Abstract

Background

Most people value quality of life over mere duration. At least 50% of people are extremely averse to ever living in a nursing home (NH).

Objectives

Assess whether pre-operative frailty is associated with new, post-operative NH placement.

Design, Setting

Retrospective, population-based cohort study in the Canadian province of Manitoba, 2000–2017.

Participants

7408 persons ≥65 years undergoing any of 16 specific, elective, noncardiac surgeries of varying Operative Surgical Stress (OSS).

Measurements

The primary outcome was new admission to a NH, or being placed on a waiting list for a NH, within 180 days of index hospital admission, among index hospital survivors. Frailty was assessed from administrative data by the Preoperative Frailty Index (pFI), which ranges 0–1. Other outcomes were 30-day and 90–180 day mortality, and post-hospital medical resource use to 180 days. Analyses used multivariable regression models, adjusted for age, sex, OSS, year of surgery, anesthetic technique, and socioeconomic status. P-values were adjusted for the six outcomes.

Results

Subjects had mean age (±SD) of 74±7 yrs; 61% were male. pFI ranged 0–0.68, with a mean±SD of 0.21±0.09. All six outcomes were significantly associated with greater frailty. Each additional 0.1 unit increase in pFI was associated with a hazard ratio for new NH admission or wait-listing of 3.01 (p<0.0006).

Conclusions

While our study agrees with prior work indicating that greater frailty is associated with higher probability of post-operative discharge to a NH, it overcomes a number of limitations of all prior work. Strong arguments follow that prospective surgical candidates be evaluated for their degree of frailty, and that their informed consent include discussion of the possibility of survival with loss of independence

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most people feel that their quality of life is at least as important as is its duration (1). Those with and without chronic illnesses indicate that loss of functional independence is a key determinant of low quality of life (2–4). In a landmark study, Fried et al. found that among outpatients over age 60 years with limited life expectancies, only 26% would accept even low burden treatments if the result would be severe functional impairment (5). Nursing homes (NH) are residential long-term care facilities providing around-the-clock personal and nursing care for people who are unable to care for themselves. In modern society, NH placement is a very common consequence of loss of physical or cognitive function (6, 7). When asked, half or more of people indicate an extreme aversion to ever living in a NH (8–11).

Legal and ethical principles concur that informed consent for surgical procedures should include discussion of all procedural risks that are common, and those that are serious in the context of patients’ values and quality of life (12, 13). The above information indicates that the possibility of surgery resulting in the need for NH placement would be considered serious by most people.

For these reasons it is important to identify risk factors for postoperative NH placement among community-dwelling people. Frailty is a promising risk factor for this purpose. Frailty is a “multidimensional syndrome of loss of reserves (energy, physical ability, cognition, health) that gives rise to vulnerability” (14), and makes one less adaptable to stressors (15), such as surgery. Although it is more common with older age and a greater burden of chronic comorbid illness, one formulation identifies it as a phenotype (16) which can occur at any age and in the absence of any specific comorbidities. Frailty has been associated with a variety of adverse postoperative outcomes, including longer index hospital length of stay, complications, higher short-term and long-term mortality, and higher costs (17, 18).

A recently published meta-analysis identified 22 publications on whether frailty is related to postoperative discharge location (17), and we identified three others (19–21). However, this literature is problematic in regards to preoperative living situations considered, type of long-term care facilities, timing of admission to long-term care, and statistical methods. We undertook a population-based study that addresses all those limitations. We hypothesized that preoperative frailty is associated with the need for NH placement at or in the interval after index hospital discharge for elective, non-cardiac surgery. Furthermore, we hypothesized that frailty is associated with postoperative mortality and medical resource use.

Methods

Data for this retrospective, population-based cohort study derives from Research Data Repository of the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (22), including the approximately 767,000 residents of the Winnipeg Health Region of the Canadian Province of Manitoba (23). Manitoba has universal, single-payer health care. General cohort inclusion criteria were people during 2010–2017: (i) aged 65 years or older on the date of index hospitalization in which they received, (ii) any of 16 specific, elective, noncardiac surgeries performed in a main operating room of an acute care hospital, (iii) living in the community pre-operatively, (iv) registered with the provincial health system for two years prior to the index procedure and (v) registered for the lesser of one year after the index procedure or until death.

Elective surgeries were identified in the Canadian Discharge Abstract Database (24) as having occurred within 36 hours after elective hospital admission. For patients who experienced more than one qualifying hospitalization during the study interval, only the first was included in our analyses.

The 16 procedures represented varying degrees of Operative Surgical Stress (OSS) (25). OSS ranges from 1–5 with higher values representing higher degrees of physiologic stress, and associated with increasing rates of postoperative death. For each OSS value 2, 3, 4 and 5, our analysis included the four procedures of highest frequency in Manitoba, identified using nationally standardized procedure codes (eTable 1). If during a qualifying hospitalization a patient had multiple qualifying surgical procedures, the one with highest OSS was considered the index procedure.

The exposure of interest was frailty, for which we used the Preoperative Frailty Index (pFI), a hybrid measure derived from readily available administrative (claims) data (26). It ranges from 0–1, with higher values indicating greater frailty.

We evaluated six outcomes (Table 1). The outcome of primary interest was new admission to a NH, or being placed on the provincial waiting list for a NH, within 180 days of index hospital admission, among persons who left hospital alive. Thus persons in or awaiting NH care within 90 days prior to the index hospitalization were excluded. Unlike in some other jurisdictions, a large majority of people admitted to NHs in Manitoba die there (27), and thus this cohort essentially represents community-dwelling individuals who were newly and permanently admitted to NH in the six months after surgery.

Mortality outcomes were 30-day mortality, and 180-day mortality among those who survived to 90 days; the latter functionally removes the contribution of short-term mortality from consideration (28). Reasoning that persons in palliative care are not specifically seeking to avoid death, we excluded those preoperatively or postoperatively enrolled in provincial palliative care programs from the mortality outcomes.

Post-hospital resource use outcomes among those who were discharged alive were the numbers of: outpatient clinic visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospital-days. These were prorated to 180 days, e.g. a person who had 3 visits and died at post-hospital day#60 would have a prorated value of 9 visits over 180 days. Because pro-rating could appear to result in resource use outliers among those who died soon after discharge (e.g. one emergency room visit post-discharge but before death at 7 days would be pro-rated to 26 visits), we excluded individuals who died within 14 days post-discharge. And because NH residents receive much of their care from physicians in the nursing homes themselves, for these outcomes we also excluded persons living in NHs before the index surgery or who were admitted to a NH directly after the index hospitalization.

Analyses were via multivariable regression models (Table 1). We allowed for the possibility that frailty was nonlinearly related to the outcomes by expressing the pFI as a 4-knot restricted cubic spline. Nonlinearity was identified by a combination of statistical significance of the omnibus test for the nonlinear spline terms and graphical judgement (29). If the relationship was linear we report the linear coefficient; for nonlinear relationships we indicate the statistical significance of the omnibus test for all the spline terms, and show the relationship graphically (29).

Six covariates included in our analysis were: age; sex; OSS; year of surgery; anesthetic technique (general vs. any other); and area-level socioeconomic status assessed by the standardized SEFI-2 score, for which higher values represent lower socioeconomic status (30). Comorbid health conditions were excluded because numerous of them are included in the pFI.

For some of our outcomes, including the primary outcome, there were relatively few events compared to the number of covariates we wished to include. To avoid model overfitting by ensuring the usual goal of at least 10 events per independent variable (31), we performed variable reduction using principal components analysis (32), retaining at least the components with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0 (Appendix 1) (32).

Statistical analysis used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To avoid inflated Type I error rates in allowing equal consideration to the associations between frailty and the six outcomes, we used a Bonferroni correction factor of six to adjust the p-values for relationships with pFI (33).

Results

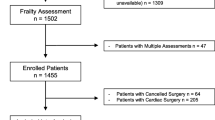

The general cohort sample included 7408 subjects (Figure 1). They were mostly older persons (mean±SD age, 74±7 yrs), mostly male, and spent a median of 5.1 days hospitalized for the index surgery (Table 2). The pFI ranged 0–0.68 with a mean±SD of 0.21±0.09. Among the six outcomes (Table 3), 0.6% of previously home-dwelling subjects were newly admitted or wait-listed for a nursing home within 180 days.

Analysis of that outcome of primary interest included 7303 subjects (Figure 1), of whom 43 experienced it at a median time of 89 days after index hospital admission (interquartile range 66–107 days). Each additional 0.1 unit increase in pFI was associated with a hazard ratio for new NH admission or wait-listing of 3.01 (95% C.I. 2.42–3.76; p<0.0006; Table 4). This cause-specific hazard ratio was virtually identical to that obtained taking account of death as a competing risk (34).

All five secondary postoperative outcomes were also associated with preoperative frailty (Table 4). This includes short-term (30-day) mortality, intermediate-term (90–180 day) mortality, and post-hospital utilization of outpatient physician visits, emergency department visits, and hospital-days. For both outpatient physician visits and hospital-days, the relationship with frailty was statistically nonlinear. However the former was effectively linear (eFigure 1A), while for the latter the relationship was relatively flat for pFI values from 0 to 0.2, increasing linearly thereafter (eFigure 1B).

Discussion

We found that frailty is a strong risk factor for home-dwelling people to require nursing home placement after elective surgery. Each rise in the McIsaac frailty scale of 0.1 units, or 1.1 standard deviation of its distribution in our sample, was associated with a 3-fold higher hazard for this outcome. Increasing frailty was also associated with higher mortality rates and medical resource use. Of note, the distribution of pFI in our subjects was similar to that in the original work in which it was described (26).

We identified 25 existing publications assessing whether frailty is related to postoperative discharge location (17, 19–21). Generally, but not universally, these reported significant associations between frailty and not being able to go back home after surgery. However, these all have important limitations which our study avoided. Only three limited consideration to people living in the community preoperatively (35–37). Only four distinguished discharge to NH from discharge to temporary non-home locations, such as rehabilitation facilities (19, 35, 36, 38). All 25 restricted consideration to immediate hospital discharge location, ignoring the possibility of posthospital recognition of the need for long-term placement; the relevance of this limitation is indicated by our finding that half of those newly entering nursing homes did so more than 80 days postoperatively. And none performed the statistical adjustments needed to address inflated Type I error rates from performing multiple comparisons (39, 40).

More generally, frailty has been associated with adverse outcomes in virtually every type of cohort assessed, including postoperatively (17), in patients with critical illness (41), chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes (42, 43), and in advanced age (44). McIsaac et al. demonstrated that the effect of frailty on death in elective surgical patients is largely related to higher rates of postoperative complications (18).

In addition to avoiding the above-mentioned methodologic problems of prior work, our study has salient strengths. It is a population-based study from a health region in a Canadian province over eight years, which assessed a range of relevant outcomes. Consistent with its underlying conceptual framework (14, 16), we analyzed frailty as a continuum, rather than the binary representation used in some prior studies. And finally, our analysis included robust adjustment for potential confounding variables, including patient demographics, socioeconomic status, and uniquely among existing studies, a measure of the degree of operative stress.

Our study also has limitations, of which foremost is the pFI frailty measure we used. Currently, the two principal clinical reference standard frailty constructs are the Frailty Phenotype (16), and deficit-counting method Frailty Index (14). As both require detailed clinical assessment, we instead used one of the claims-based measures that quantify frailty for large population-based datasets in which clinical assessment is infeasible. Such measures use diagnosis codes and health service claims, and like the clinical measures they relate to relevant outcomes (45). The pFI was developed in Canada for, and validated against, postoperative outcomes by McIsaac et al. (26). It is a composite including age, sex, living environment, socioeconomic status, comorbid conditions, prior hospitalizations and emergency department visits, certain medications, and characteristics of the index hospitalization. Though inclusion of homecare and some durable medical equipment improves correspondence of pFI with clinical frailty (46), pFI like other of its kind has differences from the clinical measures (46). While the few existing direct comparisons of claims-based with clinical measures have shown only modest correlations (45, 47), the correspondence between the Frailty Phenotype and Frailty Index is, in fact, only slightly higher (48). Nonetheless, we recognize the possibility that our findings would differ with use of an alternative measure. The main concern about using pFI, or any frailty measure that incorporates comorbid conditions, is that it misattributes effects of comorbidity to frailty. However, while clearly distinct, frailty and comorbidity have a complex bi-directional relationship, with some evidence that frailty may contribute to progression or even development of some comorbid conditions (49, 50). Indeed, it may be that much of the seemingly direct influence of comorbid conditions on some relevant outcomes is mediated by a common denominator of frailty.

Other limitations include the possibility that our findings might not generalize to other jurisdictions, and that as in all observational studies, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Finally, although our conceptual basis for including OSS as a covariate in our analysis was the assumption that it, rather than the specific surgical procedure, is a main influence on our outcomes, bias could have entered our results if there is substantial variation in outcomes across different procedures with the same OSS.

In light of the high value that most people place on independence (2–5), and their associated aversion to living in a nursing home (8–11), our primary result has important implications for anesthesia and surgical practice. Strong arguments follow that surgical candidates be evaluated for their degree of frailty, and that their informed consent include discussion of the possibility of survival with loss of independence (51). Although the absolute rate of this outcome was only 6 per 1000 procedures, that is much higher than the approximate rate of 3 anesthesia deaths per 100,000 (52), for which informed consent is universal. Especially for elective surgeries, as we have studied, routine assessment of frailty in the preoperative clinic setting is feasible (53). However, the small literature on informed consent for surgery demonstrates important deficiencies (54, 55), and we were unable to find any published information relating to how often the possibility of ending up in a nursing home is included in discussions on informed consent.

References

Ebell MH, Smith MA, Seifert DK, Polsinelli K. The Do-Not-Resuscitate order: outpatient experience and decision-making preferences. Journal of Family Practice 1990; 31: 630–636

Araujo IL, Castro MC, Daltro C, Matos MA. Quality of Life and Functional Independence in Patients with Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Knee Surg Relat Res 2016; 28: 219–224; DOI:https://doi.org/10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.3.219

Hofman CS, Makai P, Boter H, Buurman BM, de Craen AJ, Olde Rikkert MG, Donders R, Melis RJ. The influence of age on health valuations: the older olds prefer functional independence while the younger olds prefer less morbidity. Clin Interv Aging 2015; 10: 1131–1139; DOI:https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S78698

Martinez-Martin P, Prieto-Flores ME, Forjaz MJ, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Rojo-Perez F, Rojo JM, Ayala A. Components and determinants of quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Eur J Ageing 2012; 9: 255–263; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0232-x

Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. New England Journal of Medicine 2002; 346: 1061–1068; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa012528

Katz P. An international perspective on long term care: focus on nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2011; 12: 487–492

Nursing Home Care. 2020 [cited 2020 September 7]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/nursing-home-care.htm.

Mattimore TJ, Wenger NS, Desbiens NA, Teno JM, Hamel MB, Liu H, Califf R, Connors AF, Lynn J, Oye RK. Surrogate and Physician Understanding of Patients’ Preferences for Living Permanently in a Nursing Home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1997; 45: 818–824; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01508.x

Long-Term Care in Canada: Three-quarters say significant change is needed; only one-in-five believe it will happen. 2021 [cited 2021 December 9]. Available from: https://angusreid.org/canada-long-term-care-policy/.

Jang Y, Rhee MK, Cho YJ, Kim MT. Willingness to Use a Nursing Home in Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Health 2019; 21: 668–673; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0792-8

Dong X, Wong BO, Yang C, Zhang F, Xu F, Zhao L, Liu Y. Factors associated with willingness to enter care homes for the elderly and pre-elderly in west of China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e23140; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000023140

Informed Consent. 2022 [cited 2022 February 15]. Available from: https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/serve/docs/ela/goodpracticesguide/pages/communication/Informed_Consent/informed_consent-e.html.

Abaunza H, Romero K. Elements for adequate informed consent in the surgical context. World J Surg 2014; 38: 1594–1604; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2588-x

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173: 489–495; DOI:173/5/489 [pii] https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Walston JD. Frailty. In: Schmade KE, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2020.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M146–156; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

Alkadri J, Hage D, Nickerson LH, Scott LR, Shaw JF, Aucoin SD, McIsaac DI. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preoperative Frailty Instruments Derived From Electronic Health Data. Anesth Analg 2021; 133: 1094–1106; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005595

McIsaac DI, Aucoin SD, Bryson GL, Hamilton GM, Lalu MM. Complications as a Mediator of the Perioperative Frailty-Mortality Association. Anesthesiology 2021; 134: 577–587; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003699

Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, Kim KI, Hwang DW, Kang SB, Kim CH. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg 2014; 149: 633–640; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.241

Ambler GK, Brooks DE, Al Zuhir N, Ali A, Gohel MS, Hayes PD, Varty K, Boyle JR, Coughlin PA. Effect of frailty on short- and mid-term outcomes in vascular surgical patients. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 638–645; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9785

Sikder T, Sourial N, Maimon G, Tahiri M, Teasdale D, Bergman H, Fraser SA, Demyttenaere S, Bergman S. Postoperative Recovery in Frail, Pre-frail, and Non-frail Elderly Patients Following Abdominal Surgery. World J Surg 2019; 43: 415–424; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4801-9

Manitoba Population Research Data Repository. 2021 [cited 2020 July 11]. Available from: https://umanitoba.ca/manitoba-centre-for-health-policy/data-repository.

Manitoba Population Report: June 1, 2016. 2016 [cited 2018 January 24]. Available from: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/population/pr2016.pdf.

Discharge Abstract Database metadata (DAD). 2020 [cited 2020 August 17]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/discharge-abstract-database-metadata-dad.

Shinall MC, Jr., Arya S, Youk A, Varley P, Shah R, Massarweh NN, Shireman PK, Johanning JM, Brown AJ, Christie NA, Crist L, Curtin CM, Drolet BC, Dhupar R, Griffin J, Ibinson JW, Johnson JT, Kinney S, LaGrange C, Langerman A, Loyd GE, Mady LJ, Mott MP, Patri M, Siebler JC, Stimson CJ, Thorell WE, Vincent SA, Hall DE. Association of Preoperative Patient Frailty and Operative Stress With Postoperative Mortality. JAMA Surg 2019: e194620; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.46202755273 [pii]

McIsaac DI, Wong CA, Huang A, Moloo H, van Walraven C. Derivation and Validation of a Generalizable Preoperative Frailty Index Using Population-based Health Administrative Data. Annals of Surgery 2019; 270: 102–108; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002769

Hirdes JP, Mitchell L, Maxwell CJ, White N. Beyond the ‘Iron Lungs of Gerontology’: Using Evidence to Shape the Future of Nursing Homes in Canada Canadian Journal on Aging 2011; 30: 371–390; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000304

Garland A, Olafson K, Ramsey C, Yogendren M, Fransoo R. Distinct Determinants of Long-term and Short-term Survival in Critical Illness. Intensive Care Medicine 2014; 40: 1097–1105; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3348-y

Marrie RA, Dawson NV, Garland A. Quantile Regression and Restricted Cubic Splines are Useful for Exploring Relationships Between Continuous Variables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2009; 62: 510–516; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.015

Chateau D, Metge C, Prior H, Soodeen R. Learning from the census: the Socioeconomic Factor Index (SEFI) and health outcomes in Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2012; 103: S23–S27; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403825

Babyak MA. What You See May Not Be What You Get: A Brief, Nontechnical Introduction to Overfitting in Regression-Type Models. Psychosomatic Medicine 2004; 66: 411–421; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9

Dunteman GH. Principal Components Analysis. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 1989; 69

Statistical tests: multiple comparisons. 2020 [cited 2021 June 19]. Available from: http://sia.webpopix.org/statisticalTests2.html.

Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the Analysis of Survival Data in the Presence of Competing Risks. Circulation 2016; 133: 601–609; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719

McIsaac DI, Beaule PE, Bryson GL, Van Walraven C. The impact of frailty on outcomes and healthcare resource usage after total joint arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B: 799–805; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.37124

McIsaac DI, Moloo H, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. The Association of Frailty With Outcomes and Resource Use After Emergency General Surgery: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Anesth Analg 2017; 124: 1653–1661; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001960

George EL, Chen R, Trickey AW, Brooke BS, Kraiss L, Mell MW, Goodney PP, Johanning J, Hockenberry J, Arya S. Variation in center-level frailty burden and the impact of frailty on long-term survival in patients undergoing elective repair for abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2020; 71: 46–55 e44; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.074

Asemota AO, Gallia GL. Impact of frailty on short-term outcomes in patients undergoing transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. J Neurosurg 2019; 132: 360–370; DOI:https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.8.JNS181875

Chen SY, Feng Z, Yi X. A general introduction to adjustment for multiple comparisons. J Thorac Dis 2017; 9: 1725–1729; DOI:https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.05.34

Borochin P, Krieger A. Measuring the Effects of Multiplicity:A Study of Multiple Comparison Procedures in Multiple Linear Regression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2004.

Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, Rolfson DB, Tsuyuki RT, Baig N, Artiuch B, Ibrahim Q, Stollery DE, Rokosh E, Majumdar SR. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ 2014; 186: E95–102; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.130639

Kusunose M, Sanda R, Mori M, Narita A, Nishimura K. Are frailty and patient-reported outcomes independent in subjects with asthma? A cross-sectional observational study. Clin Respir J 2021; 15: 216–224; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.13287

Sable-Morita S, Tanikawa T, Satake S, Okura M, Tokuda H, Arai H. Microvascular complications and frailty can predict adverse outcomes in older patients with diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2021; 21: 359–363; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14142

Ensrud KE, Kats AM, Schousboe JT, Taylor BC, Cawthon PM, Hillier TA, Yaffe K, Cummings SR, Cauley JA, Langsetmo L, Study of Osteoporotic F. Frailty Phenotype and Healthcare Costs and Utilization in Older Women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66: 1276–1283; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15381

Shashikumar SA, Huang K, Konetzka RT, Joynt Maddox KE. Claims-based Frailty Indices: A Systematic Review. Med Care 2020; 58: 815–825; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001359

Kim DH. Measuring Frailty in Health Care Databases for Clinical Care and Research. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2020; 24: 62–74; DOI:https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.20.0002

Kim DH, Patorno E, Pawar A, Lee H, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ. Measuring Frailty in Administrative Claims Data: Comparative Performance of Four Claims-Based Frailty Measures in the U.S. Medicare Data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020; 75: 1120–1125; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz224

Kim DJ, Massa MS, Clarke R, Scarlett S, O’Halloran AM, Kenny RA, Bennett D. Variability and agreement of frailty measures and risk of falls, hospital admissions and mortality in TILDA. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 4878; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08959-7

Espinoza SE, Quiben M, Hazuda HP. Distinguishing Comorbidity, Disability, and Frailty. Curr Geriatr Rep 2018; 7: 201–209; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-018-0254-0

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59: 255–263; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013; 381: 752–762; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

Bainbridge D, Martin J, Arango M, Cheng D, Evidence-based Peri-operative Clinical Outcomes Research G. Perioperative and anaesthetic-related mortality in developed and developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 380: 1075–1081; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60990-8

Amrock LG, Neuman MD, Lin HM, Deiner S. Can routine preoperative data predict adverse outcomes in the elderly? Development and validation of a simple risk model incorporating a chart-derived frailty score. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 219: 684–694; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.04.018

Hanson M, Pitt D. Informed consent for surgery: risk discussion and documentation. Can J Surg 2017; 60: 69–70; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.004816

St John ER, Scott AJ, Irvine TE, Pakzad F, Leff DR, Layer GT. Completion of handwritten surgical consent forms is frequently suboptimal and could be improved by using electronically generated, procedure-specific forms. Surgeon 2017; 15: 190–195; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2015.11.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest and source of funding: All authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest. This work was supported by research grants from the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine’s Oversight and Advisory Committee at the University of Manitoba.

Ethical standard: This study, approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba (HS24056), did not require subject consent as it utilized existing, deidentified, data.

Online Supplemental Content

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Garland, A., Mutter, T., Ekuma, O. et al. The Effect of Frailty on Independent Living After Surgery: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. J Frailty Aging 13, 57–63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2023.27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2023.27