Abstract

Background

High-intensity cancer surgery is increasingly common among older adults. However, these patients are at high-risk for unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) admissions after surgery. How these admissions impact older adults’ long-term outcomes is unknown.

Methods

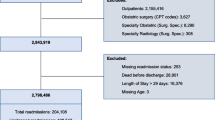

We performed a population-based, cohort study of older adults (age ≥ 70 years) who underwent high-intensity cancer surgery from 2007 to 2017. Analyses were performed to examine time alive and at home following surgery, defined as time from surgery to nursing home admission or death. Patients were followed for up to 5 years. Extended Cox proportional hazards models examined the independent association between unexpected ICU admission (ICU admissions excluding routine postoperative monitoring) and remaining alive and at home. Subgroup analysis stratified patients by duration of mechanical ventilation (MV).

Results

Of 47,367 identified older adults, 7372 (15.6%) had an unexpected ICU admission. Patients with an unexpected ICU admission had a significantly lower probability of being alive and at home at 5 years (26.2%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 25.1–27.2%) compared with those without an unexpected admission (56.8%; 95% CI 56.3–57.4%). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, unexpected ICU admission remained associated with less time alive and at home. The elevated risk of death or nursing home admission persisted for 5 years after surgery (years 2–5: hazard ratio [HR] 1.58, 95% CI 1.50–1.66). Duration of MV was inversely associated with time alive and at home.

Conclusions

Older adults with an unexpected ICU admission after high-intensity cancer surgery are at increased risk for death or admission to a nursing home for at least 5 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

24 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-11006-w

References

Gloeckler Ries LA, Reichman ME, Lewis DR, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Cancer survival and incidence from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Oncologist. 2003;8(6):541–52. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-541.

Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–65. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983.

DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Dale W, et al. Cancer statistics for adults aged 85 years and older, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):452–67. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21577.

Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):424–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53159.x.

Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Henderson WG, et al. Major cancer surgery in the elderly: results from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):311–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b6b04c.

Onwochei DN, Fabes J, Walker D, Kumar G, Moonesinghe SR. Critical care after major surgery: a systematic review of risk factors for unplanned admission. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(Suppl 1):e62–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14793.

Barnato AE, Albert SM, Angus DC, Lave JR, Degenholtz HB. Disability among elderly survivors of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(8):1037–42. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201002-0301OC.

Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, Herridge MS, Cuthbertson BH, Scales DC. Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness—a population-based study. Crit Care. 2016;20:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1248-y.

Wunsch H, Guerra C, Barnato AE, Angus DC, Li G, Linde-Zwirble WT. Three-year outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries who survive intensive care. JAMA. 2010;303(9):849–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.216.

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1293–304. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011802.

Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1553.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1301372.

Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303(8):763–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.167.

Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R6. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8848.

Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa012528.

Fried TR, Tinetti M, Agostini J, Iannone L, Towle V. Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(2):278–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.032.

Robinson TN. Function: an essential postoperative outcome for older adults. Ann Surg. 2018;268(6):918–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002866.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885.

Robles SC, Marrett LD, Clarke EA, Risch HA. An application of capture-recapture methods to the estimation of completeness of cancer registration. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(5):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(88)90052-2.

Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3.

Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge abstract database: a validation study. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006.

Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(4):325–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819.

Scales DC, Guan J, Martin CM, Redelmeier DA. Administrative data accurately identified intensive care unit admissions in Ontario. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(8):802–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.015.

Bayer A-H, Harper L. Fixing to stay: a national survey of housing and home modification issues. Washington, DC; 2000.

Hendin A, Tanuseputro P, McIsaac DI, et al. Frailty is associated with decreased time spent at home after critical illness: a population-based study. J Intensive Care Med. 2020:885066620939055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066620939055

Rectenwald JE, Huber TS, Martin TD, et al. Functional outcome after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(4):640–7. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2002.119238.

Dyer SM, Crotty M, Fairhall N, et al. A critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip fracture. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0332-0.

Jerath A, Austin PC, Wijeysundera DN. Days alive and out of hospital: validation of a patient-centered outcome for perioperative medicine. Anesthesiology. 2019;131(1):84–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002701.

Guttman MP, Tillmann BW, Nathens AB, et al. Alive and at home: five-year outcomes in older adults following emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90(2):287–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000003018.

Government_of_Ontario. Long-term care overview. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Available at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/about-long-term-care. Accessed 8 Feb 2021.

Hirdes JP, Poss JW, Curtin-Telegdi N. The method for assigning priority levels (MAPLe): a new decision-support system for allocating home care resources. BMC Med. 2008;6:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-6-9.

Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Manuel D, et al. Association between immigrant status and end-of-life care in Ontario, Canada. JAMA. 2017;318(15):1479–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.14418.

Wilkins R. Use of postal codes and addresses in the analysis of health data. Health Rep. 1993;5(2):157–77.

Kralj B. Measuring 'rurality' for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ontario Medical Review. 2000;October

Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, Roos N, Atkinson M. Performance of the ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care. 2001;39(1):86–99.

Ho MM, Camacho X, Gruneir A, Bronskill SE. Overview of Cohorts, In: Health System Use by Frail Ontario Seniors: An In-Depth Examination of Four Vulnerable Cohorts. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2011.

Sternberg SA, Bentur N, Abrams C, et al. Identifying frail older people using predictive modeling. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(10):e392–7.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471-4. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4

Nam RK, Cheung P, Herschorn S, et al. Incidence of complications other than urinary incontinence or erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):223–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70606-5.

Kagedan DJ, Abraham L, Goyert N, et al. Beyond the dollar: influence of sociodemographic marginalization on surgical resection, adjuvant therapy, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3175–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30148.

Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610910902859574.

Dekker FW, de Mutsert R, van Dijk PC, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. Survival analysis: time-dependent effects and time-varying risk factors. Kidney Int. 2008;74(8):994–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2008.328.

Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, Pieterse ME, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(7):121. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.02.12.

Angus DC. Admitting elderly patients to the intensive care unit—is it the right decision? JAMA. 2017;318(15):1443–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.14535.

Nguyen YL, Angus DC, Boumendil A, Guidet B. The challenge of admitting the very elderly to intensive care. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-1-29.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Boumendil A, Pateron D, et al. Selection of intensive care unit admission criteria for patients aged 80 years and over and compliance of emergency and intensive care unit physicians with the selected criteria: an observational, multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2919–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181b019f0.

Guidet B, De Lange DW, Christensen S, et al. Attitudes of physicians towards the care of critically ill elderly patients—a European survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62(2):207–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13021.

Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):523–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7889.

Schwarze ML, Bradley CT, Brasel KJ. Surgical “buy-in”: the contractual relationship between surgeons and patients that influences decisions regarding life-supporting therapy. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):843–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc466b.

Ioannidis JP. Exposure-wide epidemiology: revisiting Bradford Hill. Stat Med. 2016;35(11):1749–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6825.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the Sunnybrook AFP Innovation Fund and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (P.HSR.156). This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Members of the RESTORE-C group

Amy Hsu, PhD and Douglas Manuel, MD, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario; Frances Wright, MD, Dov Gandell, MD, and Ines Menjak, MD, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario; Lesley Gotlib-Conn, PhD, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, Ontario; Grace Paladino, patient and family advisor; Pietro Galuzzo, patient and family advisor.

Funding

This study was funded by the Sunnybrook AFP Innovation Fund and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (P.HSR.156).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

JH has received speaking honoraria from Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Canada, Novartis Oncology, and Advanced Accelerator Applications. NC receives salary support from Cancer Care Ontario as Lead for Patient-Reported Outcomes, and an honorarium from Astra-Zeneca.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Work performed at ICES, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The original online version of this article was revised: Wing C. Chan's family name was corrected.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tillmann, B.W., Hallet, J., Guttman, M.P. et al. A Population-Based Analysis of Long-Term Outcomes Among Older Adults Requiring Unexpected Intensive Care Unit Admission After Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 7014–7024 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10705-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10705-8