Abstract

Introduction

Despite promising outcomes, lack of engagement and poor adherence are barriers to treating mental health using digital CBT, particularly in minority groups. After conducting guided focus groups, a current mental health app was adapted to be more inclusive for minorities living with SCD.

Methods

Patients between the ages of 16–35 with SCD who reported experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms were eligible for this study. Once enrolled, participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two versions of a mental health app: 1) the current version designed for the general population or 2) the adapted version. Baseline measures for depression, anxiety, pain, and self-efficacy were completed at the start of the study and again at post-intervention (minimum 4 weeks).

Results

Compared to baseline, mean scores for pain decreased an average of 3.29 (p = 0.03) on a 10-point scale, self-efficacy improved 3.86 points (p = 0.007) and depression symptoms decreased 5.75 points (p = 0.016) for the group that received the adapted app. On average, control participants engaged with the app 5.64 times while the participants in the experimental group engaged 8.50 times (p = 0.40). Regardless of group assignment, a positive relationship (r = 0.47) was shown between app engagement and a change in depression symptoms (p = 0.042).

Discussion

Target enrollment for this study sought to enroll 40 participants. However, after difficulties locating qualified participants, enrollment criteria were adjusted to expand the population pool. Regardless of these efforts, the sample size for this study was still smaller than anticipated (n = 21). Additionally, irrespective of group approximately 40% of participants did not engage with the app. However, despite a small sample size and poor engagement, this study 1) demonstrated the feasibility of implementing socially relevant changes into a mental health app and 2) indicated that participants in the intervention group displayed better outcomes and showed trends for greater app interaction.

Conclusion

These promising results should encourage future researchers to continue exploring ideal adaptations for implementing digital CBT in minority populations. Future studies should also consider implementing post-intervention surveys to help identify common factors relating to a lack of engagement.

Trial registration

This trial (NCT04587661) was registered on August 12th, 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

African Americans living with chronic medical conditions are at high risk for depression and other mental health disorders yet are less likely to be diagnosed or receive treatment than their white counterparts [1, 2]. Left untreated, depression can increase disease severity and risk for mortality [3, 4]. One especially vulnerable group is patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) [5], a genetic blood disorder that primarily affects people of African descent and disproportionately impacts those living in disadvantaged circumstances [6]. Sickle cell causes severe acute and chronic pain, end-organ damage, and early mortality [7].

Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with SCD, those between the ages of 18–30, are at particularly high risk for disease-related complications. This development period, the transition from adolescence to adulthood, is characterized by significant biological and social changes, as well as changes in medical care. Patients will leave their pediatric hematology team, whom they have often received care from for most of their lives and begin working with a new adult care team that is sometimes unfamiliar to the patient. Given the intersection of multiple significant life changes, late adolescence, and young adulthood, for those with SCD this is a tumultuous period, characterized by social vulnerability, increased medical complications, and high health care utilization [8,9,10]. It is not surprising, therefore, that this age group is at high risk for mental health disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors [11, 12]. Comorbid mental health disorders also have a deleterious impact on health behaviors and outcomes in this population. SCD patients with depressive symptoms are less likely to be adherent to therapies that prevent disease progression and are at increased risk of vaso-occlusive events (VOEs) and acute chest syndrome. Increased anxiety is associated with poorer pain-related outcomes, increased risk of pain crises, and greater opioid use. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that effective treatments are deployed to screen for and treat the mental health of AYA with SCD [13].

To address the mental health of AYA with SCD, there is a need for evidence-based mental health treatments that can be delivered in low-resource settings, are easily accessible, and are provided at a low cost. Mental health treatments delivered through mobile technology make it possible to provide high-quality, evidence-based care, at-scale behavioral mental health treatment that reaches patients in under-resourced settings [14, 15]. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective for treating depression and anxiety and can be easily brought to scale at low cost [16]. Several meta-analyses have found digital CBT effective for treating depression and anxiety in white adults [17,18,19]. Although there is limited data on digital CBT in minority populations, a large-scale trial conducted in primary care clinics showed that digital CBT is equally effective for treating depression and anxiety symptoms among African American as for whites [20]. Further, in a pilot randomized trial among adults with SCD, compared to usual care, digital CBT was associated with greater improvements in depressive symptoms and daily pain [21]. Thus, there is early evidence to suggest digital CBT may work not only in SCD but in other minority or underserved patient populations as well.

Despite the promise of digital CBT, lack of uptake and sustained engagement with digital therapies is a significant barrier to widespread use of this technology, particularly in low-resource settings serving minorities [22,23,24]. Digital CBT is consistently associated with high attrition and poor adherence [25,26,27]. Poor uptake and adherence of digital CBT is particularly problematic in SCD where lack of engagement with the treatment can negatively affect its effectiveness [28, 29]. In a pilot study of digital CBT with SCD adults, although patients reported benefits from digital CBT, the average user completed only 3 of 8 possible sessions. Post-study interviews and a focus group revealed that while SCD patients did indeed feel the CBT skills were useful, the content was often not relevant or relatable and did not represent their real-world cultural and health experience. In addition, interventions with this population must address cultural stigma, a well-known barrier to recruitment and retention of racial/ethnic minorities in mental health programs [30]. To advance the field, there is a need for innovative approaches to remediating these barriers to the provision, receipt, and benefit of digital CBT-based mental health services in low-resource settings.

Adaptation of evidence-based practices is often necessary for their successful implementation in different settings. Interventions may need to be tailored to meet the needs of the target population or address differences between the context in which the intervention was originally designed and the one into which it is delivered. We know that when digital interventions have a persuasive, user-centered design and personalized, tailored content, user involvement, adherence, and outcomes are better [14], but it is not yet clear what adaptations are critical to implementation success, and whether these adaptations can effectively address the perception that an intervention is not relatable, or the stigma of mental health treatment. Thus, important next steps for digital CBT are to determine whether it is feasible to incorporate socially relevant changes to a CBT program and whether these adaptations can overcome challenges of uptake and engagement. Therefore, we adapted an existing digital CBT program for mental health by adding images, references, and content representing SCD, chronic pain, and stressors unique to African Americans living with SCD. We then compared the adapted digital CBT to the standard program in a randomized trial of adolescent and young adults with SCD and elevated mental health symptoms.

Methods

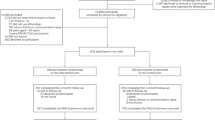

As part of routine clinical care, SCD patients at the University of Pittsburgh Children’s and Adult clinics completed a mental health screener. Initial eligibility for the study included SCD patients between the ages of 16–30 reporting moderate or greater symptoms of anxiety of depression (i.e., Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] or Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-7] > 9). Using these criteria, few patients qualified for the intervention. Eligibility criteria was adjusted to include SCD patients up to age 35 reporting mild or greater symptoms of anxiety or depression (i.e., PHQ-9 or GAD-7 > 4). Patients who met these criteria were identified as potential participants and provided with a brief explanation of the research study. Eligible patients who elected to enroll were randomized, in an equal allocation ratio, into one of two groups receiving mental health treatment via a mobile app. A total of 21 individuals living with SCD enrolled in the study. Group one (n = 11) received a mental health app designed for the general population (Control), while group two (n = 10) received an enhanced version of the same app designed to be more specific to minorities living with SCD (PLUS). A group-specific, asynchronous health coach was also provided via the app. Once participants were given access to the app, they were encouraged to interact with their assigned health coach and familiarize themselves with the app. Both versions of the mobile app provided access to 19 CBT modules and 12 short techniques (< 5 min) that participants could choose from based on their individual needs and engage in at will. Aside from the image representing the module, modules were identical between study arms. Users were able to access and complete these modules and techniques as many times as they wanted throughout the study. Health coaches were available to answer questions and guide participants to appropriate techniques. Engagement reminders were also sent out to inactive participants at least every 3 days for up to 4 reminders. For best results, participants were encouraged to use the app a minimum of 2–3 days/week with 5–7 days/week being ideal. Participants were blinded to their assigned study arm. The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protections Office and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

Adaptations made to enhance the app for SCD

Prior to adapting the app, guided focus groups were conducted to determine ways to enhance the app to increase engagement for minorities living with SCD [31]. Based on the findings of this study and guided by the FRAME, a framework for adapting interventions [32] we identified areas of adaptation related to the content, contextual factors, and the training/education of staff delivering the intervention.

Images and language

Based on these findings from our qualitative work, minor modifications were made to some of the language presented and the images. Specifically, we modified 24% of the images associated with the available techniques within the app to fit more Afrocentric and urban themes. Figure 1 presents four examples of how the standard CBT app images were replaced by images adapted to be more socially inclusive and relevant for the target population.

Comparison of PLUS images to Control images in the mobile app. (A) Four PLUS images with afrocentric and urban themes were modified from the (B) original Control images used on the mobile app. These replacements were adapted to be more socially inclusive and relevant for the target population. Images from (B) are copyright of UPMC Health Plan, Inc. Permission was obtained to use and adapt these images

Introduction video

Consistent with social cognitive theory [33], it was important for patients to know others with SCD were going through the same experience and using the same type of interventions. Consented patients randomized to the SCD adapted arm, the intervention group, received a 5-min video that explained that mental health symptoms for AYA with SCD were common and that cognitive behavioral therapy had been shown to be effective.

Health coach training and messaging

One coach was designated to the PLUS arm who, in addition to 4 weeks of intensive health coach training, also received training specific to working with adolescents and adults with SCD. The PLUS health coach completed an online short course on SCD that included a completion quiz, and received an hour long 1:1 training with an SCD psychologist on best practices for working with individuals with SCD. The PLUS-arm health coaches were also provided with 6 additional text messages specific to SCD that touched on specific wellness topics noted by patients as important, such as emotional health and nutrition. Examples of these messages are:

-

“Learning ways to manage stress can help lower your risk of side effects associated with SCD. What are some ways that you currently manage your stress?”

-

“Did you know that your body has greater nutritional needs than those without SCD?! To help your body function and help decrease pain complications, it’s extra important to eat right. Have you ever examined your diet? Making small changes can have a BIG impact and I’m here to help!”

Measures and timepoints

Measures of depression [PHQ-9], anxiety [GAD-7], pain [0–10 pain scale], and self-efficacy [Sickle Cell Self-Efficacy Scale; SCSES] were assessed at baseline (T1) and at least four weeks post-intervention (T2). Paired T-tests were conducted to differences in these variables from T1 to T2. In addition, mobile app engagement was measured via the number of techniques participants used within the app, as well as the number of messages sent to health coaches between T1 and T2. Mobile app engagement was compared between the control and PLUS arms of the study. Correlation analyses were completed and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to examine potential relationships between engagement and other measures (i.e. depression, anxiety, pain and self-efficacy).

Scoring and interpretation of measures

Depression symptoms were assessed using the PHQ-9 and anxiety symptoms were assessed using the GAD-7. The criteria for both tests were scored using a range from 0 (Not at All) to 3 (Nearly Every Day). Responses to each item are summed to obtain an overall score. Higher scores on these assessments indicate greater symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively. To assess self-efficacy, the Sickle Cell Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES) was utilized. This test consisted of 9 items scored using a range from 1 (Not Sure at All) to 5 (Very Sure). Scores for each item was summed to give an overall score. Greater scores indicated greater levels of self-efficacy. A pain scale was administered to determine average perceived pain. Participants rated their average pain on a scale of 0 (No Pain) to 10 (Severe Pain), over the previous 7 days. User engagement with the app was calculated as the sum of the 1) number of techniques completed and 2) number of messages sent to the assigned health coach. Greater interactions are interpreted as greater engagement.

Data analysis

Means and frequencies were determined for each variable. Chi-square and independent t-tests were conducted, as applicable, to assess group differences at baseline. Independent t-tests were used to compare post-intervention and change scores between groups. Paired t-tests were used within each study arm to analyze changes in pre- and post-intervention scores. Potential relationships between outcome measures were assessed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. All analyses were conducted using R.Version (2023.06.0 + 421).

Results

The sample of enrolled patients was predominantly female, adults, who had at least some high school education or had completed high school. Baseline data and demographic characteristics were not different between Control (n = 11) and PLUS (n = 10) groups (Table 1).

App engagement, as determined by the number of techniques completed within the app in addition to the number of communications with the health coach, was not different between groups. The PLUS participants accessed the app an average of 8.50 times over 4 weeks, while Control participants accessed the app an average of 5.64 times (p = 0.40). Approximately, 40% (n = 4) of PLUS and 36% (n = 4) of Control participants accessed the app 1 or fewer days throughout the 4 weeks. Correlation analysis (Fig. 2) showed a moderate relationship (r = 0.47) between app engagement and the score change in PHQ (p = 0.042).

Figure 2 displays a scatter plot presenting the correlation between app engagement and PHQ change scores (T2-T1).

In the PLUS group (n = 8), significant differences were seen between baseline and post intervention scores for pain (p = 0.03), self-efficacy (p = 0.007) and depression symptoms (p = 0.016). No differences were seen in the Control group between pre and post scores. Neither group had a significant change in anxiety or stigma from baseline to post-intervention exposure (Table 2).

Discussion

Despite high adherence to study follow-up (90.5%), approximately 40% of participants did not engage with the app outside of their initial sign-on date. Group assignment did not appear to significantly influence app engagement. However, on average, participants in the PLUS group had greater engagement. This trend within the PLUS group is promising and supports the notion that population-specific adaptations could indeed enhance user uptake. Increasing the app’s inclusiveness via additional adaptations may be necessary to obtain significant growth in user engagement. For this pilot study, only select portions of the app were adapted to determine the feasibility of making such alterations. Further increasing the app’s relevance to the population would presumably increase user engagement. Additionally, a lower-than-expected sample size could also have contributed to the lack of significance between groups. These assumptions are supported by two secondary findings from the study. First, engagement was shown to be moderately correlated with a change in PHQ scores. Consistent with prior literature, this trend suggests that participants with greater engagement showed greater improvement in depression symptoms [34]. Second, improvements were seen exclusively in the PLUS group for pain, self-efficacy, and depression symptoms.

We are unable to determine whether positive changes seen within the PLUS group are attributable to the alterations made to the intervention. While we attempted to enhance the intervention to be more appealing to minorities living with SCD, very few participants engaged with the app in a way that would have allowed them to experience the full range of augmentations. The lack of engagement seen for this study is consistent with previous studies that have shown poor adherence among this population group [20, 29, 35]. Perhaps a more innovative approach to engage participants is needed for this population. For example, participants for this study were blinded to their group during randomization. Conceivably, if participants knew that they were receiving care more specific to their health condition and/or unique to their experiences as a minority, they would be more likely to explore the intervention for more than what is required for study sign-up. Further, our ability to adapt the app design and content was limited. Initial testing with the app, participants found the app difficult to use and confusing. While the current study demonstrates the feasibility of adapting a current app to increase population relevance, improving the overall app experience may be a first step before adaptation.

Engagement may also be linked in some way to symptom severity and/or the perception of symptom severity [36, 37]. For this study, an educational component regarding participant depression and anxiety scores was not directly provided. Participants may or may not have spoken with their health care providers about their scores and the meaning of those scores. It is plausible that those experiencing mild depression and/or anxiety symptoms may not have felt as though a mental health intervention was necessary, compared to those with more severe symptoms. While we did not have a large enough sample to analyze this type of interaction, it is not an uncommon connection. Numerous behaviors change models recognize that the perception of severity may impact an individual’s desire or motivation to make a change [33, 38]. For example, what is often referred to as the Health Belief Model acknowledges that individuals often need to feel as though their current health status is subjectively severe before choosing to act [39]. Future studies may want to consider an educational component, limit recruitment to those displaying moderate to severe symptoms, or ensure recruitment of a large enough sample size to explore symptom severity and its relationship to intervention engagement.

Despite poor engagement, attrition rates were much lower for this study than what has been shown in previous work. Numerous factors may contribute such as, short study length, follow-up measures that did not require additional clinic visits, as well as text message reminders with a direct link to the post-intervention survey.

The sample size for this study was small, which did not allow for testing of covariates or group interactions. We sought to enroll an additional 20 participants, however, there was not a great enough population within the targeted clinics that qualified for participation. Future work should consider a multi-site approach to ensure a large enough population pool. In addition, our intention was to collect T2 data at four weeks post-intervention exposure, but this proved to be difficult with our present sample. Future studies should prioritize adherence to the follow-up schedule, so that differences between patient engagement are more comparable.

Conclusion

Nevertheless, digital CBT holds promise as a widely available, effective treatment for mental health among AYA with SCD. Given the severe burden untreated depression and anxiety places on this group of patients who already face significant health challenges, it is imperative that these treatments are adapted and implemented in order to meet the needs of young SCD patients. This study provided the groundwork, demonstrating that it is feasible to incorporate and implement adaptations to a current digital CBT app. While tailoring may not be critical to promote uptake of digital CBT, this study shows preliminary evidence that tailoring is a critical part of adapting such interventions to patients with SCD.

Availability of data and materials

The data summary will be available on Clinical Trials.gov and included in a data repository within the NIMH Data Archive ( NCT04587661, STUDY20070307).

References

Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, McGuire T, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995–2005. Med Care. 2008;46(7):668–77.

Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, Manheim LM, Chang RW. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11):1945–52.

Simon GE. Treating depression in patients with chronic disease: recognition and treatment are crucial; depression worsens the course of a chronic illness. The Western journal of medicine. 2001;175(5):292–3.

Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A14.

Jerrell JM, Tripathi A, McIntyre RS. Prevalence and treatment of depression in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: a retrospective cohort study. Primary Care Companion CNS Dis. 2011;13(2):27132.

Adam SS, Flahiff CM, Kamble S, Telen MJ, Reed SD, De Castro LM. Depression, quality of life, and medical resource utilization in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2017;1(23):1983–92.

Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, Gaston MH, Ohene-Frempong K, Krishnamurti L, Smith WR, et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18010.

Stollon NB, Paine CW, Lucas MS, Brumley LD, Poole ES, Peyton T, Grant AW, et al. Transitioning adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult health care: provider perspectives. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37(8):577–83.

Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, Johnson S, Osunkwo I. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(1):116–20.

Jonassaint CR, Jones VL, Leong S, Frierson GM. A systematic review of the association between depression and health care utilization in children and adults with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(1):136–47.

Palermo TM, Riley CA, Mitchell BA. Daily functioning and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease pain: relationship with family and neighborhood socioeconomic distress. J Pain. 2008;9(9):833–40.

Benton TD, Boyd R, Ifeagwu J, Feldtmose E, Smith-Whitley K. Psychiatric diagnosis in adolescents with sickle cell disease: a preliminary report. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(2):111–5.

Pecker LH, Darbari DS. Psychosocial and affective comorbidities in sickle cell disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019;705:1–6.

Jones DJ, Anton M, Gonzalez M, Honeycutt A, Khavjou O, Forehand R, Parent J. Incorporating mobile phone technologies to expand evidence-based care. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(3):281–90.

Schueller SM, Torous J. Scaling evidence-based treatments through digital mental health. Am Psychol. 2020;75(8):1093–104.

Gratzer D, Khalid-Khan F. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychiatric illness. Can Med Assoc J. 2016;188(4):263–72.

Kambeitz Ilankovic L, Rzayeva U, Völkel L, Wenzel J, Weiske J, Jessen F, Reininghaus U, et al. A systematic review of digital and face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. npj Digital Med. 2022;5(1):144.

López-López JA, Davies SR, Caldwell DM, Churchill R, Peters TJ, Tallon D, Dawson S, et al. The process and delivery of CBT for depression in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(12):1937–47.

Reinecke MA, Ryan NE, DuBois DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(1):26–34.

Jonassaint CR, Kang C, Prussien KV, Yarboi J, Sanger MS, Wilson JD, De Castro L, et al. Feasibility of implementing mobile technology-delivered mental health treatment in routine adult sickle cell disease care. Translatl Behav Med. 2020;10(1):58–67.

Jonassaint CR, et al. Feasibility of implementing mobile technology-delivered mental health treatment in routine adult sickle cell disease care. Translatl Behav Med. 2018;10(1):58–67.

Ringle VA, Read KL, Edmunds JM, Brodman DM, Kendall PC, Barg F, Beidas RS. Barriers to and facilitators in the implementation of cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety in the community. Psychiatric Serv. 2015;66(9):appips201400134.

Wolitzky-Taylor K, Fenwick K, Lengnick-Hall R, Grossman J, Bearman SK, Arch J, Miranda J, et al. A Preliminary exploration of the barriers to delivering (and Receiving) exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in adult community mental health settings. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(7):899–911.

Moskalenko MY, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Katapally TR. Barriers to patient interest in internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy: informing e-health policies through quantitative analysis. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(2):139–45.

Egilsson E, Bjarnason R, Njardvik U. Usage and weekly attrition in a smartphone-based health behavior intervention for adolescents: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Formative Res. 2021;5(2):e21432.

Karlson CW, Rapoff MA. Attrition in randomized controlled trials for pediatric chronic conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(7):782–93.

Beshai S, Watson LM, Meadows TJS, Soucy JN. Perceptions of cognitive-behavioral therapy and antidepressant medication for depression after brief psychoeducation: examining shifts in attitudes. Behav Ther. 2019;50(5):851–63.

Daniels S. Cognitive behavioral therapy in patients with sickle cell disease. Creat Nurs. 2015;21(1):38–46.

Sil S, Lai K, Lee JL, Gilleland-Marchak J, Thompson B, Cohen LL, Lane PA, et al. Engagement in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain management is associated with reductions in healthcare utilization in pediatric sickle cell disease. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):418–418.

Jonassaint CR, et al. Racial differences in the effectiveness of internet-delivered mental health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):490–7.

Nikolajski C, et al. Tailoring a digital mental health program for patients with sickle cell disease: qualitative study. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:e44216.

Wiltsey Stirman S, et al. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58.

Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015;30(6):566–76.

Venkatesan A, Forster B, Rao P, Miller M, Scahill M. Improvements in depression outcomes following a digital cognitive behavioral therapy intervention in a polychronic population: retrospective study. JMIR Formative Research. 2022;6(7):e38005.

Sil S, Lai K, Lee JL, Gilleland Marchak J, Thompson B, Cohen L, Lane P, et al. Preliminary evaluation of the clinical implementation of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain management in pediatric sickle cell disease. Complement Ther Med. 2020;49:102348.

Glenn D, Golinelli D, Rose RD, Roy-Byrne P, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Bystritksy A, et al. Who gets the most out of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders? The role of treatment dose and patient engagement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(4):639–49.

Tsirmpas C, Andrikopoulos D, Fatouros P, Eleftheriou G, Anguera JA, Kontoangelos K, Papageorgiou C. Feasibility, engagement, and preliminary clinical outcomes of a digital biodata-driven intervention for anxiety and depression. Front Digital Health. 2022;4:868970.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660–80.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, R34MH125152-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN, EP, CRJ, and JO played crucial roles in writing the main manuscript text, performing data analysis, and employing analytical methods. EP, EN, CRJ, and JO contributed to the interpretation of the results and provided valuable insights into the implications of the findings. CRJ, as the principal investigator, oversaw the execution and design of the study, outlining the manuscript and its coherence with research objectives, and actively contributed to data analysis. EN, EP, LC, JP, TP, CN, MT, CH, ES and CRJ all contributed to the design and conduct of the study, including collection of study related data, and reviewed final versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods in this study performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (STUDY20070307). Participation in the study was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to enrolling in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nardo, E.V., Parchuri, E., O’Brien, J.A. et al. The effect of an adapted digital mental health intervention for sickle cell disease on engagement: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Digit Health 1, 54 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00051-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00051-y