Abstract

Background

Several states use certificate of need regulations (CON) to control the growth of acute-care services, but the possible association between these restrictions and the provision of cancer surgery has not been assessed. This study examines the association between acute-care CON, the availability of cancer surgery hospitals, and provision of six cancer operations.

Methods

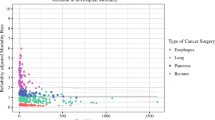

Medicare data were collected for beneficiaries treated with one of six cancer resections and an associated cancer diagnosis from 1989 to 2002. Hospital, procedure, and incidence rates for each cancer diagnosis were stratified by state and year. The number of hospitals performing each operation per cancer incident, the number of procedures performed per cancer incident, and hospital volume were compared between states with and without CON, and those that discontinued CON during the sample period were noted.

Results

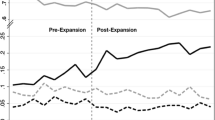

The number of hospitals per cancer incident was lower in CON states versus non-CON states for colectomy (P = .022), rectal resection (P = .026), and pulmonary lobectomy (P = .032). Hospital volume was significantly higher in CON states versus non-CON states for colectomy (P = .006) and pulmonary lobectomy (P = .043). There were no differences between states with and without CON in the number of procedures per cancer incident.

Conclusion

Although use of cancer procedures was similar in CON and non-CON states, those with acute-care CON had fewer facilities performing oncologic resections per cancer patient. Correspondingly, average hospital procedure volume tended to be higher in CON states. These differences may have important implications for patient outcomes and costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Melhado EM. Health planning in the United States and the decline of public-interest policymaking. Milbank Q 2006; 84:359–440

Conover CJ, Sloan FA. Does removing certificate-of-need regulations lead to a surge in health care spending? J Health Politics Policy Law 1998; 23:455–81

DiSesa VJM, O’Brien SMP, Welke KFM, et al. Contemporary impact of state certificate-of-need regulations for cardiac surgery: an analysis using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ National Cardiac Surgery Database. Circulation 2006; 114:2122–9

Spitz B, Abramson J. When health policy is the problem: a report from the field. J Health Politics Policy Law 2005; 30:327–65

Mayo JW, McFarland DA. Regulation, market structure, and hospital costs. South Econ J 1989; 55:559–69

American Health Planning Association. National Directory of Health Planning, Policy and Regulatory Agencies, 13th edition. Falls Church, VA: American Health Planning Association, 2002

Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Hannan EL, Cormley CJ, et al. Mortality in Medicare beneficiaries following coronary artery bypass graft surgery in states with and without certificate of need regulation. JAMA 2002; 288:1859–66

Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Certificate of need regulations and use of coronary revascularization after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2006; 295:2141–7

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. International Classification of Diseases. 9th revision (ICD-9). 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd9.htm#RTF. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, et al. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA 1998; 280:1747–51

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SRG, Tosteson ANA, et al. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 1999; 125:250–6

Harmon JW, Tang DG, Gordon TA, et al. Hospital volume can serve as a surrogate for surgeon volume for achieving excellent outcomes in colorectal resection. Ann Surg 1999; 230:404–13

Romano PS, Mark DH. Patient and hospital characteristics related to in-hospital mortality after lung cancer resection. Chest 1992; 101:1332–7

Patti MG, Corvera CU, Glasgow RE, et al. A hospital’s annual rate of esophagectomy influences the operative mortality rate. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2:186–92

Finlayson EVA, Birkmeyer JD. Operative mortality with elective surgery in older adults. Eff Clin Pract 2001; 4:172–7

Ho V, Heslin MJ, Yun H, et al. Trends in hospital and surgeon volume and operative mortality for cancer surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 13:851–8

North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR). CINA + online. Available at: http://www.cancer-rates.info/naaccr/

Cancer in North America, 1989–1993. Incidence. 1. 1997. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Available at: http://www.naaccr.org/index.asp?Col_SectionKey=11&Col_ContentID=51. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Cancer in North America, 1990–1994. Incidence. 1. 1998. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Available at: http://www.naaccr.org/index.asp?Col_SectionKey=11&Col_ContentID=51. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Cancer in North America, 1991–1995. Incidence. 1. 1999. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Available at: http://www.naaccr.org/index.asp?Col_SectionKey=11&Col_ContentID=51. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Cancer in North America, 1992–1996. Incidence. 1. 2000. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Available at: http://www.naaccr.org/index.asp?Col_SectionKey=11&Col_ContentID=51. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Cancer in North America, 1993–1997. Chen VW, Howe HL, Wu XC, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], III-1-III-50. 2000. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2006

Cancer in North America, 1994–1998. Howe HL, Chen VW, Hotes JL, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], III-1-III-49. 2001. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2006

Cancer in North America, 1995–1999. Wu XC, Hotes JL, Fulton JP, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], III-1-III-49. 2002. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2006

Cancer in North America, 1996–2000. Hotes JL, Wu XC, McLaughlin CC, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], III-1-III-51. 2003. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2006

Cancer in North America, 1997–2001. McLaughlin CC, Cormier M, Wu XC, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], IV-1-IV-51. 2004. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries

Cancer in North America, 1998–2002. Ellison JH, Wu XC, Howe HL, et al. (eds). Incidence. [1], III-1-III-52. 2005. Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2006

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Public-Use Data (1973–2003). 2006. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed: April 15, 2008

US Census Bureau. State population estimates. 2007. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/stats

Bureau of Economic Analysis. Regional Economic Accounts. Annual state personal income, 2006. Available at: http://www.bea.gov/bea/regional/spi/default.cfm?satable=summary. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State county file, 2006. Available at: http://www3.cms.hhs.gov/HealthPlanRepFileData/02_SC.asp. Accessed: April 15, 2008

HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2002. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed: April 15, 2008

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson SR, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1128–37

Hodgson DC, Zhang W, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Relation of hospital volume to colostomy rates and survival for patients with rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95:708–16

Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, et al. Influence of hospital procedure volume on outcomes following surgery for colon cancer. JAMA 2000; 284:3028–35

Acknowledgment

This research was supported in part by grant RSGHP-03−076-01-PBP from the American Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Short, M.N., Aloia, T.A. & Ho, V. Certificate of Need Regulations and the Availability and Use of Cancer Resections. Ann Surg Oncol 15, 1837–1845 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-008-9914-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-008-9914-1