Abstract

Background

In the era of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many Complex General Surgical Oncology (CGSO) fellowship programs implemented virtual interviews (VI) during the 2020 interview season. At our institution, we had the unique opportunity to conduct an in-person interview (IPI) prior to the pandemic-related travel restrictions, and a VI after the restrictions were in place.

Objective

The goal of this study was to understand how the VI model compares with the traditional IPI approach.

Methods

Online surveys were distributed to both groups, collecting feedback on their interview experience. Responses were evaluated using a two-sample t test assuming equal variances.

Results

Twenty-three of 26 (88%) applicants completed the survey. Most applicants reported that the interview gave them a satisfactory understanding of the CGSO fellowship (100% IPI, 92% VI) and the majority in both groups felt that the interview experience allowed them to accurately represent themselves (92% and 82%, respectively). All participants in the IPI group felt they were able to get an adequate understanding of the culture of the program, while only 64% in the VI group agreed with that statement (p = 0.02). IPI applicants were more likely to agree that the interview experience was sufficient to allow them to make a ranking decision (92% vs. 54%; p = 0.04).

Conclusions

While the VI modality offers several advantages over the IPI, it still falls short in conveying some of the more subjective aspects of the programs, including program culture. Strategies to provide applicants with better insight into these areas during the VI will be important moving forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and ensuing travel restrictions to help curb the spread of the virus1 affected the interview seasons of over 20 surgical subspecialty fellowships, including Complex General Surgical Oncology (CGSO).2 CSGO is one of the most competitive surgical fellowship programs as defined by the applicant:position ratio. There was concern that the virtual interview (VI) format may not provide as much depth, both from the program and applicant perspectives, as the in-person interview (IPI) format, potentially having a negative impact on the applicants who participated in the VI experience.

Prior to the era of COVID-19, the VI was already being considered in medicine for several reasons. At the individual level, the traditional IPI model incurs substantial cost, stress, and time commitments that can negatively impact individuals’ current training program, and at the program level, there is the strain of cost, time, and resource utilization. The interview process for surgical residency and fellowship is very time-consuming and costly,3 and the introduction of videoconferencing to supplement or replace the traditional interview process has been evolving for several years, with primers on videoconferencing, to assist applicants, published both prior to4 and during the era of COVID-19.5 The VI format has been implemented in several fields of medicine with promising results. This format has been associated with positive feedback from applicants, improved efficiency, and decreased cost.6,7,8,9,10,11 However, there are also concerns surrounding VI related to the ability to understand the culture of a program and the city in which it is located, as well as experience interactions between faculty and fellows.12

We had a unique opportunity to compare the effectiveness of VI with the traditional IPI format using two groups of applicants from the same interview cycle. We offered 2 interview days for the CGSO fellowship at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill in 2020. The first occurred in March 2020, just prior to the widespread implementation of travel restrictions, and was completed using our standard IPI format. The second occurred in April 2020 and was attended virtually by all applicants due to the pandemic travel restrictions. Our goal was to explore how the VI experience compared with the IPI experience regarding the ability to convey a feel of the culture of the program, and to determine if sufficient information was communicated during the interview process for applicants to make an informed ranking decision. Our secondary aim was to learn how the VI experience could be improved upon for future implementation.

Methods

We developed a voluntary and anonymous survey (“Appendix”) that was distributed through a secure, web-based service (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA). The survey was distributed to all applicants who were interviewed for the CGSO Fellowship at UNC Chapel Hill during the 2020 interview cycle. There were two separate interview dates offered at our institution, the first on 4 March 2020 and the second on 20 April 2020. The first interview was a standard IPI and the second interview day was conducted virtually.

Prior to both the IPI and the VI, the applicants received identical information packets detailing the CGSO fellowship at UNC. During our IPI, we started with an optional social gathering the night prior to the interview with current fellows and applicants, in downtown Chapel Hill. The morning of the interview, all applicants meet for breakfast and our program director (DWO) gave an information session about the program. The applicants then proceeded to individual interviews (25–28 min) with each of our 12 surgical oncology faculty members. In between the individual interviews, the current fellows were available, in a separate room, to answer questions and discuss the program. For the VI format that we developed this year, there was no virtual social gathering preceding the interview day. On the morning of the interview, all applicants signed into the interview using the Zoom videoconference application (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA). As a group, they received the same informational session that was presented at the IPI by our program director. Our information technology (IT) specialist then moved each applicant to their assigned individual interview (20–22 min). In between each interview, our IT specialist brought all applicants and all faculty back into the shared room (3–5 min) to provide an opportunity for informal interaction with the entire applicant/fellow/faculty group together in one virtual shared room. The process was then repeated throughout the interview day. If an applicant did not have an interview during a given time period, the applicant was brought back to a virtual shared room with the current fellows. This provided time with the fellows alone, without faculty oversight or involvement, to remove any perceived barriers to asking questions about the fellowship program.

All applicants received the same survey with identical questions. The survey was open for a 4-week period between 23 April and 18 May 2020. The questions were designed to elucidate their perception of the interview experience and understand positive and negative aspects of the experience. Applicants were asked questions using a 3-point scale (1 = agree, 2 = neutral, 3 = disagree). The questions focused on different aspects of the interview day, including logistics and communication, how well the interview allowed them to understand the culture of the program, and if they learned enough to comfortably rank the program. There was also space for open response answers aimed at understanding more about particular negative or positive experiences related to their respective interview day. The survey did not collect any additional demographic data on race identity, ethnicity, sex, age, or geographic location. The reported demographic data were pooled from all applicants who were interviewed, including the three who did not respond to the survey.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel’s Data Analysis Package (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Differences in responses based on in-person versus virtual interview days were evaluated using a two-sample t test assuming equal variances. Demographic data were not collected regarding interview cohorts and thus was not used in these analyses. There was no difference in candidate selection (performance, strength of application) across the two cohorts. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Eighty-eight percent (23/26) of applicants responded to the survey, 12 of 14 (86%) from the IPI day and 11 of 12 (92%) from the VI day. There were no significant differences between the group of applicants who attending the IPI compared with those who attended the VI. Forty-six percent were male (50% IPI vs. 42% VI; p = 0.68). The average age of the applicants was 34 years in the IPI group and 35 years in the VI group (p = 0.28). Geographic location, number of publications, and average ABSITE scores were also similar between groups (Table 1). The majority felt that the interview day was a positive experience (87%, 20/23) and all applicants felt that the communication prior to and during the interview was satisfactory. As a group, 96% (22/23) agreed that the interview met their expectations and that the interview gave them a satisfactory understanding of the UNC CGSO fellowship, regardless of the interview format.

The majority in both groups agreed that they were able to accurately represent themselves to the program during the interview (92% vs. 82%). When asked if the interview experience helped them decide if our program was the right fit for them, there was a trend towards significance favoring the in-person group (92% vs. 64%; p = 0.11). There were significant differences between groups regarding their ability to discern an adequate understanding of the culture of the program, and their ability to make a ranking decision based on the interview day. All participants in the IPI group felt they were able to get an adequate picture of the culture of the program at UNC, while only 64% in the VI group agreed with that statement (p = 0.02). Ninety-two percent of the IPI group agreed with the statement that the interview experience was sufficient to allow them to make a ranking decision, compared with only 54% in the VI group (p = 0.04) (Fig. 1).

Our survey offered a free response section to allow the applicant to accentuate positive and/or negative aspects about our interview process. When asked about factors that were positive or done well during the interview experience, three candidates in the VI group specifically mentioned that the interview format allowed them to see interactions between faculty as well as between faculty and fellows. One candidate stated that our videoconference configuration with all faculty members together between sessions was the only VI they had experienced that allowed them to see faculty–faculty interactions. Other suggestions from the VI-day applicants included more dedicated time with the current fellows and more in-depth information about the program prior to the interview.

Discussion

This study highlights that while VI replaced the traditional IPI model for many surgical subspecialty fellowships this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic,2 at our institution we need to continue to improve the model to ensure that we provide a comparable interview experience for applicants to our program. This is especially important in light of the recent recommendations by the Coalition for Physician Accountability stating that, “All fellowship programs should commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants” for the upcoming 2020–2021 interview season.13 We found that although the VI modality gave applicants a satisfactory understanding of the UNC CGSO fellowship and allowed them to accurately represent themselves, virtual interviewees were significantly less likely to feel that the interview experience gave them an adequate picture of the culture of the program or enough information to make an informed ranking decision. This is of substantial consequence, as understanding the culture of a program could arguably be the most important part of the interview process for many applicants. We did find that several participants from the VI group enjoyed seeing the interactions between faculty and fellows, an important component of the culture at UNC, and that our particular virtual format with large group sessions between interviews was somewhat unique in facilitating exposure to these interactions.

Applicant interviews using videoconferencing technology has been explored as an alternative or replacement for the traditional IPI model for several years prior to this current global pandemic.4 Videoconferencing has been utilized during the application process for several different areas of medicine, including surgical fellowship programs.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,14 This interview format offers several benefits, including reduced stress and improved time efficiency related to travel, and coordination of time off for multiple interviews during a busy medical school or residency schedule, as well as substantial cost savings related to flights and travel accommodations, which is invaluable as student debt continues to increase.6,7,8,9,15 In a national survey of surgical residents, Watson et al. reported that over one-third attend 8–12 interviews and a majority spend over $4000 and miss 7 or more days of clinical training.15 Cost is an important consideration, not only for the applicants but also for the residency and fellowship programs. Gardner et al. reported that the average interview cost for general surgery residency programs was over $8000 in hard cost, such as food, supplies, and other fees that could otherwise be avoided using the VI format.3

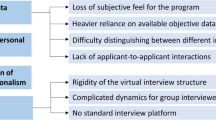

Despite the wide-ranging benefits of the videoconference format, there are several trepidations that limit its integration. Most of our applicants found the VI to be a positive experience and reported that it gave them a satisfactory understanding of the UNC CGSO fellowship. Additionally, they felt that it allowed them to accurately represent themselves. However, a significant concern for applicants in our study was the ability to understand the culture or feel of the program through the VI format, as well as the ability to get enough information to make a ranking decision. This is very similar to the findings in another highly competitive surgical subspecialty, pediatric surgery.10 Most pediatric surgery fellowship applicants felt they were able to accurately represent themselves via the virtual format, but both applicants and faculty reported that videoconference interviewing could not substitute for on-site interviews. Daram et al. also describe similar limitations of integrating videoconference into the gastroenterology fellowship selection process. While, overall, they felt that videoconferencing could be an effective and useful tool, they identify three major drawbacks of the process: inability to gain detailed knowledge about the city and the program institution, as well as an inability to effectively interact with fellows and faculty in the program.12 Collectively, including our study, it is clear that while videoconferencing shows promise as part of the interview process for fellowship programs, there are several areas that need improvement.

The responses from our VI applicants suggest that by creating a virtual group space to reconvene throughout the VI day, they were able to see interactions between both the faculty and the fellows. This is encouraging as we may be able to continue to improve the format as the video technology improves, to allow for even more interaction. To address the recurring theme of the inability to obtain detailed knowledge of the program institution and the city, it will be important to refine the access applicants have to such information. Here at UNC, similar to many other universities, there is a robust virtual tour online for potential undergraduates. We need to harness this expertise to develop an up-to-date online tour of the medical facilities, research opportunities, and surrounding environment. This could include improving the CGSO program website and the information that is sent out prior to the interview, as well as the addition of video content by faculty and current fellows related to the fellowship program.2 While each of our faculty has personal videos on their faculty profile website, they are not speaking specifically about the fellowship or the training culture at UNC.

There are several limitations to our study. This was a single-institution study with a limited sample size, which limits our power to detect significant differences between groups as well as the generalizability of our study. We believe the statistical significance seen in our comparison is real given the free text comments we received and the anecdotal responses we have heard from other CGSO programs. We fully acknowledge that this could be a type II error because of the small sample size, but feel this is unlikely. We would like to study match data from other CGSO sites that also had both IPI and VI interviews to understand if applicant match rates were affected by interview type and how many of the successfully matched fellows across the country matched at a site they visited personally, rather than virtually. We matched a candidate from our IPI day and are very interested to know if there is a pattern to the match of IPI versus VI. It will also be important to explore if there are any significant differences in applicant experience with the VI format based on applicant demographics such as age, geographic proximity to the interview site, marital status, and/or children. For instance, there may also be a geographic bias, with applicants already familiar with the geographic area feeling more comfortable ranking a program based on a VI alone because of previous knowledge of the area. There is also the possibility of a recall bias as the survey was distributed following the second interview, therefore those who participated in the second VI received the study 1 week after their interview, and those who participated in the first IPI received the survey 7 weeks following their interview. There is also the possibility that applicants may be biased toward more favorable responses in hopes of making a more favorable impression and increasing their chance of matching, since the survey was distributed prior to the submission of rank lists. The survey was anonymous and voluntary to help avoid this bias.

Conclusions

The possibility of offering a VI to candidates with the option of an IPI later if desired has been described.6 This will not be possible in the 2020–2021 interview season but perhaps can be explored in future interview seasons. However, this has the potential to create a disparity between those who have the time and can afford to travel and those who do not. We believe that VIs offer potential advantages over IPIs, including cost savings and efficiency, but we need to significantly improve the applicant’s ability to gain a feel of the culture of a program and, most importantly, make an informed ranking decision. We feel that most of the VI shortcomings that have been identified in this study can by addressed with purposeful, focused interventions and that this technology has the potential to become a valuable addition to the application process and potentially replace the IPI format. In accordance with the most recent recommendations from the Coalition for Physician Accountability, at least through the coming interview season the CGSO interviews will be in a videoconferencing interview format. We plan to incorporate what we have learned from this study to make improvements to our website, add video content from our faculty and fellows, and provide a dedicated virtual tour of the medical and research facilities as well as the surrounding Chapel Hill area in order to ensure a productive and successful interview season in this era of change.

References

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400.

Vining CC, Eng OS, Hogg ME, et al. Virtual surgical fellowship recruitment during COVID-19 and its implications for resident/fellow recruitment in the future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08623-2.

Gardner AK, Smink DS, Scott BG, Korndorffer JR Jr, Harrington D, Ritter EM. How much are we spending on resident selection? J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):e85–90.

Williams K, Kling JM, Labonte HR, Blair JE. Videoconference interviewing: tips for success. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):331–3.

Jones RE, Abdelfattah KR. Virtual interviews in the era of COVID-19: a primer for applicants. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):733–4.

Pasadhika S, Altenbernd T, Ober RR, Harvey EM, Miller JM. Residency interview video conferencing. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):426–e5.

Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503–5.

Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1380–4.

Melendez MM, Dobryansky M, Alizadeh K. Live online video interviews dramatically improve the plastic surgery residency application process. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):240e–1e.

Chandler NM, Litz CN, Chang HL, Danielson PD. Efficacy of videoconference interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):420–6.

Healy WL, Bedair H. Videoconference interviews for an adult reconstruction fellowship: lessons learned. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2017;99(21):e114.

Daram SR, Wu R, Tang SJ. Interview from anywhere: feasibility and utility of web-based videoconference interviews in the gastroenterology fellowship selection process. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(2):155–9.

National Residency Matching Program. Coalition for Physician Accountability Documents. 2020. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Recommendations-for-Fellowships-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2020.

Ballejos MP, Oglesbee S, Hettema J, Sapien R. An equivalence study of interview platform: does videoconference technology impact medical school acceptance rates of different groups? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(3):601–10.

Watson SL, Hollis RH, Oladeji L, Xu S, Porterfield JR, Ponce BA. The burden of the fellowship interview process on general surgery residents and programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(1):167–72.

Acknowledgment

None.

Funding

No sources of funding or material support were used in the preparation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Monica M. Grova, Sean J. Donohue, Michael O. Meyers, Hong Jin Kim, and David W. Ollila have no disclosures to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: UNC CGSO Interviews—Follow Up Survey

Appendix: UNC CGSO Interviews—Follow Up Survey

Thank you for your participation! All questions refer to your interview experience for the Complex General Surgical Oncology Fellowship at UNC Chapel Hill.

The survey contains 14 questions and should take approximately 5 minutes. Please answer all questions if possible. Your input is very valuable to us.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grova, M.M., Donohue, S.J., Meyers, M.O. et al. Direct Comparison of In-Person Versus Virtual Interviews for Complex General Surgical Oncology Fellowship in the COVID-19 Era. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 1908–1915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09398-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09398-2