Abstract

Background

Salmonella typhi infection commonly results in gastroenteritis, bacteremia with or without secondary seeding, or asymptomatic carrier stage. Few cases of Salmonella typhi bacteremia later result in seeding and ultimately lead to further complications including osteomyelitis and rarely vertebral osteomyelitis.

Case presentation

We are discussing a case of a 38-year-old Asian male patient, with no known comorbids. He presented with fever and backache for 4 weeks. Based on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of the spine and positive blood cultures, a diagnosis of XDR Salmonella typhi (S. typhi) osteomyelitis (OM) was made. Patient was started on intravenous therapy as per culture report which was later modified according to treatment response.

Conclusion

S. typhi has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations including osteomyelitis however to the best of our knowledge this is the first reported case of XDR S. typhi vertebral osteomyelitis. We describe the clinical course of the patient and review the literature regarding the treatment of S.typhi vertebral osteomyelitis with a special focus on XDR S. typhi. Treatment course and complications in view of this new resistant strain have to be reported in order to devise general guidelines for the management in such particular cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salmonella typhi infection commonly results in gastroenteritis, bacteremia with or without secondary seeding, or asymptomatic carrier stage [1]. Over the last three decades emerging antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella has become a global concern including the recent epidemic of extensive drug-resistant (XDR) strain in Pakistan [2,3,4]. Most cases infected with the XDR strain of Salmonella typhi result in bacteremia leading to enteric fever with or without complications. Salmonella rarely causes osteomyelitis in the normal host, though few cases have been reported with either pan sensitive or multidrug-resistant S. typhi strain [5, 6]. Treatment of XDR S. typhi is quite challenging. Till now, no research work has been published to define the standard treatment regimen for XDR S. typhi OM. This rendered the treatment of the above-mentioned complication quite challenging.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old Asian gentleman presented to infectious diseases (ID) clinic with the history of fever for 1.5 months. Fever was high grade and continuous but not associated with rigors and chills and had no specific association with mild relieve on taking paracetamol. Patient had no significant medical, surgical and family history. On examination, he only had fever without any other signs and symptoms. Blood cultures were done which were negative with raised leucocyte count of 12.3 × 109/L. He took 7 days of azithromycin and 15 days of cefixime empirically from a general practitioner and his fever eventually subsided.

He remained asymptomatic for a month after which he presented to his general physician (GP) with complaints of fever and back pain. Fever was low grade (Tmax-100 degrees Fahrenheit), and intermittent with evening rise. Backache was severe in intensity resulting in limited mobilityof the patient. On examination, he was afebrile focused examination was performed which showed tenderness at level of L3 and below without any obvious deformity. There was no sensory loss. He was not taking any antibiotics at that time, so for reaching the root cause of backache and fever, MRI was performed.

Investigations

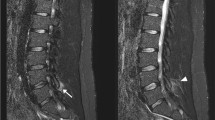

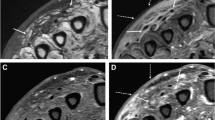

Treatment response in patient was assessed by ESR and CRP trends in accordance to antibiotics introduction and completion (Fig. 1). MRI done from a local government hospital was not of good quality however it showed abnormal signals indicating spinal abscess in L4–L5 extending into the subdural space, resulting in thecal compression, foraminal stenosis, and meningeal enhancement (Fig. 2). A clinical diagnosis of spinal osteomyelitis was made. Other inflammatory tests were also performed including an Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 94 and leukocytosis of 11.6 × 109/L. He was advised for further workup including brucella serology and a blood culture; however, at that time, the patient refused to undergo any invasive tests. Patient’s treatment response was monitored by serial ESR and C-reactive proteins (CRP) (Table 1). A repeat MRI was performed at the end of therapy, which showed improvement (Fig. 3).

Differential diagnosis

Pakistan like other low- and middle-income countries is endemic for tuberculosis and tuberculosis is the most common cause for spinal osteomyelitis [7,8,9,10,11]. Other common differential diagnoses include brucella [8, 12,13,14] and Staphylococcus aureus [15,16,17,18].

Treatment

In view of high ESR and OM, patient was started on empirical anti-tuberculous therapy (ATT). Despite being compliant on ATT for 6 weeks, patient continued experiencing pain and fever and was referred to ID clinic. An ID physician examined him and advised to get his blood cultures, brucella serology, and inflammatory markers (ESR, C-reactive proteins). Patient’s blood cultures with fever spike grew extensive drug-resistant Salmonella typhi (XDR S. Typhi) (sensitive only to azithromycin and carbapenem-meropenem and resistant to ampicillin, ceftriaxone, fluroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol). Eventually, diagnosis of XDR S. Typhi spinal osteomyelitis was made and ATT was stopped.

Patient was started on intravenous (iv) meropenem 1 gm every 8 hourly and azithromycin 1 gm loading dose with maintenance dose of 500 mg once a day for six weeks. Traditionally, the treatment duration of spine OM is usually 4–6 weeks and this duration depends on regular and serial monitoring of patient’s signs and symptoms incorporating both radiological and biochemical investigations.

Patient’s fever spaced out on iv meropenem and azithromycin but pain was still present. ESR and C-reactive proteins (CRP) both declined in response to therapy. After 6 weeks of iv meropenem and iv azithromycin, patient showed improvement in terms of clinical aspect (pain was reduced, range of mobility was increased), radiological assay (Fig. 3—repeat MRI showed improvement) and biochemical laboratory values (declining trend of ESR and CRP). However, he was not completely recovered so the decision was made to prolong the treatment course. In view of lack of any clinical archive or guidelines present, the treatment was modified keeping in view the following aspects: the culture report, usual treatment duration of OM and patient’s request.

Patient opted for all oral therapy so iv meropenem was stopped after 6 weeks and azithromycin was switched to oral formulation. Oral azithromycin was continued for 10 weeks in total and the response to therapy was monitored serially.

Outcome and follow-up

After 10 weeks of therapy, when ESR and CRP were normalized (touched baseline values—Fig. 2) and patient’s condition improved, azithromycin was stopped. Patient was asked for a close follow-up after 10 days. On follow-up, he was doing fine with physiotherapy, his fever resolved, and he returned to his usual light household work. On further follow-up after 2 months, he was still doing well and was able to perform his usual household and professional duties.

Discussion

Salmonella typhi is a gram negative Enterobacteriaceae. It rarely causes osteomyelitis and if it does, it is primarily seen in patients with underlying hemoglobinopathies like sickle cell anemia, or thalassemia. This complication is primarily seen in immune compromised patients, those with an autoimmune disorder, neoplastic diseases, AIDS, on long-term steroids or chemotherapy and people who are in extremes of age [1, 19].

XDR S. typhi is the emerging resistant strain in Pakistan that is resistant to ampicillin, 3rd generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone), fluroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol and sensitive to azithromycin and carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem and ertapenem). The diagnosis and management of XDR S. typhi is challenging. Lack of standardized culture techniques and even basic laboratory equipment makes the diagnosis and treatment very difficult. All these factors result in non-standardized treatment regimen for XDR S. typhi complications especially OM. The local guidelines and research papers throw light on the duration and antibiotics options available for management of complicated and un-complicated bacteremia only [20, 21]. A study done in Pakistan showed out of 81 XDR Typhoid patients, 27% were treated with azithromycin alone, 25% with meropenem alone and 48% received a combination of azithromycin and meropenem [20]. Local guidelines from Pakistan recommends treatment based on clinically stability. The dosage of drugs depends on weight and creatinine clearance of patients. For hemodynamically unstable patient (systolic blood pressure less than 90) dual treatment is advised and duration of treatment recommended is 10–14 days [21].

There are rare cases of spinal OM secondary to S. typhi in immune-competent patients that too with non-XDR Salmonella typhi [22]. None of the local guidelines and published materials include OM treatment regimen and duration. The management strategy is subjective and may vary from person to person. Furthermore, the efficacy of antimicrobials in treating this bug and its complications like osteomyelitis are also lacking. There are no studies available defining the pathogenesis of this complication, its impact on health and rehabilitation. Pathogenesis however seems to be the seeding secondary to bacteremia leading to complications. Extraintestinal manifestations are rare with about 8% cases with enteritis, and gastro-intestinal symptoms and rarely endocarditis, pericarditis and abscess formation. However, osteomyelitis remains rare with only 0.45% of cases presenting with this [23,24,25,26].

In literature so far no cases of vertebral XDR–S. typhi OM have been reported in immune-compromised or healthy individuals. However, there is one case report with spondylitis secondary to XDR-Salmonella paratyphi which was resistant to azithromycin and nalidixic acid, determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS), in a 70-year-old male patient. He presented with backache and fevers and had failure of therapy with azithromycin. Patient responded well to ciprofloxacin and cefotaxime combination as evident by improvement in backache and decline of ESR [27].

There are no guidelines available recommending the duration of treatment in patients with XDR–S. typhi OM, IDSA guidelines on both diarrhea and osteomyelitis deal with non XDR Salmonella infections. Similarly, given the rarity of the disease, there are also no clinical trials to determine the clinical response and the drug regimens to be used in such cases [28, 29].

In our patient with an uncommon manifestation of a particularly resistant organism, treatment was challenging. While a biopsy of the bone for culture is recommended in spinal osteomyelitis for definitive diagnosis, the patient was very reluctant to undergo this and in the presence of the positive blood culture and the subsequent initial response, we opted to continue the therapy as per clinical assessment and inflammatory marker response. Finally, in the absence of clear outcome data we managed him on the lines of a severe XDR S. typhi infection with dual antibiotic therapy. While azithromycin has good bioavailability, we opted to use this intravenously for the first 2 weeks, as anecdotal treatment failures have been seen at our center with initial oral therapy. This might be due to the ongoing inflammation in the intestinal wall. Patient responded well to therapy as the strain was sensitive to azithromycin in contrast to azithromycin resistant strain causing spondylitis.

Our case highlights an unusual manifestation of this new strain of S. typhi that recently emerged as an outbreak in Pakistan [30]. It raised a global concern in February 2018, caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, resistant to first and second-line drugs. We dealt with the challenges associated with the diagnosis and management of this infection in an area endemic for both tuberculosis and S. typhi [29, 30].

Conclusion

Our case highlights an unusual manifestation of this new strain of S. typhi that was recently emerged as an outbreak in Pakistan that raised a global concern in February 2018, caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (Typhi), resistant to first- and second-line drugs [29, 30]. We dealt with the challenges associated with the diagnosis and management of this infection in an area endemic for both tuberculosis and S. typhi. This case report has the following learning points:

-

In view of no established guidelines and randomized control trials for management of XDR S. typhi osteomyelitis, treatment strategy in an endemic region can be directed in view of available/similar case reports [20, 21].

-

Management strategy has to be customized depending upon the severity of disease, available antibiotics, resistance pattern, treatment response, and frequency of visits to ID physician.

-

Our case is a true depiction of above two points and keeping in view of current situation more cases need to be sought and reported for devising future strategic plans.

Availability of data and materials

Data Sharing is not applicable to this study as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study

Abbreviations

- S. typhi :

-

Salmonella typhi

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- XDR:

-

Extended drug-resistant

- OM:

-

Osteomyelitis

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- ATT:

-

Anti-tuberculous therapy

References

Crump JA, Sjolund-Karlsson M, Gordon MA, Parry CM (2015) Epidemiology, clinical presentation, laboratory diagnosis, antimicrobial resistance, and antimicrobial management of invasive Salmonella Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 28(4):901–937

Britto CD, Wong VK, Dougan G, Pollard AJ (2018) A systematic review of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the etiological agent of typhoid. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 12(10):e0006779

Tanmoy AM, Westeel E, De Bruyne K, et al (2021) Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Bangladesh: Exploration of Genomic Diversity and Antimicrobial Resistance. published correction appears in mBio. 12(3):e0104421.

Klemm EJ, Shakoor S, Page AJ, Qamar FN, Judge K, Saeed DK et al (2018) Emergence of an extensively drug-resistant Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi Clone Harboring a Promiscuous Plasmid Encoding Resistance to Fluoroquinolones and Third-Generation Cephalosporins. MBio. 9(6):e02112-18. Published 2018 Nov 13. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02112-18.

Shrestha P, Mohan S, Roy S (2015) Bug on the back: vertebral osteomyelitis secondary to fluoroquinolone resistant Salmonella typhi in an immunocompetent patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2015:bcr2015212503. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212503.

Mathuram A, Rijn RV, Varghese GM (2013) Salmonella typhi rib osteomyelitis with abscess mimicking a ‘cold abscess’. J Glob Infect Dis. 5(2):80–81

Shikhare SN, Singh DR, Shimpi TR, Peh WC (2011) Tuberculous osteomyelitis and spondylodiscitis. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 15(5):446–458. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1293491

Eren Gök S, Kaptanoğlu E, Celikbaş A, Ergönül O, Baykam N, Eroğlu M, Dokuzoğuz B (2014) Vertebral osteomyelitis: clinical features and diagnosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 20(10):1055–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12653

Rauf F, Chaudhry UR, Atif M, ur Rahaman M. (2015) Spinal tuberculosis: Our experience and a review of imaging methods. Neuroradiol J. 28(5):498–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400915609874

Javed G, Laghari AA, Ahmed SI, Madhani S, Shah AA, Najamuddin F, Khawaja R (2018) Development of criteria highly suggestive of spinal tuberculosis. World Neurosurg. 116:e1002–e1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.149

Muhammad T, Baloch NA, Khan A (2015) Management of spinal tuberculosis - a metropolitan city based survey among orthopaedic and neurosurgeons. J Pak Med Assoc. 65(12):1256–1260

Abrantes-Figueiredo J, Wu U (2017) Brucellar vertebral osteomyelitis: a case report and brief review of the literature. Conn Med 81(2):91–94

Baldi PC, Giambartolomei GH (2013) Immunopathology of Brucella infection. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 8(1):18–26

Horasan ES, Colak M, Ersöz G, Uğuz M, Kaya A (2012) Clinical findings of vertebral osteomyelitis: Brucella spp. versus other etiologic agents. Rheumatol Int 32(11):3449–3453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2213-3

Ashong CN, Raheem SA, Hunter AS, Mindru C, Barshes NR (2017) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in foot osteomyelitis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 18(2):143–148. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2016.165

Hatzenbuehler J, Pulling TJ (2011) Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Am Fam Physician 84(9):1027–1033

Aragón-Sánchez J, Lipsky BA (2018) Modern management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. The when, how and why of conservative approaches. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 16(1):35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2018.1417037

Courjon J, Lemaignen A, Ghout I, Therby A, Belmatoug N, Dinh A, Gras G, Bernard L, DTS (Duration of Treatment for Spondylodiscitis) study group (2017) Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis of the elderly: characteristics and outcomes. PLoS One 12(12):e0188470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188470

Tsagris V, Vliora C, Mihelarakis I, Syridou G, Pasparakis D, Lebessi E, Tsolia M (2016) Salmonella Osteomyelitis in previously healthy children: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35(1):116–117. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000937

Qureshi S, Naveed AB, Yousafzai MT, Ahmad K, Ansari S et al (2020) Response of extensively drug resistant Salmonella Typhi to treatment with meropenem and azithromycin, in Pakistan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(10):e0008682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008682

Typhoid Management Guidelines – 2019. https://www.mmidsp.com/typhoid-management-guidelines-2019/

Gill AN, Muller ML, Pavlik DF, Eldredge JD, Johnston JJ, Eickman MM, Dehority W (2017) Nontyphoidal Salmonella osteomyelitis in immunocompetent children without hemoglobinopathies: a case series and systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 36(9):910–912. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001555

Ntalos D, Hennes F, Spiro AS, Priemel M, Rueger JM, Klatte TO (2017) Salmonella osteomyelitis - a rare differential diagnosis of bone tumors. Unfallchirurg. 120(6):527–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-016-0307-9

Cohen JI, Bartlett JA, Corey GR (1987) Extra-intestinal manifestations of salmonella infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 66(5):349–388

Bielke LR, Hargis BM, Latorre JD (2017) Impact of enteric health and mucosal permeability on skeletal health and lameness in poultry. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1033:185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66653-2_9

Anand AJ, Glatt AE (1994) Salmonella osteomyelitis and arthritis in sickle cell disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 24(3):211–221

Park HR, Kim DM, Yun NR, Kim CM (2019) Identifying the mechanism underlying treatment failure for Salmonella Paratyphi A infection using next-generation sequencing - a case report. BMC Infect Dis 19(1):191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3821-x

Berbari EF, Kanj SS et al (2015) 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Native Vertebral Osteomyelitis in Adults. Clin Infect Dis 61(6):e26–e46. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ482

Shane AL, Mody RK (2017) 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clin Infect Diseases 65(12):e45–e80. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix669

Caidi H et al (2019) Emergence of extensively drug-resistant Salmonella Typhi infections among travelers to or from Pakistan - United States, 2016-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 68(1):11–13

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding received for the case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Patient was under care of SFM. Report was written and edited by MI. Supervised by SFM. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved as an exemption by the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of Hospital (Reference # 2019-1977-5059). This study is a retrospective case report and absolutely no personal identifiers were used.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Irshad, M., Mahmood, S.F. Extended drug-resistant Salmonella typhi osteomyelitis: a case report and literature review. Egypt J Intern Med 34, 86 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-022-00173-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-022-00173-1