitted elderly patients. Dan Med J. 2022 Jul 6;69(8). Epub 2022/08/13. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 35959830.

Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, Pederson J, Lau D, Padwal RS, Forhan M, Bakal JA, McAlister FA. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: Multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. Journal of hospital medicine. 2016 Aug;11(8):556–62. eng.Epub 2016/05/18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2607. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 27187268.

Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC geriatrics. 2020 Oct 7;20(1):393. Epub 2020/10/09. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01801-7. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 33028215.

Flojstrup M, Henriksen DP, Brabrand M. An acute hospital admission greatly increases one year mortality - Getting sick and ending up in hospital is bad for you: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. European journal of internal medicine. 2017 Nov;45:5–7. Epub 2017/10/11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2017.09.035. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 28988718.

Kamper RS, Nygaard H, Ekmann A, Schultz M, Hansen SK, Hansen P, Pressel E, Rasmussen J, Suetta C. Feasibility of Assessing Older Patients in the Acute Setting: Findings From the Copenhagen PROTECT Study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2023 Aug 8. Epub 20230808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.07.002. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 37567243.

Funding

Funding: The work is supported by funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation; grant number NNF18OC0052826. Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: All parts of the trial procedures are performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethical approval: The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg (ID: H-19039214).

Additional information

Trial registration: The Copenhagen PROTECT Study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov with the trial registration ID: NCT04151108.

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nygaard, H., Kamper, R.S., Ekmann, A. et al. Co-Occurrence of Sarcopenia and Frailty in Acutely Admitted Older Medical Patients: Results from the Copenhagen PROTECT Study. J Frailty Aging 13, 91–97 (2024). https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2024.23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2024.23