Abstract

Background

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an abnormal polyclonal proliferation of Langerhans cells that affect different parts of the body. Temporal bone involvement is quite common among the involved sites. The etiology is unknown. Diagnosis is based on symptoms, imaging, and histopathology. Especially LCH in temporal bone is confused with acute or subacute otitis media. There are many treatment options in LCH.

Case presentation

Here, a 2-year-old pediatric patient with pain in the right ear was diagnosed as having LCH as a result of the examinations. MRG revealed multiple lesions in the temporal bone, sphenoid bone, and clivus. She was treated with steroids and vinblastine.

Conclusion

Possible tumoral formations should be kept in mind when children complain of otalgia and otitis media-like clinical picture for a long time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) are tumors of unknown etiology that affect children and young adults, characterized by clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells [1]. LCH can occur in different clinical presentations, ranging from unifocal or multifocal bone lesions or other tissues to multi-organ involvement involving the lung, liver, pituitary gland, skin, mucous membranes, lymphatics, or other organs [1, 2]. Temporal bone involvement is not uncommon. Common otological symptoms are hearing loss, otalgia, otorrhea, and soft tissue swelling in the mastoid or temporal region [3].

It is important to recognize the otological findings of LCH. Because the systemic findings of the disease are more pronounced, so otological findings may be overlooked. In addition, otological findings of LCH may mimic diseases such as otitis externa, otitis media, aural polyps, acute mastoiditis, chronic otitis media, and metastatic lesions [4].

In this case report, a child with LCH who was initially treated for acute otitis media will be discussed in light of the literature.

Case presentation

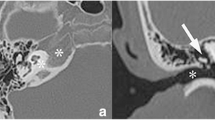

Written informed consent for the publication of this report was obtained from the patient’s father. A 2-year-old girl applied to our clinic in 2014 with the complaint of otalgia in the right ear and night restlessness for 1 month. She was treated with a combination of amoxicillin-clavulanate in another center for about 3 weeks due to acute otitis media. On examination of the patient, it was observed that the right external auditory canal (EAC) was slightly narrowed and the right tympanic membrane had a hyperemic and opaque appearance. The left ear was uninvolved. In the audiological examination, the right ear failed while the left ear passed from transient otoacoustic emission (t-OAE). In auditory brainstem response (ABR), the click stimulus test revealed a fifth wave at 20 dB nHL in the left ear and 40 dB nHL in the right ear. These medical history and examination findings warrant computerized tomography (CT) of the temporal bone. An enlarged soft tissue mass, starting from EAC on the right, narrowing the EAC, filling the middle ear, partly eroding the ossicles, and destroying the mastoid cell wall and petrous and squamous parts, with irregular and limited intracranial extension, was seen on CT (Fig. 1). Temporal bone magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed multiple lesions in the skull, the first lesion of 40×20×27 mm in mastoid cells on the right, the second lesion involving greater wing of the left sphenoid bone, and the third lesion of 10 mm in the clivus. The second lesion of 19×16×18 mm extended to the left orbital wall and the pterygopalatine fossa (Fig. 2). Biopsy was performed from the mass in the right mastoid taken under general anesthesia.

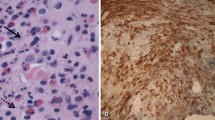

Microscopic examination of biopsy material composed of small tissue fragments showed oval cells with indented, folded nuclei, fine chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderately abundant, slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm in an eosinophil-rich inflammatory background. Nuclear atypia was minimal (Fig. 3a). Immunohistochemical (IHC) studies revealed that these cells were positive for S100 protein, CD1a, and Langerin/CD207 (Fig. 3b).

The histopathologic diagnosis was Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, and C reactive protein were normal. Urinalysis showed no anomalies. A chest radiograph was also normal. Skeletal survey and ultrasonography of the abdomen were normal.

Steroid and vinblastine treatment was given to the patient in a pediatric oncology unit. During the 7-year follow-up of the patient, there was no complaint and no recurrence was observed.

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare, poorly understood disease. Despite LCH being considered a non-hereditary disorder, a subset of LCH is familial [5]. Currently, neoplastic or inflammatory disease is primarily accused with predisposing factors [1, 6]. Although it can be seen in any age group, it mostly occurs in childhood. The median age at diagnosis is between 1 and 4 years of age.

It is slightly more common in boys than girls. The clinical picture can range from solitary or multifocal bone lesions to common diseases with multiorgan involvement [1]. Temporal bone involvement is seen in 15-60% of cases, and bilateral involvement is seen in 25–30% of cases. In addition to the temporal bone, the head and neck area may be involved, including the orbital bone, mandible, scalp, maxillary bone, and facial skin. Clinical findings vary depending on the location. Therefore, LCH has no specific symptoms [7]. It involves the most common mastoid process in the temporal bone and can easily spread to the middle and outer ear.

Otological findings are similar to otitis media, otitis externa, and cholesteatoma [1]. This diversity in clinical appearance may mislead the physician. Misdiagnosis rate increased to 72.7% [8]. LCH can often be confused with acute otitis, chronic otitis, and its complications, which are unresponsive to treatment and more common in children. This situation causes a delay in diagnosis and treatment. The most common otological symptoms are otorrhea, swelling in the mastoid region, external ear canal polyp, and hearing loss. Conductive or mixed hearing loss is common. Sensorineural hearing loss is rarely seen due to cochlear damage and bone erosion in the internal auditory or semicircular canals [3].

Clinical presentation should be investigated in detail along with imaging methods. Laboratory examinations are required in cases with multiple system involvement (complete blood count, coagulation, and liver function tests). Radiologically, a bone scan is required. Typically, widespread lytic lesions with well-defined soft tissue edges appear without sclerotic margins [9]. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is preferred to evaluate temporal bone involvement and to monitor treatment response. In HRCT, it is typically seen as sharp ‘beveled edges’ lytic lesions associated with soft tissue mass. However, only findings related to the infectious process can be seen in some cases [10]. Diagnosis with MRI without CT may be overlooked [6]. On MRI, LCH lesions were typically found to be hypointense on T1- and isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted images with avid gadolinium uptake [2]. Definitive diagnosis requires lesion biopsy for histopathological examination. Birbeck granules are observed with electron microscopy. LCH cells stain positively with antibodies to S100, CD1a, and/or CD207/Langerin. Staining with CD1a or CD207/Langerin confirms the diagnosis of LCH. CD-207/Langerin is crucial for the diagnosis since it can be an indicator of the presence of Birbeck granules. Also, the BRAF mutation is found in more than 50% of LCH cases. However, the allele frequency is very low. This may therefore lead to frequent false-negative molecular results if sensitive methods are not employed.

There are several treatment options available after diagnosis, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, intralesional steroid injection, and targeted therapy. These can be used alone or in combination depending on the extent, grade, and severity of the disease [11,12,13]. While surgery is preferred in a single-system disease, chemotherapy is used in multisystem diseases. Radiotherapy is no longer recommended for the treatment of temporal bone LCH [1]. In this case, the pediatric hematology and oncology department used chemotherapy and steroids after diagnosis due to multisystem presentation. The patient did not have any complaints during the 7-year follow-up, and her annual controls continue. The patient is followed by direct radiographs.

Conclusion

Mastoid bone may be involved by LCH. Therefore, this disease should be kept in mind when children complain of a clinical picture like ear pain and otitis media for a longer time than the usual duration. Therefore, a detailed medical history, careful examination, and audiological study should be done with CT and MRI for such patients. In cases that do not respond to treatment, one should suspect otitis media and its related complications, and LCH should be kept in mind. Radiologic workup and pathological diagnosis should be performed.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Gupta G, Jain A, Grover M (2018) Successful Cochlear Implantation in Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: A Rare Case. Cochlear Implants Int 19(2):115–118

Modest MC, Garcia JJ, Arndt CS, Carlson ML (2016) Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Temporal Bone: A Review of 29 Cases at a Single Center. Laryngoscope 126(8):1899–1904

Saliba I, Sidani K, El Fata F, Arcand P, Quintal MC, Abela A (2008) Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 72(6):775–786

Skoulakis CE, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, Bizaki AJ, Stavroulaki P, Helidonis ES (2008) Langerhans cell histiocytosis presented as bilateral otitis media and mastoiditis. Turk J Pediatr. 50(1):70–73 PMID: 18365596

Aricò M, Nichols K, Whitlock JA, Arceci R, Haupt R, Mittler U, Kühne T, Lombardi A, Ishii E, Egeler RM, Danesino C (1999) Familial clustering of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 107(4):883–888. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01777.x PMID: 10606898

Zheng H, Xia Z, Cao W, Feng Y, Chen S, Li Y-H, Wang D-B (2018) Pediatric Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone: clinical and imaging studies of 27 cases. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 16:72

Ni M, Yang X (2017) Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 13(3):1051–1053

Brown CW, Jarvis JG, Letts M, Carpenter B (2005) Treatment and outcome of vertebral Langerhans cell histiocytosis at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Can J Surg 48:230–236

Bayazit Y, Sirikci A, Bayaram M, Kanlikama M, Demir A, Bakir K (2001) Eosinophilic granuloma of the temporal bone. Auris Nasus Larynx 28(1):99–102

Ginat DT, Johnson DN, Cipriani NA (2016) Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Temporal Bone. Head Neck Pathol. 10(2):209–212

Mayer S, Raggio BS, Master A, Lygizos N (2020) Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Temporal Bone. Ochsner J 20(3):315–318. https://doi.org/10.31486/toj.19.0032 PMID: 33071667; PMCID: PMC7529136

Guo Y, Ning F, Wang G, Li X, Liu J, Yuan Y, Dai P. Retrospective study of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in ear, nose and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(2):102369. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.102369. Epub 2019 Dec 6. PMID: 31870640.

Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL (2018) Langerhans-Cell Histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 379(9):856–868. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1607548 PMID: 30157397; PMCID: PMC6334777

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family for giving consent.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SB. Data curation: AFC. Writing – original draft: AFC and SB. Writing – review and editing: SB, BU and SM. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the parent of the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ocal, F.C.A., Satar, B., Bozlar, U. et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking acute otitis media in childhood—a case presentation. Egypt J Otolaryngol 38, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00303-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00303-0