Abstract

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), quality of life is “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. Researchers have conceptualized quality of life on many levels, and there are multiple views on how it should be defined and measured. Chronic diseases like diabetes mellitus are known to compromise the HRQoL. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease known to affect HRQoL adversely. Two types of tools have been developed to measure HRQoL. Generic tools are general purpose measures used to assess HRQoL of communities and also for comparison between populations. The EQ-5D-5L consists of two pages—the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and the EQ visual analog scale (EQ VAS). The descriptive system comprises the five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression).

Objectives

Assess of quality of life in elderly patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus as well as determine effects of factors related to diabetes and diabetic control on the quality of life of type 2 diabetes.

Methods

- Population of study and disease condition:

◦ A total of 60 participants were enrolled in this study, and all of the participants were among the geriatric group of people (age ≥ 60 years old).

◦ Thirty of them self-reported to have diabetes mellitus type 2, while the other 30 subjects were a control group (self-reported no to have diabetes mellitus).

◦ All participants were subjected to careful history taking, full clinical examination, in addition to laboratory investigation in the form of HBA1C.

◦ All participants had to fill in self-reported questionnaire which is used as a tool for the assessment of HRQOL named EQ-5D-5L (some patients were illiterate so the questionnaire was interviewed to them).

◦ All participants underwent interview questionnaires of the following HRQOL scales: geriatrics depression scale, ADL (activities of daily living scale), and IADL (instrumental activities of daily living scale).

Results

EQ-5D-5L score is significantly higher in diabetic patients than non-diabetics (p value < 0.001).

EQ VAS score is significantly lower in diabetic patients than non-diabetics (p value < 0.001).

ADL (activities of daily living) functional assessment impairment is higher in diabetics than non-diabetics (p value < 0.001).

IADL (independence in activities of daily living) functional assessment impairment is higher in diabetics than non-diabetics (p value < 0.001).

Visual prop is impaired in diabetics more than non-diabetics (p value < 0.001).

Pain severity is mainly affected in diabetics more than non-diabetics.

Conclusion

Type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly patients affects their health-related quality of life and their daily activities.

In our study, the HRQOL of uncontrolled diabetic patients were more negatively affected than that of the controlled diabetic patients.

Moreover, some of our diabetic patients were found to suffer from cognitive disorders (insomnia and depression) as a complication of diabetes.

We also found that the EQ-5D-5L of diabetic patients with comorbidities was higher than those without comorbidities and EQ-VAS was lower in comorbid diabetic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), quality of life is “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [1]. Researchers have conceptualized quality of life on many levels, and there are multiple views on how it should be defined and measured. The health community has generally chosen to focus on the individual-level aspects of quality of life that can be shown to affect physical and mental health. This narrower concept is referred to as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [2].

Chronic diseases like diabetes mellitus are known to compromise the HRQoL. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease known to affect HRQoL adversely [3,4,5,6,7].

Comorbidities like hypertension, other cardiovascular diseases can further compromise the quality of life of diabetic patients [8, 9].

Two types of tools have been developed to measure HRQoL. Generic tools are general purpose measures used to assess HRQoL of communities and also for comparison between populations. Disease-specific tools focus on particular disease and can be useful for assessing treatment effectiveness. WHO BREF [10] and SF 36 [11] are among the widely used generic tools. However, these questionnaires have many questions and thus can be time consuming both for respondents and researchers.

EQ-5D is a standardized measure of health status developed by the EuroQol group in order to provide a simple, generic measure of health for clinical and economic appraisal [12].

The EQ-5D-5L consists of two pages—the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and the EQ Visual Analogue scale (EQ VAS). The descriptive system comprises the five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression). Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. The respondent is asked to indicate his/her health state by ticking (or placing a cross) in the box against the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions. This decision results in a 1-digit number expressing the level selected for that dimension [13, 14].

The digits for five dimensions can be combined in a 5-digit number describing the respondent’s health state. The EQ VAS records the respondent's self-rated health on a 20-cm vertical, visual analog scale with endpoints labeled “the best health you can imagine” and “the worst health you can imagine”. This information can be used as a quantitative measure of health as judged by the individual respondents [14, 15].

Objectives

Assess of quality of life in elderly patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus as well as determine effects of factors related to diabetes and diabetic control on the quality of life of type 2 diabetes.

Methods

-

Population of study and disease condition:

-

A total of 60 participants were enrolled in this study, all of the participants were among the geriatric group of people (age ≥ 60 years old).

-

Thirty of them self-reported to have diabetes mellitus type 2, while the other 30 subjects were a control group (self-reported no to have diabetes mellitus).

-

All participants were subjected to careful history taking, full clinical examination, in addition to laboratory investigation in the form of HBA1C.

-

Diabetic patients had HBA1C ≥ 6.5%, while control group had HBA1C ˂ 5.7%.

-

All participants had to fill in self-reported questionnaire which is used as a tool for the assessment of HRQOL named EQ-5D-5L (some patients were illiterate so the questionnaire was interviewed to them).

-

All participants underwent interview questionnaires of the following HRQOL scales: Geriatric Depression Scale, ADL (activities of daily living scale), and IADL (instrumental activities of daily living scale).

Study location

-

The study were conducted in the Hospital of Internal Medicine, Al Kasr Alainy, Cairo University, as well as internal medicine departments of Ahmad Maher Teaching Hospital.

Inclusion criteria

Patients ≥ 60 years old (males and females).

Patients with type 2 diabetes.

Exclusion criteria

-Patients < 60 years old (males and females)

Methodology in details

This prospective randomized clinical study is approved by the research ethical committee in Cairo University.

Candidates were evaluated as follows:

-

I.

Full history and clinical examination.

-

II.

Routine blood work.

-

III.

HBA1C test.

-

IV.

Tools for assessment of HRQOL we used in the study.

-

V.

Full history and clinical assessment included data regarding the following:

-

1)

History was taken for

-

2)

Age of patients.

-

3)

Previous surgical operations especially abdominal operations.

-

4)

Associated comorbidities such as DM, HTN, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), psychiatric illness, gastritis, thyroid disease, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, liver disease, osteoarthritis, and degenerative joint disease.

-

5)

Social circumstances.

-

6)

Clinical assessment of the patients that included general physical examination, as well as vital signs of the patient and the patient’s

-

7)

Baseline weight in kilogram.

-

8)

Height in meter.

-

9)

Baseline body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2.

Routine blood work in the form of the following:

Complete blood count (CBC) serum sodium and potassium (Na+ and K+) levels, kidney and liver function tests, international normalized ratio (INR), random blood glucose (RBG) level, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test.

Tools used for assessment of HRQOL of the subjects:

A concise, generic measure of self-reported questionnaire that measures health status across different sorts of patients, and diseases.

Overall assessment of their health on a scale from 0 (worst health imaginable) to 100.

Arabic versions of EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS score are available [18].

-

2.

Geriatrics Depression Scale [19]:

-

We used the short form of the scale which consists of 15 questions.

-

Scores of 0–4 are considered normal, while scores of 5 or above indicates depression.

-

Arabic version of Geriatrics Depression Scale is available [18].

-

3.

ADL scale [20]:

-

A score of 6 indicates full function, 4 indicates moderate impairment, and 2 or less indicates severe functional impairment.

-

Arabic version of ADL Scale is available [21].

-

4.

IADL scale [20]:

-

A summary score ranges from 0 (low function, dependent) to 8 (high function, independent).

-

Arabic version of IADL scale is available [21].

Statistical methods

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data was summarized using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies (number of cases) and relative frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were done using unpaired t test when comparing two groups and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons post hoc test when comparing more than two groups [22].

Sample size

Sampling method: convenient sample.

Sample size: 30 patients.

This number of cases was adopted by using MedCalc 19 program, by setting alpha error of 5%, 95% confidence level, and 80% power sample. The sample size for this study calculated from prevalence of good QQL in elderly (51%), according to previous study of Maha Hammam Alshamali et al. [23]. Equations are described in Machin D et al.’s [24] study.

Sample size calculation

Sample size is calculated according to the following formula:

\(n=p\left(1-p\right)\ {\left(\frac{Z}{E}\right)}^2\) [24]

Z = 1.96 (The critical value that divides the central 95% of the Z distribution from the 5% in the tail).

P: prevalence of good QQL in elderly, according to previous study of Maha Hammam Alshamali et al. [23] (= 51%).

E: the desired margin of error (alpha error = 0.05)

Sample size = 30

Results

This work was applied on elderly patients ≥ 60 years with type 2 diabetes attending outpatient clinics and Internal Medicine Departments, Kasr Alainy Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University.

Participants age was ≥ 60 years and males and females were included.

They were divided into two groups:

-

1.

Group 1: including 30 diabetic participants (HBA1C ≥ 6.5%).

-

2.

Group 2: including 30 non-diabetic participants (control, HBA1C ˂ 5.7%).

Quality of life was assessed in our participants by using (EQ-5D-5L, EQ VAS, Geriatric Depression Scale, ADL, and IADL questionnaires.

Arabic versions of our tools were available to our patients.

Description of all study populations

The study included 30 diabetic participants and 30 non-diabetic participants.

Our work included 21 males and 39 females.

As shown in Table 1, the results revealed that

-

Age of the participants ranged from 60 to 76 years.

-

The mean of BMI of our participants was 28.66.

-

The mean of EQ-5D-5L score was 24882.98 and the mean of EQ VAS was 64.33.

As shown in Table 2, we had the following data:

-

We had 12 controlled diabetic patients and 18 not controlled.

-

Thirteen patients received insulin therapies and 17 patients received oral therapies.

-

Twenty patients were compliant to treatment and 10 of them were not compliant.

Comorbidities

The results showed that 44 hypertensive participants, 2 participants had cerebrovascular stroke, 1 was rheumatic heart disease, 1 was heart failure, 1 was ischemic heart disease, 1 was hypothyroid, 4 were hepatic, 10 were CKD, and 1 had Crohnʼs disease.

The study included 36 participants had insomnia and 31 participants had depression according to Geriatric Depression Scale as shown in Table 3.

Comparison between cases and control

When comparing between two groups (as shown in Table 4), we found that

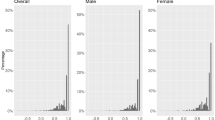

EQ-5D-5L score was significantly higher in diabetic patients than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 1.

EQ VAS score was significantly lower in diabetic patients than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 2.

BMI was significantly higher in diabetic patients than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.009).

As shown in Table 5, our work revealed that diabetic patients had comorbidities more than non-diabetic patients (p value ˂ 0.035).

As shown in Table 6, we concluded the following data:

-

ADL (activities of daily living) functional assessment impairment was higher in diabetics than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 3.

-

IADL (independence in activities of daily living) functional assessment impairment was higher in diabetics than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 4.

-

Visual prop was impaired in diabetics more than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 5.

-

Pain severity was mainly affected in diabetics more than non-diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 6.

EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS scores were not affected by duration of diabetes (p value 0.273 and 0.224 respectively) as shown in Table 7.

As shown in Table 8, the results revealed that EQ-5D-5L score was significantly higher in non-controlled diabetics than controlled diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 7, and EQ VAS score was significantly lower in non-controlled diabetics than controlled diabetics (p value ˂ 0.001) as shown in Fig. 8.

EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS scores were significantly affected by compliance to treatment as non-compliant patients showing higher EQ-5D-5L scores than compliant patients and EQ VAS scores were lower in non-compliant patients than compliant patients (p value ˂ 0.001 and 0.030 respectively) as shown in Table 9, and Figs. 9 and 10).

Discussion

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), quality of life is “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [25].

Researchers have conceptualized quality of life on many levels, and there are multiple views on how it should be defined and measured. The health community has generally chosen to focus on the individual-level aspects of quality of life that can be shown to affect physical and mental health. This narrower concept is referred to as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [26].

In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the quality of life for type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly Egyptian patients. The key findings of this study are the following:

-

A total of 60 elderly patients were enrolled in the study 50% were diabetic and 50% were non-diabetic.

-

A total of 63.3% are diabetic female patients and 36.7% are diabetic male patients.

The main age of our diabetic participants is 65.2 and the mean of BMI is 29.98.

We had 60% uncontrolled diabetic patients and 40% controlled; a total of diabetics 60% had diabetes more than 10 years and 40% less than 10 years.

A total of diabetics 43.3% received insulin therapy and 56.7% received oral therapy, 66.7% compliant to treatment, and 33.3% not compliant to treatment.

The most commonly reported comorbidities in our study were (hypertension 83.3%, chronic kidney diseases 10%, and cerebrovascular stroke 6.7%).

In our study, 53.3% of diabetic patients had insomnia and 53.3% had depression according to Geriatric Depression Scale.

The most common reported problems related to diabetes were visual affection, urine incontinence and frequent fall. A total of our diabetic patients 40% had impaired ADL and 80% had IADL, and 93.3% reported pain and discomfort.

EQ-5D-5L score is significantly higher in non-controlled diabetics than controlled diabetics and EQ VAS score is significantly lower in non-controlled diabetics than controlled diabetics.

EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS scores are significantly affected by compliance to treatment as non-compliant patients showing higher EQ-5D-5L scores than compliant patients and EQ VAS scores are lower in non-compliant patients than in compliant patients.

Our diabetic patients with comorbidities and complications of diabetes had significantly poor health quality of life.

Our results from this study denote that quality of life is significantly differed between different demographic groups based on gender, marital status, education level, and employment status.

Being married, having higher levels of education, exercising regularly, and adhering to prescribed medications were all important factors that positively influenced participants’ quality of life.

Our work is in concurrence with Jankowska A, et al. [27]. This study aimed to develop health-related quality of life (HRQoL) norms for patients with self-reported diabetes, based on a large representative sample of the general Polish population, using the EQ-5D-5L.

Their results suggest respondents with diabetes had a lower EQ VAS score and a lower EQ-5D-5L index score. Also, respondents diagnosed with diabetes but not treated with drugs showed a decrease in EQ VAS scores, but not in the EQ-5D-5L index.

We are also in concurrence with Long E, et al. [28], another study published in 2021. This study aimed to describe and compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among populations with normal glycemic levels, prediabetes, and diabetes in southwest China using EQ-5D-5L INDEX.

The findings of this study suggests that there is a decline of HRQOL of prediabetic patients than non-diabetic, and decline in HRQOL in diabetic patients than the non-diabetics.

The study also revealed that pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression might not be specific for the population with or without diabetes, which is actually in contrast to the results of our study that found a significant relation between pain and discomfort and anxiety and depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly people.

Our results are in concurrence with AbuAlhommos AK, et al. [29]. In their study, diabetes mellitus affected the QoL of the patients to varying degrees. A total of 8.4% of our study sample reported that their disease affected their lives completely and that they did not practice their daily activities at all. In their study, the most common QoL problems were pain and discomfort, followed by movement, depression, and anxiety, and the impact on daily activities and self-care. Moreover, the negative impact on QoL would be if the diabetic patients showed complications.

However, they are in contrast to our results as regards the duration of the disease; we found the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS scores are not affected by the duration of the disease and they found that duration of disease was one of the main factors that significantly affected patients’ QoL in their study.

Conclusion

Type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly patients affects their health-related quality of life and their daily activities.

In our study, the HRQOL of uncontrolled diabetic patients were more negatively affected than that of the controlled diabetic patients.

Moreover, some of our diabetic patients were found to suffer from cognitive disorders (insomnia and depression) as a complication of diabetes.

We also found that the EQ-5D-5L of diabetic patients with comorbidities was higher than those without comorbidities and EQ-VAS was lower in comorbid diabetic patients.

Eventually, type 2 diabetes mellitus affects HRQOL of elderly patients.

However, if diabetes mellitus is controlled, by receiving the proper treatment and regular blood glucose monitoring, HRQOL of elderly diabetic patients would be less affected.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living scale

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CBC:

-

Complete blood count

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DVT:

-

Deep venous thrombosis

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities of daily living scale

- INR:

-

International randomized ratio

- RBG:

-

Random blood glucose

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHOQOL Group (1994) Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798006667

Mielenz T, Jackson E, Currey S et al (2006) Psychometric properties of the centers for disease control and prevention health-related quality of life (CDC HRQOL) items in adults with arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-66

Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Wittenberg E et al (2006) Correlates of health related quality of life in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0249-9

UK. Prospective Diabetes Study Group (1999) Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37). Diabetes Care. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.22.7.1125

Coffey JT, Brandle M, Zhou H et al (2002) Valuing health-related quality of life in diabetes. Diabetes Care

Wee HL, Chueng YB, Li SC et al (2005) The impact of diabetes mellitus and other chronic medical conditions on health-related quality of life: is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? Health Qual Life Outcomes

Koopmanschap M (2002) Coping with type II diabetes: the patient's perspective. Diabetologie.

Maddigan SL, Feeny DH, Johnson JA (2005) Health related quality of life deficits associated with diabetes and comorbidities in a Canadian National Population Health Survey. Qual Life Res

Patel B, Oza B, Patel K et al (2014) Health related quality of life in type-2 diabetic patients in Western India using World Health Organization quality of life – BREF and appraisal of diabetes scale. Int J Diab Dev Ctries

WHOQOL Group (1998) Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med

John E (2000) WareSF-36 health survey update. Spine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-013-0162-y

Last Accessed on 21 Mar 2014. Available from: http://www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-products/eq-5d-3l/self-complete-version-on-paper.html. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4

Yesudian CA, Grepstad M, Visintin E et al (2014) The economic burden of diabetes in India: a review of the literature. Glob Health. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008

Anjana RM, Deepa M, Pradeepa R et al (2017) Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in 15 states of India: results from the ICMR–INDIAB population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al (2011) Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res

Emrani Z, Akbari Sari A, Zeraati H et al (2020) Health-related quality life measured using EQ-5D–5 L: population norms capital Iran. Health Qual Life Outcomes

Brooks R, Boye KS, Slaap B (2020) EQ-5D: plea accurate nomenclature. J Patient-Report Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-020-00222-9

Bekairy AM, Bustami RT, Almotairi M et al (2018) Validity and reliability of the Arabic version of the the EuroQOL (EQ-5D). A study from Saudi Arabia

Yu S, Yang H, Guo X et al (2016) Prevalence depression among rural residents mellitus: cross-sectional study from Northeast China. International journal environmental research. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060542

Edemekong PF, Bomgaars DL, Sukumaran S et al (2021) Activities of daily living. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island

Nasser R, Doumit J (2009) Validity and reliability of the Arabic version of activities of daily living (ADL)

Chan YH (2003) Biostatistics102: Quantitative Data – Parametric & Non-parametric Tests. Singapore Med J 44(8):391–396

Alshamali MH, Makhlouf MM, Rady M, Selim AA, Ismail MFS (2019) Quality of Life and its predictors among Qatari Elderly Attending Primary Health Care Centers in Qatar. https://doi.org/10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93654

Machin D, Campbell MJ, Fayers PM, Pinol APY (2009) Sample size tables for clinical studies, 2nd edn. Blackwell Science Ltd., Berlin, pp 1–315

Memon AB, Rahman AA, Channar KA et al (2021) Assessing the quality of life of oral submucous fibrosis patients: a cross-sectional study using the WHOQOL-BREF tool. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189498

Ruggeri K, Garcia E, Maguire A et al (2020) Health and quality of life outcomes

Jankowska A, Młyńczak K, Golicki D (2021) Validity EQ-5D-5L health-related quality life questionnaire in self-reported diabetes: evidence from general population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01780-2

Long E, Feng S, Zhou L, Chen J (2021) Assessment of health-related quality of life using EuroQoL-5 dimension in populations with prediabetes, diabetes, and normal glycemic levels in Southwest China. Front Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.69011

AbuAlhommos AK , Alturaifi AH, Al-Bin Hamdhah AM, et al. 26 April 2022. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S353525

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Our research was self-funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection were done by BM. Data revision and validation by MA and HR. Data interpretation and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MA and HR. Collection of scientific reviews and data were done by all authors. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

-Protocol titled: Quality of life in elderly people with type 2 diabetes using EQ-5D-5L tool

-Institution: Cairo University

-Decision: APPROVAL

-Date: 14 February 2022

-REC code: MS-666-2021

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AL-Din, M.H., Magdy, B. & Ramadan, H. Quality of life in elderly people with type 2 diabetes using EQ-5D-5L tool: a case control study. Egypt J Intern Med 34, 91 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-022-00177-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-022-00177-x