Abstract

We developed a novel process, “controlled crystallization during freeze-drying” to produce drug nanocrystals of poorly water-soluble drugs. This process involves freeze-drying at a relatively high temperature of a drug and a matrix material from a mixture of tertiary butyl alcohol and water, resulting in drug nanocrystals incorporated in a matrix. The aim of this study was to elucidate the mechanisms that determine the size of the drug crystals. Fenofibrate was used as a model lipophilic drug. To monitor the crystallization during freeze-drying, a Raman probe was placed just above the sample in the freeze-dryer. These in-line Raman spectroscopy measurements clearly revealed when the different components crystallized during freeze-drying. The solvents crystallized only during the freezing step, while the solutes only crystallized after the temperature was increased, but before drying started. Although the solutes crystallized only after the freezing step, both the freezing rate and the shelf temperature were critical parameters that determined the final crystal size. At a higher freezing rate, smaller interstitial spaces containing the freeze-concentrated fraction were formed, resulting in smaller drug crystals (based on dissolution data). On the other hand, when the solutes crystallized at a lower shelf temperature, the degree of supersaturation is higher, resulting in a higher nucleation rate and consequently more and therefore smaller crystals. In conclusion, for the model drug fenofibrate, a high freezing rate and a relatively low crystallization temperature resulted in the smallest crystals and therefore the highest dissolution rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Many newly developed drugs are categorized as class II drugs according to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (1). These drugs have a low solubility in water, but once dissolved, they are easily absorbed over the gastro-intestinal membrane (2,3). For many of these drugs, the dissolution rate is the rate-limiting step for absorption. Therefore, the bioavailability can be improved by increasing the dissolution rate (4). One strategy for increasing the dissolution rate is the application of drug nanocrystals (5–8). The dissolution rate of nanocrystals is increased by their increased surface area (Noyes–Whitney equation) (9), the decreased thickness of the diffusion boundary layer (10), and the increased saturation concentration around the small particles (Kelvin’s law) (11).

Current methods to prepare drug nanocrystals can be divided into top-down and bottom-up methods. Most currently used top-down methods are high-pressure homogenization (12) and wet-ball milling (13). Disadvantages of these methods include the use of surfactants, the difficulty of achieving a uniform size distribution, low yields, and possible contamination from grinding media (14–16). For currently used bottom-up methods, disadvantages include the use of toxic solvents and the difficulty of adequately controlling the particle size (16,17).

To overcome these disadvantages, we developed a novel bottom-up process to produce drug nanocrystals: controlled crystallization during freeze-drying (CCDF) (18). Briefly, this method consisted of the following steps. Firstly, two solutions are prepared: one is a solution of the poorly water-soluble drug in tertiary butyl alcohol (TBA) and the other is a solution of a matrix material in water. These solutions are mixed, frozen, and then freeze-dried. Freeze-drying is performed at a relatively high temperature to allow both the drug and the matrix to crystallize. By using this process, nanocrystalline dispersions with improved dissolution behavior were obtained.

When we developed this process, we found that the size of the nanocrystals was affected by the process conditions, such as the freezing rate. However, it was not clear during which stage of the process the solutes crystallized and how the freezing rate caused its effect on the crystal size. Since the mixture is thermodynamically unstable, the drug and the matrix could crystallize (1) during freezing, (2) after freezing at a temperature above the temperature of the maximally freeze-concentrated fraction (T g′), or (3) during drying. Knowledge on when and how crystallization occurs can help to elucidate the mechanisms through which parameters such as freezing rate affect the final size of the crystals. Crystallization processes can be monitored with Raman spectroscopy. The effects of the process conditions on the drug particle size could be elucidated if the crystallization of both the solvents and the solutes could be monitored during the freeze-drying process.

The aim of the study was to elucidate the mechanisms that determine the size of the drug crystals formed during freeze-drying. Thereto, in-line Raman spectroscopy was used as process analytical tool. Since Raman spectroscopy is a fast, non-invasive technique, it offers the opportunity to monitor physical changes of the formulation during freeze-drying. One of the advantages of Raman spectroscopy is that Raman spectra show sharp peaks by which individual components generally do not overlap each other. This makes it relatively easy to determine which component crystallizes at which stage during the process (19).

In this study, a Raman probe was placed immediately above the sample in the freeze-drier (as described by De Beer et al. (20)). By using this in-line method, the crystallization of the four components (a model drug, matrix, TBA, and water) during the process could be monitored. The different stages during the CCDF-process (freezing, increase in temperature, and drying) were separated from each other and prolonged to ensure that the complete phase changes during each stage were measured. In addition, two process conditions, the freezing rate and the temperature of the freeze-dryer shelf, were varied. Monitoring the crystallization process yields insight into the moment and length of the crystallization of the different components, while varying the process conditions reveals which factors influence the model drug crystal size and therefore the dissolution rate. Fenofibrate and mannitol were used as the model drug and the matrix material, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Fenofibrate and TBA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie B.V. Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands. Mannitol was purchased from VWR international (Fontenay sous Bois, France).

Methods

Preparation of the Crystalline Dispersions

Crystallized dispersions were prepared similar to the method described previously (18). Briefly, the drug, fenofibrate, was dissolved in TBA (25 mg/ml) and the matrix material, mannitol, in water (31 mg/ml). The solutions were heated to approximately 60°C and 2.4 ml of the aqueous solution was mixed with 1.6 ml of the TBA solution. After mixing, the vials were frozen. Two freezing rates were used: immediately freezing the vials on a pre-cooled (−50°C) freeze-dryer shelf (cooling rate of the sample approximately 2.5°C/min); and freezing at 1°C/min by placing the vial on the shelf at 20°C and cooling the shelf to −50°C at a rate of 1°C/min (cooling rate of the sample approximately 0.8°C/min). In both cases, the temperature of −50°C was maintained for 2 h. The temperature of the shelf was then increased to either −25°C or −15°C in 30 min and this temperature was maintained for another 7 h. Next, sublimation of the solvents was initiated by decreasing the pressure to 0.8–1.0 mbar in 20 min and the samples were dried for 30 h (see Table I). The temperature of the shelf was then gradually (2 h) raised to room temperature. Finally, the freeze-dryer (Amsco-Finn Aqua GT4 freeze-dryer) was emptied and the samples, having a drug load of 35% w/w, were stored in a vacuum desiccator over silica gel for at least 1 day before further processing.

In-Line Raman Spectroscopy

A non-contact probe coupled to a RamanRxn1 spectrometer (Kaiser Optical Systems, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) via a glass fiber optic cable, was placed immediately above a vial inside the freeze-dryer. The spectrometer was equipped with an air-cooled CCD detector (back-illuminated deep depletion design). The laser wavelength was the 785-nm line from a 785 Invictus NIR diode laser. Spectra were collected every minute during freeze-drying and the exposure time was 30 s. All spectra were recorded at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using a laser power of 400 mW. The HoloREACT reaction analysis and profiling software package, the Matlab Software package (version 6.5), and the Grams/AI-PLSplusIQ software package (version 7.02) were used for data-collection, -transfer, and -analysis. Spectra were preprocessed by baseline correction (Pearson’s method).

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

The degree of crystallinity (defined as the ratio between the heat of fusion of the drug or carrier in the solid dispersion and the heat of fusion of the drug or carrier as received multiplied by the fraction drug or carrier in the mixture) of fenofibrate and mannitol in the crystallized dispersions was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Hermetically closed aluminum pans were filled with 2–8 mg of the sample and heated at 2°C/min, from −50 to 200°C in the scanning calorimeter (Q2000, TA Instruments, Ghent, Belgium).

X-ray Powder Diffraction

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) was used to determine the crystallinity and identify the polymorphic forms of both solutes. Therefore a CuKα radiation with a wavelength of 1.5405 Å at 40 kV and 40 mA from an X'Pert PRO MPD diffractometer (PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) was used. The sample powders were placed on a zero-background silicon holder (diameter, 32 mm; thickness, 2 mm) and scanned from 4–60° 2θ with a step size of 0.008° and a time per step of 35 s.

Tabletting

The obtained powders were compressed to 9-mm tablets of 100 mg on a ESH compaction apparatus (Hydro Mooi, Appingedam, The Netherlands). The compaction rate was 5 kN/s to a maximum compaction load of 5 kN. The tablets were stored in a vacuum desiccator over silica gel at room temperature for at least 1 day before further processing.

Dissolution

The dissolution rate of fenofibrate from these tablets was tested in a USP dissolution apparatus II, Rowa Techniek. Dissolution was performed in 1 L of a 0.5% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate solution at 37°C; the paddle speed was 100 rpm. The concentration of fenofibrate was measured spectrophotometrically (UV–VIS spectrophotometer UV-1601, Shimadzu) at a wavelength of 290 nm.

RESULTS

Physicochemical Characterization of the Dispersions

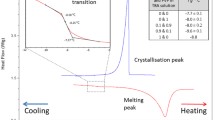

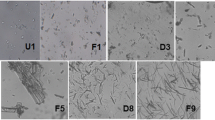

The physical properties of the obtained freeze-dried product were determined by both DSC and XRPD. The DSC thermograms of all four dispersions showed melting peaks corresponding to crystalline fenofibrate and crystalline mannitol. Mannitol exists as three anhydrous polymorphs whose melting points differ only slightly (166.5, 166, and 155°C for the α-, β-, and δ-polymorphs, respectively (21)). Therefore, DSC is not the most suitable method to identify which polymorph has been formed. The XRPD patterns showed that all samples contained only the δ-polymorph (Fig. 1). Although the pure mannitol as received did not consist of δ-mannitol, DSC can be used to determine the degree of crystallinity of mannitol since the melting enthalpies of α-, β-, and δ-mannitol are also similar (21). Fenofibrate and mannitol in all four dispersions were highly crystalline and had a similar degree of crystallinity (96–102% for fenofibrate and 92–95% for mannitol; Table II).

In-Line Raman Spectroscopy

Each crystalline component had a characteristic peak that did not overlap with characteristic peaks of any of the other components (Fig. 2). The characteristic peak used for fenofibrate was at 1580–1610 cm−1, for mannitol at 865–895 cm−1, for TBA at 725–763 cm−1, and for water at 208–226 cm−1 (22–24). Since these peaks can be clearly distinguished from each other, it is possible to use in-line Raman spectroscopy to monitor the crystallization of the individual components. To determine when crystallization of fenofibrate, δ-mannitol, and water started and ended, the peak intensity of each individual characteristic peak was determined. An increase in peak intensity indicates the start of crystallization. The peak intensity of the TBA peak cannot be used for the determination of the start and end of the TBA crystallization, since liquid TBA already shows a peak with a high intensity. Therefore, the width of the TBA peak was used to determine the crystallization of TBA. A narrowing of the peak indicates the start of the crystallization of TBA (25). Furthermore, it should be mentioned that Raman spectroscopy only allows to measure the surface of the sample.

The intensity of the water peak increased and the width of the TBA peak decreased during the freezing stage of process 1 (Fig. 3), corresponding to the crystallization of the solvents. The intensity of the fenofibrate peak decreased slightly due to the decrease in temperature and the peak of crystalline mannitol was not detected during this stage of the CCDF-process. Thus, only the solvents and not the solutes crystallized during the freezing stage. After approximately 80 min, the intensity of the solvent peaks did not change anymore, indicating that almost all solvent had crystallized. At this point during the CCDF-process, the system consisted of crystalline water (ice), crystalline TBA, and a vitrified freeze-concentrated solution of fenofibrate and mannitol in a mixture of water and TBA.

The intensities of fenofibrate (1,580–1,610 cm−1), mannitol (865–895 cm−1), and water (208–226 cm−1) peaks and the peak width of TBA (725–763 cm−1) during the first 1,000 min of process 1. During this process the freeze-drier shelf was cooled during the first 70 min from 20°C to −50°C, then the temperature was kept constant at −50°C for 120 min, then the temperature of the freeze-drier shelf was increased to −25°C in 30 min and kept constant for 420 min. Finally, the pressure was decreased to 0.8–1.0 mBar to dry the samples

After the temperature was increased to −25°C, the intensity of the peaks corresponding to both fenofibrate and mannitol increased. Indicating that the solutes crystallized at this stage. Since the intensities did not change any further after approximately 460 and 480 min for fenofibrate and mannitol, respectively (Table III), which was well before the vacuum was applied (after 640 min), these data show that fenofibrate and mannitol crystallized completely before the drying step started. After 650 min the width of the TBA peak increased and the intensity of the water peak decreased, indicating that sublimation started immediately after the pressure was decreased. Due to the sublimation of the solvents, the concentration of the solutes, and therefore the intensities of the solute peaks, increased. After 1,144 and 980 min the peaks of TBA and water, respectively, disappeared. Since only the surface of the sample can be measured by Raman spectroscopy, this indicates that the top of the sample was dried in approximately 8.5 h. To end with a completely dry crystalline dispersion, the total drying time used was 30 h.

The solutes and solvents of the other three processes crystallized at the same stages of the freeze-drying process as found for process 1 (Table III; note that step 2 of processes 3 and 4 start 70 min earlier than step 2 of process 1 and 2, due to the different freezing rate). The solvent crystallized upon cooling, while crystallization of the solutes was not observed at this stage. The solutes crystallized after the temperature had been increased to −25°C (processes 1 and 3) or −15°C (processes 2 and 4). Even if the mixture was cooled at a rate of at least 1°C/min, the solutes did not crystallize during freezing, but only after the temperature was increased. Since the intensity of the solute peaks reached a constant value before the vacuum was applied, the solutes indeed crystallized only during the time between freezing and drying.

Dissolution

As expected from earlier studies (18,26), the dissolution rate of samples that were made by rapid freezing (vials placed on a pre-cooled freeze-dryer shelf) was higher than the dissolution rate of samples that were frozen more slowly (at 1°C/min; see Fig. 4). Furthermore, a relatively low shelf temperature during the crystallization stage (−25°C) resulted in faster dissolution than a relatively high shelf temperature (−15°C). Between the samples that were crystallized at a relatively low temperature, the effect of the freezing rate on the dissolution behavior is negligible, indicating that crystallization at a lower temperature could diminish the effect of the freezing rate. Since all samples had a similar degree of crystallinity and consisted of the same polymorphic forms, differences in dissolution rate can be attributed to differences in crystal size (18,26). Thus, both the rate of freezing and the temperature at which crystallization occurs influence the final particle size. Based on the dissolution data, we conclude that a higher freezing rate and a lower temperature at which the solutes crystallized, resulted in smaller drug crystals.

Dissolution profiles of tablets composed of a physical mixture ( ) and controlled crystallized dispersions of 35% w/w fenofibrate in mannitol. Controlled crystallized dispersions were prepared by slow freezing (closed symbols) or fast freezing (open symbols) and a low (−25°C) crystallization temperature (circles) or a high (−15°C) crystallization temperature (triangles). Process 1 corresponds to (●), process 2 corresponds to (▲), process 3 corresponds to (○), and process 4 corresponds to (△) (n = 3–6; mean ± standard deviation)

) and controlled crystallized dispersions of 35% w/w fenofibrate in mannitol. Controlled crystallized dispersions were prepared by slow freezing (closed symbols) or fast freezing (open symbols) and a low (−25°C) crystallization temperature (circles) or a high (−15°C) crystallization temperature (triangles). Process 1 corresponds to (●), process 2 corresponds to (▲), process 3 corresponds to (○), and process 4 corresponds to (△) (n = 3–6; mean ± standard deviation)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we clearly elucidated the mechanism of crystallization during the CCDF-process. The in-line Raman spectroscopy measurements showed that the solvents and the solutes crystallized at different steps during the CCDF-process. During the freezing step, the solvents crystallize. Due to the crystallization of the solvents, the remaining solution becomes more concentrated. Since the remaining solution (containing fenofibrate, mannitol, TBA, and water) is thermodynamically unstable, the solutes can start to crystallize as well. However, if the freezing occurs rapidly, and if the system is cooled to a temperature well below the T g′, the mobility is strongly reduced and a rigid glass is formed. Due to the strongly reduced mobility neither the solvents nor the solutes can crystallize in the freeze-concentrated fraction. The in-line Raman data show that the solutes did not crystallize at the freezing stage of the CCDF-process. Thus, the freezing rate (even at 1°C/min) is apparently fast enough to prevent crystallization of the solutes during freezing and the reached temperature of −50°C is well below the T g′.

After step 2, when the temperature was increased to either −25°C or −15°C, the solutes crystallized and the crystallization was finished before the next step, drying, was started. The T g′ of the solutes could not be properly measured in this complex system by DSC (data not shown), but since the solutes crystallized at these temperatures, the temperature of the system was apparently above the T g′. At temperatures below the T g′, the freeze-concentrated fraction is glassy and the solutes cannot crystallize.

Although the solutes crystallized solely during the step after the freezing step, not only the crystallization temperature, but also the freezing rate determined the particle size of the powder. Therefore, we conclude that two phenomena play a role in the formation and growth of the crystals during CCDF.

The first process variable that determines the final crystal size was the freezing rate. A higher freezing rate resulted in smaller crystals. This effect was already shown in an earlier study, in which we also speculated about different mechanisms that could determine the drug crystal size (18). Since we have shown in this study that both the drug and the matrix crystallized after freezing, we conclude that the size of the solvent crystals determines the final solute crystal size. A higher freezing rate results in smaller solvent crystals (27) and consequently smaller interstitial spaces, containing the freeze-concentrated fraction, between the solvent crystals. Since the solutes crystallized in the freeze-concentrated fraction, the size of the interstitial spaces limits the final size of the solute crystals. Thus, a high freezing rate results in smaller solvent crystals and therefore smaller interstitial spaces and consequently smaller solute crystals.

The second process variable that determines the crystal size is the shelf temperature. We found that a lower shelf temperature during crystallization (−25°C vs. −15°C) resulted in smaller crystals. At a lower shelf temperature, the degree of supersaturation is higher, resulting in a higher nucleation rate (28). Since the formation of new nuclei and crystal growth are two competing processes (29), a higher nucleation rate results in more nuclei and consequently in smaller crystals. Thus, although the size of the interstitial spaces (controlled by the freezing rate) determines the maximum particle size, the crystal size is also determined by the balance between the formation of new nuclei and crystal growth (controlled by the shelf temperature).

CONCLUSION

In this study, we revealed during which stages of the CCDF-process the solvents as well as the solutes crystallized. Based on this, we identified the critical steps for crystal formation for the model drug fenofibrate during freeze-drying. CCDF consists of three successive steps: freezing, increasing the temperature, and drying. The in-line Raman measurements showed that the first two steps, the freezing step and the crystallization step are critical steps that determine the final size of the fenofibrate crystals. When the mixture was frozen more rapidly, the interstitial spaces between the solvent crystals are smaller and because the size of the solute crystals is limited by the size of the interstitial spaces, smaller fenofibrate crystals are formed. When the solutes crystallize at a lower shelf temperature, the degree of supersaturation in the freeze-concentrated fraction is higher. A higher degree of supersaturation (as caused by lower crystallization temperatures) results in a higher nucleation rate and consequently more and therefore smaller fenofibrate crystals are formed. The combination of a high freezing rate and a relative low crystallization temperature results in the smallest fenofibrate crystals and consequently a higher dissolution rate. Furthermore, these results show that the fenofibrate crystal size can be controlled by choosing the appropriate freezing rate and shelf temperature. Further studies are necessary to prove whether the critical steps as defined in this study and the mechanism of crystal formation are generally applicable to other lipophilic drugs.

References

Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26.

Lobenberg R, Amidon GL. Modern bioavailability, bioequivalence and biopharmaceutics classification system. New scientific approaches to international regulatory standards. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:3–12.

Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12:413–20.

Curatolo W. Physical chemical properties of oral drug candidates in the discovery and exploratory development settings. Pharm Sci Technol Today. 1998;1:387–93.

Jinno J, Kamada N, Miyake M, Yamada K, Mukai T, Odomi M, et al. Effect of particle size reduction on dissolution and oral absorption of a poorly water-soluble drug, cilostazol, in beagle dogs. J Control Release. 2006;111:56–64.

Hu J, Johnston KP, Williams 3rd RO. Nanoparticle engineering processes for enhancing the dissolution rates of poorly water soluble drugs. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2004;30:233–45.

Möschwitzer J, Müller RH. New method for the effective production of ultrafine drug nanocrystals. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:3145–53.

Blagden N, Matas MD, Gavan PT, York P. Crystal engineering of active pharmaceutical ingredients to improve solubility and dissolution rates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;57:617–30.

Noyes AA, Whitney WR. The rate of solution of solid substances in their own solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 1897;19:930–4.

Bisrat M, Nyström C. Physicochemical aspects of drug release. VIII. The relation between particle size and surface specific dissolution rate in agitated suspensions. Int J Pharm. 1988;47:223–31.

Hou D, Xie C, Huang K, Zhu C. The production and characteristics of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). Biomaterials. 2003;24:1781–5.

Müller RH, Peters K. Nanosuspensions for the formulation of poorly soluble drugs: I. Preparation by a size-reduction technique. Int J Pharm. 1998;160:229–37.

Merisko-Liversidge E, Liversidge GG, Cooper ER. Nanosizing: a formulation approach for poorly-water-soluble compounds. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2003;18:113–20.

Keck CM, Muller RH. Drug nanocrystals of poorly soluble drugs produced by high pressure homogenisation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;62:3–16.

Sarkari M, Brown J, Chen X, Swinnea S, Williams RO, Johnston KP. Enhanced drug dissolution using evaporative precipitation into aqueous solution. Int J Pharm. 2002;243:17–31.

Shekunov BY, Chattopadhyay P, Seitzinger J, Huff R. Nanoparticles of poorly water-soluble drugs prepared by supercritical fluid extraction of emulsions. Pharm Res. 2006;23:196–204.

Kipp JE. The role of solid nanoparticle technology in the parenteral delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. Int J Pharm. 2004;284:109–22.

de Waard H, Hinrichs WLJ, Frijlink HW. A novel bottom-up process to produce drug nanocrystals: controlled crystallization during freeze drying. J Control Release. 2008;128:179–83.

De Beer TRM, Baeyens WRG, Heyden YV, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Verpoort F. Influence of particle size on the quantitative determination of salicylic acid in a pharmaceutical ointment using FT-Raman spectroscopy. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2007;30:229–35.

De Beer TRM, Alleso M, Goethals F, Coppens A, Vander Heyden Y, Lopez De Diego H, et al. Implementation of a process analytical technology system in a freeze-drying process using raman spectroscopy for in-line process monitoring. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7992–8003.

Burger A, Henck JO, Hetz S, Rollinger JM, Weissnicht AA, Stottner H. Energy/temperature diagram and compression behavior of the polymorphs of d-mannitol. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89:457–68.

D'Arrigo G, Maisano G, Mallamace F, Migliardo P, Wanderlingh F. Raman scattering and structure of normal and supercooled water. J Chem Phys. 1981;75:4264–70.

Taylor LS, York P, Williams AC, Mehta V. Characterization of frozen glucose solutions. Pharm Dev Technol. 1997;2:395–402.

Romero-Torres S, Wikström H, Grant ER, Taylor LS. Monitoring of mannitol phase behavior during freeze-drying using non-invasive raman spectroscopy. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2007;61:131–45.

McCreery RL. Raman spectroscopy for chemical analysis. 1st ed. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2000.

de Waard H, Grasmeijer N, Hinrichs WLJ, Eissens AC, Pfaffenbach PPF, Frijlink HW. Preparation of drug nanocrystals by controlled crystallization: application of a 3-way nozzle to prevent premature crystallization for large scale production. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;38:224–9.

Pikal MJ. Freeze drying. In: Swarbrick J, editor. Encyclopedia of pharmaceutical technology. New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

Rodríguez-Hornedo N, Kelly RC, Sinclair BD, Miller JM. Crystallization: general principles and significance on product development. In: Swarbrick J, editor. Encyclopedia of pharmaceutical technology. New York: Informa healthcare USA, Inc.

Qian F, Tao J, Desikan S, Hussain M, Smith RL. Mechanistic investigation of pluronic(R) based nano-crystalline drug-polymer solid dispersions. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1551–60.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed within the framework of project T5-105 of the Dutch Top Institute Pharma. The authors would like to thank P. Pfaffenbach (Solvay Infra Bad Hönningen GmbH, Hannover, Germany) for his assistance on XRPD analysis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Hans de Waard and Thomas De Beer contributed equally to this paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Waard, H., De Beer, T., Hinrichs, W.L.J. et al. Controlled Crystallization of the Lipophilic Drug Fenofibrate During Freeze-Drying: Elucidation of the Mechanism by In-Line Raman Spectroscopy. AAPS J 12, 569–575 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-010-9215-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-010-9215-z