Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium massiliense is a rapidly growing a non-tuberculous mycobacterium that has been validated as a separate species from the Mycobacterium abscessus group. Only few antibiotics have demonstrated germicidal activity against Mycobacterium massiliense, and some of those include amikacin, clarithromycin, and cefoxitin.

Case presentation

We present the first reported case of near-fatal septic shock caused by disseminated Mycobacterium massiliense after de-clotting of an infected arteriovenous fistula, in a patient with end-stage renal disease with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus infection. Early recognition of the culprit organism and treatment with a combination therapy of clarithromycin and amikacin led to rapid improvement.

Conclusion

This unique case can highlight the importance of taking into consideration Mycobacterium massiliense infection as a cause of arteriovenous fistula thrombosis and highlights the risk of disseminated infection leading to life threatening sepsis upon de-clotting of the fistula.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mycobacteria are broadly categorized into tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Timpe and Runyon further classified non-tuberculous mycobacteria into slow and rapidly growing based on their growth rate [1]. Mycobacterium abscessus complex are a group of rapidly growing mycobacteria commonly found in soil and water and are well known to be multidrug-resistant [2]. Mycobacterium massiliense was identified previously as subspecies of Mycobacterium abscessus based on an identical 16S rRNA sequence but was validated as a separate species from the Mycobacterium abscessus group in 2004 due to differences in hsp65 and sodA gene sequences [3]. Mycobacterium massiliense is capable of causing human infections, usually skin and soft tissue infection after trauma and post procedural infections. We present the first reported case of Mycobacterium massiliense infection of an arteriovenous fistula with subsequent life-threatening bacteremia after de-clotting, in a patient with end-stage renal disease and human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Case presentation

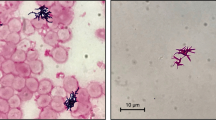

A 70-year-old male patient with past medical history of untreated human immunodeficiency virus infection and end-stage renal disease was admitted to the hospital after missing scheduled hemodialysis session attributed to a malfunctioning arteriovenous fistula. The patient denied pain at the fistula site, fever, or chills. Initial vital signs were stable and lab work was unremarkable besides elevated blood, urea, nitrogen, and creatinine due to missed hemodialysis. Cluster of differentiation-4 count was 557. Examination of the left arm revealed an arteriovenous fistula without a palpable thrill or an audible bruit and no surrounding erythema, swelling, or discharge. Duplex ultrasound suggested arteriovenous fistula thrombosis. The patient subsequently underwent successful de-clotting of the arteriovenous fistula under radiologic guidance. On post-op day 2, the patient developed symptoms of septic shock including symptomatic bradycardia and hypotension, necessitating transfer to the intensive care unit and transcutaneous pacing and vasopressor support. Vancomycin (15 mg/kg/intravenous dose every 12 h) and cefepime (2 g/intravenous dose every 12 h) were used as an empiric therapy for septic shock. Complete blood count showed total leukocyte count of 4340 cells/mm3. Transesophageal echocardiogram was negative for valvular vegetations or abscess. Hemodialysis was continued via a centrally placed intravenous line. Subsequently, three consecutive blood cultures and one culture drawn from the arteriovenous fistula site were positive for acid fast bacilli, which was reported as Mycobacterium abscessus. Chest radiograph did not reveal any pulmonary infiltrates or cavitary lesions. The patient did not report a prior history of pulmonary or extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Interferon gamma release assay was negative. This prompted discontinuation of vancomycin (15 mg/kg/intravenous dose every 12 h) and cefepime (2 g/intravenous dose every 12 h) and initiation of intravenous amikacin (10–15 mg/kg/day) and clarithromycin (1000 mg/day) as anti-mycobacterial therapy. The isolates showed susceptibly to clarithromycin (1000 mg/day) (minimum inhibitory concentration 90 < 1 μg/dl) and amikacin (10–15 mg/kg/day) (minimum inhibitory concentration 90 = 3 μg/dl); hence, the same regimen was continued. Transcutaneous pacing was discontinued, and vasopressors were successfully weaned off gradually after initiation of antimycobacterial therapy. Follow-up blood cultures drawn after the initiation of antibiotics showed no growth. Further genetic testing of the isolates revealed the acid fast bacilli to be Mycobacterium massiliense. The underlying focus of bacteremia was likely the arteriovenous fistula with bacteremia precipitated during de-clotting. The central intravenous access was discontinued, and hemodialysis through the arteriovenous fistula was resumed. The patient was discharged home to complete 4 weeks of clarithromycin (1000 mg/day) and amikacin (10–15 mg/kg/day) therapy. He continued to follow-up with infectious disease physician and repeat blood cultures and cultures from the arteriovenous fistula site remained negative.

Discussion

Mycobacterium massiliense has previously been linked with bronchiectatic pulmonary disease [4], cutaneous disease [5], and pacemaker pocket infection, intramuscular injections, and post-video surgical infections [3, 6,7,8,9]. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria are generally associated with infection in immunodeficiency states such as human immune deficiency virus, genetic mutations in the synthesis of interferon gamma and interleukin-12, and other conditions such as bronchiectasis, peculiar body habitus such as pectus excavatum, scoliosis, and mitral valve prolapse [10,11,12,13]. Arteriovenous fistula thrombosis secondary to Mycobacterium tuberculosis [14] and arteriovenous graft infection secondary to Mycobacterium abscessus [15] has previously been reported. Although non-tuberculous mycobacteria bacteremia is rare in dialysis access-related infections, delayed identification of these organisms may result in poor clinical outcomes [10]. Our case identifies Mycobacterium massiliense infection as a cause of arteriovenous fistula thrombosis and highlights the risk of disseminated infection leading to life-threatening sepsis upon de-clotting of the fistula. The case also demonstrates the importance of keeping a low threshold of suspicion for non-tuberculous mycobacteremia with Mycobacterium massiliense in patients with an immunocompromised state. Treatment options are limited as there are only a few antibiotics which have demonstrated in vitro activity against Mycobacterium massiliense. Cordoso et al. [16] studied antimicrobial susceptibility of Mycobacterium massiliense recovered from wound samples of patients submitted to arthroscopic and laparoscopic surgeries. The isolates showed susceptibility to amikacin and clarithromycin but resistance to ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, sulfamethoxazole, and tobramycin and an intermediate profile to cefoxitin. Koh et al. compared treatment outcomes of patients infected with either Mycobacterium abscessus or Mycobacterium massiliense. Standardized combination antibiotic therapy, including a clarithromycin-containing regimen in combination with an initial 4-week course of cefoxitin and amikacin, was given to 57 patients (24 with Mycobacterium abscessus and 33 with Mycobacterium massiliense) for more than 12 months. The proportion of patients with sputum conversion and maintenance of negative sputum cultures was higher in patients with Mycobacterium massiliense infection (88%) than in those with Mycobacterium abscessus infection [17]. Clarithromycin has been indicated as the first-line drug of choice for the treatment of infections caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria and is even more appropriate for Mycobacterium massiliense. Due to the small risk of resistance development, it is recommended to use a second drug like amikacin in the treatment for such infections initially, especially in an unstable patient. Antibiotic susceptibility testing of all the isolates is strongly recommended to ensure complete eradication. Another study by Koh et al. [18] revealed that oral macrolide therapy after an initial 2-week course of combination antibiotics might be effective in most patients with Mycobacterium massiliense lung disease. Hence, once the patient is stable, treatment can be deescalated to clarithromycin monotherapy. In case of presence of foreign objects in body, such as breast implants or percutaneous catheters, every effort should be made to remove them for the prevention of recurrence. Once the cultures turn negative and the patient is vitally stable, an oral regimen for four or more weeks can be considered [18]. For serious disease, a minimum of 4 months of therapy is recommended to achieve cure; for bone infections, it is 6 months. Noncompliance can lead to ineffective elimination and recurrent bacteremia.

Conclusion

In essence, we have presented the first reported case of near-fatal septic shock caused by disseminated Mycobacterium massiliense after de-clotting of an infected arteriovenous fistula, in a patient with end-stage renal disease with concomitant human immunodeficiency virus infection. This unique case can highlight the importance of taking into consideration Mycobacterium massiliense infection as a cause of arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, as well as highlight the risk of disseminated infection leading to life threatening sepsis upon de-clotting of the fistula.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to HIPAA but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, if permissible by patient.

References

Runyon EH (1959) Anonymous mycobacteria in pulmonary disease. Med Clin N Am 43:273–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(16)34193-1

Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ Jr (2002) Clinical and taxonomic status of pathogenic nonpigmented or late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 15(4):716–746. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.15.4.716-746.2002

Adékambi T, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Greub G et al (2004) Amoebal coculture of “Mycobacterium massiliense” sp. nov. from the sputum of a patient with hemoptoic pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 42(12):5493–5501

Koh W-J, Jeon K, Shin SJ (2013) Successful treatment of Mycobacterium massiliense lung disease with oral antibiotics only. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02016-12

Cho AY, Kim YS, Kook YH, Kim SO, Back SJ, Seo YJ, Lee JH, Lee Y (2010) Identification of cutaneous Mycobacterium massiliense infections associated with repeated surgical procedures. Ann Dermatol 22(1):114–118. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2010.22.1.114

Cardoso AM, Martins de Sousa E, Viana-Niero C, Bonfim de Bortoli F, Pereira das Neves ZC, Leão SC, Junqueira-Kipnis AP, Kipnis A (2008) Emergence of nosocomial Mycobacterium massiliense infection in Goiás, Brazil. Microbes Infect 10(14-15):1552–1557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2008.09.008

Duarte RS, Lourenço MCS, Fonseca LDS et al (2009) Epidemic of postsurgical infections caused by Mycobacterium massiliense. J Clin Microbiol 47(7):2149–2155. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00027-09

Kim HY, Yun YJ, Park CG, Lee DH, Cho YK, Park BJ, Joo SI, Kim EC, Hur YJ, Kim BJ, Kook YH (2007) Outbreak of Mycobacterium massiliense infection associated with intramuscular injections. J Clin Microbiol 45(9):3127–3130. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00608-07

Simmon KE, Pounder JI, Greene JN, Walsh F, Anderson CM, Cohen S, Petti CA (2007) Identification of an emerging pathogen, Mycobacterium massiliense, by rpoB sequencing of clinical isolates collected in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 45(6):1978–1980. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00563-07

American Thoracic Society (1987) Mycobacterioses and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Joint Position Paper of the American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control. Am Rev Respir Dis 136:492. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/136.2.492

Dorman SE, Holland SM (2000) Interferon-gamma and interleukin-12 pathway defects and human disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 11:321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6101(00)00010-1

Casanova JL, Abel L (2002) Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Annu Rev Immunol 20:581–620. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081501.125851

Iseman MD, Buschman DL, Ackerson LM (1991) Pectus excavatum and scoliosis: thoracic anomalies associated with pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Am Rev Respir Dis 144:914. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.914

Rosado-Canto R, Martínez-Benítez B, Carrillo-Pérez DL, Morales-Buenrostro LE (2017) Arteriovenous fistula thrombosis with mycobacterial infection. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.008

Kang KP, Jeon BJ, Lee CS, Lee TH, Lee S, Kim S et al (2009) Arteriovenous graft infection caused by Mycobacterium abscessus in a hemodialysis patient. Clin Neophrol 71(04):465–466. https://doi.org/10.5414/CNP71465

Cardoso AM, Junqueira-Kipnis AP, Kipnis A (2011) In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Mycobacterium massiliense recovered from wound samples of patients submitted to arthroscopic and laparoscopic surgeries. Minim Invasive Surg 724635:4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/724635

Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee SH, Park YK, Kim CK, Shin SJ, Huitt GA, Daley CL, Kwon OJ (2011) Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183(3):405–410. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201003-0395OC Epub 2010 Sep 10

Koh WJ, Jeong BH, Jeon K, Kim SY, Park KU, Park HY, Huh HJ, Ki CS, Lee NY, Lee SH, Kim CK, Daley CL, Shin SJ, Kim H, Kwon OJ (2016) Oral Macrolide therapy following short-term combination antibiotic treatment of mycobacterium massiliense lung disease. Chest. 150(6):1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.003 Epub 2016 May 7

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“WM” was a major contributor in the writing of the manuscript. Dr. “HN” oversaw the patient with the attending physician and contributed to the editing of the paper. “A.A.C” helped with the interpretation of the patient data. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved informed consent

Consent for publication

Approved informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nawaz, H., Choudhry, A.A. & Morse, W. Case report of a near-fatal case of Mycobacterium massiliense sepsis after de-clotting of an arteriovenous fistula. Egypt J Intern Med 33, 39 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00069-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00069-6