Abstract

With increasing regulation of IT security, the relevance of contract drafting also increases. Outsourcing and cloud contracts must strike the right balance between customer-specific IT security requirements and established service provider standards.

Zusammenfassung

Mit zunehmender Regulierung der IT-Sicherheit steigt auch die Relevanz der Vertragsgestaltung. Outsourcing- und Cloud-Verträge müssen die richtige Balance zwischen kundenspezifischen IT-Sicherheitsanforderungen und etablierten Dienstleisterstandards finden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: the need for contract drafting

The use of cloud computing has steadily increased in recent years and has become an established standard for information technology (IT) and outsourcing services [1, p. 11]. Especially in the area of cloud computing, an increasing tension can be observed between standardised processes of the cloud service provider and individual customer requirements [2, para. 141].

On the one hand, cloud business models take advantage of the principle of scalability. In order to be able to offer scalable cloud services, IT providers strive to standardise underlying processes as far as possible and to make them customer-neutral. This applies not only to the technical processes, but also to contract management: providers of cloud services are particularly keen to use uniform contract terms. [3, para. 10].

On the other hand, customers place themselves in a special dependency on the outsourcing provider [4, p. 470]. In order to mitigate the risks of this lock-in effect, many companies aim to implement individual special rights in the outsourcing contract. In addition, companies in regulated industries are increasingly forced by law to impose certain minimum requirements vis-à-vis IT providers. Depending on the national jurisdiction, this applies in particular to the health, food, communications, transport and energy sectors, but also to the financial sector. The cybersecurity strategy in the European Union (EU) and in Germany (see Sect. “Critical infrastructure (KRITIS)” below) clearly aims to raise the level of cyber resilience of all relevant sectors, public and private, that perform an important function for the economy and society [5, p. 5]. In particular, the EU Commission proposal for an NIS Directive 2.0 [6, p. 9] expands the scope of the current regulation to important entities operating in a number of new sectors. To make matters worse, regulatory requirements vary considerably both nationally and in individual economic sectors. Sectors that are already subject to strict regulation in general are now also increasingly regulated from a cybersecurity perspective [7, p. 3]. In addition, the requirements are enforced at different levels: through hard top down regulation, competitors, or liability regulations [8, p. 575]. This leads to companies having different requirements for their IT projects, especially if there are no or few industry-specific specifications. The result is that when it comes to cybersecurity, there is a patchwork of diverse customer-specific requirements worldwide.

How can this growing tension between established contractual standards of IT service providers and the different requirements of customers be resolved? In practice, the balance can usually only be achieved through customised contracts that address each requirement appropriately. Just as in the development of software, the industry-specific standards must be programmed into the contract. Precisely this is a central reason for the increasing importance of contract design for cybersecurity.

2 General guidance on drafting of contractual cybersecurity provisions

For the efficient drafting of contractual documents under IT security law, we recommend the following procedure (irrespective of the jurisdiction):

Step 1: identifying relevant legal requirements

In a first step, the relevant IT security legal requirements are identified and clustered. This involves national (possibly international) laws and regulatory requirements. The aim of the first step is to understand not only which, but also how many separate contractual annexes are needed on the topic of cybersecurity.

If a situation is based on several different sets of laws, the following general rule applies: The more the protective purposes, the legal terminology and the competences of the respective supervisory authorities differ from each other, the more advisable it is to separate them into different contractual annexes. In this case, a separate cybersecurity annex is created for each set of laws. This modular contract structure has the advantage that it is possible to react efficiently to legal changes by only having to adapt a single contract annex instead of the entire IT contract. If the regulatory topics are each dealt with in a separate annex, the intention of the parties is already formally clear and compliance with legal requirements can be easily proven. Finally, the different regulatory complexes should be assessed and prioritised. Regulatory annexes should have priority over the main contract (lex specialis derogat legi generali). The contractual ranking within the regulatory contract annexes is often based on the urgency, i.e. the threatened legal consequences (e.g. fines, penalties, withdrawal of the operating licence, official measures, etc.) in the event of non-implementation of an IT security law requirement. Prioritising the regulatory complexes can also serve to efficiently allocate resources for contract negotiation and compliance measures.

Step 2: implement mandatory legal requirements

In a second step, the mandatory legal requirements must be implemented contractually. The decisive factor here is whether the respective legal or official requirements stipulate certain minimum contents for the contract design: This often involves the agreement of certain control rights and reservations of consent on the part of the customer, for example with regard to the outsourcing to sub-service providers.

In order to avoid risks, the wording of the contractual provisions should reflect the official wording of the respective law as closely as possible. This allows for a dynamic interpretation that is oriented towards the respective current requirements. When using clauses that deviate from the requirements of the respective law or restrict the statutory minimum regulations, there is often the risk that the supervisory authority or court could consider the agreement as a whole to be invalid. In particular, the regulatory terminology should be used one-to-one in the contract—as far as this makes sense. Otherwise, there is a risk of (unnecessarily) creating or increasing terminological ambiguities and therefore inadequately implementing legal requirements.

Step 3: optional contractual provisions

In a third step, it is possible to agree on further contractual provisions, e.g. to address project- or customer-specific particularities or to complement the implementation of mandatory legal requirements.

There is often leeway on commercial issues, i.e. which party bears the costs of implementing the IT security requirements. Expenses for individual cybersecurity measures (e.g. customer audits) are often allocated to the regulated customer, unless these measures are based on a breach by the service provider. For multi-client providers and other standard products, customers often expect the IT provider to bear the costs of standard reports, compliance measures and the implementation of changed laws.

In addition, indeterminate technical legal terms should be concretised as far as possible with effect between the contracting parties, e.g. by referring to relevant technical standards and recognised practical guidelines. Furthermore, obligations to provide evidence and documentation, certificates and test reports offer simplifications.

Other regulatory topics, which are often optional depending on the jurisdiction, are indemnity rules, guarantees and the agreement of contractual penalties. Governance agreements are also recommended in order to efficiently organise the cooperation of the parties with regard to cybersecurity, e.g. the regulation of concrete processes, competences, contact persons and measures in the event of any IT security incidents.

3 Best practices: outsourcing and cloud computing in the financial sector in Germany

In the following, the guidance presented above will now be illustrated using the concrete example of the financial sector in Germany:

3.1 Financial regulatory law

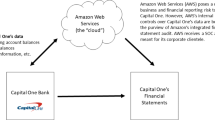

Billions of people around the world use different financial services every day. The dependence of the economic system on these services has led to comprehensive regulation worldwide in general and increasing regulation in the area of IT. The main purpose of the financial supervisory regulations on digital outsourcing is to prevent institutions or insurance companies from losing the ability to control or steer, as this could limit or withdraw control by the supervisory authorities [9, para. 2.] A particular focus of the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) is on the shift of business critical processes to the cloud [10].

Identifying relevant legal requirements

The high penetration of standards in the financial sector makes the legal situation regarding IT security confusing. Institutions (credit institutions and financial services institutions) and insurance companies in Europe are regulated by very similar, yet different regimes. With regard to IT outsourcing, institutions must comply with the requirements pursuant to Sec. 25a, 25b German Banking Act (Kreditwesengesetz, KWG), European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines on outsourcing [11], the German banking supervisory requirements for IT (Bankaufsichtliche Anforderungen an die IT, BAIT) [12], German minimum requirements for risk management (Mindestanforderungen an das Risikomanagement, MaRisk) [13], among others. Insurance companies are subject to comparable requirements according to Sec. 32 German Insurance Supervision Act (Versicherungsaufsichtsgesetz, VAG), Solency II [14], Art. 274 Delegated Regulation [15], European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) Guidelines on outsourcing to cloud service providers [16], minimum requirements for the business organization of insurance companies (Mindestanforderungen an die Geschäftsorganisation von Versicherungsunternehmen, MaGO) [17], regulatory requirements for insurance IT (Versicherungsrechtliche Anforderungen an die IT, VAIT) [18]. It should be particularly emphasised that the guidelines of the European and German supervisory authorities provide detailed specifications of the legal requirements. In particular, BaFin has published a Guidance on outsourcing to cloud service providers [10] to make its regulatory view transparent.

The decisive prerequisite for the aforementioned standards is the existence of an “outsourcing” case. This is determined, among other things, by the extent to which the service to be outsourced is functionally related to specific processes and activities of the institution or the insurance company as such. The duration and frequency of the use of the service provider can also significantly influence the classification [9, para. 16],[17, para. 239]. The actual relevance of the IT service for the institution or insurance company and the consequences of failures are decisive. The disruption of services that are not specific to the institution or insurance company—such as the purchase of universal organisational tools—can also have significant disruptive effects. In contrast, the one-off purchase of hardware and/or software can also be classified as an outsourcing if the function of the software is precisely and closely related to the risks of the institution or insurance company [18, para. 70]. Even higher requirements apply when functions that are critical to the provision of services to the institution’s or insurance company’s clients are outsourced [19, para. 60]. This is particularly the case for key functions that give rise to regulatory risks, such as the risk management function, compliance function, internal audit function or, in the case of insurance, the actuarial function [20, p. 535].

Contractual implementation (“regulatory annex”)

Among other things, institutions [11, para. 87 lit. a] and insurers [19, Guideline 11] must contractually ensure within the written outsourcing agreement that the service provider grants them and their competent authorities, including resolution authorities, and any other person appointed by them or the competent authorities full access to all relevant business premises (e.g. head offices and operation centres), including the full range of relevant devices, systems, networks, information and data used for providing the outsourced function, including related financial information, personnel and the service provider’s external auditors (“access and information rights”) [19, Guideline 11]. Cloud providers can contractually establish a standardised information and control procedure, e.g. with notice periods, confidentiality requirements for the actual auditors, documentation obligations and cost regulations. Institutions may use pooled audits (i.e. audits performed jointly with other customers of the same cloud service provider) [19, Guideline 11] to use audit resources more efficiently and to decrease the organisational burden on both the customer and the service provider [11, para. 91 lit. a]. Particularly for the outsourcing of critical or important functions, however, a full and unrestricted right to information must be ensured. As a rule, it is also agreed that the control rights continue to exist for a certain period of time after the termination of the service relationship. This is also intended to enable a later review of regulatory requirements [2].

The use of subcontractors is in natural tension with the objective of confidentiality. Due to the lack of a contractual relationship with the subcontractor, the cloud customer often has no overview of the scope of the subcontracting [2]. The outsourcing agreement should stipulate that the use of subcontractors is only possible with prior consent of the regulated customer [13]. In addition, it should be regulated, for example, whether the subcontracting of critical or essential functions of the same is permissible and that subcontracting only takes place if the subcontractor undertakes to comply with all applicable laws and contractual obligations [11, para. 79 lit. a], [19, Guideline 13]. In particular, the IT service provider must be contractually obliged to “pass on” all IT security requirements to which it is subject (e.g. confidentiality obligations, audit and control rights) to its subcontractor.

Financial Institutions should ensure that they are able to exit outsourcing arrangements without undue disruption to their business activities, without limiting their compliance with regulatory requirements and without any detriment to the continuity and quality of its provision of services to customers. To achieve this, they should, in particular, develop and implement exit plans that are comprehensive, documented and, where appropriate, sufficiently tested (e.g. by carrying out an analysis of the potential costs, impacts, resources and timing implications of transferring an outsourced service to an alternative provider) [11, para. 107]. In order to mitigate the dependency on the outsourcing provider and to avoid lock-in effects, a contractually agreed exit management procedure is therefore essential for regulated customers. Here, the IT service provider undertakes, among other things, to hand over data and documents in good time in order to enable the customer to provide the previously outsourced services itself or to have them provided by a successor contractor [19, Guideline 15]. An important requirement for many customers is the contractual right to exercise a grace period (usually 6–12 months) during which the service provider must continue to provide the services after termination at the request of the customer [21, para. 324]. Often, a contingency plan and an exit plan are also agreed to enable migration to a successor provider. In the case of outsourcing, a contractual option to take over hardware and software may also be considered.

3.2 Critical infrastructure (KRITIS)

Identifying relevant legal requirements

In addition to the special legal requirements for the financial sector, institutions and insurance companies are additionally confronted with detailed requirements for the organisation and architecture of their IT infrastructure if they are “of high importance for the functioning of the community” [22, Sec. 2 para. 10]. Across Europe as well as across industries, companies that operate critical infrastructures (KRITIS) must take appropriate measures to secure their IT infrastructure on the basis of Directive (EU) 2016/1148 (NIS Directive [23]) and provide the supervisory authority with appropriate evidence of doing so. In the case of violations, companies currently face fines of up to EUR 100,000. This framework is expected to be significantly tightened again in Germany by the reform of the national IT Security Act [24] and raised to EUR 20 million [24, Sec. 14 para. 5 sentence 3]. The relevance of these special-law requirements is expected to increase due to the planned inclusion of an additional sector [24, Sec. 2 para. 10] and “companies in the special public interest” [24, Sec. 2 para. 14] in the scope of the law (a comprehensive overview of the reform is provided in [25]).

When is a company considered KRITIS? In Germany, the legislator has formed certain threshold values for this purpose, which, when reached, make the institutions or insurance companies subject to the legal requirements. [26] This approach meets the objective of IT security law only to a limited extent, since the failure of the IT systems of many “small” institutions or insurance companies that are below the threshold can have just as devastating (or even worse) consequences as the failure of the IT of a “large” one. For the institutions and insurance companies, however, the thresholds offer a certain degree of legal certainty.

Contractual implementation (“KRITIS annex”)

The contract drafting for digital outsourcing projects is highly relevant because the operators of critical infrastructures, as addressees of the legal requirements, remain responsible for ensuring the security of their IT systems and cannot leave it solely to their service providers. The outsourcing agreement thus also serves the supervisory authority as a benchmark for the extent to which the company has taken appropriate organisational and technical precautions.

The objective of the Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive [23] is based on the four elements of availability, authenticity, integrity and confidentiality of information technology systems already known from data protection law, Art. 4 para. 2 NIS Directive [23] (see also [22, Sec. 8a para. 1]). The vague wording to take “appropriate measures” (cf. Art. 14 para. 1 NIS Directive [23]) takes account of constant technical change and can also be found in other regulations at the interface of technology and financial law (e.g. regarding the authentication of payment transactions, see Art. 97 para. 3 of the Payment Services Directive [PSD2]; [27, 28, p. 396]). Therefore, it makes sense to subdivide the structure of the IT security annex accordingly. In terms of content, the annex should be closely oriented to recommendations and guidelines that concretise standards. In Germany, the “Best Practice Recommendations for Requirements for Suppliers to Ensure Information Security in Critical Infrastructures” of the UP KRITIS working group (a cooperation between operators of critical infrastructures, their associations and the responsible government agencies) should be used, which precisely specify the contract topics [29].

Since time is a decisive factor in the defence against cyber-attacks, the service provider’s response and notification obligations should also be made dependent on the criticality of the disruption and certain groups of cases should be anticipated. The time periods for the remediation of vulnerabilities in the contractual software can be clearly determined by reference to the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) and the determination of the patch delivery times in relation to the respective Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) Score [30]. Last but not least, the contractual agreements should also consider the strategic orientation in the event of cyber-attacks (creation of threat models, clarification of responsibilities and processes, communication).

The threats to IT systems are constantly changing [31]. The specification of legal IT security requirements, in turn, is necessarily based on the state of the art of IT technology at the time of the conclusion of the contract. In order to contractually reflect future threats to IT security, the agreements should be as flexible as possible. This can best be achieved by dynamically referring to the latest recommendations, assistance and best practice guidelines from independent organisations dedicated to the topic of IT security, such as the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) [32], which regularly publishes recommendations for action on web application security.

Finally, the KRITIS annex should be enriched with individual requirements, such as:

-

Physical data centre requirements (protection against natural hazards such as fire, water or earthquakes, burglary protection, securing supply technology)

-

Personnel and organisation measures (regular training, security checks of employees, obligation of employees to confidentiality, access management)

-

Infrastructure requirements (use of hardened operating systems, firewalls, secure remote connections)

-

Concrete specifications for the respective software (use of program libraries, code review, testing)

Internal IT security guidelines and the weak points identified in the course of a security analysis can serve as a starting point for the draft of the individual requirements. A high degree of individuality also shows the supervisory authority that the outsourcing institution has dealt intensively with the topic of IT security.

3.3 Data protection law

Almost every digital outsourcing of institutions or insurance companies also concerns the (electronic) processing of personal data.

Identifying relevant legal requirements

Cloud computing is usually data processing on behalf of a third party within the meaning of Art. 28 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [33]. Therefore, the IT service provider must provide sufficient guarantees that appropriate technical and organisational measures (TOMs) are implemented in such a way that the processing is carried out in compliance with the requirements of the GDPR and ensures the protection of the rights of the data subject. Pursuant to Art. 28 (3) GDPR, the processing by the processor must be carried out on the basis of a contract binding the processor in relation to the controller and specifying the subject matter and duration of the processing, the nature and purpose of the processing, the type of personal data, the categories of data subjects and the obligations and rights of the controller.

Contractual implementation (“DPA annex”)

In addition to the main IT contract and other regulatory annexes, the conclusion of a Data Processing Agreement (DPA) is typically required.

Precise contractual regulations help to assign responsibility in the event of breaches and can thus noticeably minimise the liability risks of the customer. In the DPA, it is therefore recommended to oblige the processor to evaluate the IT security risks and to derive concrete security measures from this (see also paragraph 6 (2) and (3) of the Danish supervisory authority’s draft standard contractual clauses, which have been included in the European Data Protection Board’s register of decisions [34]). The necessary level of detail of these measures is determined by the risks for the person affected by the data processing [35, para. 81, 82]. The customer should therefore carry out its own supplementary risk-based assessment in order to be able to evaluate the measures submitted by the processor with regard to the necessary scope. Subsequently, the concrete technical and organisational measures can then be attached to the data processing agreement.

In view of the threat of fines of up to EUR 400 million or 4% of the global annual turnover (Art. 83 GDPR), it is regularly in the interest of the customer to contractually commit the IT service provider to specific TOMs, compliance with which the customer can then monitor and, if necessary, prove to the data protection authority. In contrast, cloud providers would like to reserve the right to continuously adapt TOMs to technical developments. A compromise may be to make the specification of concrete TOMs dynamic, but to prescribe certain minimum requirements oriented to the respective state of the art, as well as documentation obligations [4]. In practice, different catalogues of measures are regularly applied [36], such as specific ISO standards of the International Organisation for Standardisation (e.g. ISO 27001), the corresponding DIN standards of the German Institute for Standardisation, or the IT-Grundschutz-Kompendium published by the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) [37]. In particular, the processor should be contractually obliged to document and report any changes to the TOM to the controller.

4 Conclusion

Contractual regulations in the area of cybersecurity are of increasing relevance for almost all conceivable types of contracts. Through contracts, the existing legal uncertainties and risks can be effectively allocated between contractual partners.

European and German legislators are imposing ever stricter requirements on the legal outsourcing of IT services, e.g. in the financial sector. Thus, in the context of outsourcing and cloud projects, an increasing tension can be observed between the established contractual standards of the IT service providers and the customer-specific IT security requirements. In practice, this tension can only be resolved through customised contract annexes that adequately address all customer requirements.

Best practices for the drafting of cybersecurity annexes have emerged in recent times. In particular, specific sectoral laws, official guidelines of regulatory authorities as well as technical standards provide important guidance for contract drafting. As cybersecurity may be addressed by several laws and enforced by different authorities (e.g. financial regulatory law, critical infrastructure law, data protection law), it may be advisable to conclude different contractual cybersecurity annexes for each area.

References

Kriterienkatalog Cloud Computing C5:2020 des Bundesamts für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik (Criteria catalog Cloud Computing C5:2020 of the German Federal Office for Information Security). https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/BSI/CloudComputing/Anforderungskatalog/2020/C5_2020.pdf;. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Pour Rafsendjani, Bomhard (2020) 9 IT-Sicherheit im Zivilrecht und in der Vertragsgestaltung. In: Hornung, Schallbruch (eds) Praxishandbuch IT-Sicherheitsrecht

Strittmatter (2019) 22 Cloud Computing. In: Auer-Reinsdorff, Conrad (eds) Handbuch IT- und Datenschutzrecht, 3rd edn

Thalhofer (2019) Vertragspraxis und IT-Sicherheit – aktuelle Herausforderungen und mögliche Lösungen. 16. Deutscher IT-Sicherheitskongress des BSI

The EU’s cybersecurity strategy for the digital decade, JOIN(2020) 18 final. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/eus-cybersecurity-strategy-digital-decade. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and the Council on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148, COM(2020) 823 final. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/proposal-directive-measures-high-common-level-cybersecurity-across-union. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Dreher, Gerigk (2020) IT- und Cloud-Dienste – Versicherungsaufsicht bei der Ausgliederung

Riehm, Meier (2020) Rechtliche Durchsetzung von Anforderungen an die IT-Sicherheit. Multimedia und Recht MMR 2020:571–575

Lensdorf (2020) 25b KWG. In: Schuster, Grützmacher (eds) IT-Recht Kommentar

BaFin Merkblatt – Orientierungshilfe zur Auslagerung an Cloud-Anbieter, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (Information sheet—Guidance on outsourcing to cloud providers, German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority). https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Merkblatt/BA/dl_181108_orientierungshilfe_zu_auslagerungen_an_cloud_anbieter_ba_en.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

European Banking Authority (EBA) Guidelines on outsourcing arrangements. https://www.eba.europa.eu/regulation-and-policy/internal-governance/guidelines-on-outsourcing-arrangements. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

BaFin-Rundschreiben 10/2017 (BA) „Bankaufsichtliche Anforderungen an die IT“ (Banking supervisory requirements for IT). https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Rundschreiben/dl_rs_1710_ba_BAIT.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

BaFin-Rundschreiben 09/2017 „Mindestanforderungen an das Risikomanagement“ (Minimum requirements for risk management). https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/DE/Rundschreiben/2017/rs_1709_marisk_ba.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Directive 2009/138/EC oft he European Parliament and oft eh Council of 25 November 2009 on the taking-up and pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32009L0138. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35 of 10 October 2014 supplementing Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the taking-up and pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R0035. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

EIOPA-BoS-20-002 31 01 2020 Final Report on public consultation No. 19/270 on Guidelines on outsourcing to cloud service providers. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/content/guidelines-outsourcing-cloud-service-providers_en. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

BaFin-Rundschreiben 2/2017 (VA) „Mindestanforderungen an die Geschäftsorganisation von Versicherungsunternehmen“ (Minimum requirements for the business organization of insurance companies). https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/DE/Rundschreiben/2017/rs_1702_mago_va.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

BaFin-Rundschreiben 10/2018 (VA) „Versicherungsrechtliche Anforderungen an die IT“ (Regulatory requirements for insurance IT). https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Rundschreiben/dl_rs_1810_vait_va.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), Guidelines on System of Governance. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/content/guidelines-system-governance_en. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Dahmen (2019) Auslagerungen an Cloud-Dienste. Z Bank Kapitalmarktr BKR 2019:533–540

Bräutigam (2019) Teil 13 Vertragsgestaltung. In: Bräutigam (ed) IT-Outsourcing und Cloud-Computing, 4th edn

Gesetz über das Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik (German Federal Office for Information Security Act)

Directive (EU) 2016/1148of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2016 concerning measures for a high common level of security of network and information systems across the Union

Draft of a second act to enhance the security of information technology systems. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/gesetzgebungsverfahren/DE/entwurf-zweites-it-sicherheitsgesetz.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Kipker, Scholz (2019) Das IT-Sicherheitsgesetz 2.0. Neue Rahmenbedingungen für die Cybersicherheit in Deutschland. Multimedia und Recht MMR 2019:431–435

Verordnung zur Bestimmung Kritischer Infrastrukturen nach dem BSI-Gesetz (Decree on the designation of critical infrastructures according to the German Federal Office for Information Security Act)

Directive (EU) 2015/2366of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015on payment services in the internal market, amending Directives 2002/65/EC, 2009/110/EC and 2013/36/EU and Regulation (EU) No 1093/2010, and repealing Directive 2007/64/EC (Text with EEA relevance)

Kunz (2018) Rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen für Mobile Payment – Ein Blick auf die Anforderungen zur starken Kundenauthentifizierung. Compliance Berater 2018:393–398

https://www.kritis.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/Kritis/DE/Anforderungen_an_Lieferanten.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

https://www.imperva.com/learn/application-security/cve-cvss-vulnerability/. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

McAfee labs 2020 threats predictions report. https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/other-blogs/mcafee-labs/mcafee-labs-2020-threats-predictions-report/. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Overview OWASP projects. https://owasp.org/projects/. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Koglin (2018) In: Koreng, Lachenmann (eds) Formularhandbuch Datenschutzrecht, 2nd edn

https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/edpb/files/files/file2/dk_sa_standard_contractual_clauses_january_2020_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Hartung (2020) Art. 28 DS-GVO. In: Kühlung, Buchner (eds) Datenschutz-Grundverordnung, Bundesdatenschutzgesetz: DS-GVO / BDSG

Klug (2018) Art. 28 DS-GVO. In: Gola (ed) Datenschutz-Grundverordnung, 2nd edn

IT-Grundschutz-Kompendium (Edition 2021). https://www.bsi.bund.de/DE/Themen/Unternehmen-und-Organisationen/Standards-und-Zertifizierung/IT-Grundschutz/IT-Grundschutz-Kompendium/it-grundschutz-kompendium_node.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2021

Funding

We acknowledge support for the Open Access Fee by University of Passau (University Library Publication Fund)

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bomhard, D., Daum, A. Cybersecurity in outsourcing and cloud computing: a growing challenge for contract drafting. Int. Cybersecur. Law Rev. 2, 161–171 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1365/s43439-021-00029-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1365/s43439-021-00029-4