Abstract

Background

Biotechnological syndromes refer to the illnesses that arise at the intersection of human physiology and digital technology. Now that we experience health and illness through so much technology (e.g. wearables, telemedicine, implanted devices), the medium is redefining our expression of symptoms, the observable signs of pathology and the range of diseases that may occur. Here, we systematically review all case reports describing illnesses related to digital technology in the past ten years, in order to identify novel biotechnological syndromes, map out new causal pathways of disease, and identify gaps in care that have disadvantaged a community of patients suffering from these digital complaints.

Methods

PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane Library and Web of Science were searched for case reports and case series that described patient cases involving biotechnological syndromes from 01/01/2012 to 01/02/2022. For inclusion the technology had to play a causative role in the disease process and had to be digital (as opposed to simple electronic).

Results

Our search returned 7742 articles, 1373 duplicates were removed, 671 met the criteria for full review and 372 were included in the results. Results were categorised by specialty, demonstrating that syndromes were most common in Cardiology (n = 162), Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (n = 36), and Emergency and Trauma (n = 26).

Discussion

The 372 unique patient cases demonstrated a range of severity from mild (e.g., injuries related to Pokemon Go) to moderate (e.g. pacemaker-generated rib fractures) and severe (e.g. ventilator software bugs causing cardiac arrest). Syndromes resulted from both consumer technology (e.g. gaming addictions) and medical technologies (e.g. errors in spinal stimulators). Cases occurred at both the individual level (e.g. faulty insulin pumps) and at the population level (e.g. harm from healthcare cyberattacks).

Limitations

This was a retrospective systematic review of heterogeneous reports, written in English, which may only reflect a small proportion of true prevalence rates in the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital technologies are reshaping our bodies, our minds and our experience of health and disease. We spend a great deal of time building these new tools, examining them, and celebrating their feats, yet we have been less attentive to the ways in which these technologies are rebuilding us. The screens we are staring into daily are reshaping our eyes [1]; our backs bend into our devices stretching our spines into new postures [2]; our minds twist to adapt new modes of information processing [3]; all the while our tapping fingers are reshaping our tendons and joints [4, 5]. The implantation and ingestion of digital technologies into the body has further expanded the remit of possible technology-related bodily phenomena [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Our psychology and physicality are constantly in flux, moulded by our shifting environment that is evermore defined by digitisation as we carry out dual online and offline lives.

Within academia, the field of digital health has made great advances in exploring how we can use technology to improve human wellbeing. In our work, we are concerned with the reverse direction of this relationship and with the medium of technology itself. Ever since Nietzsche’s contemporaries commented on his new style of writing after being forced to use a typewriter, technologists have explored the reciprocal relationship between humans and their machines—seeing that the tools we create tend to reshape our capacities as we work through them [3, 12]. As we increasingly experience health and illness through technology (wearables, implanted devices etc.), the medium is redefining our expression of symptoms, the observable signs of pathology, and the range of possible diseases that may occur.

In healthcare, implantable devices can malfunction manifesting as previously unseen syndromes. Our physicality becomes vulnerable to electromagnetic interference and must adapt to new biometric materials. To capture these new possibilities, we propose that “Biotechnological syndromes” should reference syndromes that emerge at the intersection of human health and technology. The term is deliberately broad to encompass cases as different as vertigo secondary to haptic-integrated virtual reality [9] and cardiac arrest due to ventilator software bugs [13].

Here we argue that the landscape of healthcare biotechnology is now so complex that digital complaints can no longer be managed as an offshoot of an existing clinical domain. We see this need manifesting across specialties—psychiatrists are responding to unusual psychological sequelae resulting from digital technologies (e.g., digital hoarding [14]), ophthalmologists are observing advanced rates myopia related to screen-use [1], and neurologists are witnessing new neuropsychiatric manifestations from errors in implanted Deep Brain Stimulators (DBS) [8, 15,16,17,18,19]. Though these presentations may seem heterogeneous, the underlying mechanisms are often shared and require examination through the lens of their similarities e.g., software bugs in pacemakers may also occur in spinal stimulators. Positioning biotechnological syndromes together as a group, instead of in the margins of existing specialties, allows us to draw cross-disciplinary intelligence and examine the evolving causal pathways to disease that begin with technology and end in biology.

Biotechnological syndromes may affect individual patients (e.g. phantom shocks [7]), or groups of patients simultaneously (e.g., wireless networks impacting the integrity of ECG investigations and cardiac care [20]). Population level impact may occur in the home where patients rely on the cloud to tailor care, or within hospital settings where technological failures in drug-delivery systems can place patient life at risk [21, 22].

While whole populations may be at risk, not all populations are affected equally, with biotechnological complaints being unevenly distributed amongst the population, compounding pre-existing health inequalities [23,24,25,26]. For example, the gender-based differences in cybersickness related to virtual environments has been attributed to androcentric design of augmented realities [27]. The way in which new technologies are created and distributed is determining how the burden of biotechnological disease falls amongst the population.

Research aim

In a comprehensive survey of case reports across the medical literature, we present a cross-disciplinary analysis of reported cases that relate to digital technology and meet the criteria of a ‘Biotechnological syndrome’. We have adopted the term ‘Biotechnological syndrome’, as we are concerned with issues evolving from the foundational root of Biotechnology—defined as intersection between the natural and engineering sciences [28]. Hence, in our study we define a Biotechnological syndrome as clinical symptoms and signs that emerge due to interaction with technologies stemming from the natural and engineering sciences. We do not define a set of included technologies as the landscape of healthcare technology is constantly changing and such a definition would soon become redundant, instead we have defined inclusion by the underlying technical mechanisms that drive function.

Our research is also written through a clinical lens, as we are interested in the challenges healthcare professionals face when managing clinical cases that involve technological mechanisms not covered in their training (e.g. radio-communication, computer programming). The pathology that underpins a Biotechnological syndrome must therefore originate in a technology emerging at the intersection of the natural and engineering sciences, and the technology itself must play a causative role in the process of disease that manifests in a clinical presentation. As our research is focused on the last ten years, a period previously described as the ‘Decade of the Internet of Things’, we expose issues associated with modern biotechnological features, such as connected intelligent medical devices and the ‘Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)’ [29, 30]. Through our evaluation of the case report literature we aim to explore the following research questions:

-

I.

What are the cases of Biotechnological syndromes?

-

II.

What is the aetiology that underpins Biotechnological syndromes?

-

III.

What gaps exist in medical education and training that impede effective treatment of Biotechnological syndromes?

In addressing these questions we seek to draw connections between similar biotechnological cases occurring in disconnected specialties; illuminate any current gaps in medical knowledge regarding these syndromes; and better understand these mechanisms of disease.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane Library and Web of Science for reports that described patient cases involving biotechnological syndromes in the past ten years (01/01/2012—31/12/2022), adhering to PRISMA Guidelines for systematic reviews and mirroring the methods of previous authors systematically reviewing case report literature (Fig. 1 and Supplementary A-B) [1]. We were interested in digital devices (e.g., smartphones) as opposed to all electronic devices (e.g., lamps) and therefore parameterised our definition of technology. We utilise the definition of digital technologies in healthcare provided by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which states—“Digital health technologies use computing platforms, connectivity, software, and sensors for health care and related uses. These technologies span a wide range of uses, from applications in general wellness to applications as a medical device”. In some cases it may not be possible to ascertain whether a technology was digital or simply electronic, for example in the case of e-Cigarettes. At their most basic these e-cigarettes are battery powered vaporizers of nicotinic liquid, but at their most advanced they are accompanied by connectivity features that allow them to be synced with smartphones e.g. Smokio Vapes [31]. Thus, simple designs may not be considered a digital technology yet in connected models, where an app may influence inhalation frequency, the technology may affect lung disease severity. If we could not determine whether a device was purely electronic, or had digital elements, we opted to retain it for completeness.

Data extraction

One reviewer extracted data, from which all authors collaboratively reviewed the included studies and evaluated the role of the technology in the patient’s clinical presentation.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Study Type: A case report, case series or systematic review of cases.

-

2.

Selecting Digital Technologies: (a) We excluded anything non-electronic e.g., hip prosthesis, (b) We excluded technology that was electronic, but had no digital component (e.g., surgical diathermy tools) [29]; (c) We retained technology that was clearly digital (e.g., smartphones), and electronic technologies where the digital element could not be ascertained (e.g. e-Cigarettes).

-

3.

Disease Causal Pathway: The technology had to play a role in the causal pathway of disease, thus excluding cases where the presence of technology was incidental or unrelated.

Our results are structured under the clinical subspecialties, determined by the speciality that played the main role in patient management. Throughout the manuscript patients are referenced by age and sex e.g. 50F (age 50, sex female).

Role of funding source

The research was supported by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI Grant Reference Number EP/S021612/1) who fund the doctoral research of the corresponding author.

Results

Our systematic search returned 7742 articles, from which 1376 duplicates were removed, 671 met the criteria for full text review and 372 were included in the final results.

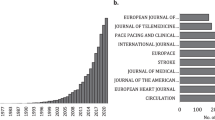

Medical specialties

Table 1 details the number of case reports by specialty, demonstrating that digital pathologies were most common in Cardiology (n = 162), Microbiology and Infectious diseases (n = 36), and Emergency and Trauma (n = 26). There was a range of clinical severity; (i) mild e.g. soft tissue injuries related using Segway vehicles [32] (ii) moderate e.g. traumatic drone related injuries [33], explosions from electronic cigarettes [34], and (iii) severe e.g. hypoglycaemic death related to an insulin pump [35].

The most severe cases presented as life-threatening injury. One report described a low-impact virtual reality fall, which resulted in spinal cord injury [36]. Nishihama and colleagues described a 65F using a sensor-augmented insulin pump for diabetes who experienced repeat dosing errors related to technological issues, culminating in sudden death due to severe hypoglycaemia [35]. In paediatrics, Duff and colleagues report two cases of circulatory arrest due to failures of ventricular assist devices (VADs) [37]. The authors highlight the diagnostic challenge inherent within these cases where the devices produce non-pulsatile flow rendering traditional clinical assessments (pulse and blood pressure) obsolete [37]. In the sections below we divide our analysis of the clinical cases by those caused by (i) consumer technology (e.g., gaming devices) and (ii) healthcare technology (e.g., glucose sensors).

Medical specialties—consumer technology

Biotechnological syndromes may arise from our interactions with technology outside of the healthcare setting, such as injuries from tasers [38,39,40], e-Cigarettes [41, 42] and exercise machines [43]. Computing technologies were common culprits of these harms, such as the 64F who developed third-degree burns requiring partial foot amputation due to an overheating laptop [44]. Tremaine and Avram highlighted adverse dermatological events related to energy-based devices (including lasers and radiofrequency technologies) [45]. Aniruddha and colleagues report a 23 M with progressive visual loss due to laser pointer–induced maculopathy [46]. Bellal and Armstrong reported injuries presenting to their trauma centre sustained secondary to gameplay with augmented reality-based applications [47].

Medical specialties – healthcare technologies

Pacemakers were the most common implanted medical technology described in the literature, with complications including: runaway pacemakers [48]; pacemaker electrical storms [49]; Reel’s syndrome, Twiddler’s syndrome and Ratchet Syndrome – all referring to complications arising from the displacement of wire based systems [49,50,51]. Now that pacemaker technology has been extended to other domains, such as Deep Brain Stimulators (DBS) in neurology and gastric stimulators in gastroenterology [52], previously reported pacemaker complications are manifesting in the context of these new devices e.g. the neurological patient with an intrathecal baclofen pump who presented with withdrawal as a result of Twiddler’s Syndrome [53].

Device malfunctions materialise differently depending on their physiological setting. DBS case reports illustrated the range of neuropsychiatric symptoms resulting from technological failures including compulsive skin-picking [16], headache [17], keyboard-typing dysfunction [15], choreiform dyskinesia and intense sadness [8]. Complications of Vagal Nerve Stimulators (VNS) often presented with an aura of throat and respiratory symptoms [54] and failures of spinal cord stimulators presented with varied symptoms and signs, including tinnitus [55] and refractory sexual arousal [56].

A high number of device-related infections involved unusual pathogens: listeria bacteraemia originating from a pacemaker [57] and life-threatening implications of necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis originating from LVAD [58]. Further, allergy to pacemaker compounds and infection can be hard to distinguish, as highlighted in Robledo-Nolasco’s paper regarding the 17F treated with antibiotics for 18 months for a presumed pacemaker infection – only to later find this was a case of nickel rejection [59]. Xu and colleagues explore this topic further and discuss ‘Graft-versus-host disease’ of implanted devices [60].

In hospitals, failures in drug-delivery systems are of particular concern given the increasing prevalence of cyberattacks on healthcare infrastructure [22, 61]. The example of pathology arising from a malfunctioning intrathecal medication system, highlights the danger that compromised drug delivery equipment poses to patients [62]. Further, Faulds and colleagues describe hypoglycaemic emergencies resulting from insulin pump malfunctions [21], and patient harm can arise from malfunctions in robotic assistive technologies for surgery [63].

Surgical specialties

In the surgical specialities, biotechnological phenomena frequently materialised as Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) complaints largely related to cochlear implants (CI) (Table 2). We encountered twelve papers focused on CI complications, uncovering (i) a 26F with facial pain, rash and dizziness [64] and (ii) a 28 M with auditory disturbance and seizures, which fully resolved following device removal [65].

In Obstetrics, the management of pregnant patients with implanted devices posed additional challenges; Patel and colleagues reported discuss the complexities of managing pain for an obstetric patient with a spinal cord stimulator requiring an urgent caesarean section [66]. Further, Tang and Hyman report a 34F who developed syncope after the administration of labour epidural analgesia, thought to have interacted with her in-situ VNS [67].

Psychiatry

Table 3 provides the full list of psychiatric cases, in which there was a mixed focus on consumer and medical devices. In the consumer space, we see new manifestations of old psychiatric processes that have been transformed through technology, such as ‘digitised’ OCD symptoms related to online behaviour [68]. Komendi and colleagues explore how excessive smartphone use can be evaluated through traditional diagnostic frameworks for addiction [69]. Sharma and Mahapatra discuss a 16 M who developed maladaptive daydreaming and internet gaming addiction following extensive cyberbullying [70]. Cases involving healthcare technologies included DBS malfunctions which frequently presented with psychological symptoms [18], however in many of these cases mental illness was a co-morbidity of the disease the DBS was treating (hence distinguishing one from the other proved challenging).

Psychological effects of a technology may result from wider social effects, such as the 28 M whose LVAD was repeatedly mistaken for an explosive device and faced repeated accusations of being a “suicide bomber” [71]. Al-Shaiji et al. describe the ‘psychological disturbances’ of three females who underwent sacral neuromodulation for lower urinary tract dysfunction [72]. While the article has an unfortunate flavour of psycho-pathologising female patients, it does raise an important question of the psychological impact of these technologies.

Cross-disciplinary & public health

One challenge for practitioners is that biotechnological syndromes manifesting in their specialty, may result from a technology initiated within an unfamiliar domain. For example, (i) Refractory sexual arousal subsequent to a neurostimulator [56]; (ii) New onset tinnitus following spinal stimulator implantation [55]; (iii) Abdominal spasms resulting from pacemaker phrenic nerve stimulation [73]; (iv) Arm pain secondary to brachial plexus injury caused by impingement from a loop of ICD lead [74].

In addition, biotechnological syndromes may be hard to detect due to a confusion of cause and effect. Sommer et al. report a remarkable case in which a wheelchair bound patient with a worsening history of dysarthria, one day surprised his carer by regaining his clarity of speech and his ability to walk [75]. On noting the concurrent battery depletion of the patient’s DBS, it was uncovered that the symptoms that had been assigned to disease progression, in fact related to incorrect device settings.

Lastly, biotechnological syndromes may affect whole populations at a time. Hardell et al. described radiofrequency radiation from base stations causing high levels in an apartment in Stockholm, rendering the accommodation unliveable [76]. Chung et al. describe the impact of a Wireless Local Area Network on ECG machines, hindering the effective evaluation of cardiac patients [20]. Further, for pumps that rely on electronic programming to correctly control concentrated medications, their vulnerability to faults, EM interference and cybersecurity exploits is of paramount concern [21, 35, 62].

Those working in health disparities may examine the impact of digitisation on marginalised groups, for example home based telemetric medicine is dependent on signal coverage – a infrastructural necessity that correlates closely with urbanity and socioeconomic affluence [77, 78]. Patient’s with higher body habitus may be at increased risk of device failures, as suggested by Katsaras et al. who consider the impact of body habitus on loss of telemetric device function in their 63F pacemaker-dependant patient [78]. Women and girls face additional risks, particular regarding technology-facilitated abuse, and psychiatric misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatements [25, 79,80,81,82].

Discussion

The biotechnological case reports we have identified only represent those cases thought interesting enough to write up and report in the peer-reviewed literature. The scope of true disease is likely far larger. We now turn to a series of themes that emerged from our evaluation of the case reports uncovered in our work.

Causal pathways of biotechnological syndromes

The factors present across the causal pathways of biotechnological disease included heat (linked to CPU, GPU or other device features), EM interference, connectivity features, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, software and hardware faults – all of which interacted with human physiology culminating evolving syndromes influenced by shifting technological and biological factors. In Fig. 2, we provide an illustration of the causal pathways of these biotechnological diseases, mapping these processes from their shared source pathology (e.g., software bug) to their manifestation in patient symptoms and signs.

Khan and colleagues provided a useful example of mapping the causal pathway of a biotechnological syndrome through the case of a pacemaker patient, where a software storage error resulted in inappropriate pacing inhibition, presenting as frequent episodes of light-headedness for the patient [83]. In this instant, the disease pathway was: storage software bug, inappropriate pacing inhibition, poor circulatory flow and syncope. In the case of two paediatric deaths, Duff and colleagues further discuss device-related aetiologies, including drivelines and battery issues [37].

Lastly, automation appeared to be a particular concern. Dufour et al. presented a case series of patient illnesses that related to autonomous decisions taken by ventilators on an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [13]. The silent takeover of commands by the ventilator, without clinicians being made aware, manifested in complex patient pathology that the attending doctors struggled to interpret [13].

Electromagnetic interference and Electric smog

Electromagnetic (EM) interference refers to any EM field signal that can be detected by device circuitry. Dunker et al. refer to these phenomena as ‘Electric smog’ and describe a variety of mechanisms that attempt to resolve interference (pseudo-faraday cage, pan methods) [84]. In emergencies EM interactions may be hard to avoid, such as for the 64 M who experienced tremor as a malfunction of his DBS following interference from external defibrillation performed during cardiac arrest [19]. Furthermore, given the growth of the Internet of Things (IoT), the potential for EM interactions is increasing. Sources of EM interference that caused patient illness included wireless networks [20], swimming pool generators [85], water pumps [86], electrostatic discharge from fleece clothing [87], co-existing implanted devices [88], surgical equipment [89], plastic toys [90], hot tubs [91], electrical installations [92] and consumer devices such as Fitbits [93]. Asher et al. describe a case of a patient’s e-cigarette interacting with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), and a 55F with an ICD which reverted to magnet mode due to interference with the patient’s fitness watch [93]. Lastly, Wight et al. present a case of EM interference from electrolysis within the chlorination systems of swimming pools, uncovered in the case of a 41F whose inappropriate pacemaker shocks correlated with her time swimming in the pool [94].

End of Battery Life (EBOL) pathology

Over the next few years many devices will face battery depletion, particularly impacting neuropsychiatric patients for whom deep brain stimulation (DBS) and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) were approved in the last two decades, and EOBL is estimated at 6–10 years [95]. Pardo described the issues that neuropsychiatric patients will have as they face EOBL, exampled by the case of a middle-aged patient with bipolar disorder who relapsed following EOBL of her device—raising the question of whether neuropsychiatric device EBOL should be treated as a psychiatric emergency [95].

Listening to the device vs. the patients

Throughout these stories patient voices are consistently heard insisting there is something wrong with their device, to find themselves dismissed due to ‘normal’ findings from device interrogation. Such was the case for a pregnant patient with a cochlear implant who suffered for 8 months complaining of dizziness, facial twitches, and pain, only to be informed that the cause was not the device as there was no malfunction picked up on external testing [64]. The source wasn’t found until later on during a surgical procedure, when a tear along the electrode coating was identified and the electrode was found pressed up against the facial nerve [64]. Our understanding of emerging technologies is constantly advancing, and we do not currently have the research knowledge, clinical training or investigations required to provide all the answers when the technology goes wrong. It is imperative therefore that the patient perspective takes precedent, and that their subjective experience is not treated secondary to device interrogations which may not capture all relevant information [64]. Given that previous research has demonstrated that the unconscious biases of clinicians tend fall along lines of gender, class, and race, it will be important to explore how device issues are managed through a lens of health equity [23,24,25, 27, 82].

Recommendations

Research & training

Each case in this review warrants consideration if we are to understand these illnesses better. With each new agent we have introduced to the body, we have potentiated a range of syndromes that have not existed before. In several cases, we discussed the challenges of differentiating device-related symptoms from disease-related phenomena. Devices are placed local to the anatomical region central to the disease process, thus their malfunctions may mimic the underlying disease process. Through effective research we may learn to distinguish between the device pathology and disease pathology, and ensure patients are correcting diagnosed and supported.

Digital updates to clinical assessments

Technological features should be incorporated into each stage of the patient journey. During history taking, clinicians would benefit from knowing the characteristic symptoms and auras of device failure, such as the respiratory symptoms described by patients experiencing VNS failures [96]. We have uncovered clinical signs specific to technology, which would be useful in clinical examination (e.g. a 26F where the positive Tinel’s sign over the ICD generator helped inform a diagnosis of brachial nerve injury secondary to ICD impingement [74]). Risk factors for digital diseases may also be helpful to identify and signpost e.g. manual labour occupations may increase likelihood of Reel syndrome and pacemaker malfunction. Lastly, at present clinicians are limited in the investigations they can use to evaluate biotechnological syndromes, highlighted in a report of a malfunctioning DBS where the presence of largely normal blood tests and imaging demonstrated that hardware faults may not be captured by standard physiological investigations [8].

Digital updates to post-mortems

Presently, we do not have a clinical surveillance system for tracking biotechnological deaths. In 2022 The United Kingdom Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath) produced guidelines on autopsy practice, offering tailored recommendations on post-mortems that involve an implanted medical device [97]. While an excellent move in the right direction, many death certificates are not completed by pathologists—it is the trainee doctors who need to know to how to code for the examples provided in this guidance. Further, the RCPath guidance tends to focus on static devices (e.g., hip prosthesis), as opposed to the digital forensics of software-integrated devices, and issues of cybersecurity are not mentioned throughout the document [97].

Treatment guidelines

Applications such as MicroGuide, which is used in 91 of the 152 acute hospital trusts in the NHS in England, provide antibiotic guidelines categorised by physiological system e.g. gastro-intestinal in appendicitis [98]. Technological devices are currently not a listed category under this guidance, the evidence we have presented suggests this is warranted. In addition, life support guidelines need to be adapted for device-dependant patients, highlighted by the case reports of paediatric cardiac arrests in which the non-pulsatile flow devices precluded the evaluation of pulse and blood pressure [37].

Cybersecurity & multidisciplinary solutions

Software malfunctions that put patients at risk by incorrectly over-predicting battery life present a concerning example of how software errors could prove fatal [99]. The increasingly remote nature of device monitoring increases the vulnerability of these systems, evidenced in 2018 when vulnerabilities associated with the Internet connection of Medtronic programmers were exposed [99]. Further cases have described the concerns of medical hacking, both in terms of individual devices but also cyberattacks on hospitals [11, 22]. Cyberattacks are often not understood as clinical attacks, yet to truly understand these digital threats they must be viewed through the lens of clinical consequences and as a public health risk.

Limitations

Our methodological approach is limited, by the fact it is a retrospective systematic review of heterogeneous reports, written in English, which may only reflect a small proportion of true prevalence rates in the population. In addition, by choosing to focus on individual case reports we have not covered the extent of literature that describes possible side effects of medical devices (e.g. from clinical trials) and the trends in adverse device events manifesting in the population (e.g. from the FDA MAUDE database) [100]. While acknowledging that this will neglect one sub-domain of the literature, we have taken this approach in order to centre the clinical experience, which differs from existing research on device complications that is often reported by manufacturers and regulators [100].

Conclusion

New medical fields have historically emerged in response to the changing causal landscape of disease e.g., toxicology, infectious diseases. As opposed to focusing on one domain of the body, these disciplines have specialised in a mechanism of disease and become expert in how it manifests within each bodily system. We propose that a similar approach is needed for the new phenomenon of biotechnological pathology. Parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that we cannot see are potentially interacting with our internal and external environment influencing our health. Pathology may be manifesting through accidental processes that we may be blind to, malicious hacks that we may be ignorant of, or new causal pathways that we are yet to uncover. Amongst the biotechnological syndromes that were reviewed new figures appeared in the causal pathway of illness: hardware and software faults, cybersecurity exploits, microbiology of metallic implants, electromagnetic interference, connectivity complications, and sequalae relating to online experiences. These are the new processes that are now interacting with human anatomy and physiology, and they require their own clinical home to garner the exploration they urgently warrant.

Availability of data and materials

All information regarding data and materials is provided in the supplementary material, where details of the database and literature search can be found.

References

Foreman J, Salim AT, Praveen A, Fonseka D, Ting DSW, Guang He M, et al. Association between digital smart device use and myopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(12):e806–18.

Park J, Kim J, Kim J, Kim K, Kim N, Choi I, et al. The effects of heavy smartphone use on the cervical angle, pain threshold of neck muscles and depression. Adv Sci Technol Letters. 2015;91:12–7 (Bioscience and Medical Research).

Carr N. How the internet is changing the way we think, read and remember. 1st ed. Atlantic Books. 2022. p. 288.

Sharan D, Mohandoss M, Ranganathan R, Jose J. Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Upper Extremities Due to Extensive Usage of Handheld Devices. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2014;26(1):22.

Kim W, Kim Y, Park HS. In Vivo Measurement of Thumb Joint Reaction Forces During Smartphone Manipulation: A Biomechanical Analysis. J Orthop Res. 2019;37(11):2437–44.

Fram BR, Rivlin M, Beredjiklian PK. On Emerging Technology: What to Know When Your Patient Has a Microchip in His Hand. J Hand Surg. 2020;45(7):645–9.

Hairston DR, de Similien RH, Himelhoch S, Forrester A. Treatment of phantom shocks: A case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2019;54(3):181–7.

Straw I, Ashworth C, Radford N. When brain devices go wrong: a patient with a malfunctioning deep brain stimulator (DBS) presents to the emergency department. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(12):e252305. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2022-252305.

Viirre E, Ellisman M. Vertigo in virtual reality with haptics: case report. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6(4):429–31.

South L, Borkin M. Ethical Considerations of Photosensitive Epilepsy in Mixed Reality. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/y32td.

Chunxiao Li, Raghunathan A, Jha NK. "Hijacking an insulin pump: Security attacks and defenses for a diabetes therapy system," 2011 IEEE 13th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services, Columbia, MO, USA, 2011, pp. 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1109/HEALTH.2011.6026732.

Bosanquet T. Henry James at Work. USA: University of Michigan Press; p. 180. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.98996.

Dufour N, Fadel F, Gelée B, Dubost JL, Ardiot S, Di Donato P, et al. When a ventilator takes autonomous decisions without seeking approbation nor warning clinicians: A case series. Int Med Case Rep J. 2020;13:521–9.

van Bennekom MJ, et al. A Case of Digital Hoarding. Case Reports. 2015;2015:bcr2015210814. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-210814.

Wong JK, Armstrong MJ, Almeida L, Wagle Shukla A, Patterson A, Okun MS, et al. Case Report: Globus Pallidus Internus (GPi) Deep Brain Stimulation Induced Keyboard Typing Dysfunction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:583441.

Chang CH, Chen SY, Tsai ST, Tsai HC. Compulsive skin-picking behaviour after deep brain stimulation in a patient with refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(36):e8012.

Luck T, Kusyk DM, Whiting D. Headache as a Presenting Symptom of Deep Brain Stimulator Generator Failure. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16726.

Kinoshitaet al. Turning on the left side electrode changed depressive state to manic state in a parkinson’s disease patient who received bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neuroscience. 2018.

Davis G, Levine Z. Deep brain stimulation generator failure due to external defibrillation in a patient with essential tremor. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2021;99(1):38–9.

Chung S, Yi J, Park SW. Electromagnetic interference of wireless local area network on electrocardiogram monitoring system: a case report. Korean Circ J. 2013;43(3):187–8.

Faulds ER, Wyne KL, Buschur EO, McDaniel J, Dungan K. Insulin pump malfunction during hospitalization: two case reports. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(6):399–403.

Dameff C, et al. Cyber Disaster Medicine: A New Frontier for Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(5):642–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.11.011. (PubMed).

Straw I. The automation of bias in medical Artificial Intelligence (AI): Decoding the past to create a better future. Artif Intell Med. 2020;110:101965.

Straw I, Callison-Burch C. Artificial Intelligence in mental health and the biases of language based models. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0240376.

Straw I, Wu H. Investigating for bias in healthcare algorithms: a sex-stratified analysis of supervised machine learning models in liver disease prediction. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2022;29(1):e100457. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100457.

Carruthers R, et al. Representational Ethical Model Calibration. Npj Digital Med. 2022;5(1):1–9.

Stanney K, Fidopiastis C, Foster L. Virtual Reality Is Sexist: But It Does Not Have to Be. Front Robot AI. 2020;31(7):4.

IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). Online version (2019) created by S. J. Chalk. ISBN 0–9678550–9–8. https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.B00666. Retrieved July 2023.

Brass I, Straw I, Mkwashi A, Charles I, Soares A, Steer C. Emerging Digital Technologies in Patient Care: Dealing with connected, intelligent medical device vulnerabilities and failures in the healthcare sector. 2023. Workshop Report London: PETRAS National Centre of Excellence in IoT Systems Cybersecurity. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8011139.

Ud Din, Ikram, et al. A Decade of Internet of Things: Analysis in the Light of Healthcare Applications. IEEE Access. 2019;7:89967–79. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2927082. Workshop Report London.

Pearson JL, Elmasry H, Das B, Smiley SL, Rubin LF, DeAtley T, et al. Comparison of Ecological Momentary Assessment Versus Direct Measurement of E-Cigarette Use With a Bluetooth-Enabled E-Cigarette: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(5):e84.

Barnes J, Webb M, Holland J. The quickest way to A&E may be via the Segway. BMJ Case Reports. 2013.

Moskowitz EE, Siegel-Richman YM, Hertner G, Schroeppel T. Aerial drone misadventure: A novel case of trauma resulting in ocular globe rupture. Am J Ophthalmol Case Reports. 2018;10:35–7.

Dekhou A, Oska N, Partiali B, Johnson J, Chung MT, Folbe A. E-Cigarette Burns and Explosions: What are the Patterns of Oromaxillofacial Injury? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79(8):1723–30.

Nishihama K, Eguchi K, Maki K, Okano Y, Tanaka S, Inoue C, et al. Sudden death associated with severe hypoglycemia in a diabetic patient during sensor-augmented pump therapy with the predictive low glucose management system. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e928090. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.928090.

Warner N, Teo JT. Neurological injury from virtual reality mishap. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(10):e243424.

Duff JP, Decaen A, Guerra GG, Lequier L, Buchholz H. Diagnosis and management of circulatory arrest in pediatric ventricular assist device patients: presentation of two cases and suggested guidelines. Resuscitation. 2013;84(5):702–5.

Gleason JB, Ahmad I. TASER® Electronic Control Device-Induced Rhabdomyolysis and Renal Failure: A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(10):HD01-2.

Campbell F, Clark S. Penetrating facial trauma from a Taser barb. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(2):188–9.

Sanford JM, Jacobs GJ, Roe EJ, Terndrup TE. Two patients subdued with a TASER® device: cases and review of complications. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(1):28–32.

Walsh K, Sheikh Z, Johal K, Khwaja N. Rare case of accidental fire and burns caused by e-cigarette batteries. BMJ Case Reports. 2016.

Borchert DH, Kelm H, Morean M, Tannapfel A. Reporting of pneumothorax in association with vaping devices and electronic cigarettes. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(12):e247844.

Lawrensia S, Henrina J, Cahyadi A. CrossFit-Induced Rhabdomyolysis in a Young Healthy Indonesian Male. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14723.

Paprottka FJ, Machens HG, Lohmeyer JA. Third-degree burn leading to partial foot amputation–why a notebook is no laptop. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(8):1119–22.

Tremaine AM, Avram MM. FDA MAUDE data on complications with lasers, light sources, and energy-based devices. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47(2):133–40.

Agarwal A, Jindal Ak, Anjani G, Suri D, Freund Kb, Gupta V. Self-Inflicted Laser-Induced Maculopathy Masquerading As Posterior Uveitis In A Patient With Suspected Igg4-Related Disease. Retinal Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16(2):226–32.

Joseph B, Armstrong DG. Potential perils of peri-Pokémon perambulation: The dark reality of augmented reality? Oxf Med Case Reports. 2016;2016(10):265–6.

Gul A, Sheikh MA, Rao A. Runaway pacemaker. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(3):e225411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-225411.

Uppal A, Kathuria S, Shah B, Trehan V. Riata lead failure manifests as electrical storm with lead parameters showing unique postural variations: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021;5(12):ytab491.

Bazoukis G, Kollias G, Tse G, Saplaouras A, Mililis P, Sakellaropoulou A, et al. Reel syndrome—An uncommon etiology of ICD dysfunction. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8(3):582–3.

Bellinge JW, Petrov GP, Taggu W. Reel syndrome, a diagnostic conundrum: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021;5(10):ytab394.

Haslam M, Parkman HP, Petrov RV. Absorbable antibacterial envelope in the surgical management of Twiddler’s syndrome in a patient with gastric electric stimulator: a case report. Dig Med Res. 2020;3:76.

Shao J, Frizon L, Machado AG, McKee K, Bethoux F, Hartman J, et al. Occlusion of the Ascenda Catheter in a Patient with Pump Twiddler’s Sydrome: A Case Report. Anesth Pain Med. 2018;8(2):e65312.

Mohrsen SA. Vagus nerve stimulation: a pre-hospital case report. Br Paramed J. 2020;5(2):34–7.

Golovlev AV, Hillegass MG. New Onset Tinnitus after High-Frequency Spinal Cord Stimulator Implantation. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2019;2019:5039646.

Zoorob D, Deis AS, Lindsay K. Refractory Sexual Arousal Subsequent to Sacral Neuromodulation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2(2019):7519164.

Sharma P, Yassin M. Invasive Listeriosis of Intracardiac Device. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:1309037.

Kornberger A, Walter V, Jaeger F, Lehnert T, Soriano M, Moritz A, et al. Necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis and ventricular assist device infection: case report and review of literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2015;17(5):737–43.

Robledo-Nolasco R, González-Barrera LG, Díaz-Davalos J, León-Larios GD, Morales-Cruz M, Ramírez-Cedillo D. Allergic reaction to pacemaker compounds: Case reports. HeartRhythm Case Reports. 2022;8(6):410–4.

Xu J, Watts TE, Tobler G, Paydak H. Graft-versus-host disease: A rare complication of device implantation. HeartRhythm Case Reports. 2016;2(5):446–7.

Durkin M, O’Brien N, Ghafur S. Cybersecurity in health is an urgent patient safety concern: We can learn from existing patient safety improvement strategies to address it. J Patient Safety Risk Manage. 2021.

Warner L, Branstad A, Hunter Guevara L, Matzke Bitterman L, Pingree M, Nicholson W, et al. Malfunctioning sufentanil intrathecal pain pump: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2020;3(14):1.

Singh S, Bora GS, Devana SS, Mavuduru RS, Singh SK, Mandal AK. Instrument malfunction during robotic surgery: A case report. Indian J Urol. 2016;32(2):159–60.

Shao W. Cochlear implant electrode failure secondary to silicone touch-up during device manufacturing. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(7):e72–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e318298aaaf. (PMID: 23921929).

Kimura KS, Patel SA, Freeman MH, Rivas A. New-onset seizures following cochlear implantation reprogramming – A case report. Otolaryngology Case Reports. 2015.

Patel S, Das S, Stedman RB. Urgent cesarean section in a patient with a spinal cord stimulator: implications for surgery and anesthesia. Ochsner J. 2014;14(1):131–4.

Tang JE, Hyman JB. Syncope after administration of epidural analgesia in an obstetric patient with a vagus nerve stimulator. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;38:134–7.

van Bennekom MJ, de Koning PP, Denys D. Social media and smartphone technology in the symptomatology of OCD. Case Reports. 2018;2018:bcr.

Körmendi A, Brutóczki Z, Végh BP, Székely R. Smartphone use can be addictive? A case report. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(3):548–52.

Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Phenomenological analysis of maladaptive daydreaming associated with internet gaming addiction: a case report. Gen Psychiatr. 2021;34(2):e100419.

Sharp J, Miller H, Al-Attar N. Unforeseen challenges of living with an LVAD. Heart Lung. 2018;47(6):562–4.

Al-Shaiji TF, Malallah MA, Yaiesh SM, Al-Terki AE, Hassouna MM. Does Psychological Disturbance Predict Explantation in Successful Pelvic Neuromodulation Treatment for Bladder Dysfunction? A Short Series. Neuromodulation. 2018;21(8):805–8.

Dalex M, Malezieux A, Parent T, Zekry D, Serratrice C. Phrenic nerve stimulation, a rare complication of pacemaker: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(11):e25060.

Jumper N, Radotra I, Witt P, Campbell NG, Mishra A. Brachial plexus impingement secondary to implantable cardioverter defibrillator: A case report. Arch Plast Surg. 2019;46(6):594–8.

Sommer M, Stiksrud EM, von Eckardstein K, Rohde V, Paulus W. When battery exhaustion lets the lame walk: a case report on the importance of long-term stimulator monitoring in deep brain stimulation. BMC Neurol. 2015;19(15):113.

Hardell L, Carlberg M, Hedendahl LK. Radiofrequency radiation from nearby base stations gives high levels in an apartment in Stockholm, Sweden: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(5):7871–83.

Das S, Siroky GP, Lee S, Mehta D, Suri R. Cybersecurity: The need for data and patient safety with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18(3):473–81.

Katsaras D, Cassidy C, Lakha M, Gordon D, Goode G, Abozguia K. Intermittent Loss of Telemetry Data. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3(1):146–9.

Tanczer LM, López-Neira I, Parkin S. ‘I feel like we’re really behind the game’: perspectives of the United Kingdom’s intimate partner violence support sector on the rise of technology-facilitated abuse. J Gender-Based Viol. 2021;5(3):431–50.

Straw I, Tanczer L. Safeguarding patients from technology-facilitated abuse in clinical settings: A narrative review. PLOS Digital Health. 2023;2(1):e0000089.

Straw I, Tanczer L. 325 Digital Technologies and Emerging Harms: Identifying the Risks of Technology-Facilitated Abuse on Young People in Clinical Settings. Arch Dis Childhood. 2023;108(Suppl 2):54. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2023-rcpch.91. (adc.bmj.com).

Taylor DJ. Sexy But Psycho: How the Patriarchy Uses Women’s Trauma Against Them. UK: Hachette; 2022. p. 351.

Khan HR, Chan WK, Kanawati J, Yee R. A case report of inappropriate inhibition of ventricular pacing due to a unique pacemaker electrogram storage feature. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021;5(3):ytab096. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytab096.

Duncker D, König T, Müller-Leisse J, Michalski R, Oswald H, Schmitto JD, et al. Electric smog: telemetry interference between ICD and LVAD. Herzschr Elektrophys. 2017;28(3):257–9.

Roberto ES, Aung TT, Hassan A, Wase A. Electromagnetic Interference from Swimming Pool Generator Current Causing Inappropriate ICD Discharges. Case Rep Cardiol. 2017;2017:6714307.

Knight HM, Cakebread HE, Gajendragadkar PR, Duehmke RM. Sleeping with the fishes: Electromagnetic interference causing an inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock. BMJ Case Reports. 2014.

Najjar E, Hallberg Kristensen A, Thorvaldsen T, Dalén M, Jorde UP, Lund LH. Electrostatic Discharge Causing Pump Shutdown in HeartMate 3. JACC Case Reports. 2021;3(3):459–63.

Erqou S, Kormos RL, Wang NC, McNamara DM, Bazaz R. Electromagnetic Interference from Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD) Inhibiting the Pacing Function of an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) Device. Case Rep Cardiol. 2018;2018:6195045.

Plakke MJ, Maisonave Y, Daley SM. Radiofrequency Scanning for Retained Surgical Items Can Cause Electromagnetic Interference and Pacing Inhibition if an Asynchronous Pacing Mode Is Not Applied. A & A case reports. 2016;6(6):143–5.

Rath S, et al. Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) as a Cause of Facial Nerve Stimulation After Cochlear Implantation: A Case Report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022;131(9):1043–7.

Shenasa M, Heidary S, Shenasa H. Inappropriate ICD shock due to hot tub-induced external electrical interference. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51(5):852–5.

Babic MD, Tomovic M, Milosevic M, Djurdjevic B, Zugic V, Nikolic A. Inappropriate shock delivery as a result of electromagnetic interference originating from the faulty electrical installation. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022;27(5):e12952.

Asher EB, Panda N, Tran CT, Wu M. Smart wearable device accessories may interfere with implantable cardiac devices. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;7(3):167–9.

Wight J, Lloyd MS. Swimming pool saline chlorination units and implantable cardiac devices: A source for potentially fatal electromagnetic interference. HeartRhythm Case Reports. 2019;5(5):260–1.

Pardo JV. Adjunctive vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: managing device failure or the end of battery life. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015213949. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-213949.

Tami A, Gerges D, Herrington H. Stridor Related to Vagus Nerve Stimulator: A Case Report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):E1733–4.

The Royal College of Pathologists. Guidelines on autopsy practice: guidance for pathologists conducting post-mortem examinations on individuals with implanted medical devices. London; 2022. Available from: https://www.rcpath.org/uploads/assets/4f04f871-257e-446b-b94f38095defaf0d/guidance-for-pathologists-conducting-post-mortem-examinations-on-individuals-with-implanted-medical-devices.pdf. Accessed Jul 2023.

Hand KS, et al. ‘It Makes Life so Much Easier’-Experiences of Users of the MicroGuideTM Smartphone App for Improving Antibiotic Prescribing Behaviour in UK Hospitals: An Interview Study. JAC Antimicrobial Resistance. 2021;3(3):111.

Kazemian P, Xu L. First reported case of a longevity overestimation error in the new Medtronic tablet-based device programmer. J Arrhythmia. 2020;36(5):929–31.

Kavanagh KT, Brown RE, Kraman SS, Calderon LE, Kavanagh SP. Reporter’s occupation and source of adverse device event reports contained in the FDA’s MAUDE database. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;2(10):205–8.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

The research was supported by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI Grant Reference Number EP/S021612/1) who fund the doctoral research of the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IS conceived of the idea and developed the preliminary background research. PN and GR contributed to the ideas in the manuscript through group discussion and provided edits and reviews to the manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required or sought as this was a systematic review that didn’t involve human subjects.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table A.

Details of Systematic Literature Review.

Additional file 2.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Straw, I., Rees, G. & Nachev, P. 21st century medicine and emerging biotechnological syndromes: a cross-disciplinary systematic review of novel patient presentations in the age of technology. BMC Digit Health 1, 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00044-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00044-x