Abstract

Background

We examine the epidemiology, natural history, and prognostic factors that affect the duration of survival for islet cell carcinoma by using population-based registries.

Methods

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database (1973–2003 release, April 2006) was used to identify cases of islet cell carcinoma by histology codes and tumor site.

Results

A total of 1310 (619 women and 691 men) cases with a median age of 59 years were identified. The annual age-adjusted incidence in the periods covered by SEER 9 (1973–1991), SEER 13 (1992–1999), and SEER 17 (2000–2003) were .16, .14, and .12 per 100,000, respectively. The estimated 28-year limited duration prevalence on January 1, 2003, in the United States was 2705 cases. Classified by SEER stage, localized, regional, and distant stages corresponded to 14%, 23%, and 54% of cases. The median survival was 38 months. By stage, median survival for patients with localized, regional, and distant disease were 124 (95% CI, 80–168) months, 70 (95% CI, 54–86) months, and 23 (95% CI, 20–26) months, respectively. By multivariate Cox proportional modeling, stage (P < .001), primary tumor location (P = .04), and age at diagnosis (P < .001) were found to be significant predictors of survival.

Conclusions

Islet cell carcinomas account for approximately 1.3% of cancers arising in the pancreas. Most patients have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Despite the disease’s reputation of being indolent, survival of patients with advanced disease remains only 2 years. Development of novel therapeutic approaches is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Islet cell carcinomas are low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas. Also known as pancreatic endocrine tumors or pancreatic carcinoid, they account for the minority of pancreatic neoplasms and are generally more indolent than pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Islet cell carcinomas, which arise from islets of Langerhans, can produce insulin, glucagon, gastrin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, causing the characteristic syndromes of insulinoma, glucagonoma, gastrinoma, and VIPoma. Pancreatic polypeptide is also frequently produced, yet it is not associated with a distinct clinically evident syndrome.

Although the molecular biology of sporadic islet cell carcinoma is less well understood than other more common solid tumors, they can arise in connection with several hereditary cancer syndromes. The best known of these, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder characterized by tumors of the parathyroids, pituitary, and pancreas.1 Less commonly, neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors of the duodenum (gastrinomas), lung, thymus, and stomach have also been described.2

Tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis are two other hereditary cancer syndromes associated with the development of neuroendocrine tumors. TSC1/2 complex inhibits mTOR and is normally expressed in neuroendocrine cells.3 Patients with a defect in the TSC2 gene have tuberous sclerosis and are known to develop islet cell carcinoma.4 Neurofibromatosis is associated with the development of carcinoid tumors of the ampulla of Vater, duodenum, and mediastinum.5,6 The gene responsible for neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) regulates the activity of TSC2. The loss of NF1 in neurofibromatosis leads to constitutive mTOR activation.7 Finally, islet cell carcinomas also occur in approximately 12% of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL).8 The vHL gene is located on chromosome 3p26–p25; inactivation of the vHL gene is thought to stimulate angiogenesis by promoting increased HIF-1α activity.

Little is known about the epidemiology and natural history of islet cell carcinoma. Although several case series have been reported, there have been few population-based studies. This is in part due the uncommonness of this disease as well as the complexity of its classification. Although pancreatic carcinoid based on ICD-O-3 histology classification (8240–8245) has been partially described in studies of carcinoid from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program,9 these have been incomplete analyses because most islet cell carcinomas were coded differently in the ICD-O-3 system (8150–8155). Survival of patients with islet cell tumors was also described in a recent report on malignant digestive endocrine tumors that was based on data from England and Wales.10 In this population-based study, we have undertaken a comprehensive analysis of patients with islet cell carcinoma identified through the SEER Program database in the United States.

METHODS

The SEER Program was created as a result of the National Cancer Act of 1971. The goal of the SEER Program is to collect data useful in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. In this study, we used the SEER data based on the November 2005 submission. For incidence and prevalence analyses, registry data was linked to total U.S. population data from 1969 to 2003.11

Since 1973, the SEER Program has expanded several times to improve representative sampling of minority groups as well as to increase the total sampling of cases to allow for greater precision. The original SEER 9 registries included Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco–Oakland, Seattle–Puget Sound, and Utah. In 1992, four additional registries were added to form the SEER 13 registries, which included the SEER 9 registries, plus Los Angeles, San Jose–Monterey, rural Georgia, and the Alaska Native Tumor Registry. More recently, in 2000, data from greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Jersey were added to the SEER 13 Program to form the SEER 17 registries. SEER 9, 13, and 17 registries cover approximately 9.5%, 13.8%, and 26.2% of the total U.S. population, respectively. The data set we use here contains information about a total of 4,539,680 tumors from 4,123,001 patients diagnosed from 1973 to 2003.

Islet cell carcinomas were identified by search for ICO-O-3 histology codes 8150–8155, 8240–8245, and pancreatic primary site (duodenal gastrinomas were excluded). The included histology codes correspond to the following clinical/histologic diagnoses: islet cell carcinoma, insulinoma, glucagonoma, gastrinoma, mixed islet cell/exocrine carcinoma, VIPoma, carcinoid, enterochromaffin cell carcinoid, and adenocarcinoid. The SEER registries include neuroendocrine neoplasms that are considered invasive and malignant (behavior code of 2 or 3 in the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 2nd edition [ICD-O-2]). Cases designated as poorly differentiated or anaplastic were excluded. A total of 1310 cases of islet cell carcinoma were included in this study. Cases identified at the time of autopsy or by death certificate only were excluded (36 cases) from survival analyses.

Although a tumor, node, metastasis system classification system has recently been proposed,12 during the period of time that we studied, there was no accepted staging system for islet cell carcinoma. Here, we use the SEER staging system. Tumors in the SEER registries were classified as localized, regional, or distant. In this system, a localized neoplasm was defined as an invasive malignant neoplasm confined entirely to the organ of origin. A regional neoplasm was defined as a neoplasm that has (1) extended beyond the limits of the organ of origin directly into surrounding organs or tissue; (2) involves regional lymph nodes; or (3) fulfills both of the above. A distant neoplasm was defined as a neoplasm that has spread to parts of the body remote from the primary tumor.

The comparisons between patients, tumor characteristics and disease extension were based on the χ2 test. One-way analysis of variance was used for the comparison of continuous variables between groups. Survival duration was measured by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log rank test. The statistical independence between prognostic variables was evaluated by multivariate analysis by the Cox proportional hazard model.

SEER*Stat 6.2.4 (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute) was used for incidence and limited-duration prevalence analyses.13 All other statistical calculations were performed by SPSS 12.0 (Apache Software Foundation 2000). Survival durations calculated by SPSS were also verified by parallel analyses by SEER*Stat. Comparative differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was <.05.

RESULTS

Frequency and Incidence

Between 1973 and 2003, a total of 101,192 pancreatic neoplasms in 101,173 patients were identified in the SEER 17 registries. Among these, 101,046 neoplasms were classified as malignant and occurred in 101,029 patients. When we restricted the search to codes of neuroendocrine histology, a total of 1385 neoplasms in 1385 patients were identified. We removed 75 patients who were classified as having tumors of poorly differentiated or anaplastic grade. Thus, a total of 1310 patients had pancreatic islet cell carcinomas in the SEER registries. This consisted of 1.3% of all patients with pancreatic cancers.

By using linked population files, we calculated the incidence of islet cell carcinoma as a rate per 100,000 per year, age-adjusted to year 2000 U.S. standard population. Because the SEER 9, 13, and 17 registries were linked to different population data sets, we computed the age-adjusted incidence rates in three time periods. The age-adjusted incidence in the SEER 9 registries between 1973 and 1991 was .16 per 100,000. For the SEER 13 registries, from 1992 to 1999, an age-adjusted incidence of .14 per 100,000 was observed. Finally, for the period covered by the SEER 17 registries, from 2000 to 2003, the age-adjusted incidence rate was .12 per 100,000. This suggests that on the basis of the current U.S. population estimate of 302 million, approximately 362 cases of malignant islet cell carcinoma will be diagnosed each year. The number of small benign islet cell tumors may be higher. Detailed incidence data by time period, sex, and race are included in Table 1.

Limited Duration Prevalence

Among the population sampled by the SEER 9 registries, 28-year limited duration prevalence for islet cell carcinoma on January 1, 2003, was estimated by the counting method to be 227 (95% CI, 199–259). These data were then projected to the general U.S. population. Data were matched by sex, race, and age to the U.S. standard population. The estimated 28-year limited duration prevalence of islet cell carcinomas on January 1, 2003, in the United States was 2705 cases. In comparison, the 28-year limited duration prevalence for all pancreatic neoplasms regardless of histology was 27,201.14 Thus, although islet cell carcinoma represented 1.3% of pancreatic cancer by incidence, it represented 9.9% of cases by the 28-year limited duration prevalence analyses.

Patient Characteristics

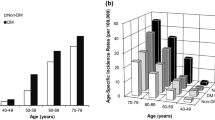

Of the 1310 patients with islet cell carcinoma identified in the SEER database, there were 619 women and 691 men. The majority (1095 cases) were white. African American and other racial groups accounted for 134 and 78 cases, respectively. Details of patient characteristics are included in Table 2. The other racial groups included American Indian/Alaskan Natives, and Asian/Pacific Islanders. In three cases, the race was unknown. We plotted the number of cases by age group at diagnosis in Fig. 1; the peak age distribution was 65 to 69 years. However, the median age at diagnosis was 59 years.

We next examined the effect of race and sex on age at diagnosis. The median age in years at diagnosis for white, African American, and other racial groups was 60 (mean 58, SD 14.9), 55 (mean 54.5, SD 16.5) and 56 (mean 57, SD 16.5), respectively (P = .02, Fig. 2). However, there was no difference in median age at diagnosis based on sex.

Tumor Location and Hormone Production

The location of the primary tumors within the pancreas was described in 868 cases. In 442 cases, the detailed location data is not known. This is partially because the current coding system allows tumor location to be coded as islet of Langerhans, which gives no information about the location of the tumor within the pancreas. In 379 cases, the primary tumor was located in the head of the pancreas; body, tail, and overlapping groups accounted for 103, 278, and 108 cases, respectively.

By ICD-O-3 histology codes, 1117 cases (Table 2) were coded as islet cell or carcinoid (ICD-O-3 = 8150, 8240, 8241). Because these designations can include either serotonin-producing or nonfunctional tumors, it is not possible to determine the secretory status in these cases. Among the known functional tumors, gastrinoma was the most common with 73 cases (22 cases of duodenal gastrinoma not included); insulinoma, glucagonoma, and VIPoma accounted for 49, 26, and 16 cases, respectively. Finally, in 26 cases, the tumors were considered to have mixed endocrine/exocrine histology (ICD-O-3 = 8154, 8243–8245).

Next, we compared the location of the primary tumors within the pancreas by histological classification. We found significant differences in the pattern of primary tumor localization (P = .029); nonfunctional or serotonin-producing tumors (coded as islet cell and carcinoid tumors) were more likely to be located in the head (44%) than in the body (12%) or tail (31%) or overlapping (14%). Among the functional neoplasms, most insulinomas (57%), glucagonomas (53%), and VIPomas (64%) were located in the tail of the pancreas. Gastrinomas were much more likely to be located in the head of the pancreas (63%).

Tumor Stage

Of the 1310 cases, 125 (10%) were not staged (Table 2). For the remaining 1185 cases, 179 (14%) were localized; 295 (23%) were classified as regional; and 711 (54%) were classified as distant. When we compared stage by ICD-O-3 histology, we found that most carcinomas were metastatic at the time of diagnosis, including islet cell carcinomas (61%), insulinomas (61%), glucagonomas (56%), and gastrinomas (60%). A smaller percentage of VIPomas (47%) were metastatic (P < .001). This may be the result of the presence of massive diarrhea in VIPoma patients, which may bring them to medical attention earlier. The higher rate of metastases among insulinoma patients observed in this study is likely because most small insulinoma are considered benign and not reported to SEER. Next, we compared stage by tumor location and found that tumors located at the head of the pancreas trended toward a lower rate of distant disease (48% head vs. 57% body, 58% tail, and 60% overlapping) and a higher rate of regional disease (34% head vs. 27% body, 23% tail, 27% overlapping). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .063).

Survival

For survival analyses, we excluded 36 cases that were identified at autopsy or on the basis of death certificates only. The median overall survival for all 1274 remaining cases was 38 months (95% CI, 34–43). When compared by the log rank test, SEER stage predicted patient outcome (P < .001). The median survival for patients with localized, regional, and distant islet cell carcinoma was 124 months, 70 months, and 23 months, respectively (Fig. 3). One-year, 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year survival rates are listed in Table 3. The median survival for those cases that were not staged was 50 (95% CI, 34–66) months. Relative risk was calculated by Cox proportional modeling. Compared to the group with localized disease, patients with regional and distant disease had 1.56- and 3.50-fold of increased risk of death during the period (1973–2005) included in this study.

We then examined potential prognostic factors for survival duration that were based on data available from the SEER database. For these analyses, we stratified patients by stage. Patients with missing stage data were excluded from the analyses. When compared against the group designated as islet cell or carcinoid by ICD-O-3 histology codes, patients with gastrinoma (P = .001) and VIPoma (P = .044) had longer survival durations after adjusting for the effect of stage (Table 4), while the group with mixed histology experienced worse survival. The difference was not statistically significant, which is likely because of the small number of cases in this category.

The location of the primary tumor may have a marked effect on the time of presentation (head tumors may obstruct the bile duct and cause visible jaundice) and resectability, as well as on surgical morbidity and mortality. Therefore, we next examined the prognostic role of the location of the primary tumor within the pancreas (Table 4). In our analyses, tumors located at the head of the pancreas were less likely to be associated with distant metastasis. The rates of distant metastasis for primary tumors located in the head, body, tail, and overlapping locations were 48%, 57%, 58%, and 60%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant (P = .063). However, once adjusted for stage, primary tumor location in the pancreatic head was associated with a worse prognosis than the pancreatic body (P = .037). Similarly, tumors in the pancreatic head tended to be associated with worse survival compared with those in the pancreatic tail (P = .056); however, the difference was not statistically significant. Patients with primary tumors that were classified as overlapping had the worst prognosis (P = .041). In some cases, an overlapping lesion may indicate a larger primary tumor that covered a larger portion of the pancreas.

Age is found to be a predictor of outcome in a variety of malignancies. We examined the effect of age at diagnosis on overall survival stratified by stage (Table 4, Fig. 4). In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, we separated the patients into two groups on the basis of median age. We observed decreasing survival with increasing age (P < .001). Similarly, we also examined the effect of age as a continuous variable in Cox proportional hazard modeling and found increasing age to be a predictor of poor outcome (P < .001).

Age and survival. For the <59 age group, the median survival durations for localized, regional, and distant disease were 282 (95% CI, 204–360) months, 114 (95% CI, 83–145) months, and 35 (28–42) months. For the 60+ age group, the median survival durations for localized, regional, and distant disease were 46 (95% CI, 20–72) months, 38 (95% CI, 24–52) months, and 13 (95% CI, 10–16) months (P < .001).

Next, we examined the survival duration of patients with islet cell carcinoma by year of diagnosis. There has been an improvement in survival over time. Whether analyzed as a continuous variable by Cox proportional hazard modeling or divided into discrete time durations, the observed difference was statistically significant (P = .001). Sex and race did not significantly affect survival. The details of these analyses are included in Table 4.

Finally, we performed multivariate survival analyses by Cox proportional hazard modeling. SEER stage, primary tumor localization, ICD-O-3 histology groups, and age at diagnosis were entered into the model. In multivariate analysis, the ICD-O-3 histology group was not a statistically significant predictor of outcome. All other variables retained statistical significance; the most important predictor of outcome was stage. Compared to patients with localized disease, patients with regional (HR = 1.44) and distant (HR = 3.40) disease had decreased survival duration. Location of the primary tumor within the pancreas (P = .032) and age at diagnosis (P < .001) also remained significant predictors of outcome (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In order for us to make advances in the diagnosis and management of patients with islet cell carcinoma, we must improve our understanding of the epidemiology, natural history, and prognostic factors for this relatively rare disease. Because of the rarity of neuroendocrine carcinoma and the lack of a staging system, much of the information previously published has been based on case series and anecdotal experiences. In this study, we take advantage of the vast amount of data collected by the SEER Program to examine the largest series of islet cell carcinomas reported to date. To our knowledge, this study represents the only population-based study of islet cell carcinoma in published literature.

Prevalence is defined as the number people alive on a certain date in a population that ever had a diagnosis of the disease. In this study, the counting method15 was used to estimate prevalence from incidence and follow-up data obtained from the SEER 9 registries. Complete prevalence can be established by this method by using registries of very long duration. The SEER 9 registries have the longest follow-up duration and contain data suitable for prevalence analyses for the past 28 years. Given the longer survival duration often experienced by patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma, we report only limited duration prevalence data which may somewhat underestimate the complete prevalence. By incidence, islet cell carcinomas account for only 1.3% of all pancreatic cancers. However, because of the better outcome generally experienced by patients with islet cell carcinoma, they represent almost 10% of pancreatic cancers in prevalence analyses.

We acknowledge that analyses from the SEER registries underestimate the total number of patients with islet cell tumors. All cases from the SEER database were denoted to be malignant. Thus, it is likely that small, benign-appearing tumors were not included in the SEER registries (for example, insulinomas and small nonfunctioning tumors). Although histologic evidence of invasion of basement membrane defines malignant behavior for most epithelial malignancies, the definition of malignant behavior for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms is more complex. In the absence of malignant behavior such as direct invasion of adjacent organs, metastases to regional lymph nodes or distant sites, it may be difficult to classify an islet cell tumor as benign or malignant. Pancreatic endocrine tumors are classified as benign, uncertain malignant potential, and malignant on the basis of size, the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion, and the number of mitoses and Ki-67–positive cells by immunohistochemistry. However, there is a considerable overlap among these histopathologic features in benign and malignant neuroendocrine tumors and there is even heterogeneity within different areas of the same tumor. Many small islet cell tumors may have been considered benign or of unclear malignant potential and were excluded from the SEER registries. However, size is likely a function of when a tumor is diagnosed; left untreated, it is likely that most islet cell tumors will eventually grow locally into adjacent structures or soft tissues, and/or spread to distant organs. Therefore, outside of small insulinomas, all islet cell neoplasms should be considered potentially malignant. Thus, although the SEER registry data provide important information about malignant islet cell tumors, the extent to which it underestimates the frequency of smaller islet cell neoplasms is unknown. In our experience, even small islet cell tumors without clear evidence of invasion or metastasis at the time of initial surgical resection may recur and spread years later.

We found a wide distribution of age at diagnosis, with a median of 59 years. Separated by race, white patients were older at the time of diagnosis. When we compared stage by histologic type, we found that VIPomas were less likely to be metastatic at the time of diagnosis. Several findings may have contributed to this observation. One possible explanation is that VIPomas are generally associated with profound watery diarrhea, which may cause patients to seek medical attention earlier than if they had nonfunctional tumors. Second, as previously mentioned, small insulinomas and gastrinomas may have been considered benign (in the absence of invasion of adjacent organs, lymph node metastases, or distant metastases) and therefore not captured for analysis thereby enriching the population of study patients with metastatic functioning tumor.

In an earlier publication that was based on data from the SEER Program, Modlin et al.9 described the five-year overall survival of patients with carcinoid tumors to be 59.5% to 67.2%. The survival of patients with islet cell carcinoma seems less favorable. In the present study, we observed a median overall survival of 38 months. This is identical to the median survival observed in a large retrospective series of 163 cases from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.16 The survival duration of patients with distant metastases was also similar (23 months in current study vs. 25 months in the M. D. Anderson series). We did, however, observe improvements in the outcome of patients with islet cell carcinoma over time. These improvements were observed among all SEER stage groups (data not shown), and are likely due in part to improvements in supportive care.

By multivariate survival analysis, we found that stage of disease, primary tumor location, and age at diagnosis were important predictors of outcome. The difference in survival by primary tumor location can be attributed to several possible factors. In this study, patients with tumors classified as having overlapping location had the worst outcome. This is likely because of the larger tumor size in this group. Tumor located at the head of pancreas may be diagnosed earlier because of hyperbilirubinemia resulting from biliary obstruction. This is suggested by our finding of a trend (nonsignificant) for a lower rate of metastastic disease at the time of diagnosis on the basis of tumor location in the pancreatic head. However, adjusted for stage, patients with a tumor located in the pancreatic head were more likely to have a worse outcome than patients with tumors located in the body or the tail of the pancreas. One possible explanation is that tumors arising in the pancreatic head are of greater malignant potential. For example, most insulinomas (57%), glucagonomas (53%), and VIPomas (64%) were located in the tail of the pancreas. Such functioning tumors were also associated with improved survival compared with nonfunctioning tumors. In addition, the fact that tumors in the pancreatic head are more likely to cause biliary obstruction (with a risk for cholangitis), invade the duodenum (resulting in hemorrhage or obstruction), or involve the peripancreatic mesenteric vasculature (resulting in pain, mesenteric foreshortening, and malabsorption) may contribute to local tumor morbidity which may influence survival duration. There is also likely to be a general tendency on the part of physicians to avoid surgical resection of the pancreatic head (pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple procedure) when faced with a large tumor or low volume metastatic disease. This is not the case with tumors in the body or tail of the pancreas that can be surgically excised with a distal pancreatectomy. However, it is the pancreatic head tumor that carries the greatest risk for tumor associated morbidity such as hemorrhage and biliary or gastric outlet obstruction.16 To what degree patients with pancreatic head tumors suffer morbidity and mortality from local disease progression rather than distant metastases cannot be determined from this data set.

Finally, increasing age at diagnosis was a predictor of poor outcome in our study. The differences in survival were seen across all SEER stage groupings. Certainly, pancreatic resection carries considerable operative risks and the medical comorbidities that are associated with advancing age may have precluded some patients from resection while increasing the risk to those taken to surgery. For patients with advanced disease, systemic chemotherapy often includes drugs that are considered toxic.17,18 For example, doxorubicin is recognized to be cardiotoxic, and streptozocin may cause worsening of diabetes. Thus, heart disease and diabetes which are more common among older patients may have limited the use of these drugs.

At present, surgery is the only curative treatment for islet cell carcinoma. Surgery should be recommended for most patients in whom cross-sectional imaging suggests that complete resection is possible.19 Although islet cell carcinoma has a better prognosis than adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, the disease remains incurable once multifocal unresectable metastatic disease exists. Although survival beyond 10 years has been described in the literature for some patients with metastatic disease, the survival duration for most with advanced disease is far shorter. Although streptozocin-based chemotherapy can induce objective response in 32% to 39% of patients,17,20 second-line treatment options are limited. Newer approaches such as peptide receptor radiotherapy, systemic agents targeting vascular endothelial growth factor, and mTOR are under development.

Optimal management of patients with islet cell carcinoma requires an understanding of the disease process and a multimodal approach. A better understanding of the molecular biology of this disease may lead to improved clinical models for predicting outcome and developing novel treatment strategies for this relatively rare but complex disease. Until then, an understanding of the natural history of the disease as provided herein is necessary to allow physicians and patients to accurately assess the risks and potential benefits of treatment alternatives that are based on the extent of disease and the age and performance status of the patient.

References

Lamberts S, Uitterlinden P, Verschoor L, van Dongen K, del Pozo E. Long term treatment of acromegaly with the somatosatin analogue SMS201-995. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1576–80

Debelenko LV, Brambilla E, Agarwal SK, et al. Identification of MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung. Hum Mol Genet 1997;6:2285–90

Plank TL, Logginidou H, Klein-Szanto A, Henske EP. The expression of hamartin, the product of the TSC1 gene, in normal human tissues and in TSC1- and TSC2-linked angiomyolipomas. Mod Pathol 1999;12:539–45

Verhoef S, van Diemen-Steenvoorde R, Akkersdijk WL, et al. Malignant pancreatic tumour within the spectrum of tuberous sclerosis complex in childhood. Eur J Pediatr 1999;158:284–7

Tan CC, Hall RI, Semeraro D, Irons RP, Freeman JG. Ampullary somatostatinoma associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis presenting as obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg Oncol 1996;22:298–301

Yoshida A, Hatanaka S, Ohi Y, Umekita Y, Yoshida H. von Recklinghausen’s disease associated with somatostatin-rich duodenal carcinoid (somatostatinoma), medullary thyroid carcinoma and diffuse adrenal medullary hyperplasia. Acta Pathol Jpn 1991;41:847–56

Johannessen CM, Reczek EE, James MF, Brems H, Legius E, Cichowski K. The NF1 tumor suppressor critically regulates TSC2 and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:8573–8

Hammel PR, Vilgrain V, Terris B, et al. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d’Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1087–95

Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003;97:934–59

Lepage C, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Survival from malignant digestive endocrine tumors in England and wales: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007;132:899–904

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: SEER 17 Regs Nov 2005 sub (1973–2003), ed. released April 2006. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistic Branch, 2006. Available at: Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed August 14, 2007

Rindi G, Kloppel G, Alhman H, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch 2006;449:395–401

Surveillance Research Program NCI. SEER*Stat software, version 6.2.4, 2006. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. Accessed August 14, 2007

SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2006

Byrne J, Kessler LG, Devesa SS. The prevalence of cancer among adults in the United States: 1987. Cancer 1992;69:2154–9

Solorzano CC, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Nonfunctioning islet cell carcinoma of the pancreas: survival results in a contemporary series of 163 patients. Surgery 2001;130:1078–85

Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4762–71

Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, Hahn RG, Klaassen D. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1992;326:519–23

Kouvaraki MA, Solorzano CC, Shapiro SE, et al. Surgical treatment of non-functioning pancreatic islet cell tumors. J Surg Oncol 2005;89:170–85

Eriksson B, Skogseid B, Lundqvist G, Wide L, Wilander E, Oberg K. Medical treatment and long-term survival in a prospective study of 84 patients with endocrine pancreatic tumors. Cancer 1990;65:1883–90

Acknowledgments

Supported by gifts from Raymond Sackler, the J. Stuart Foundation, and the Carcinoid Cancer Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, J.C., Eisner, M.P., Leary, C. et al. Population-Based Study of Islet Cell Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 14, 3492–3500 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9566-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9566-6