Abstract

Background

SARS‐COV‐2 infection reframed medical knowledge in many aspects, yet there is still a lot to be discovered. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) can cause neuropsychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial impairments. Literature regarding the cognitive impact of COVID-19 is still limited.

This study aims to evaluate cognitive function, anxiety, and depression among patients with coronavirus disease 19.

Methods

Sixty COVID-19 patients were recruited and sub-grouped according to the site of care into three groups, home isolation, ward, and RICU, and compared with 60 matched control participants. Entire clinical history, O2 saturation, mini-mental state examination (MMSE), Hamilton’s anxiety (HAM-A), and depression rating scales (HAM-D) were assessed.

Results

MMSE showed significantly lowest results for the ICU group, with a value of 21.65 ± 3.52. Anxiety levels were the highest for the ICU group, with a highly significant difference vs. the home isolation group (42.45 ± 4.85 vs. 27.05 ± 9.52; p< 0.001). Depression values assessed showed a highly significant difference in intergroup comparison (44.8 ± 6.64 vs. 28.7 ± 7.54 vs. 31.25 ± 8.89; p<0.001, for ICU vs. ward vs. home group, respectively).

MMSE revealed a significant negative correlation with age and education level, anxiety level had significant negative correlations with severity of illness and male gender, and depression level had highly significant negative correlations with severity of illness and male gender.

Conclusion

Both cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms were affected in COVID-19 cases, especially in ICU-admitted patients. The impact of these disorders was significant in older age, lower oxygen saturation, and severe disease.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT05293561. Registered on March 24, 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 results in various symptoms with multi-organ affection, including fever, cough, grave respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal manifestations, and fatigue [1]. Continuous neurological and psychological evaluation efforts revealed that headache, dizziness, and cerebrovascular events had been frequently reported [2]. Anosmia and ageusia were reported as early indicators of SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting that early neurological involvement may be relevant [3].

Public health emergencies such as COVID-19 are likely to cause adverse neuropsychiatric impacts. Cognitive impairments after SARS‐COV‐2 infection were noticed, including poor concentration and declined memory as well as insomnia, anxiety, and depression symptoms [4].

The battle against COVID-19 is continuing worldwide. People’s adherence to confinement regulations and response to vaccination campaigns is essential and primarily affected by their knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19. Home isolation and social distancing are also associated with fear, frustration, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [5].

During the acute phase of COVID-19 infection, about 36% of cases develop neurological symptoms, of which 25% can be attributed to the direct involvement of the central nervous system [6]. Patients who show neurological symptoms included cases with or without pre-existing neurological disorders [7]. In intensive care units, patients showed agitation, confusion, and corticospinal tract signs such as enhanced tendon reflexes and clonus. COVID-19 can further lead to changes in coagulation and, in particular, to inflammation-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [3].

This study aims to evaluate cognitive function, anxiety, and depression among patients with coronavirus disease 19.

Patients and methods

Study participants and design

This prospective cross-sectional case-control study was performed on 60 COVID-19 patients in the age group of 18–70 years who were diagnosed using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm the diagnosis of COVID-19 and belonging to either gender. Data of 20 patients recruited from home isolation at the first visit to the outpatient clinic, 20 patients included from the hospital isolation ward, and 20 patients recruited from respiratory isolation ICU, Chest Department of Assiut University Hospital from January 2021 to October 2021.

Based on the Egyptian MOH protocol (version 1.4, Nov 2020) [8], patients were classified into mild, moderate, severe, and critical; hence triaged to receive treatment either at the home, ward, or ICU.

Mild cases were symptomatic cases with lymphopenia or leucopenia with no radiological signs of pneumonia with no risk factors, including age 65, temperature > 38 °C, SaO2 ≤ 92%, heart rate ≥ 110, respiratory rate ≥ 25/min., neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio on CBC ≥ 3.1, uncontrolled comorbidities, immunosuppressive drug, pregnancy, active malignancy, on chemotherapy, and obesity (BMI>40).

Moderate showed positive chest radiological finding of pneumonia with oxygen saturation ≥ 92%.

Severe cases included patients with either SpO2 ≤92% on room air, PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300, or chest CT showing more than 50% lesion.

Critically ill patients have respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multi-organ dysfunction.

Inclusion criteria

All patients between the ages of 18 and 70 attending the chest department outpatient clinic or admitted to the chest department isolation unit and RICU were eligible for enrollment in the current study.

Exclusion criteria

Age under 18, other end organ failure conditions, previous neurological or psychiatric involvement, disturbed level of consciousness, uncooperative patients or cannot perform the psychometric tests, those who needed MV or sedation, and refusal to sign the consent.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data

Included patients underwent careful history taking, and associated comorbidities and the presence of symptoms were recorded. Patients were identified by with international classification of diseases (ICD-10). Comorbidities include diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), moderately to severe renal dysfunction (creatinine > 3mg or renal failure), hepatic dysfunction (viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatic failure), ischemic heart disease (IHD), and heart failure. Radiological assessment by chest computed tomography (CT) was also done to classify the patients according to severity and level of care.

Pulse oximeter saturation

Oxygen saturation was recorded during recruitment (SpO2).

Mini-mental state examination (MMSE)

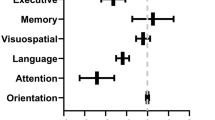

A 30-point test used to assess cognitive function includes tests of orientation, attention, memory, language, and visual-spatial skills. MMSE scores 24–30: no cognitive impairment, 19–23: mild cognitive impairment, 10–18: moderate cognitive impairment, ≤ 9: severe cognitive impairment. MMSE is an eleven items test and on average performing the test requires 5–10 min [9, 10].

Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM-A)

This consists of 14 items and measures both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety). Each item is scored on a scale of 0 (not present) to 4 (severe), with a total score range of 0–56, where a score ≤ 17 indicates mild anxiety, 18–24 mild to moderate severity, and more than 24 moderate to severe anxiety. Usually, the test requires 15–20 min for its performance [11, 12].

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

The original HAM-D has 21 items, but scoring is based only on the first 17. Scores less than or equal to 7 indicate normal response, 8–13 mild depression, 14–18 moderate, 19–22 severe, and more than 22 very severe depression. On average, the test time is between 15 and 20 min [13,14,15].

Statistical analysis

Data was collected and analyzed using SPSS (statistical package for social sciences) program (version 24, IBM and Armonk, New York). Continuous data were expressed in the form of the mean (± SD) and compared by the Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test for groups of more than two, while nominal data were expressed in the form of frequency (percentage) and compared by the chi-square test. Different correlations of continuous variables in the study were determined with Spearman’s correlation.

Sampling and sample size

Sampling was done by non-probability convenient sampling technique. The sample size was estimated by the Open Epi V.3.01 computer program.

Matching and masking

All patients fulfilling inclusion and exclusion criteria were eligible for participation in the study regardless of prognosis or any other factor that may influence the study results. The assessment was done shortly after the initial diagnosis and site of care decision. The control group was selected from age, gender, residence, and educational level matched patients’ relatives and healthy volunteers. The neuropsychological studies were performed by a single neuropsychologist who was blinded to patient prognosis and laboratory data upon performing the psychometric studies.

Ethical consideration

All participants or their legal guardians gave informed written consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University (IRB: 04-2023-300055), and it was carried out under the Declaration of Helsinki with clinical trials ID: NCT05293561.

Results

The current study enrolled 120 personnel; 60 health, age, and sex-matched controls and 60 patients with COVID-19 disease; 20 patients experienced severe illness and received care in the respiratory intensive care unit (RICU)—none of them was MV and five of them required intermittent HFNC; 20 patients were isolated at the ward; and 20 were isolated at home. The mean age of patients was 52.58 ± 17.29 years vs. 47.52 ± 15.05 for the control group. Both groups showed no significant difference regarding baseline data, including gender, smoking, education level, residence, and associated comorbidities (Table 1). Subgroup analysis of recruited patients revealed insignificant differences as regards age, sex, smoking status, education level, and residence (p> 0.05) (Table 2). There was no significant difference between groups regarding comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, and cardiac dysfunction (Table 3). Patients with ICU admission as the level of care showed the lowest values regarding oxygen saturation levels of 73.4 ± 12 versus 86.90 ± 3.87 for the ward isolation group and 93.7 ± 2.13 for the home isolation group (Table 3).

Mini-mental state evaluation results showed a significant difference between the ICU group versus the ward group and home isolation group (21.65 ± 3.52 vs. 24.05± 3.72, p=0.01; 21.65 ± 3.52 vs. 24.40 ± 3.4, p= 0.001), respectively (Table 4).

Comparison between the three groups regarding anxiety levels showed a highly significant difference (p< 0.001), also intergroup comparison displayed a significant difference between the ICU group vs. home group and ward group vs. home group (42.45 ± 4.85 vs. 27.05 ± 9.52 & 33.15 ± 9.12 vs. 27.05 ± 9.52), respectively (Table 5).

Comparison between the three groups regarding depression levels showed a highly significant difference (p < 0.001), also intergroup comparison displayed a significant difference between ICU group vs. home group and ward group vs. home group (44.8 ± 6.64 vs. 31.25 ± 8.89 & 28.7 ± 7.54 vs. 31.25 ± 8.89), respectively (Table 6).

Cognitive dysfunction showed a significant positive correlation with SpO2 level (r=0.283, p=0.029) and a significant negative correlation with age. Anxiety level values had a significant positive correlation with SpO2 level (r=0.566, p< 0.001) and negative correlations with the severity of illness. Depression level values showed significant positive correlations with SpO2 level (r=0.546, p< 0.001) and negative correlations with severity of illness (Table 7).

Discussion

Generally, the exact prevalence of cognitive and psychological disturbances in COVID-19 disease is unknown. It varies considerably across studies, which can be explained by the different neurological and psychological tests used in different studies.

Our study detected moderate to severe cognitive impairment in nearly 13% of the study group, severe anxiety in nearly 81%, and severe level of depression in nearly 88% of patients.

Neuropsychiatric affection in the course of SARS-COV-2 has been described in many studies [6, 7]. The pathophysiology of such involvement has been described due to different etiologies. Theories include direct viral invasion of neurons, affection of vascular endothelium, affection of the blood-brain barrier, and increased coagulation state. Also, some neurological conditions have been reported to be closely associated with SARS-COV-2 infection, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, peripheral neuritis, and encephalopathy [16,17,18]. Cognitive impairment can partly be explained by admission to the intensive care unit in critical illness [19].

In a study by Egbert et al. on COVID-19 patients, many cerebral abnormalities were described in 34% of patients as white matter hyperintensities, cerebral hemorrhage, and infarction [20].

Neuro-inflammation reported in COVID-19 patients could be a pathogenesis to neurocognitive impairment in covid-19 patients [21]. Altered host immune response and cytokine storm syndrome is another key factor for cognitive impairment in the course of illness [22]. Increased level of cytokine interleukins (IL)-1ß has been linked to the presence of depression and anxiety in COVID-19 patients than those with normal (IL)-1ß level [23, 24].

Wang et al. enrolled a sample of young adults with COVID-19 affection; psychological impairment was present in more than 50% of the study group, with moderate to severe impairment [25].

In agreement with our results, Mazza and colleagues enrolled a group of young adults affected with COVID-19 infection in assessing stress levels. They reported high to very high-stress levels in 29% of them [26].

The duration and extent of neuropsychiatric affection during SARS-COV-2 are still debated in the literature. Still surprisingly, some studies reported the persistence of symptoms for more than 2 months after the SARS-COV-2 infection had been resolved [27]. Even the expression long COVID has been used in literature [28].

Surprisingly, Huang and colleagues’ study in a group of COVID-19 survivors from Wuhan reported some neuropsychiatric manifestations after 6 months of acquiring a SARS-COV-2 infection, including muscular weakness, easy fatigability, anxiety, and depression [28].

In agreement with our study, Morin et al. enrolled 478 COVID-19 patients after the resolution of infection. They reported cognitive impairment in 21% of them; such symptoms were absent before infection, 177 patients were hospitalized, and they detected the presence of cognitive impairment using the MoCA score in 38% of them [29].

Mattioli et al., studying the cognitive impairment in COVID-19 patients in 120 patients and 30 age and sex-matched control, observed memory difficulties in 6.6 % of patients and irritability and anxiety in 5 % of patients. Using neurophysiological tests’ scores and DASS scores, specifically MMSE, was slightly impaired compared to the control group but with no significant difference. At the same time, there were significant differences between the two groups in DASS-21 anxiety, stress, and depression scores [30].

We attribute the difference between results in MMSE to the difference in the study group in which Mattioli et al. study group were all well-educated, healthy coworkers and only two patients were admitted to the ICU, and 97.6% of his study group did not need oxygen therapy. They related the absence of significant difference due to the selection of mild to moderate cases of COVID-19 patients [30].

In agreement with our results, Schou et al., in an important meta-analysis using data from 66 studies, reported that the most frequent psychiatric impairments were depression and anxiety and closely linked to the severity of disease and duration of hospitalization and that symptoms persist after the resolution of the infection. Also, baseline comorbidities are an essential factor in developing anxiety and depression. He also reported that cognitive decline is present in 27 studies, including deficits in attention, memory, and concentration [31].

In another meta-analysis by Badenoch et al., 51 studies were eligible to be enrolled in his analysis with the sum of 18,917 participants; depression was found in 12.9% of patients, anxiety in 19.1% of patients, and 20.2% showed cognitive impairment [32].

Hu et al. studied 85 inpatients with COVID-19 affection; 45.9% were affected with depression, 21.2% with mild, 50.3% with moderate, and 8% with severe depression. Anxiety was found in 37.8 % of patients; 22.4% mild, 11.8% moderate, and 4.7% expressed severe anxiety. Kong et al. studied 144 patients, using the hospital anxiety and depression scale; anxiety and depression were found in 34.7% and 28.4% of patients, respectively [23].

In agreement with our results, Khanal and his colleagues who enrolled 372 home-isolated COVID-19 patients reported that 52.7% of the study group had borderline depression and 26.3% had manifest depression. They contributed to the significant level of depression among home-isolated patients that exceed the centrally isolated patient in some literature to COVID-19-related symptoms, fear of deterioration, and lack of medical care [33]. Another study by Gao et al demonstrated that exposure to social media and the outbreak news was associated with a high level of depression [34].

We must acknowledge the following limitations to our study: the study is single-centered; thus, results could not be generalized due to socio-demographic variabilities. Although cognitive affection anxiety and depression associated with COVID-19 infection are reported in many studies, the etiological bases beneath are still not fully studied; the manifestations are multifactorial and could be related to the disease itself, medication, and/or ICU admission.

Conclusion

Cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression are common findings in COVID-19 patients and are directly proportional to the severity of illness, oxygen saturation, and age. We recommend continuous observation of those impairments in COVID-19 patients, especially critically ill patients. We encourage further research to alleviate those symptoms and decrease the burden of those impairments through SARS-COV-2 infection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DASS:

-

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale

- DIC:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- FiO2 :

-

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- HAMA-A:

-

Hamilton anxiety rating scale

- HAMA-D:

-

Hamilton Depression rating scale

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MoCA:

-

Montreal cognitive assessment

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- MMSE:

-

Mini-mental state examination

- PaO2 :

-

Arterial pressure of oxygen

- RICU:

-

Respiratory intensive care unit

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-COV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SPO2 :

-

Saturation of peripheral oxygen

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

References

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395(10223):497–506

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323(11):1061–9

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, Blecic S, El Afia F, Distinguin L, Chekkoury-Idrissi Y (2020) Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277(8):2251–61

Xu K, Cai H, Shen Y, Ni Q, Chen Y, Hu S, Li J, Wang H, Yu L, Huang H, Qiu Y (2020) Management of COVID-19: the Zhejiang experience. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 49(2):147–57

Ajilore K, Atakiti I, Onyenankeya K (2017) College students’ knowledge, attitudes and adherence to public service announcements on Ebola in Nigeria: suggestions for improving future Ebola prevention education programmes. Health Education Journal. 76(6):648–60

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X (2020) Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 77(6):683–90

Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, Collange O, Boulay C, Fafi-Kremer S, Ohana M, Anheim M (2020) Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 382(23):2268–70

Masoud H, Elassal G, Hassany M, Shawky A, Hakim M, Zaky S, Baki A, Abdelbary A, Kamal E, Amin W, Attia E, & Ibrahem H, & Eid Al. (2020). Management protocol for COVID-19 patients MoHP protocol for COVID19 November 2020.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–98

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF (1993) Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. Jama. 269(18):2386–91

Hamilton MA (1959) The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 32(1):50–5

Vaccarino AL, Evans KR, Sills TL, Kalali AH (2008) Symptoms of anxiety in depression: assessment of item performance of the Hamilton anxiety rating scale in patients with depression. Depression and Anxiety. 25(12):1006–13

Hamilton M (1960) Depression rating scale. Neurol Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 23:56–62

Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB (2004) The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal of Psychiatry. 161(12):2163–77

Kendrick T, Pilling S, Mavranezouli I, Megnin-Viggars O, Ruane C, Eadon H, Kapur N (2022) Guideline Committee. Management of depression in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 378:o1557

Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, Nortley R, Wiethoff S, Bharucha T, Jayaseelan DL, Kumar G, Raftopoulos RE, Zambreanu L, Vivekanandam V (2020) The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 143(10):3104–20

Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S (2020) Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol 77(8):1018–27

Alberti P, Beretta S, Piatti M, Karantzoulis A, Piatti ML, Santoro P, Viganò M, Giovannelli G, Pirro F, Montisano DA, Appollonio I (2020) Guillain-Barré syndrome related to COVID-19 infection. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 7(4):e741

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, Moons KG (2013) Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 369(14):1306–16

Egbert AR, Cankurtaran S, Karpiak S (2020) Brain abnormalities in COVID-19 acute/subacute phase: a rapid systematic review. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 1(89):543–54

Divani AA, Andalib S, Di Napoli M, Lattanzi S, Hussain MS, Biller J, McCullough LD, Azarpazhooh MR, Seletska A, Mayer SA, Torbey M (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 and stroke: clinical manifestations and pathophysiological insights. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 29(8):104941

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ (2020) COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 395(10229):1033–4

Hu Y, Chen Y, Zheng Y, You C, Tan J, Hu L, Zhang Z, Ding L (2020) Factors related to mental health of inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 1(89):587–93

Kong X, Zheng K, Tang M, Kong F, Zhou J, Diao L, Wu S, Jiao P, Su T, Dong Y (2020) Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. MedRxiv. 30:2020–03

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International journal of environmental research and public health. 17(5):1729

Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, Roma P (2020) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International journal of environmental research and public health. 17(9):3165

Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F (2020) Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 324(6):603–5

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, Luo J (2021) 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet. 397(10270):220–32

Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, Colle R, Figueiredo S, Harrois A, Gasnier M, Lecoq AL, Meyrignac O, Noel N, Baudry E (2021) Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA 325(15):1525–34

Mattioli F, Stampatori C, Righetti F, Sala E, Tomasi C, De Palma G (2021) Neurological and cognitive sequelae of Covid-19: a four month follow-up. Journal of neurology. 268(12):4422–8

Schou TM, Joca S, Wegener G, Bay-Richter C (2021) Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19–a systematic review. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 1(97):328–48

Badenoch JB, Rengasamy ER, Watson C, Jansen K, Chakraborty S, Sundaram RD, Hafeez D, Burchill E, Saini A, Thomas L, Cross B (2022) Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Commun 4(1):fcab297

Khanal P, Paudel K, Mehata S, Thapa A, Bhatta R, Bhattarai HK (2022) Anxiety and depressive symptoms among home isolated patients with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study from Province One, Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(9):e0001046

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H, Dai J (2020) Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 15(4):e0231924

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMS, AARMH, AMAT, and WGEK: conception and design. AMS, AMAT, and WGEK: data collection. AMS and WGEK: statistical analysis. AMS, AARMH, AMAT, and WGEK: medical writing. The authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board and ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration (IRB: 04-2023-300055).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaddad, A.M.A.K., Hussein, A.A.R.M., Tohamy, A.M.A. et al. Cognitive impact on patients with COVID-19 infection. Egypt J Bronchol 17, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-023-00213-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-023-00213-6