Abstract

Eighty-one percent of persons living with cancer have an emergency department (ED) visit within the last 6 months of life. Many cancer patients in the ED are at an advanced stage with high symptom burden and complex needs, and over half is admitted to an inpatient setting. Innovative models of care have been developed to provide high quality, ambulatory, and home-based care to persons living with serious, life-limiting illness, such as advanced cancer. New care models can be divided into a number of categories based on either prognosis (e.g., greater than or less than 6 months), or level of care (e.g., lower versus higher intensity needs, such as intravenous pain/nausea medication or frequent monitoring), and goals of care (e.g., cancer-directed treatment versus symptom-focused care only). We performed a narrative review to (1) compare models of care for seriously ill cancer patients in the ED and (2) examine factors that may hasten or impede wider dissemination of these models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Within the last 6 months of life, 81% of persons living with cancer have an emergency department (ED) visit [1]. The majority of persons with cancer in the ED are at an advanced stage with high symptom burden and complex needs [2]. From the ED, over half is admitted to an inpatient setting, and they have high subsequent healthcare utilization and increased mortality in the month following their ED visit [3, 4]. For emergency clinicians, the path of least resistance for the care of these complicated patients is acute care admission. Hospitalization is not always the best solution however, as it comes with potential harms such as iatrogenic illness, deconditioning, and (during the pandemic) reduced visitation from loved ones and caregivers [5]. On the other hand, discharge home or to hospice requires significantly more planning and coordination of services from the ED team. Hospice coordination in particular can be difficult [6, 7].

Innovative models of care have been developed to provide high-quality, ambulatory, and home-based care to persons living with serious, life-limiting illness, such as advanced cancer. These include both face-to-face and telehealth-based visits and/or monitoring. While these programs are growing in number and reach, they are rarely known or accessible to emergency clinicians [8]. The growing integration and cross-training in emergency and hospice and palliative medicine are an opportunity to enhance collaboration between acute and supportive care services.

Multiple care models exist for seriously ill cancer patients, including inpatient and outpatient palliative care, telehealth and home-based palliative care (HBPC), home and inpatient hospice, and palliative care provided through integrated mobile technologies. These care models can be divided into categories based on level of care (e.g., lower versus higher intensity needs, such as intravenous pain/nausea medication or frequent monitoring), and goals of care (e.g., cancer-directed treatment versus symptom-focused care only). While use cases exist for all of these models, there are barriers specific to each model, therefore hindering widespread adoption. Barriers include the following: technical requirements, training required, reimbursement, evidence base, and patient or family burden (financial or otherwise) [9, 10]. For example, while discharge to home hospice can help avoid an admission in a patient with serious illness, the caregiving burden on family is substantial as compared to an inpatient stay [9]. While hospice requires patients to forgo disease-directed treatments and meet disease-specified prognostic guidelines, palliative care providers often see patients with similar prognoses that are still pursuing cancer-directed therapies [9]. Diagnostic uncertainty and difficulties with prognostic evaluation can be a barrier to hospice admission as well as patient/family reluctance to “give up” on cancer treatment [11] The median length of stay on hospice is 18 days, very late in the disease course, and 25% of patients on hospice lives < = 5 days [12].

We performed a narrative review to understand the evidence base for each of these models of care, as well as factors that may hasten or impede wider dissemination.

Methods

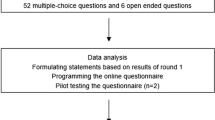

United States (US)-based physician content experts board certified in emergency medicine and/or hospice and palliative medicine each reviewed the literature on their respective care model. They all practice in academic medical centers and have between 5 and 28 years of clinical experience. The content experts convened first via videoconference to develop a consensus-based approach in defining models of care in advanced cancer patients who visit the ED. The list of models was confirmed, and then, relevant literature on each model was reviewed between March 10, 2022 and April 18, 2022. Each expert curated their literature review on each model of care based on the following themes: evidence base, benefits and barriers, care intensity, reimbursement, healthcare team composition, technical requirements, and patient/family burden. PubMed was the primary search engine tool. If no information was found in the academic literature, other reputable sources were used (e.g., governmental, organizational websites). Search terms all included emergency department and advanced cancer in addition to the model of care (e.g., inpatient palliative care, home-based palliative care). Two content experts performed each literature search to ensure all the appropriate references were captured for each care model. The Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) was completed [13].

Models of Care

Inpatient palliative care

Description and team composition

Of all the varied methods of palliative care delivery, inpatient consult service is the most established with strong evidence for efficacy and cost savings [14]. In 2019, 72% of hospitals with 50 or more beds had a palliative care team, up from 67% in 2015, 53% in 2008, and 7% in 2001 [15]. The makeup of inpatient palliative care teams varies widely across hospitals in the USA but can include clinicians, nurses, social workers (SW), chaplains, and pharmacists [16].

Benefits

Studies of the integration of oncology and palliative care show improved survival and symptom control, less anxiety and depression, reduced use of futile chemotherapy at the end of life, better family satisfaction and quality of life, and improved use of healthcare resources [17,18,19,20]. Studies have shown reduced costs for cancer patients receiving inpatient palliative care [21]. Utilization of inpatient palliative care consults increased for patients with primary brain malignancies from 2.3% in 2007 to 11.3% in 2016, indicating a substantial increase but still far below the number of patients who could benefit from services to manage symptoms and improve quality of life [22]. Studies have shown that oncology readmission rates can be reduced by palliative care consultation, mainly due to discharge to hospice [23]. Palliative care consultation triggered by the emergency department has been shown to improve quality of life [24].

Barriers

Most patients are referred to inpatient palliative care very late in their illness course, often within the final weeks of life [25]. Earlier involvement of inpatient palliative care would improve care quality at the end of life [26]. One perceived barrier is that patients and families’ negatively view palliative care, equating it with death and hopelessness; this can be overcome with improved explanation by oncologists and other non-palliative care clinicians [27].

Outpatient palliative care

Description and team composition

Outpatient palliative care is delivered in a variety of clinical settings including embedded within oncology clinics (in the same physical location), as well as in standalone clinics [28,29,30]. Currently, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare the different clinic models. However, existing studies suggested that embedded clinics had earlier referrals and greater frequency of visits [29]. Many experts feel embedded models increase collaboration with oncologists and improve convenience for the patients [31].

In addition to differences in physical location, the composition of outpatient palliative teams varies and may include a single physician or an interdisciplinary team (IDT) of advanced practice clinicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and/or chaplains [29]. The gold standard includes an interdisciplinary team; however, this is not feasible in some institutions. Longitudinal visits with outpatient palliative care along the course of illness allow for opportunities for rapport building, advance care planning, counseling and education, optimization of symptoms, and crisis prevention [29, 31]. Initial encounters typically last about an hour, and subsequent visits are most commonly conducted monthly [32].

Benefits

Outpatient palliative care has been the gold standard for early palliative care involvement in patients with advanced cancer since the landmark trial by Temel et al. in 2010. In this study, patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer were randomized to receive early palliative care within 8 weeks of diagnosis integrated with standard oncologic care versus standard oncologic care alone. Compare to those receiving standard care alone, patients receiving early palliative care had improved quality of life, less depression, and a 3-month survival advantage [19]. Following this study in 2012, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommended that palliative care be integrated into oncology services early in the disease course and concurrently with other life-prolonging therapies [33]. Subsequently, multiple studies have confirmed the benefits of outpatient palliative care showing decreased depression [34] and improved quality of life [18, 34,35,36], symptom burden [35,36,37], satisfaction with care [37,38,39,40], communication about end-of-life care preferences [34], survival [35, 36, 41], and healthcare utilization [37, 42].

Barriers

Despite the benefits, multiple studies indicate that palliative care access remains limited and delayed even in highly resourced institutions [43]. A survey of cancer centers published in 2020 showed that National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated cancer centers have improved access to outpatient palliative care with 95% now having outpatient palliative care; however, only 40% of non-NCI designated centers had access to outpatient palliative care [44]. Moreover, a study in California showed that outpatient palliative care capacity for oncology patients was only 24% of the estimated need [31]. Despite access being limited, the growing body of literature that demonstrates improved outcomes has led to a robust growth of outpatient palliative care over the last decade [29, 44]. Additional barriers include leaving home and travel to clinic and cost of co-payment. Reimbursement for outpatient palliative care is established and mirrors similar outpatient specialties, such as standard outpatient billing codes in a fee-for-service model of reimbursement [10].

Telehealth-based palliative care

Description and team composition

Telehealth has been defined by the US Health Resources and Service Administration as “the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration” [45]. Due to provider shortages and the challenges inherent in patients with serious illness traveling to clinic visits, traditional models of outpatient and home-based hospice and palliative care, where specially trained physicians, advanced practices providers, and other interdisciplinary team (IDT) members provide office-based care, are increasingly unable to meet the needs of the growing number of older adults with serious, life-limiting illnesses, such as cancer [46, 47]. Telehealth may augment and extend traditional clinic visits utilizing remote symptom monitoring of patients and caregivers using cellphone applications and virtual visits by clinicians [48, 49].

Benefits

For palliative patients with high symptom burden and poor functional status, decreasing the burden of travel to clinic has real benefit. For common cancer symptoms such as pain, anxiety, depression, and fatigue, the telehealth model is an effective way to monitor and treat them [50]. Telephonic augmentation can improve both symptom management as well as promote earlier hospice referrals [51]. Nurse-led telephonic programs and tele-palliative care models are in early stages of development but have the potential to widen the ability of palliative care to provide flexible, patient-centered care to patients with advanced cancer [52]. Two reviews of telephonic models in cancer care have shown benefit in symptom management in cancer, particularly related to anxiety, mental and emotional health, and fatigue [53,54,55]. The PRO-TECT randomized trial enrolled 1191 patients to either weekly internet or automated telephone surveys regarding symptoms which triggered automatic alerts to their oncology providers. Three-month follow-up surveys showed an improvement in physician function, symptom control and quality of life in the survey group [56].

Barriers

The main barrier inherent to nurse-led telephonic care is the inability of nurses to prescribe medications. This requires a telephonic, nurse-led program to actively engage with primary care clinicians and specialists which can be challenging, particularly if the nurse and provider do not work within the same health system. Programs may also struggle with coordinating care with primary providers and specialists [57, 58]. Additionally, patient identification, structure, and operational aspects of these programs have not been well described, making program replication challenging. One study of a nurse-led telephonic program for patients with lung cancer at any stage in the Veterans Affairs system did not show benefit, calling into question which patients may benefit from early access to services [59]. A large Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI) funded trial is currently underway to answer these questions as it compares nurse-led telephonic care to traditional clinic-based palliative care for patients with serious illness randomized after an ED visit [52]. Reimbursement is undeveloped, although some programs have been funded by insurers and/or health systems, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provided reimbursement for virtual physician telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic [59].

Home-based palliative care

Description and team composition

Due to increasing number of homebound adults, more attention has been paid to home-based palliative care (HBPC). In 2011, a study found that about two million US adults are homebound, and another 4.6 million are semi-homebound [60]. The 1-year mortality rate for homebound patients is 40% while 20% for semi-homebound, compared to 6% for non-homebound [61]. HBPC programs vary greatly in composition and can include nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, physicians, chaplains, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, and health aides [62]. They are typically lower touch than hospice programs, offering perhaps a monthly in-person visit supplemented by telephonic or telehealth care compared to weekly visits at minimum for patients on hospice. The early adopters of this model of care have typically been large healthcare organizations with shared cost, closed health systems such as the Kaiser Permanente, insurance companies, hospice agencies, and stand-alone companies partnering with insurers [61, 63,64,65].

Benefits

As with all palliative care models, HBPC can assist patients with > 6-month prognosis who do not qualify for the Medicare hospice benefit or those who wish to continue receiving life-prolonging therapies unavailable to those on hospice. Seriously ill patients may struggle with transport to traditional palliative care clinics, and home-based programs are designed to bring comprehensive palliative care to patients in their home to improve quality of life and lower costs, mainly by avoiding hospital admissions [62]. HBPC care is still early in its development, but it has demonstrated reductions in ED visits, intensive care unit admission, hospitalization, and nursing home admissions for patients at the end of life [66, 67]. Improvement in costs is seen during the last month of life as it leads to more frequent death in the home and use of hospice [61, 68]. HBPC has been shown to improve symptoms such as pain, constipation, depression, fatigue, dyspnea, and anxiety [69]. It has also been shown to improve concordance between actual and preferred location of death [70].

Barriers

A national survey of HBPC organizations found a substantial lack of standardization of practice guidelines, oversight, and a lack of payment structures [71, 72]. Sustainable financing methods are lacking, and HBPC program design is not standardized to the same degree as hospice programs. These barriers contribute to a lack of patient, family, and provider understanding of HBPC, leading to challenges in referral and enrollment [71, 73]. Reimbursement is still developing for HBPC. Programs have been funded on a per-member per-month method by insurers and health systems as well as via CMS demonstration projects [74, 75].

Community paramedicine (CP)

Description and team composition

Mobile integrated healthcare (MIH) is a broad term including healthcare services delivered by many types of health professionals [76]. Community paramedicine (CP), while part of MIH, involves paramedics working to support and enrich existing programs and care plans with the goal of improving care for patients while decreasing ED visits [77]. This model of CP is still evolving, with several pilot programs working towards different aims depending on geographic location and regulatory body [78,79,80,81]. Some programs require staff, such as paramedics and/or emergency medical technicians (EMTs), to receive additional training, education, and skills to care for patients at home or in alternate destinations (e.g., primary care) [76]. Select CP pilot programs are connected with hospitals or care organizations and check on patients after hospital discharge or continue a specialized care plan while respecting patient wishes to be at home and avoid the discomfort of an ED visit according to patient preferences [82, 83].

Benefits

CP programs offer treatment to persons living with cancer suffering from burdensome symptoms or associated treatment toxicities that may prevent an ED visit. CP can deliver time-sensitive therapies such as rehydration and nausea control and even lab services [84]. They may provide a bridge to other health professionals, via telehealth or other forms of communication [77, 85,86,87,88,89]. For example, patients under hospice care, for example, may receive pain medication via MIH or CP programs while waiting for the arrival of a hospice nurse. In addition, many CP programs perform wellness checks, assess and address other at-home needs, and conduct social interventions impacting the future health and wellness of vulnerable populations [81, 82].

CP leverages the strengths of the out-of-hospital care system, previously focused on patient care and transportation, while honoring patient wishes and patient-centered care. Transportation to the ED is not always the best option for advanced cancer patients who may need only rehydration and/or labs and can be spared a lengthy, often uncomfortable ED visit [90, 91]. Paramedics can efficiently and effectively provide the care patients want or need and deliver care where patients choose to receive it. The infrastructure distributing paramedics geographically to serve community settings from rural to urban during all hours of the day and night already exists and operates under medical guidance as part of an organized system of care [84]. Moreover, paramedics are already trained to perform patient assessments outside the hospital, and generally, the public already maintains a high level of trust and appreciation for this group of clinicians.

Barriers

Due to the fact many CP programs are in pilot phase, evaluation of the impact of these programs is still in its infancy [92]. In terms of sustainability, CMS is currently piloting a new model Emergency Triage, Treat, and Transport (ET3) [93]. This voluntary, 5-year payment model aims to provide greater flexibility and reimbursement for alternative destinations or initiation and facilitation of treatment at the scene of an emergency response or via telehealth. The goal of the ET3 model is improved quality of care with reduced system costs through decreased ED transports and preventable hospitalizations resulting from those transports [93].

Hospice

Description and team composition

Hospice most commonly occurs at home with family providing the day-to-day care (called routine care), while the hospice agency provides medications, durable medical equipment, and frequent visits by a nurse-led interdisciplinary team (nurse, social worker, chaplain, home health aide, and physician) [94]. Nurse visits occur from once a week for stable patients to as often as 3 to 4 times a week for high-need patients, but a patient must have a caregiver in the home to receive home hospice. Hospice can also occur in a nursing facility if there is no home or caregiver. Patients with difficult-to-control symptoms requiring parental medications or closer monitoring can receive higher levels of hospice care with a 24-h nurse in the home (continuous care (CC)) to manage symptoms with frequent assessments/medication changes or in a skilled nursing facility (general inpatient care (GIP)) [95]. Medicare reimburses hospices with a much higher daily rate for skilled nursing facility care, but this care is scrutinized for overuse and is typically used for a few days for patients with out-of-control symptoms [96, 97]. Some hospitals have beds dedicated to hospice care that are managed by a local hospice agency, allowing the ED to admit directly to hospice within the hospital for high-need patients [98].

Benefits

Hospice is most beneficial if patients live at least a few weeks to get the full benefit of the service. Moving hospice enrollment upstream is important, since length of stay on hospice has dropped over the last 15 years to a median of 18 days [99, 100]. The ED is where patients present during a transition or a crisis and can be the ideal place to refer to hospice and avoid an unnecessary admission. Hospice agencies can admit patients from the ED directly to routine home care or general inpatient (GIP)/continuous care (CC) if they have high symptom burden [94]. If a hospital has a GIP unit inside their hospital, patients can be referred there if they meet criteria.

EDs and hospitals can build relationships with reliable, high-quality local hospice agencies to achieve direct referral to hospice from the ED. Some hospitals with inpatient GIP units housed within their hospital can expedite referrals of high symptom burden patients without admission to the medical ward. However, if a hospital does not have an inpatient hospice GIP unit, the hospice agency may be able to move them from the ED to a nursing facility where GIP is available [101]. This requires significant coordination and a strong relationship with local hospice agencies. An ED observation unit can be helpful for these patients to give more time to facilitate hospice placement [101]. ED or palliative care-based case managers or social workers familiar with hospice are integral to an effective transition to hospice care [102]. Standardizing ED processes and referral mechanisms may also facilitate the ED to hospice transition [103]. Reimbursement for hospice is well-established through Medicare and private insurance [104, 105].

Barriers

Hospice services are underutilized and frequently occur too late in the disease course to spare patients from burdensome care in the final weeks of life [106]. Patients are required to forgo life-sustaining therapies such as chemotherapy, radiation, and future hospitalization when they enroll in hospice which may delay hospice admission [107]. Patients and their clinicians often have a discordant understanding of a patient’s end-of-life goals. If a patient is on routine care on hospice and is unable to live at home due to homelessness or lack of caregiver in the home, they will need nursing home care while on hospice. The nursing home is not paid for by hospice which can be a financial barrier, if the patient is unable to pay out of pocket. Medicaid will pay for the nursing home stay if a patient is on routine hospice care, but many patients are not enrolled even though they may qualify, and the enrollment process can be lengthy, preventing enrollment on hospice from the ED [9, 108, 109].

Implications for emergency providers

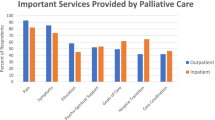

Patients with advanced cancer face myriad challenges in the final years of life. These challenges frequently result in ED visit and subsequent inpatient admission. Many new models of care exist and are being developed to attempt to address these challenges as a way to prevent some ED visits and avoid hospital admission altogether. The forms of palliative and hospice care discussed in this paper have variable penetration in different areas of the country as well as differences between health systems and insurers. Table 1 provides a snapshot summary of the characteristics of each model of care, while Fig. 1 depicts how they intersect. EM providers can educate themselves as to what palliative care and hospice programs are active in their area, recognizing not all services are available within all healthcare systems. Understanding what programs cancer patients in the ED already have at home, in addition to what they might be eligible, may help prevent future ED visits.

Conclusion

The breadth of acute and supportive care models to support persons living with advanced cancer has grown substantially. Most hospitals have inpatient palliative care consult services to assist patients who are admitted. Hospital admissions can be avoided by hospice admission occurring directly from the ED for patients with hospice goals. HBPC, outpatient palliative care, CP, and telehealth support patients who still seek disease-modifying therapies but need additional symptom management and psychosocial supports to prevent ED admissions. ED providers now have multiple tools they can leverage to improve care for cancer patients and potentially avoid ED transport and hospital admission. Advances in technology and retraining clinicians to work in new ways and in new settings have spurred innovation and the ways in which clinicians can care for patients in settings most aligned with their values and preferences. Meanwhile, reimbursement mechanisms have not always kept pace with the proliferation of care models, presenting a barrier to more widespread adoption of these practices.

References

Obermeyer Z, Clarke AC, Makar M, Schuur JD, Cutler DM. Emergency care use and the Medicare hospice benefit for individuals with cancer with a poor prognosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):3239. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13948.

Verhoef MJ, de Nijs E, Horeweg N, Fogteloo J, Heringhaus C, Jochems A, et al. Palliative care needs of advanced cancer patients in the emergency department at the end of life: an observational cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1097–107.

Caterino JM, Adler D, Durham DD, Yeung SCJ, Hudson MF, Bastani A, et al. Analysis of diagnoses, symptoms, medications, and admissions among patients with cancer presenting to emergency departments. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3): e190979. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0979.

Coyne CJ, Reyes-Gibby CC, Durham DD, Abar B, Adler D, Bastani A, et al. Cancer pain management in the emergency department: a multicenter prospective observational trial of the Comprehensive Oncologic Emergencies Research Network (CONCERN). Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(8):4543–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-05987-3.

Chun A. Geriatric practice: a competency based approach to caring for older adults. Springer International Publishing; 2020.

Thomas T, Clarke G, Barclay S. The difficulties of discharging hospice patients to care homes at the end of life: a focus group study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(7):1267–74.

Adams CE, Bader J, Horn KV. Timing of hospice referral: assessing satisfaction while the patient receives hospice services. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2009;21(2):109–16.

Grudzen CR, Stone SC, Morrison RS. The palliative care model for emergency department patients with advanced illness. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(8):945–50. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0011 Epub 2011 Jul 18. PMID: 21767164; PMCID: PMC3180760.

Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliat Care. 2017;10:1178224216688887.

Silva MD, Schack EE. Outpatient palliative care practice for cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic: benefits and barriers of using telemedicine. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(7):842–4.

Fine PG. Hospice underutilization in the U.S.: the misalignment of regulatory policy and clinical reality. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(5):808–15.

2020 Edition: Hospice Facts and Figures. www.nhpco.org/factsfigures. Accessed 2 July 2022.

Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4:5.

May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Kelley AS, Meier DE, Normand C, et al. Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745–52.

America’s Care of Serious Illness: a state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation’s hospitals. https://reportcard.capc.org/. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, Williams MP, Liberson M, Blum M, Della PR. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–90. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2007.0055 PMID: 18333732.

Ahluwalia SC, Chen C, Raaen L, Motala A, Walling AM, Chamberlin M, et al. A systematic review in support of the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Fourth Edition J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(6):831–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.008.

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

Ding J, Johnson CE, Qin X, Ho SCH, Cook A. Palliative care needs and utilisation of different specialist services in the last days of life for people with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30(1):e13331.

Yadav S, Heller IW, Schaefer N, Salloum RG, Kittelson SM, Wilkie DJ, et al. The health care cost of palliative care for cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(10):4561–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05512-y.

Kubendran S, Schockett E, Jackson E, Huynh-Le MP, Roberti F, Rao YJ, et al. Trends in inpatient palliative care use for primary brain malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(11):6625–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06255-0.

Woodrell CD, Goldstein NE, Moreno JR, Schiano TD, Schwartz ME, Garrido MM. Inpatient specialty-level palliative care is delivered late in the course of hepatocellular carcinoma and associated with lower hazard of hospital readmission. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(5):940–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.040.

Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, Hu M, Wang B, Ortiz JM, et al. Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):591–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252.

Jordan RI, Allsop MJ, ElMokhallalati Y, Jackson CE, Edwards HL, Chapman EJ, et al. Duration of palliative care before death in international routine practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18:368. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01829-x.

Zhuang H, Ma Y, Wang L, Zhang H. Effect of early palliative care on quality of life in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(1):e54–8.

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Leighl N, Rydall A, Rodin G, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ. 2016;188(10):E217-227. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.151171.

Finlay E, Newport K, Sivendran S, Kilpatrick L, Owens M, Buss MK. Models of outpatient palliative care clinics for patients with cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2019;15(4):187–93. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.18.00634.

Hui D. Palliative cancer care in the outpatient setting: which model works best? Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2019;20:17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-019-0615-8.

Mathews J, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Models of integration of specialized palliative care with oncology. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22(5):44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-021-00836-1.

Rabow MW, Dahlin C, Calton B, Bischoff K, Ritchie C. New frontiers in outpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22(4):465–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327481502200412.

Grudzen CR, Schmucker AM, Shim DJ, Ibikunle A, Cho J, Chung FR, et al. Development of an outpatient palliative care protocol to monitor fidelity in the emergency medicine palliative care access trial. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(S1):66–71. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0115.

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society Of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96–112. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474.

Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, Pirl WF, Park ER, Jackson VA, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and gi cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834–41. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046.

Fulton JJ, LeBlanc TW, Cutson TM, Porter Starr KN, Kamal A, Ramos K, et al. Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33(2):123–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318812633.

Hoerger M, Wayser GR, Schwing G, Suzuki A, Perry LM. Impact of interdisciplinary outpatient specialty palliative care on survival and quality of life in adults with advanced cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(7):674–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay077.

Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, Cassel JB, Cohen S, Jackson V, et al. Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(12):1540–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0153.

Rodin R, Swami N, Pope A, Hui D, Hannon B, Le LW, et al. Impact of early palliative care according to baseline symptom severity: secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Med. 2022;11(8):1869–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4565.

Groh G, Vyhnalek B, Feddersen B, Führer M, Borasio GD. Effectiveness of a specialized outpatient palliative care service as experienced by patients and caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):848–56. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0491.

McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B, Lo C, Pope A, Oza A, et al. Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: cluster randomised trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(1):163–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw438.

Rogers JL, Perry LM, Hoerger M. Summarizing the evidence base for palliative oncology care: a critical evaluation of the meta-analyses. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2020;14:1179554920915722. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179554920915722.

Yeh JC, Urman AR, Besaw RJ, Dodge LE, Lee KA, Buss MK. Different associations between inpatient or outpatient palliative care and end-of-life outcomes for hospitalized patients with cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(4):e516–24. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.21.00546.

Kayastha N, LeBlanc TW. Why are we failing to do what works? Musings on outpatient palliative care integration in cancer care. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(4):255–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.21.00794.

Hui D, De La Rosa A, Chen J, Dibaj S, Delgado Guay M, Heung Y, et al. State of palliative care services at US cancer centers: an updated national survey. Cancer. 2020;126(9):2013–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32738.

What is telehealth? https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth/what-is-telehealth. Accessed 12 Mar 2022.

Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, Hu M, Wang B, Ortiz JM, et al. Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):591–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252.

Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, Wolf SP, Shanafelt TD, Myers ER. Future of the palliative care workforce: preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med. 2017;130(2):113–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046.

Calton BA, Rabow MW, Branagan L, Dionne-Odom JN, Parker Oliver D, Bakitas MA, et al. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about telepalliative care. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(8):981–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0278.

Pimentel LE, Yennurajalingam S, Chisholm G, Edwards T, Guerra-Sanchez M, De La Cruz M, et al. The frequency and factors associated with the use of a dedicated supportive care center telephone triaging program in patients with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(5):939–44.

Grewal US, Terauchi S, Beg MS. Telehealth and palliative care for patients with cancer: implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Cancer. 2020;6(2):e20288. https://doi.org/10.2196/20288.

Riggs A, Breuer B, Dhingra L, Chen J, Portenoy RK, Knotkova H. Hospice enrollment after referral to community-based, specialist palliative care: impact of telephonic outreach. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(2):219–25.

Grudzen CR, Shim DJ, Schmucker AM, Cho J, Goldfeld KS. Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA): protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of specialty outpatient versus nurse-led telephonic palliative care of older adults with advanced illness. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e025692. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025692.

Chen YY, Guan BS, Li ZK, Li XY. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients’ quality of life and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(3):157–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16686777.

Ream E, Hughes AE, Cox A, Skarparis K, Richardson A, Pedersen VH, et al. Telephone interventions for symptom management in adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6(6):CD007568. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

Massimi A, De Vito C, Brufola I, Corsaro A, Marzuillo C, Migliara G, et al. Are community-based nurse-led selfmanagement support interventions effective in chronic patients? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173617. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173617.

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, et al. Effect of Electronic Symptom Monitoring on Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients With Metastatic Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2413–22.

Yamarik R, Meier M, Curtis J, Tan A, Tedeschi K. Can i talk to the doctor? Strategies for nurse-led palliative programs in engaging primary providers. 2022;63(5):795.

Yamarik RL, Tan A, Brody AA, Curtis J, Chiu L, Bouillon-Minois JB, et al. Nurse-led telephonic palliative care: a case-based series of a novel model of palliative care delivery. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2022;24(2):E3-e9.

Reinke LF, Sullivan DR, Slatore C, Dransfield MT, Ruedebusch S, Smith P, et al. A randomized trial of a nurse-led palliative care intervention for patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2022.0008. Epub ahead of print.

Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, Ritchie CS, Federman AD, Roberts L, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1180–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1849.

Lustbader D, Mudra M, Romano C, Lukoski E, Chang A, Mittelberger J, et al. The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0265.

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD007760. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2 PMID: 23744578; PMCID: PMC4473359.

Anthem, Inc. Completes acquisition of Aspire Health. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180618005754/en/Anthem-Inc.-Completes-Acquisition-of-Aspire-Health. Accessed 12 Mar 2022.

Aspire Health. https://aspirehealthcare.com/. Accessed 12 Mar 2022.

Palliative care. https://www.providence.org/services/palliative-care. Accessed 12 Mar 2022.

Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Fuhrer V, Gonzalez-Jaramillo N, Kopp-Heim D, Eychmüller S, Maessen M. Impact of home-based palliative care on health care costs and hospital use: AF systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(4):474–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951520001315.

Yosick L, Crook RE, Gatto M, Maxwell TL, Duncan I, Ahmed T, et al. Effects of a population health community-based palliative care program on cost and utilization. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(9):1075–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0489.

Pinderhughes ST, Lehn JM, Kamal AH, Hutchinson R, O’Neill L, Jones CA. Expanding palliative medicine across care settings: One Health system experience. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1272–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0375.

Ernecoff NC, Hanson LC, Fox AL, Daaleman TP, Kistler CE. Palliative care in a community-based serious-illness care program. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(5):692–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0174.

Cai J, Zhang L, Guerriere D, Coyte PC. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death for those in receipt of home-based palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(11):1460–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0582.

Hassankhani H, Rahmani A, Best A, Taleghani F, Sanaat Z, Dehghannezhad J. Barriers to home-based palliative care in people with cancer: a qualitative study of the perspective of caregivers. Nurs Open. 2020;7(4):1260–8.

Bowman BA, Twohig JS, Meier DE. Overcoming barriers to growth in home-based palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(4):408–12.

Enguidanos S, Cardenas V, Wenceslao M, Hoe D, Mejia K, Lomeli S, et al. Health care provider barriers to patient referral to palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(9):1112–9.

Bowman B. Home- based palliative care: there’s never been a better time Center to Advance Palliative Care, Center to Advance Palliative Care, 23 Nov. 2021, https://www.capc.org/blog/palliative-pulse-may-2016-home-based-palliative-care/2021/#:~:text=AF%3A%20The%20home%2Dbased%20program,in%20our%20home%2Dbased%20program. Accessed 12 Mar 2022.

Rahman A, Coulourides Kogan A, Lewis N, Lomeli S, Enguidanos S. Home-Based Palliative Care Organizations Struggle to Survive and Thrive in a Competitive Market. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022:10499091211073462. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211073462. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35234074.

Choi BY, Blumberg C, Williams K. Mobile integrated health care and community paramedicine: an emerging emergency medical services concept. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(3):361–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.005.

Thurman WA, Moczygemba LR, Tormey K, Hudzik A, Welton-Arndt L, Okoh C. A scoping review of community paramedicine: evidence and implications for interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2021;35(2):229–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1732312.

Leyenaar MS, McLeod B, Jones A, Brousseau AA, Mercier E, Strum RP, et al. Paramedics assessing patients with complex comorbidities in community settings: results from the CARPE study. CJEM. 2021;23(6):828–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-021-00153-4.

Breyre A, Taigman M, Salvucci A, Sporer K. Effect of a Mobile Integrated Hospice Healthcare Program on Emergency Medical Services Transport to the Emergency Department. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(3):364–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2021.1900474. Epub 2021 Mar 30. PMID: 33689535.

Somers S, Brown J, Fitzpatrick S, Landi C, Gingold DB, Marcozzi D. Innovative use of emergency medicine providers in an urban setting to reduce overutilization of 9–1-1. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(6):836–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.07.003.

Agarwal G, Angeles R, Pirrie M, Marzanek F, McLeod B, Parascandalo J, et al. Effectiveness of a community paramedic-led health assessment and education initiative in a seniors’ residence building: The Community Health Assessment Program through Emergency Medical Services (CHAP-EMS). BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-017-0119-4.

Guo B, Corabian P, Yan C, Tjosvold L. Community Paramedicine: Program Characteristics and Evaluation [Internet]. Edmonton (AB): Institute of Health Economics; 2017. PMID: 31670923.

Masterson Creber RM, Daniels B, Munjal K, Reading Turchioe M, Shafran Topaz L, Goytia C, et al. Using mobile integrated health and telehealth to support transitions of care among patients with heart failure (MIGHTy-Heart): protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e054956. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054956.

Glenn M, Zoph O, Weidenaar K, Barraza L, Greco W, Jenkins K, Paode P, Fisher J. State Regulation of Community Paramedicine Programs: A National Analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(2):244–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1371260. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29023167.

Juhrmann ML, Vandersman P, Butow PN, Clayton JM. Paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings: a systematic integrative review with thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2022;36(3):405–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211059342.

van Vuuren J, Thomas B, Agarwal G, MacDermott S, Kinsman L, O’Meara P, et al. Reshaping healthcare delivery for elderly patients: the role of community paramedicine; a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06037-0.

Chan J, Griffith LE, Costa AP, Leyenaar MS, Agarwal G. Community paramedicine: a systematic review of program descriptions and training. CJEM. 2019;21(6):749–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.14.

Pang PS, Litzau M, Liao M, Herron J, Weinstein E, Weaver C, et al. Limited data to support improved outcomes after community paramedicine intervention: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(5):960–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.036.

Gregg A, Tutek J, Leatherwood MD, Crawford W, Friend R, Crowther M, et al. Systematic review of community paramedicine and EMS mobile integrated health care interventions in the United States. Popul Health Manag. 2019;22(3):213–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0114.

Tomar A, Ganesh SS, Richards JR. Transportation preferences of patients discharged from the emergency department in the era of ridesharing apps. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(4):672–80.

Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):976–93.

Bigham BL, Kennedy SM, Drennan I, Morrison LJ. Expanding paramedic scope of practice in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17(3):361–72.

Emergency triage, treat, and transport (ET3) model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/et3. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Lamba S, Quest TE. Hospice care and the emergency department: rules, regulations, and referrals. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(3):282–90.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Home. https://www.nhpco.org/. Accessed 2 July 2022.

Miller SC, Mor VN. The role of hospice care in the nursing home setting. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(2):271–7.

Update to hospice payment rates, hospice cap, hospice wage index and hospice pricer for FY 2021 paid. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm11876.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2022.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospice. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospice. Accessed 7 July 2022.

Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, Bynum J, Tyler D, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–21.

Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, Bunker J, Lima J, Ogarek J, et al. Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2000–2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264–71.

Chung K, Richards N, Burke S. Hospice agencies’ hospital contract status and differing levels of hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(3):341–9.

Medicine Io. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2015. p. 103.

Koh MYH, Lee JF, Montalban S, Foo CL, Hum AYM. ED-PALS: a comprehensive palliative care service for oncology patients in the emergency department. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(7):571–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119825847.

Morrison RS. Models of palliative care delivery in the United States. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7(2):201–6.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Hospice Benefits. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/02154-Medicare-Hospice-Benefits.PDF. Accessed 3 July 2022.

Cagle JG, Lee J, Ornstein KA, Guralnik JM. Hospice utilization in the United States: a prospective cohort study comparing cancer and noncancer deaths. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):783–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16294.

Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Why don’t patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1009–19.

Raphael CAJ, Fowler N. Financing end-of-life care in the USA. J R Soc Med. 2001;94(9):458–61.

Patel MN, Nicolla JM, Friedman FAP, Ritz MR, Kamal AH. Hospice use among patients with cancer: trends, barriers, and future directions. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(12):803–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00309. Epub 2020 Nov 13 PMID: 33186083.

Tuca A, Gómez-Martínez M, Prat A. Predictive model of complexity in early palliative care: a cohort of advanced cancer patients (PALCOM study). Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):241–9.

Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):852–65.

Ritchey KC, Foy A, McArdel E, Gruenewald DA. Reinventing palliative care delivery in the era of COVID-19: how telemedicine can support end of life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(11):992–7.

Ullrich A, Ascherfeld L, Marx G, Bokemeyer C, Bergelt C, Oechsle K. Quality of life, psychological burden, needs, and satisfaction during specialized inpatient palliative care in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):31.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nicole Zhao for her technical and intellectual assistance throughout the review process.

Funding

This work is (partially) supported within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory by cooperative agreement (UG3/UH3 AT009844) from the National Institute on Aging. This work also received logistical and technical support from the NIH Collaboratory Coordinating Center through cooperative agreement U24AT009676. Support was also provided by the NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Administrative Supplement for Complementary Health Practitioner Research Experience through cooperative agreement (UH3 AT009844) and by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number (UH3AT009844). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work was (partially) supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award (PLC-1609–36,306). The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, development, writing, and revisions of this manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grudzen, C.R., Barker, P.C., Bischof, J.J. et al. Palliative care models for patients living with advanced cancer: a narrative review for the emergency department clinician. Emerg Cancer Care 1, 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44201-022-00010-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44201-022-00010-9