Abstract

Background

Vast differences in barriers to care exist among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) groups and may manifest as disparities in stage at presentation and access to treatment. Thus, we characterized AANHPI patients with stage 0–IV colon cancer and examined differences in (1) stage at presentation and (2) time to surgery relative to white patients.

Patients and Methods

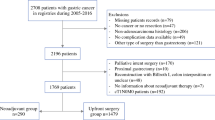

We assessed all patients in the National Cancer Database (NCDB) with stage 0–IV colon cancer from 2004 to 2016 who identified as white, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Native Hawaiian, Korean, Vietnamese, Laotian, Hmong, Kampuchean, Thai, Asian Indian or Pakistani, and Pacific Islander. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression defined adjusted odds ratios (AORs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI), of (1) patients presenting with advanced stage colon cancer and (2) patients with stage 0–III colon cancer receiving surgery at ≥ 60 days versus 30–59 days versus < 30 days postdiagnosis, adjusting for sociodemographic/clinical factors.

Results

Among 694,876 patients, Japanese [AOR 1.08 (95% CI 1.01–1.15), p < 0.05], Filipino [AOR 1.17 (95% CI 1.09–1.25), p < 0.001], Korean [AOR 1.09 (95% CI 1.01–1.18), p < 0.05], Laotian [AOR 1.51 (95% CI 1.17–1.95), p < 0.01], Kampuchean [AOR 1.33 (95% CI 1.04–1.70), p < 0.01], Thai [AOR 1.60 (95% CI 1.22–2.10), p = 0.001], and Pacific Islander [AOR 1.41 (95% CI 1.20–1.67), p < 0.001] patients were more likely to present with more advanced colon cancer compared with white patients. Chinese [AOR 1.27 (95% CI 1.17–1.38), p < 0.001], Japanese [AOR 1.23 (95% CI 1.10–1.37], p < 0.001], Filipino [AOR 1.36 (95% CI 1.22–1.52), p < 0.001], Korean [AOR 1.16 (95% CI 1.02–1.32), p < 0.05], and Vietnamese [AOR 1.55 (95% CI 1.36–1.77), p < 0.001] patients were more likely to experience greater time to surgery than white patients. Disparities persisted when comparing among AANHPI subgroups.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal key disparities in stage at presentation and time to surgery by race/ethnicity among AANHPI subgroups. Heterogeneity upon disaggregation underscores the importance of examining and addressing access barriers and clinical disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With over 100,000 new cases in 2021 and a 5-year survival rate of 63%,1 colon cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies in the USA, as well as the second-leading cause of cancer-related death. However, the burden of disease is not borne equally: vulnerable populations often experience barriers to colon cancer screening, receive treatment at lower rates, and face greater mortality.2,3 Such disparities have been identified on the basis of socioeconomic status,4 insurance coverage,5 gender,6 age,7 and various other sociodemographic factors. Colon cancer disparities among racial and ethnic minority groups, in particular, have been studied along with the differential risk factors and barriers in accessing care that produce these disparities.8,9 With Black Americans facing among the highest mortality rates from colon cancer, much of the literature on racial health disparities has understandably focused on this patient population. Notably less is known about presentation and treatment disparities among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) patients with colon cancer.

On average, AANHPI men and women experience relatively lower colon cancer incidence and mortality when compared with other racial groups in the United States. Colorectal cancer incidence among AANHPI is 30.0 persons per 100,000 compared with 38.6 persons per 100,000 among non-Hispanic white patients, and 45.7 persons per 100,000 among non-Hispanic Black patients. Similarly, mortality rates for AANHPI (9.5 persons per 100,000) are lower than that of non-Hispanic white patients (13.8 persons per 100,000) and non-Hispanic Black patients (19.0 persons per 100,000).8 However, much of this data on AANHPI is presented in the aggregate and may mask disparities among its numerous heterogeneous subpopulations: Japanese men, for instance, face a 23% higher incidence of colorectal cancer than non-Hispanic white men, whereas Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Filipino Americans tend to experience a lower incidence of colorectal cancer than non-Hispanic white patients.8,10 The vast inequities in income and educational attainment among certain AANHPI groups,11 as well as significant variation in sociocultural beliefs, lifestyles, health behaviors, and barriers to care,12,13 may manifest in specific presentation and treatment disparities by AANHPI subpopulation. These differences, however, are often neglected and lost in the average, thereby obscuring their significance and undermining efforts to further health equity.

Characterization and granular analysis of the colon cancer burden of disease may elucidate subpopulations of AANHPI patients who face the greatest care disparities and are in most need of improved health policies. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted systemic racism against Asian Americans and disproportionate mortality rates among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders,14,15 both of which have emphasized the need for greater research into the health inequities among AANHPI individuals. Through analysis of the National Cancer Database (NCDB), we sought to provide a comprehensive characterization of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals with colon cancer, as well as assess disparities in stage of presentation and time to surgery for these patients. We hypothesized that disaggregated data would reveal key disparities among AANHPI subpopulations.

Patients and Methods

Data Source and Patients

The NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society, with clinical oncology data sourced from hospital registries of more than 1500 accredited facilities.16 The data collected from the NCDB are estimated to include more than 70% of newly diagnosed colon cancer cases in the United States17 and allow for the disaggregation by Asian American subpopulation, given the large sample size.

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients diagnosed with stage 0, I, II, III, or IV colon cancer from 2004 to 2016 who identified as white, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Native Hawaiian, Korean, Vietnamese, Laotian, Hmong, Kampuchean, Thai, Asian Indian or Pakistani, and Pacific Islander. Although we recognize their incredible diversity and heterogeneity, patients who identified as Micronesian, Chamorran, Guamanian, Polynesian, Tahitian, Samoan, Tongan, Melanesian, Fiji Islander, New Guinean, and “Pacific Islander not otherwise specified (NOS)” were grouped together as a single cohort under Pacific Islander, given small sample sizes. Patients with incomplete staging data were excluded.

Clinical and Sociodemographic Covariates

The primary dependent variables of interest were stage of colon cancer upon presentation and the time-to-surgery threshold (≥ 60 days vs. 30–59 days vs. < 30 days between diagnosis and surgery)—distinctions that have been used previously.18,19 The independent variables studied here included race/ethnicity, age, sex, facility type, median household income for each patient’s ZIP code of residence (proxy for socioeconomic status), percentage of adults in the patient’s ZIP code who did not graduate from high school (proxy for educational attainment), Charlson–Deyo comorbidity coefficient score, insurance status, and year of diagnosis. Patient data corresponding to income and education made use of quartiles that were derived from the 2012 American Community Survey for each patient’s home ZIP code.

Statistical Analysis

Ordinal logistic regressions were employed to compare the effects of the above categorical and quantitative independent variables on ordinal dependent variables. These regression models defined adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of (1) patients presenting with advanced stage colon cancer, adjusting for all aforementioned independent variables, and 2) patients receiving surgery at ≥ 60 days vs. 30–59 days vs. < 30 days postdiagnosis (AOR > 1 indicates greater odds of delayed time to surgery), adjusting for stage of colon cancer and all aforementioned independent variables.20 Patients with stage IV colon cancer were excluded from the time-to-surgery model, given that their course of treatment is typically limited to radiation therapy and chemotherapy.21,22

Separate models defined AORs with 95% CIs for each primary dependent variable, initially with white patients as the referent group as they represent the largest race/ethnicity group in the NCDB. Subsequently, analyses were conducted in which white patients were excluded from the regression to allow for comparison amongst AANHPI patients with Chinese Americans as the referent, given their large sample size. Analyses were performed with Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was determined to be exempt by the institutional review board because of its use of deidentified data.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Of 694,876 patients with colon cancer included in the study, 43,949 (6.32%) had stage 0, 151,118 (21.75%) had stage I, 185,816 (26.74%) had stage II, 178,290 (25.66%) had stage III, and 135,703 (19.53%) had stage IV disease (Table 1). Median age was 71 [interquartile range (IQR) 60–80] years, and 16,925 patients (2.44%) had no insurance or were on Medicaid. White Americans comprised 97.55% (N = 677,818), and AANHPI patients comprised 2.45% (N = 17,058). Of the 17,058 AANHPI patients, Chinese Americans accounted for 24.33% (N = 4151), Japanese 15.57% (N = 2656), Filipino 15.18% (N = 2590), Native Hawaiian 3.42% (N = 584), Korean 11.02% (N = 1880), Vietnamese 10.52% (N = 1795), Laotian 1.10% (N = 187), Hmong 0.51% (N = 87), Kampuchean 1.15% (N = 197), Thai 1.00% (N = 170), Asian Indian or Pakistani 13.50% (N = 2302), and Pacific Islander 2.69% (N = 459). Disaggregated AANHPI demographic composition by region of origin is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

A comparison of baseline cohort characteristics between white and AANHPI patients is presented in Table 2. On average, white patients were older (white: 71 years vs. AANHPI: 67 years), presented with a higher stage of colon cancer (white: 45.1% at stage III/IV vs. AANHPI: 50.1% at stage III/IV), were less likely to be treated at academic/research programs (white: 24.9% vs. AANHPI: 37.0%), were more likely to reside in areas with the lowest quartile of median household income (white: 14.8% vs. AANHPI: 7.4%) and highest quartile of median education (white: 25.2% vs. AANHPI: 25.0%), had more comorbidities (Charlson–Deyo comorbidity coefficient > 0, white: 32.1% vs. AANHPI: 24.8%), and were less likely to be uninsured or on Medicaid (white: 5.8% vs. AANHPI: 16.4%).

Disparities in Stage at Presentation

Ordinal logistic regression modeling demonstrated that Japanese (AOR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.15, p < 0.05; 31.25% at stage III, 16.42% at stage IV), Filipino (AOR 1.17, 95% CI 1.09–1.25, p < 0.001; 30.66% at stage III, 21.93% at stage IV), Korean (AOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18, p < 0.05; 31.76% at stage III, 20.85% at stage IV), Laotian (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17–1.95, p < 0.01; 32.62% at stage III, 27.81% at stage IV), Kampuchean (AOR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04–1.70, p < 0.01; 32.99% at stage III, 25.38% at stage IV), Thai (AOR 1.60, 95% CI 1.22–2.10, p = 0.001; 40.00% at stage III, 27.65% at stage IV), and Pacific Islander (AOR 1.41, 95% CI 1.20–1.67, p < 0.001; 28.76% at stage III, 28.54% at stage IV) patients had greater odds of presenting at a higher stage of colon cancer compared with white patients (25.55% at stage III, 19.52% at stage IV) (Figs. 1A, 2A, and Supplementary Table 2). Conversely, Chinese Americans (AOR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90–1.00, p < 0.05; 29.99% at stage III, 18.07% at stage IV) were less likely to present at a higher stage of colon cancer than white patients. In subgroup analysis including only AANHPI patients, with Chinese patients as the referent group, Japanese (AOR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.22, p < 0.05), Filipino (AOR 1.25, 95% CI 1.14–1.36, p < 0.001), Korean (AOR 1.15, 95% CI 1.04–1.27, p < 0.01), Laotian (AOR 1.68, 95% CI 1.29–2.19, p < 0.001), Hmong (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.04–2.20, p < 0.05), Kampuchean (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17–1.94, p < 0.01), Thai (AOR 1.74, 95% CI 1.32–2.30, p < 0.001), and Pacific Islander (AOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.25–1.79, p < 0.001) patients were more likely to present at a higher stage of colon cancer (Supplementary Table 3). No significant differences were identified for Native Hawaiian, Vietnamese, and Asian Indian or Pakistani patients.

A Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) comparing the odds of presenting at a progressively higher stage based on AANHPI subgroup (referent—white). B Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) comparing the odds of experiencing treatment delays (≥ 60 days vs. 30–59 days vs. < 30 days postdiagnosis) based on AANHPI subgroup (referent—white)

Disparities in Time-to-Surgery Delay

Ordinal logistic regression modeling demonstrated that Chinese (AOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.17–1.38, p < 0.001; 32.22% at ≥ 60 days), Japanese (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.10–1.37, p < 0.001; 23.80% at ≥ 60 days), Filipino (AOR 1.36, 95% CI 1.22–1.52, p < 0.001; 31.27% at ≥ 60 days), Korean (AOR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02–1.32, p < 0.05; 30.14% at ≥ 60 days), and Vietnamese (AOR 1.55, 95% CI 1.36–1.77, p < 0.001; 33.53% at ≥ 60 days) patients were more likely to experience higher time-to-surgery periods than white patients (24.86% at ≥ 60 days) (Figs. 1B, 2B, and Supplementary Table 4). On subgroup analysis of only AANHPI patients, there was no statistically significant difference between the time-to-surgery threshold between the other ethnic subgroups and Chinese patients, although there was a trend suggesting that Native Hawaiian (AOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60–1.02, p = 0.071), Laotian (AOR 0.62, 95% CI 0.39–1.00, p = 0.052), and Asian Indian or Pakistani (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74–1.00, p = 0.053) patients were less likely to experience treatment delays than Chinese patients (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

In this national analysis of 694,876 patients, we comprehensively characterize AANHPI individuals diagnosed with colon cancer and evaluate disparities in stage at presentation and time to surgery. We found that, after adjusting for an array of sociodemographic covariates, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Laotian, Kampuchean, Thai, and Pacific Islander patients, who represented about 50% of the AANHPI cohort, were more likely to present at a higher stage of colon cancer compared with their white counterparts. These disparities were mirrored for Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese patients, who represented over 75% of the AANPHI cohort and were more likely to experience longer time-to-surgery delays than white patients, after similarly adjusting for sociodemographic covariates and colon cancer stage. Restricting both analyses to only AANHPI patients, key subgroup disparities were elucidated. Our findings emphasize that AANHPI patients with colon cancer may be more likely to present at a higher stage and to receive delayed treatment, even though, on average, incidence and mortality may be lower among AANHPI individuals relative to white or Black individuals.

To date, few studies have focused on colon cancer disparities among AANHPI individuals and, if so, have primarily considered the population in the aggregate, masking the incredible diversity and heterogeneity of the various subpopulations. Furthermore, there is little research exploring these patients’ clinical experiences and barriers in access to care that impact diagnosis and subsequent uptake of treatment. Indeed, much of the healthcare disparity literature on colon cancer focuses on white versus Black populations,23,24 and these studies are critical to improving population health outcomes for racial minorities. The paucity of focus on health inequities among AANHPI individuals has become all the more apparent as the COVID-19 pandemic fueled anti-Asian xenophobia and hate crimes and disproportionately high mortality rates among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders.14,15,25,26,27,28 Another NCDB analysis revealed similarly widespread disparities in risk group at presentation, as well as access to treatment or active surveillance, for AANHPI patients with localized prostate adenocarcinoma.20 However, our study is the first to examine clinical care disparities, including stage at presentation and time to surgery, by AANHPI subpopulation for patients with colon cancer. In characterizing AANHPI patients with colon cancer, our study also provides a foundation for future research to build on and discern causative factors underlying these disparities.

Many factors may contribute to our observation that certain AANHPI subgroups, ranging from 50 to 75% of the population, were more likely to present with late-stage disease and face delayed surgery. For one, low colon cancer case rates among AANHPI may drive disparities because of reduced awareness among patients and diagnostic unfamiliarity among clinicians. Indeed, with limited exposure to colon cancer, AANHPI individuals may be less likely to proactively mitigate risk or seek out timely care for colon cancer. Similarly, lack of clinician familiarity with colon cancer in AANHPI individuals can contribute to delayed delivery of preventive services, as well as misdiagnosis. Indeed, healthcare providers are less likely to recommend colon cancer screening to racial minorities,29 perhaps reflecting certain implicit bias in the differential diagnosis of AANHPI individuals.

Beyond low case rates, social disadvantage may be driving the disparities we found. While Asian Americans are generally studied as a homogeneous group with high rates of educational attainment and economic success, significant within-group differences and healthcare needs exist amongst Asian American subgroups—who have the greatest within-group disparities in socioeconomic status and educational attainment of all groups in the US, particularly affecting many Kampuchean, Hmong, Laotian, and Vietnamese individuals.30,31,32 Native Hawaiians similarly often experience lower income and educational attainment,33,34 paralleling the experiences of Pacific Islanders who identify as Native Chamorros, Māori, Kanak, and others.33 AANHPI groups also face high rates of disfluency and limited English proficiency,35 which likely impair access to screening and cancer care. Importantly, educational and socioeconomic disparities in general have been associated with reduced screening and treatment rates, as well as worse postoperative outcomes.36,37,38,39 This greater social disadvantage of AANHPI can be rooted to long histories of racism and discrimination in the USA, but manifests presently in the form of lower health literacy rates, and thus the reduced uptake of preventive care services and treatment. Indeed, multiple studies have found that greater health literacy regarding colon cancer can increase colonoscopy rates and health-seeking behavior more broadly, potentially reducing delays in care.40,41,42,43 Although our models adjusted for sociodemographic factors such as educational attainment, income, and insurance status, social disadvantage in the form of increased exposure to health risks and reduced access to healthy behaviors and care resources may help explain the disparities we found in stage-at-presentation and time-to-surgery delays, as well as provide avenues for policy action.

Our data suggest the need to further personalize screening and treatment regimens in manners that take into consideration race and ethnicity, especially at a granular level for AANHPI individuals. Tailored, culturally competent screening strategies, as have been pursued for Vietnamese,44 Filipino,45 Chinese,46 Pacific Islander,47 Native Hawaiian,48 and other AANHPI Americans, should be endorsed to help individuals mitigate risk and should be expanded to help combat treatment disparities as well. Some salient strategies from these studies included multilingual, tailored health education resources, media campaigns within diasporic outlets, care delivery in community contexts, and interactions with racially/ethnically concordant healthcare personnel. These approaches should be further refined and supported to combat stage-at-presentation and delay-to-surgery disparities. Another potential consideration may be developing new screening paradigms for ethnic subgroups at high risk of colon cancer. For instance, Japan and Korea have national gastric cancer screening programs because incidence is especially high, and Stanford’s Center for Asian Health Research and Education is working to implement a similar program for Asian Americans in the Bay Area.49 Finally, more granular race and ethnicity data are needed to better identify AANHPI disparities that might otherwise be masked and lost in the average. Addressing systemic barriers to colon cancer care and measuring progress toward eliminating health disparities necessitates disaggregated, granular data for AANHPI.

There are several limitations to this study that are important to note. First, our retrospective approach may suffer from selection bias and carries the risk of misclassification. Only patients who have access to Commission on Cancer-accredited facilities, which contribute data to the NCDB, are included, such that our findings may in fact underestimate the gravity of the disparities in access. The NCDB, more generally, is limited in the data that are available: there are no data available for patients’ preferred language, and there is high prevalence of missing data on patients’ overall survival.50 Furthermore, low sample sizes led us to aggregate Pacific Islanders in spite of the incredible cultural diversity of this group.51,52 With no information on patients who identify with multiple AANHPI identities, or on cultural preferences, our conclusions are further limited by certain lack of granularity and explanatory power. While the NCDB represents one of the largest available data sources on AANHPI, greater representation of minority racial/ethnic groups in data sources is necessary. Finally, we identified, but could not fully ascertain, the reasons for disparities in stage at presentation and time to surgery. Detailed prospective research will be needed to further investigate these disparities and clarify the mechanisms through which they act.

Conclusions

Our study uses a disaggregated approach to present a comprehensive understanding of colon cancer stage and treatment disparities among AANHPI patients. Indeed, we elucidated disparities in stage at presentation and time to surgery for Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, Laotian, Kampuchean, Thai, and Pacific Islander Americans relative to white patients. Our data emphasize the need for further investigation into various genetic and environmental risk factors, as well as levers of social disadvantage that affect AANHPI patients with colon cancer. Further research investigating and assessing causes of these disparities may improve population-wide outcomes by ensuring all individuals have access to preventive services and timely treatment following diagnosis. Consistent with recommendations from oncology providers and epidemiologists,28 understanding cultural, sociodemographic, and clinical factors associated with presentation and treatment disparities may promote improved and shared decision making.

Data availability

The data underlying this article were provided by the American College of Surgeons under license. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of the American College of Surgeons.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021.; 2021. Accessed July 14, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf

Jackson CS, Oman M, Patel AM, Vega KJ. Health disparities in colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7(Suppl 1):S32. https://doi.org/10.3978/J.ISSN.2078-6891.2015.039.

Obrochta CA, Murphy JD, Tsou MH, Thompson CA. Disentangling racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in treatment for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2021;30(8):1546–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1728.

Wiese D, Stroup AM, Maiti A, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in colon cancer survival: revisiting neighborhood poverty using residential histories. Epidemiology. 2020;31(5):728–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001216.

Pulte D, Jansen L, Brenner H. Disparities in colon cancer survival by insurance type: a population-based analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(5):538–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001068.

Kim SE, Paik HY, Yoon H, Lee JE, Kim N, Sung MK. Sex- and gender-specific disparities in colorectal cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(17):5167–75. https://doi.org/10.3748/WJG.V21.I17.5167.

Pilleron S, Charvat H, Araghi M, et al. Age disparities in stage-specific colon cancer survival across seven countries: an International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership SURVMARK-2 population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(7):1575–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/IJC.33326.

American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2020-2022. American Cancer Society, Atlanta; 2020.

Lee RJ, Madan RA, Kim J, Posadas EM, Yu EY. Disparities in cancer care and the Asian American population. Oncologist. 2021;26(6):453–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/ONCO.13748.

Gu M, Thapa S. Colorectal cancer in the United States and a review of its heterogeneity among Asian American subgroups. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(4):193–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/AJCO.13324.

Kochhar R, Cilluffo A. Income Inequality in the U.S. is rising most rapidly among Asians. Pew Res Cent.

López G, Ruiz N, Patten E. Key facts about Asian Americans. Pew Res. Cent. Published September 8, 2017. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/

Gordon NP, Lin TY, Rau J, Lo JC. Aggregation of Asian-American subgroups masks meaningful differences in health and health risks among Asian ethnicities: an electronic health record based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1551. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7683-3.

Racism in the USA. ensuring Asian American health equity. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00769-8.

Penaia CS, Morey BN, Thomas KB, et al. Disparities in native hawaiian and pacific islander COVID-19 mortality: a community-driven data response. Am J Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306370.

Participant User Files. National cancer database. Published 2016. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/puf

Mallin K, Browner A, Palis B, et al. Incident cases captured in the national cancer database compared with those in U.S. population based central cancer registries in 2012–2014. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(6):1604–12. https://doi.org/10.1245/S10434-019-07213-1.

Fligor SC, Wang S, Allar BG, et al. Gastrointestinal malignancies and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence-based triage to surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(10):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11605-020-04712-5.

Zhao H, Zhang N, Ho V, et al. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival for older patients with stage II or III colon cancer in Texas from 2001 to 2011. Cancer. 2018;124(4):679. https://doi.org/10.1002/CNCR.31094.

Jain B, Ng K, Santos PMG, et al. Prostate cancer disparities in risk group at presentation and access to treatment for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders: a study with disaggregated ethnic groups. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.21.00412.

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colon cancer, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16(4):359–69. https://doi.org/10.6004/JNCCN.2018.0021.

Gao X, Kahl AR, Goffredo P, et al. Treatment of stage IV colon cancer in the United States: a patterns-of-care analysis. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18(6):689–99. https://doi.org/10.6004/JNCCN.2020.7533.

Alty IG, Dee EC, Cusack JC, et al. Refusal of surgery for colon cancer: Sociodemographic disparities and survival implications among US patients with resectable disease. Am J Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.020.

Snyder RA, Hu CY, Zafar SN, Francescatti A, Chang GJ. Racial disparities in recurrence and overall survival in patients with locoregional colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):770–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/JNCI/DJAA182.

Wang D, Gee GC, Bahiru E, Yang EH, Hsu JJ. Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders in COVID-19: emerging disparities amid discrimination. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3685. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11606-020-06264-5.

Cabral S. Covid “hate crimes” against Asian Americans on rise. BBC News. Published 2021. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684

Santos PMG, Dee EC, Deville C. Confronting Anti-Asian racism and health disparities in the era of COVID-19. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(9):e212579–e212579. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAHEALTHFORUM.2021.2579.

Dee EC, Chen S, Garcia Santos PM, Wu SZ, Cheng I, Gomez SL. Anti-Asian American racism: a wake-up call for population-based cancer research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0445.

May FP, Almario CV, Ponce N, Spiegel BMR. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1388–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/AJG.2015.138.

Kim W, Keefe RH. Barriers to healthcare among Asian Americans. Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25(3):286–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371910903240704.

Ramakrishnan K, Ahmad FZ. Income and Poverty: Part of the “State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders” Series.; 2014. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/AAPI-IncomePoverty.pdf

Ramakrishnan K, Ahmad FZ. Education: Part of the “State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders” Series.; 2014. Accessed January 10, 2022. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/2012_release/

Taparra K, Miller RC, Deville C. Navigating Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander cancer disparities from a cultural and historical perspective. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.00831.

Doàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KLK, Irvin VL. Trends in clinical research including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432.

Ramakrishnan K, Ahmad FZ. Language Diversity and English Proficiency: Part of the “State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders” Series.; 2014. Accessed April 26, 2021. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/pums_data/

Dik VK, Aarts MJ, Van Grevenstein WMU, et al. Association between socioeconomic status, surgical treatment and mortality in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101(9):1173–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/BJS.9555.

Cavalli-Björkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(9):1398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJCA.2010.12.013.

van den Berg I, Buettner S, van den Braak RRJC, et al. Low socioeconomic status is associated with worse outcomes after curative surgery for colorectal cancer: results from a large, multicenter study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(11):2628–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11605-019-04435-2/TABLES/5.

Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Reed G, Field TS, Fletcher R. Socioeconomic and racial patterns of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees in 2000 to 2005. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(8):2170–5. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0104.

Sentell T, Braun KL, Davis J, Davis T. Colorectal cancer screening: low health literacy and limited English proficiency among Asians and Whites in California. J Health Commun. 2013;18(Suppl 1):242–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825669.

Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, Dietrich MS, Rothman RL. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1105.

Pancar N, Mercan Y. Association between health literacy and colorectal cancer screening behaviors in adults in Northwestern Turkey. Eur J Public Health. 2021;31(2):361–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURPUB/CKAA227.

Arnold CL, Rademaker AW, Morris JD, Ferguson LA, Wiltz G, Davis TC. Follow-up approaches to a health literacy intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening in rural community clinics: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3615–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/CNCR.32398.

Nguyen BH, McPhee SJ, Stewart SL, Doan HT. Effectiveness of a controlled trial to promote colorectal cancer screening in Vietnamese Americans. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):870. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.166231.

Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Danao LL, Antonio C, Garcia GM, Crespi CM. Results of a community-based randomized trial to increase colorectal cancer screening among Filipino Americans. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2228. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.176230.

Wang JHY, Ma GX, Liang W, et al. Physician intervention and Chinese Americans’ colorectal cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2018;42(1):13. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.42.1.2.

Sur R, Peters R, Leilani Beck L, et al. A Pacific Islander organization’s approach towards increasing community colorectal cancer knowledge and beliefs. Calif J Health Promot. 2013;11(2):12.

Braun KL, Fong M, Kaanoi ME, Kamaka ML, Gotay CC. Testing a culturally appropriate, theory-based intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening among native Hawaiians. Prev Med (Baltim). 2005;40(6):619. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YPMED.2004.09.005.

Moskal E. Stomach cancer hits Asian populations harder. Scope. Published December 16, 2022. https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2022/12/16/stomach-cancer-asians/. Accessed 16 Jan 2023

Yang DX, Khera R, Miccio JA, et al. Prevalence of missing data in the national cancer database and association with overall survival. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e211793–e211793. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2021.1793.

The White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.commerce.gov/bureaus-and-offices/os/whiaapi

Jolly M, Tcherkézoff S, Tryon D. (2009) Oceanic Encounters: Exchange, Desire, Violence. Anu Press, p. 344.

Acknowledgment

V.M. is employed by Northwest Permanente. B.A.M. receives funding from the Prostate Cancer Foundation and (PCF), the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the Department of Defense, and the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center outside the submitted work. P.L.N. reported receiving grants and personal fees from Bayer, Janssen, and Astellas, and personal fees from Boston Scientific, Dendreon, Ferring, COTA, Blue Earth Diagnostics, and Augmenix outside the submitted work. P.L.N. is also funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grand Number R01-CA240582). E.C.D. is funded in part through the Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748).

Funding

The funding was provided by National Cancer Institute (Grant Number P30 CA008748).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.J., S.S.B., and T.A.P. carried out formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft, visualization. N.V., M.B.L., B.A.M., V.M., and T.B.A. carried out the writing—review and editing, supervision, and validation. P.L.N., N.N.S., and E.C.D. carried out conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, and project administration.

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jain, B., Bajaj, S.S., Patel, T.A. et al. Colon Cancer Disparities in Stage at Presentation and Time to Surgery for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders: A Study with Disaggregated Ethnic Groups. Ann Surg Oncol 30, 5495–5505 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13339-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13339-0