Abstract

Background

At least 163 countries use a form of home-based record, a document to record health information kept at home. These are predominantly paper-based, although some countries are digitalizing home-based records for improved access and use. This scoping review aimed to identify efforts already undertaken for the digitalization of home-based records for maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) and lessons learned moving forward, by mapping the available peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Methods

The scoping review was guided by Arskey and O’Malley’s framework. A literature search of references published from 2000 until 2021 was conducted in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, EBM reviews, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore as well as a grey literature search. Title and abstract and full texts were screened in Covidence. A final data extraction sheet was generated in Excel.

Results

The scoping review includes 107 references that cover 120 unique digital interventions. Most of the included references are peer-reviewed articles in English language published after 2015. Of the 120 unique digital interventions, 80 (66.7%) are used in 31 different countries and 40 (33.3%) are globally available pregnancy applications. Out of the 80 digitalization efforts from countries, most are concentrated in high-income countries (n=68, 85%). Maternal health (n=73; 61%) and child health (n=60; 50%) are the main health domains covered; the main users are pregnant women (n=57; 48%) and parents/caregivers (n=43; 36%).

Conclusions

Most digital home-based records for MNCH are centered in high-income countries and revolve around pregnancy applications or portals for home access to health records covering MNCH. Lessons learned indicate that the success of digital home-based records correlates with the usability of the intervention, digital literacy, language skills, ownership of required digital devices, and reliable electricity and internet access. The digitalization of home-based records needs to be considered together with digitizing patient health records.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A home-based record is a document used to record an individual’s history of health services received, and in some countries, also to share health education messages. Those who interact with the home-based record are typically the individual or their parent/caregiver, health workers, and those managing and monitoring public health programmes. Home-based records can have different formats. For maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) programmes, formats include immunization records, antenatal care records, child health booklets, or maternal and child health booklets [1]. The use of home-based records has been recommended for MNCH by the World Health Organization to compliment facility-based records to improve care-seeking behavior, men’s involvement, maternal and child self-care, family care practices, infant and child feeding, and communication between health workers and women/parents [2].

At least 163 countries use some form of home-based records, with the highest prevalence of home-based records (90%) in the European Region [2,3,4]. However, these records vary greatly in terms of their design and information captured. They are adapted for use in local contexts, by considering health priorities, available services, and languages. Furthermore, the content, design, and durability of home-based records are crucial for their sustainability, effectiveness and implementation [5]. The great majority of these home-based records are paper-based, although many countries have plans for digitalizing them for improved access to key health information and use, as well as for higher rates of recording of health information [4]. In some middle- and high-income countries, electronic home-based records are already used to promote information sharing between providers, to improve the integration of care, and to reduce the risk of data loss [6]. However, in many countries electronic health management information systems remain in their infancy and paper home-based record will remain important as these systems mature [7].

To learn from the literature and experiences prior to planning new activities, global partners supporting the implementation and monitoring of home-based records have identified the digitalization of home-based records as an important area for future work and proposed to conduct a scoping review. A scoping review aims to map key concepts underpinning a research area and to identify the main sources and types of evidence available [8].

This objective of the scoping review was to understand the efforts already undertaken in terms of the digitalization of home-based records for MNCH and to compile the lessons learned for moving forward by mapping peer-reviewed and grey literature. The following review question guided the exercise towards this objective:

-

What efforts have already been undertaken for the digitalization of home-based records for MNCH?

Moreover, the following six sub-questions were to be answered:

-

1.

In which geographical contexts have efforts to digitalize home-based records already been undertaken?

-

2.

What are the experiences in the public versus the private sectors for these efforts?

-

3.

What studies or evaluations affiliated with these digital interventions are known?

-

4.

What are the challenges and lessons learned from these efforts to digitalize and implement?

-

5.

What literature is available from health areas other than MNCH regarding digitalization of home-based records?

-

6.

What terminology is most commonly used in relation to digitalization of home-based records?

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review on this topic.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [8] that includes the following five steps: 1) development of the research question; 2) development of a search strategy to identify relevant materials; 3) application of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of relevant materials; 4) data extraction from the included materials and 5) synthesizing the findings. The objectives, eligibility criteria, and methodology of the conduct of this scoping review were previously documented in a protocol [9]. The results of the scoping review are reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [10] (see Supplementary file).

Data sources

The scoping review drew on a variety of different materials, including published and grey literature to ensure diversity in the retrieved materials. These were retrieved through four mechanisms: an electronic database search, a grey literature search, expert recommendations, and reference searching.

Based on the preliminary search strategy included in the protocol, flexibility was adopted to refine and narrow it down. In September 2021, a librarian conducted an electronic database search in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, EBM reviews, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore. Preprints were searched through ArXiv and a grey literature search conducted, as outlined in the Supplementary file. Experts in the field were contacted to provide relevant materials that might be missed through the database search. The bibliographies of included references and of systematic reviews that were identified through the search were also reviewed. An overview of the results by database is available the Supplementary file.

Search terms

Relevant search terms were defined in the methods guide, however the final terms were determined through an iterative process. Search terms were tested and refined based on the relevance of materials found with particular search terms. For example, using search terms like ‘vaccination’ and ‘immunization’ on their own resulted in a lot of irrelevant materials. Therefore, the search was narrowed by combining terms such as ‘vaccination’ or ‘immunization’ with terms such as ‘card’, ‘record’ or ‘passport’. A list with the final search terms used in the different databases can be found in the Supplementary file. The terms aimed to encompass a wide range of terms used to refer to ‘home-based records’ in various countries. A filter was applied to search for relevant terms in the titles and abstracts.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The references resulting from the search strategy were considered for inclusion based on predetermined criteria. In order to ensure that the criteria were sensitive in capturing relevant materials, they were tested on a sample of studies identified during preliminary searches. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used can be found in Table 1.

Due the focus of this scoping review on digital interventions that included an individual’s access to a health record, there were several MNCH-related digital interventions that were removed, because they did not fulfill all inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, there are several pregnancy applications providing information, but without health record access. Similarly, portals or applications meant to provide vaccine information and promote uptake, but without access to the vaccination record, were not included. Digital interventions entailing one-directional text messages, such as appointment reminders, or a physical token, such as a near-field communication token, with a digital copy of a health record that cannot be accessed by the patients themselves, were also excluded.

Reference screening and selection

All references identified through the search strategy were uploaded into Covidence [11], where duplicates were removed. The screening was done by authors MG and NG independently, after a common understanding was established based on test screening of a few references. MG completed the screening of all references at title and abstract and full-text stage, and NG independently screened a random sample of 20% for quality assurance at both stages. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with AP. Materials not in English were assessed with the help of Google Translate or using language skills from the review team. A reference identified in German was reviewed by NG. This scoping review encompassed literature focusing on MNCH. Literature that addressed digital home-based records in other health areas were noted but considered beyond the scope of this review.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed in Covidence through an iterative process, tested against five included references to ensure all necessary data was captured appropriately and best met the objectives of the scoping review. The final version of the data extraction form can be found in the Supplementary file. Data extraction was done in Covidence. MG extracted information from all references, and NG reviewed a 50% sample. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion among MG and NG and, if consensus was not reached, managed by AP. The extracted information was imported from Covidence to a Microsoft Excel (Excel version 16.64, https://office.microsoft.com/excel, 2022, Redmond, United States of America (USA)) spreadsheet and was finalized in Excel.

The first columns in the data extraction sheet related to the included references, for example publication type, timeline, language. Other information that was extracted referred to the digital interventions identified through the references, for example geographical area, health domain, implementers, funders and scale of implementation (see Supplementary file).

Moreover, a free text column captured any reflections in the included manuscripts related to factors influencing the implementation of the digital interventions, which were then grouped together in similar categories. The result section is divided accordingly and first presents findings related to the included references, while the latter section refers to the digital interventions identified.

If a digital intervention covered more than one health domain (maternal health, newborn health, child health, immunization), all health domains were marked in the data extraction sheet. Subcategories for each health domain were also coded (for example, antenatal care, postnatal care, immunization, nutrition, growth and development). If a digital intervention did not mention explicit reference to a particular health domain, for example because it was created for the general population and included MNCH, maternal, newborn, and/or child health were all indicated in the data extraction sheet.

Results

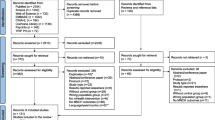

The different searching techniques retrieved a total of 630 records that were uploaded in Covidence. Figure 1 describes the reference selection process. After 11 duplicates were excluded, 617 records were screened on title and abstract. A further 324 records, including an additional 28 duplicates, were excluded. The full texts of 295 records were screened, with 107 references meeting the criteria for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion at full-text stage can be reviewed in Figure 1.

Some references covered more than one digital intervention. Conversely, several references focused on the same digital intervention. The 107 included references covered 120 unique digital interventions. A list of all included references can be found in the Supplementary file.

The findings are divided in two parts: the first section presents the characteristics of the 107 included references, such as publication type, timeline and language. The second part describes the characteristics of the 120 unique digital interventions, including geographical distribution, health domains and targeted users, implementers, funders, scale of implementation, terminology for digital interventions, associated studies, aim of the digital interventions, and reflections on the impact of digital interventions. The latter section responds to the main review question: What efforts have already been undertaken for the digitalization of home-based records for MNCH? A summary table with the characteristics is provided in the Supplementary file.

Characteristics of included references

Publication type, timeline, language

Of the 107 references, the majority were peer-reviewed articles (n=76; 71%) or other types of academic publications (n=17; 16%; i.e. conference papers and posters, and master theses). Only a small number of the included publications were other type of publications (n=14; 13%; i.e. NGO reports, government documents). The majority (n=76; 71%) of included references were published since 2015 (Figure 2).

All included materials were in English language, apart from one German reference. The geographic scope of the 107 references was characterized by an Anglophone dominance.

Characteristics of the digital interventions

Geographical distribution

Out of the 120 digital interventions, 80 (66.6%) were used in 31 countries, compared to 40 (33.3%) pregnancy applications that could be used globally. The majority of interventions (n=38; 31.7%) focused on English-speaking countries: USA (n=28), Canada (n=4), United Kingdom (n=3), Australia (n=2), and Ireland (n=1), as indicated in Table 2.

Based on the income levels by the World Bank [12], out of the 80 digitalization efforts from countries, most were concentrated in high-income countries (n=68, 85%). A significantly smaller proportion were from upper-middle income countries (n=9; 11%) and few from lower-middle income countries (n=3; 4%). None of the digital interventions was implemented in low-income countries.

Health domains and targeted users

Maternal health (n=73; 61%) was the main health domain covered across the 120 unique digital interventions, due to a large number of pregnancy applications that were identified, followed by child health (n=60; 50%) and newborn health (n=40; 33%) (Figure 3). Several of the digital interventions covered more than one health domain (for example, newborn and child health). Few (n=3; 2.5%) digital home-based records covered immunization for the general population (i.e. CANImmunize in Canada).

For slightly more than two-third (n=82; 68%) of digital home-based records, the health domains could be further specified. Out of these 82 records, the majority recorded data on pregnancy (n=56; 68%), immunization (n=23, 28%) and growth and development (n=17; 21%). Information about postnatal care was captured in two digital home-based records and another two captured data on nutrition. A total of 17 (21%) digital interventions covered more than one subcategory of health domains.

Overall, the main user groups targeted by the 120 digital interventions were pregnant women (n=57; 48%) and parents/caregivers (n=43; 36%). In some cases (n=20; 17%), digital interventions were designed for the general population, or the patient population at a specific hospital, which implicitly encompasses MNCH user groups such as parents and pregnant women.

Implementers, funders, and scale of implementation

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of implementers of the digital interventions, predominantly by government (n=20; 17%), university health facilities (n=10; 8%) and health institutions (n=9; 7%). For more than half of the interventions, the implementer was not clear, not specified in the report or difficult to discern (i.e. for pregnancy apps) (n=66, 55%). Out of the 120 digital interventions, the majority (n=110; 92%) were associated with a study, while the remaining 10 (8%) were not.

In many cases the funding source for the digital intervention was also not clearly stated. However, for some national digital interventions, such as eRedbook in the UK, it was implicit that funding came from the national government. A third of the 120 digital interventions were implemented at global level (n=40; 33%), which includes pregnancy monitoring apps. Of the remaining 80 references, 16 (13%) digital interventions were implemented at national level, e.g. the eRedbook in the UK or CANImmunize in Canada. Many of the other interventions were either implemented at individual health facilities (n=13; 11%) or were at the pilot stage (n=13; 11%) (Figure 5).

Terminology for digitalization interventions

The most common terminology for the 120 digital health interventions was ‘patient portal’ (n=26; 22%). Other terminology included ‘Personal Health Record’ (PHR) (n=17; 14%), including ‘personal child health record’ and ‘mobile Personal Health Record’, which typically provide patient access to the patient information captured in an electronic health record (EHR), often through a patient portal. Definitions for patient portal, PHR, and vaccination app are provided in Table 3.

The term ‘Electronic/Digital Health Record’ was commonly used in relation to the digital interventions (n=19; 16%), even though it is not strictly an example of a digitalized home-based record, as it typically only provides access to healthcare providers and not to patients. However, it is directly intertwined with PHRs that are typically built as an extension of existing EHRs that healthcare providers already use to access the patient health records, by giving the patient also access to their health record that is already available in the EHR.

Aim of the digitalization interventions

The aims of the digital interventions in the included references can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Individual patients and parents/caregivers given online access to their or their child’s health records or clinical notes.

-

2.

Individual patients and parents/caregivers actively engaging in their own healthcare or their child’s healthcare, including communications with health workers.

-

3.

Individual patients and parents/caregivers tracking and managing immunizations.

-

4.

Supporting women to monitor their pregnancy.

-

5.

Providing a digital versions of paper-based home-based records (e.g. parent-held record books, child health records/books).

Factors influencing the implementation of the digital interventions

The included references have a broad scope in terms of the impact of the digital interventions and possible barriers to implementation they discuss, which can be grouped under the following categories: 1) Usability and functionality; 2) User characteristics influencing the implementation of the digital intervention; 3) Confidentiality, security and credibility; 4) Further impact of the digital interventions (Table 4).

Usability and functionalities

Design and usability factors influence the successful uptake of digital home-based records. For example, the design simplicity, content, and user-friendly user interfaces are determinants of how likely a system will be used. One study identified how difficulties in navigation and the complexity of the medical language reduced user motivation [27]. Another publication outlined how pregnant women preferred the paper-based version as the digital system was unfamiliar and difficult to navigate [28]. Moreover, proper orientation on digital interventions, what it is, what services are offered and how to use it are important enablers.

The different digital interventions cover a range of functionalities ranging from appointment reminders to discussion forums to electronic prescriptions. One of the more popular features is access to diagnostic results, although there are calls for updates to be quicker [27, 29, 30]. Provider-patient communications can be improved through electronic systems [31]. Moreover, users need to be encouraged to report concerns or errors [32]. Frequent power interruptions can pose a challenge for digitalization and for operations and maintenance in resource-constrained settings [25].

User characteristics influencing the implementation of the digital interventions

There are a number of user characteristics that determine the potential for successful use of digital home-based records. These indicate that in the end the successful adoption of a system depends on a combination of people’s skills and resources, technology, and processes [31, 33,34,35,36,37], namely 1) digital literacy skills; 2) ownership of digital devices, 3) reliable electricity and internet access, and 4) language skills in the operational language of the digital intervention.

The presence or absence of these factors greatly varies with socioeconomic status with a risk that digitalization of home-based records can lead to further reinforcement of racial, ethnic, economic, and educational disparities [38]. For example, interventions that are only available for iPhone and not Android pose limitations for people of lower economic status [39]. Moreover, digital interventions should be sensitive to the diverse needs of the populations and bridge the rural/urban divide [40].

Confidentiality, security, and credibility

Confidentiality, security, and credibility of data are essential for the management of PHRs, including digital home-based records. Parents frequently express concerns about who has access to their own or their children’s health data [13, 20, 27, 41,42,43]. Yet, the benefits of being able to view medical records, get laboratory results, or send messages often outweigh confidentiality concerns.

Parental proxy access is often limited for adolescents and depends on the regulatory system within which the digital intervention operates. This possibly explains why adolescents were not as prevalent among the target users of the digital interventions in the included references. For example, in the USA, legal rights to access medical records by adolescents and parents varies between states and may differ depending on the record’s content, especially for psychiatric or reproductive health issues [27]. Confidentiality is typically handled at the facility level, but this becomes more complex with the availability of electronic data and calls for further research to meaningfully and securely communicate appropriate information with teenagers and guardians [44].

Examples of frequently mentioned digital interventions

Several digital interventions were covered in different references. For example, 19 references referred to a patient portal in the USA, ten discussed a PHR in the United Kingdom (UK), nine references discussed an application in Canada, three an application in Jordan, and two discussed a different application in Jordan.

CANImmunize (Canada) [33, 39, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51] https://www.canimmunize.ca

The CANImmunize application was launched in 2014 as ImmunizeCA. It was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and developed by researchers at the Ottawa Hospital to help Canadians store, manage, and access immunization information. CANImmunize is a free bilingual (English and French) application that allows individuals to manage their own and their family's vaccination records. It does not require users to be connected to WiFi and allows Canadian residents to easily access their records anytime, anywhere. The application permits multi-record vaccination tracking for parents or guardians to view digital records for themselves or their dependents. Information on vaccination in each jurisdiction is easy to understand and there are reminders for upcoming or overdue vaccinations.

MyChart (USA) [22, 29, 31, 44, 52,53,54,55] https://www.mychart.com/

MyChart is a patient portal with a secure website for patients to access personal health information. It is a real-time, patient-centered record with information available instantly wherever and whenever needed. MyChart patients are able to view records, clinical notes, laboratory, and imaging results. It also allows for messages, scheduling of appointments, and requests for medication refills. Patients have the option to sign up for patient portal access, but it is not required. Parents and legal guardians can obtain proxy access to their child’s patient portal account in an unrestricted manner through to age 11, whereas for adolescents 12–17-years, the proxy access by parents and guardians is restricted.

eRedbook (UK) [34, 56,57,58,59,60,61] https://www.eredbook.org.uk/

The eRedbook is the UK's first digital PCHR that has been available nationwide since 2020. The online version of the familiar parent-held record book/’red book’ facilitates a move from paper to electronic records, although parents will still be able to choose between paper or electronic. The eRedbook stores information about immunizations, health reviews, and screening tests; it tracks weight and height to give age-appropriate guidance. It was created and is maintained by parents and health professionals to involve parents in managing their child's health with an array of tools. The eRedbook can be accessed by parents with an internet connection through a computer, tablet or smartphone.

eMCH Handbook (Jordan) [28, 62, 63]

In April 2017, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) released an electronic Maternal and Child Health Handbook (e-MCH Handbook) specifically for a refugee setting in Jordan. The application gives pregnant women and mothers on- and offline access to educational information and to both their own and their children’s PHRs on a smartphone and is one of the first mobile health interventions in a refugee setting. The e-MCH Handbook also sends reminders for appointments and health education information. The e-MCH Handbook also functions as an efficient communication tool between patients and UNRWA health centres compared to the paper-based MCH Handbook.

Children Immunization App (Jordan) [64, 65]

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.letsnurture.vaccination&hl=en_US&gl=US

The Children Immunization App (CImA) is a vaccination application for refugee settings that has been implemented in Zaatari Camp since 2019. The application is freely available in Google Playstore, in both English and Arabic (Android only). It documents the vaccination history of Syrian children and includes health education information and automated reminders for parents. There is a visual tool for parents with limited literacy.

Discussion

This section responds to the different questions the scoping review set out to answer, based on the results.

What efforts have already been undertaken for the digitalization of home-based records for MNCH?

The identified digital interventions were mostly applications to monitor pregnancies, revolved around general patient portals to give access to patient health records or specific MNCH-related interventions focused on either immunization or maternal and child health records (e.g. eRedbook in UK and CANImmunize in Canada).

In which geographical contexts have efforts to digitalize home-based records already been undertaken?

Overall, the scoping review demonstrated that the efforts for digitalization of home-based records for MNCH are centered in high-income countries, particularly the USA and other Anglophone countries. The findings indicate digital interventions exist in high- and middle-income countries, though there is a clear gap in the available literature on digitalization of home-based records in low-income countries.

Digital home-based records may be more prevalent in high-income countries, as digital devices, reliable electricity and internet access, digital literacy, and financial resources for internet access are more readily available than in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, the necessary financial resources and skills to undertake the digitalization of home-based records are often more readily available in high-income countries.

What are the experiences in the public versus the private sectors for these efforts?

The majority of digital interventions were implemented through initiatives of national governments, by university or private health facilities. Other stakeholders like NGOs, telecommunication companies or private companies only appeared minimally in the included references. It is well possible that the digital interventions at particular health facilities were also used in other parts of the country or even in other countries, even if this was not directly evident in the particular publication. For a substantial number of digital interventions, particularly the pregnancy monitoring apps, it was unclear, who the implementer was.

What terminology is most commonly used in relation to digitalization of home-based records?

The most prevalent terminology for digital interventions across the included references were ‘(online) patient portal’ (22%) and ‘Personal Health Record’ (14%). Both refer to a form of online access to a health record and this gives a clear indication that the most common access to home-based records for the included digital interventions is through an online patient portal. Online patient portals are typically not MNCH-specific, but rather for the general population, with specific access for parents and caregivers to their children’s records. Because the search strategy was tailored towards MNCH, the online patient portals identified were usually part of a maternal or pediatric study.

What are the challenges and lessons learned from these efforts to digitalize and implement?

Given the broad diversity of digital interventions covered by the included references, there are a range of challenges and lessons learned from the references that can inform future digitalization of home-based records, particularly for underserved populations and remote geographical areas. There are many factors that influence the impact of any digital interventions and can pose barriers to implementation (see Table 5). Efforts should be made to ensure that already vulnerable populations are not further disadvantaged through the digitalization of home-based records.

Limitations

Despite the strength of scoping reviews in mapping available evidence, there are inherent limitations to its methodology that are important to note. The search strategy primarily targeted results that made explicit reference to MNCH-related search terms in the title or abstract, which means that any relevant digital interventions where MNCH search terms did not appear explicitly might have been missed. Moreover, some search terms were narrowed (e.g. ‘vaccination record’ instead of ‘vaccination’) in order to reduce the number of irrelevant results. While some relevant literature may have been missed, this limitation was balanced against the feasibility of reviewing such a large body of references with the potential for a low yield.

A particular challenge for this review was the wide range of terms used to refer to ‘home-based records’ in various countries, ranging from ‘vaccination passport’ to ‘under-fives cards [66, 67]. The search strategy sought to encompass all these terms but may have missed relevant ones. As the search strategy was primarily based on English search terms, it resulted in predominantly Anglophone publications, even though no language filter was applied. A preliminary search revealed a number of examples of home-based records in local vernaculars in non-English speaking countries that were not easily picked up by the search strategy due to the lack of documentation in English, for example the electronic health-care service portal Elektronikus Egészségügyi Szolgáltatási Tér in Hungary.

Finally this search focused on MNCH literature. Additional insights and lessons learnt may be drawn from other health areas, which was considered beyond the scope of this review.

Despite these limitations, the authors are confident that the search strategy has nevertheless captured the majority of the available relevant literature, as reflected by the 107 references included for data extraction.

Conclusion

This scoping review mapped the available evidence from peer-reviewed and grey literature available on the digitalization of home-based records for MNCH. It demonstrated that digital home-based records exist, particularly in high-income countries, though increased efforts are needed to document and share promising experiences for other countries to learn from.

As the digitalization of home-based records cannot be considered separately from the digitalization of the health information system and electronic health records more generally, future efforts could establish a better link between digital home-based records and the development of electronic health records that allow patients to access their records. Likewise, future work could investigate non-MNCH specific literature to determine whether broader lessons of digital home-based records outside the MNCH domain are available.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brown DW, Gacic-Dobo M, Young S. Home-based vaccination records — a reflection on form. Vaccine. 2014;32(16):1775–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.098.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations on home-based records for maternal, newborn and child health. Geneva: WHO; 2018. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/home-based-records-guidelines/en/.

Brown DW, Gacic-Dobo M. Home-based record prevalence among children aged 12–23 months from 180 demographic and health surveys. Vaccine. 2015;33(22):2584–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.101.

World Health Organization (WHO). Use of home-based records for children in the countries of the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO; 2020. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/child-and-adolescent-health/publications/2020/use-of-home-based-records-for-children-in-the-countries-of-the-who-european-region-2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Practical guide for the design, use and promotion of home-based records in immunization. Geneva: WHO; 2015. https://www.who.int/immunization/documents/monitoring/who_ivb_15.05/en/.

Magwood O, Kpadé V, Afza R, Oraka C, McWhirter J, Oliver S. Understanding women’s, caregivers’, and providers’ experiences with home-based records: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204966.

Brown DW. Is there a place for home-based records alongside electronic health records and/or electronic registries? 2018. https://www.technet-21.org/fr/forums/discussions/is-there-a-place-for-home-based-records-alongside-electronic-health-records-and-or-electronic-registries. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping Studies Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Geldof M, Gerlach N, Lochlann, LN, Sauvé, Portela, AG. Digitalization of home-based records for maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH): a scoping review protocol. Protocols.io website. https://www.protocols.io/view/digitalization-of-home-based-records-for-maternal-4r3l24znpg1y/v1. Accessed July 1, 2022.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Covidence. Melbourne, Australia. https://www.covidence.org. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

World Bank income classification previous years. Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/site-content/OGHIST.xls. Accessed May 22, 2023.

Miklin DJ, Vangara SS, Delamater AM, Goodman KW. Understanding of and Barriers to Electronic Health Record Patient Portal Access in a Culturally Diverse Pediatric Population. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(2):e11570. https://doi.org/10.2196/11570.

Sommer J, Daus M, Smith M, Luna D. Mobile application for pregnant women: what do mothers say? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:221–4.

Sommer J, Daus M, Simon M, Luna D. Health portals for specific populations: A design for pregnant women. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;250:3–6.

Thomas G. Building the foundations for better healthcare in Wales. Br J Healthcare Comput Inform Manag. 2006;23(6):9–12.

Seeber L, Conrad T, Hoppe C, Obermeier P, Chen X, Karsch K, Muehlhans S, Tief F, Boettcher S, Diedrich S, Schweiger B, Rath B. Educating parents about the vaccination status of their children: A user-centered mobile application. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:241–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.01.002.

Barbour KA, Nelson R, Esplin MS, Varner M, Clark EAS. 873: A randomized trial of prenatal care using telemedicine for low-risk pregnancies: patient-related cost and time savings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):S499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.782.

Kalejta CD, Higgins S, Kershberg H, Greenberg J, Alvarado M, Cooke K, Bhatt S, Bulpitt D, Armour J, Bejjani B, Ryan S, Elms A. Evaluation of an automated process for disclosure of negative noninvasive prenatal test results. J Genet Couns. 2019;28(4):847–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1127.

Bourgeois FC, Taylor PL, Emans SJ, Nigrin DJ, Mandl KD. Whose personal control? Creating private, personally controlled health records for pediatric and adolescent patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(6):737–43. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2865.

McArthur L. A quality improvement project for breastfeeding promotion via the patient portal. J Inform Nurs. 2020;5(4):13–21.

Kim J, Mathews H, Cortright LM, Zeng X, Newton E. Factors Affecting Patient Portal Use Among Low-Income Pregnant Women: Mixed-Methods Pilot Study. JMIR Form Res. 2018;2(1):e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/formative.5322.

Lyles CR, Allen JY, Poole D, Tieu L, Kanter MH, Garrido T. “I Want to Keep the Personal Relationship With My Doctor”: Understanding Barriers to Portal Use among African Americans and Latinos. J Med Int Res. 2016;18(10):e263. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5910.

Ginting K, Stolfi A, Wright J, Omoloja A. Patient Portal, Patient-Generated Images, and Medical Decision-Making in a Pediatric Ambulatory Setting. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(5):764–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718754.

Radhakrishna K, Goud BR, Kasthuri A, Waghmare A, Raj T. Electronic health records and information portability: a pilot study in a rural primary healthcare center in India. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2014;11(Summer):1b.

Gault G, Fischer A, Nicand E, Burelle F, Burbaud A, Koeck JL. Assessment of vaccination coverage of adolescents aged 16–18 years with an innovative electronic immunization record system. Med Mal Infect. 2019;49(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2018.11.001.

Britto MT, Jimison HB, Munafo JK, Wissman J, Rogers ML, Hersh W. Usability testing finds problems for novice users of pediatric portals. J Am Med Inform Assoc: JAMIA. 2009;16(5):660–9. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M3154.

Kitamura A, Goto R, Nasir S, Hababeh M, Bailout G, Seita A. UNRWA's electronic MCH Handbook application for Palestine Refugees. Technical Brief. 2018. https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/thematic_issues/health/c8h0vm0000f7kibw-att/technical_brief_mc_20.pdf. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Krasowski MD, Grieme CV, Cassady B, Dreyer NR, Wanat KA, Hightower M, Nepple KG. Variation in results release and patient portal access to diagnostic test results at an academic medical center. J Pathol Inform. 2017;8:45. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpi.jpi_53_17.

Kelly MM, Thurber AS, Coller RJ, Khan A, Dean SM, Smith W, Hoonakker P. Parent perceptions of real-time access to their hospitalized child’s medical records using an inpatient portal: a qualitative study. Hosp Paediatr. 2019;9(4):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0166.

Ukoha EP, Feinglass J, Yee LM. Disparities in electronic patient portal use in prenatal care: retrospective cohort study. J Med Intern Res. 2019;21(9):e14445. https://doi.org/10.2196/14445.

Lam BD, Bourgeois F, Dong ZJ, Bell SK. Speaking up about patient-perceived serious visit note errors: Patient and family experiences and recommendations. J Am Med Inform Assoc: JAMIA. 2021;28(4):685–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa293.

Paradis M, Atkinson KM, Hui C, Ponka D, Manuel DG, Day P, Murphy M, Rennicks White R, Wilson K. Immunization and technology among newcomers: A needs assessment survey for a vaccine-tracking app. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1660–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1445449.

O’Connor S, Devlin AM, McGee-Lennon M, Bouamrane MM, O’Donnell CA, Mair FS. Factors Affecting Participation in the eRedBook: A Personal Child Health Record. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;225:971–2.

Kitayama K, Stockwell MS, Vawdrey DK, Peña O, Catallozzi M. Parent perspectives on the design of a personal online pediatric immunization record. Clin Paediatr. 2014;53(3):238–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922813506608.

Arcia A. Time to push: use of gestational age in the electronic health record to support delivery of relevant prenatal education content. EGEMS (Washington, DC). 2017;5(2):5. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1281.

Deshpande S, Rigby M, Namazova-Baranova L. Use of home-based records for children in the countries of the WHO European Region. Geneva: WHO; 2020. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/446702/Use-of-home-based-records-for-children-in-the-countries-of-the-WHO-European-Region-eng.pdf. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Ukoha EP, Yee LM. Use of Electronic Patient Portals in Pregnancy: An Overview. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(3):335–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12761.

Wilson K, Atkinson K, Pluscauskas M, Bell C. A mobile-phone immunization record in Ontario: uptake and opportunities for improving public health. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20(8):476–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X14537771.

Singh H, Mallaiah R, Yadav G, Verma N, Sawhney A, Brahmachari SK. iCHRCloud: Web & Mobile based Child Health Imprints for Smart Healthcare. J Med Syst. 2017;42(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0866-5.

Bergman DA, Brown NL, Wilson S. Teen use of a patient portal: a qualitative study of parent and teen attitudes. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2008;5:13.

Halamka JD, Mandl KD, Tang PC. Early Experiences with personal health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2562.

Quinlivan JA, Lyons S, Petersen RW. Attitudes of pregnant women towards personally controlled electronic, hospital-held, and patient-held medical record systems: a survey study. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):810–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.0342.

Sarabu C, Lee T, Hogan A, Pageler N. The Value of OpenNotes for Pediatric Patients, Their Families and Impact on the Patient-Physician Relationship. Appl Clin Inform. 2021;12(1):76–81. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1721781.

Atkinson KM, Ducharme R, Westeinde J, Wilson SE, Deeks SL, Pascali D, Wilson K. Vaccination attitudes and mobile readiness: A survey of expectant and new mothers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(4):1039–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1009807.

Atkinson KM, Westeinde J, Hawken S, Ducharme R, Barnhardt K, Wilson K. Using mobile technologies for immunization: Predictors of uptake of a pan-Canadian immunization app (ImmunizeCA). Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20(7):351–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/20.7.351.

Atkinson KM, Westeinde J, Ducharme R, Wilson SE, Deeks SL, Crowcroft N, Hawken S, Wilson K. Can mobile technologies improve on-time vaccination? A study piloting maternal use of ImmunizeCA, a Pan-Canadian immunization app. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(10):2654–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1194146.

Bell C, Atkinson KM, Wilson K. Modernizing Immunization Practice Through the Use of Cloud Based Platforms. J Med Syst. 2017;41(4):57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0689-4.

Burgess K, Atkinson KM, Westeinde J, Crowcroft N, Deeks SL, Wilson K. Barriers and facilitators to the use of an immunization application: a qualitative study supplemented with Google Analytics data. J Public Health. 2017;39(3):e118–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw032.

Houle S, Atkinson K, Paradis M, Wilson K. CANImmunize: A digital tool to help patients manage their immunizations. Can Pharm J: CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada: RPC. 2017;150(4):236–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163517710959.

Wilson K, Atkinson KM, Penney G. Development and release of a national immunization app for Canada (ImmunizeCA). Vaccine. 2015;33(14):1629–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.022.

Bower JK, Bollinger CE, Foraker RE, Hood DB, Shoben AB, Lai AM. "Active Use of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and Personal Health Records (PHRs) for Epidemiologic Research: Sample Representativenessand Nonresponse Bias in a Study of Women During Pregnancy," eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes). 2017; 5(1): Article 1. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1263

Bush RA, Connelly CD, Pérez A, Chan N, Kuelbs C, Chiang GJ. Physician perception of the role of the patient portal in pediatric health. J Ambul Care Manag. 2017;40(3):238–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000175.

Szilagyi PG. Patient Portal - Flu Reminder Recall, clinical trial protocol. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2018. Accessed Sept 17, 2021. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03666026. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Szilagyi PG. Patient Portal Reminder/Recall for Influenza Vaccination in a Health System-UCLA Portal R/R Influenza RCT 3, clinical trial protocol. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2019. Accessed Sept 17, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04110314. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Online personal child health record to be evaluated. Community Pract. 2014;87(2):11.

eRedbook receives CPHVA endorsement. Community Pract. 2015;88(4):13.

Children’s “red books” start online roll-out. Community Pract. 2017;90(4):9.

Brown D. How are immunisation schedules affecting you? Practice Nursing. 2016;27(9):413. https://doi.org/10.12968/pnur.2016.27.9.413.

Gibson K. The eRedbook: Enabling digital transformation in health care. J Health Visit. 2016;4(1):27–30. https://doi.org/10.12968/johv.2016.4.1.27.

Moulin E. eRedbook. The UK’s electronic Personal Child Health Record. Presentation on eRedbook. https://www.wmhin.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/moulin_eRedbook_WIN2016.pdf. Accessed Sept 17, 2021.

Goto R, Nasir S, Kitamura A, Hababeh M, Ballout G, Kiriya J, Seita A, Jimba M. Dissemination and implementation of the e-MCH Handbook, the potential role of m-Health in improving health equity in a refugee setting: A cross-sectional study. USA: American Public Health Association Annual Meeting San Diego; 2018.

Nasir S, Goto R, Kitamura A, Alafeef S, Ballout G, Hababeh M, Kiriya J, Seita A, Jimba M. Dissemination and implementation of the e-MCHHandbook, UNRWA’s newly released maternal and child health mobile application: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e034885. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034885.

El-Khatib Z, El-Halabi S, Abu Khdeir M, Khader YS. Children Immunization App (CImA), Low-Cost Digital Solution for Supporting Syrian Refugees in Zaatari Camp in Jordan - General Description. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;271:117–20. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI200086.

Khader YS, Laflamme L, Schmid D, El-Halabi S, Abu Khdair M, Sengoelge M, Atkins S, Tahtamouni M, Derrough T, El-Khatib Z. Children Immunization App (CImA) Among Syrian Refugees in Zaatari Camp, Jordan: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial Intervention Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(10):e13557. https://doi.org/10.2196/13557.

World Health Organization (WHO). Ontology of home-based vaccination records. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Magwood O, Kpadé V, Thavorn K, Oliver S, Mayhew AD, Pottie K. Effectiveness of home-based records on maternal, newborn and child health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0209278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209278.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of: Caroline Sauvé, Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, who helped to develop and execute the search strategy; Laura Nic Lochlainn, World Health Organization Department of Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals; Anne Detjen, UNICEF, and Keiko Osaki, Ibi Tomomi and Hirotsugu Aiga from the Japan International Cooperation Agency for inputs on the methods guide. Finally, we thank Vanessa van Schoor from Integrity in Malawi for reviewing the final report.

Funding

This manuscript was developed with funding from the World Health Organization Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health and Ageing, through a grant received form the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marije Geldof: main author who prepared the scoping review protocol and undertook the search, screening and data extraction and led the writing of the manuscript. Nina Gerlach: second author who served as a second reviewer for the screening and data extraction and did substantial editing of the manuscript. Anayda Portela: Oversaw the scoping review, mediated any disagreements between the two reviewers and provided inputs into the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests. Anayda Portela is a staff member of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this manuscript and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the World Health Organization.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geldof, M., Gerlach, N. & Portela, A. Digitalization of home-based records for maternal, newborn, and child health: a scoping review. BMC Digit Health 1, 32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00032-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00032-1