Abstract

Introduction

Clinical trials are regarded as the gold standard evidence for establishing the effectiveness and efficacy of different therapeutic strategies. LBP is a globally prevalent health symptom that is commonly encountered clinically by the physiotherapist. Physiotherapeutic strategies are essential in managing individuals with low back pain (LBP). High-quality clinical trials are required to establish the efficacy/effectiveness of physiotherapeutic management strategies. A clinical trial’s generalizability depends on various factors such as geographical location, population, and healthcare facilities. Evaluating the publication trends and quality of clinical trials conducted by Indian physiotherapists will help determine the effectiveness of physiotherapeutic strategies in managing LBP with respect to the Indian context. Therefore, the study aimed to assess the publication trends and quality of clinical trials conducted by Indian physiotherapists.

Methods

The authors used MEDLINE and the PEDro database to screen for eligible trials. The research encompassed clinical trials addressing low back pain that were authored by Indian physiotherapists and were published between January 2005 and December 2021. The included studies were analyzed for quality using the PEDro Scale. The authors also evaluated sample size calculation, trial registration status, and adherence to the CONSORT checklist.

Results

A total of 866 studies were screened, of which 37 studies were included for final analysis. Most of the studies were published in the southern states of India (Maharashtra and Karnataka), and most were published in 2019. Methodological quality evaluation by PEDro yielded a mean score of 5.17 (range, 2–9). The major missing elements from PEDro items were blinding and intention to treat analysis. Sample size calculation was not found in 83.7% of the studies. Trial registrations were reported in only 10.8% of the studies, and the trials did not report adherence to standard guidelines such as CONSORT.

Conclusion

Included studies showed poor to fair methodological quality according to the PEDro Scale. There has been an increase in the number of RCTs published by Indian physiotherapists. However, there is significant room for improvement in the conduct and reporting of trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is vital in enhancing healthcare quality and improving patient outcomes [1, 2]. EBP can be a solution for various clinical practice conundrums, with clinical trials acting as a source of deciding the efficacy of interventions [3, 4]. Clinicians are advised to base their treatment decisions on clinical trials that have good research validity. Patients, physicians, and policymakers rely heavily on the knowledge gained from high-quality clinical trials to make appropriate evidence-based healthcare decisions. Consequently, it is imperative to have well-designed methodological studies as the foundation for making sound clinical decisions.

Low back pain (LBP) is the modern world health enigma. There has been an evolution in our understanding and management of LBP. This change has been possible because of the vast volume of research conducted on LBP. The first randomized controlled trial (RCT) of physical intervention (manipulation and physiotherapy) on LBP was published around 1975 [5]. Since then, growth in the number of trials of interventions addressing back pain has been exponential. A simple search of PubMed reveals that there are around 3497 RCTs that have been conducted on LBP since 1975.

Physiotherapy is considered a vital healthcare profession in terms of LBP care. Physiotherapists are at the forefront of LBP care and can be influential in providing practical, affordable, and safe rehabilitation [6]. Over the last decade, a transition has been seen in the physiotherapy profession toward evidence-based care [7, 8]. With this shift taking place toward EBP, physiotherapists in the future will make clinical decisions based on the current best available research [4]. Along with developing the evidence-based model, extensive research has been produced to create a knowledge base on which the practice and profession can grow.

The number of trials assessing physiotherapeutic management strategies for LBP has grown and is expected to continue increasing. This surge is attributed to the ongoing reform in physiotherapy education, transitioning from diploma vocational courses to university-based baccalaureate, postbaccalaureate degrees, and doctorate programs [9]. Alongside this, there have been advances in physiotherapist training, developments in clinical trial design, and reporting of clinical trials [10]. Even though the number of clinical trials related to the effectiveness and efficacy of different physiotherapeutic management strategies increased considerably over the years, the methodological quality and statistical reporting of these studies have slowly improved [11].

Customizing clinical trials for specific populations is crucial due to variations in study methodologies and contextual factors, posing challenges to generalization [12]. Additionally, the research output is influenced by the country’s research environment and the availability of resources and funding. Besides, there is a dearth of evidence concerning LBP from lower-middle-income countries [6]. Considering these aspects, the authors assessed the publication trends and the quality of the trials published from the Indian subcontinent, as it is imperative to critically appraise the results of clinical trials for their rigor, reliability, and validity.

Therefore, the study’s objective was to examine the publication trend and quality of clinical trials on back pain conducted by Indian physiotherapists.

Materials and methods

The first step in conducting this study was a review of existing literature based on the set eligibility criteria. The study followed three basic steps: (1) identify intervention-based studies related to LBP conducted by Indian physiotherapy researchers in the selected databases, (2) summarize and analyze the studies according to the PICO (problem, intervention, comparator, outcomes) format, and (3) analyze the methodological rigor. The search strategy of the study was guided by the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [13].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if (a) they had assessed treatment efficacy/effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for low back pain (clinical trials) and were done in an Indian setting with at least one of the investigators being a physiotherapist; (b) they must be published in the English language. Studies were excluded if (a) they involved animals as subjects, (b) they were published in any other language than English, and (c) they assessed interventions that are not directly related to physiotherapy for low back pain were omitted to maintain the review’s focus. If the study’s full text is unavailable online, an attempt to contact the corresponding author was made, and if unsuccessful, the study was excluded.

Literature search

An online literature search was conducted utilizing MEDLINE and PEDro databases from January 2005 to December 2021. The search strategy was created and executed by SQ, and it is highlighted in Additional file 1: Appendix A.

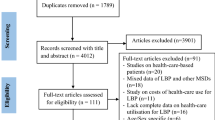

Study selection

All identified records were collated and uploaded to Mendeley reference manager software after the search. Duplicates were deleted, and appraisal of all titles was performed independently by two authors (AS) and (SQ) after the initial online literature search. Following this, all potentially relevant full‐text articles were retrieved and screened for inclusion in the final analysis, and any discrepancy was resolved through discussion. The study selection result is highlighted in a flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

Each study’s data and findings was extracted using a standardized PICO (population, treatment, comparison, and outcome) format. Both authors extracted data combined, and any discrepancies were removed after discussion. The extracted information was as follows: (a) the author’s name and year of publication; (b) intervention duration of the study; (c) information on the population, intervention, comparators, and outcomes; (d) methodology, including the type of intervention, follow up of the patients involved in the trials, sample size calculation, CTRI registration, and CONSORT flow diagram; and (e) the state of India where the study was conducted.

Methodological quality tool

PEDro Scale was used to evaluate methodological quality within individual studies. The scale is based on the Delphi list developed by Verhagen and colleagues at the Department of Epidemiology, University of Maastricht [14]. The scale consists of 11 items, out of which item 1 relates to the external validity (or “generalizability” or “applicability” of the trial), items 2–9 evaluate the internal validity, and items 10–11 assess the statistical information with criteria 1 not to be considered in the final score. Items are rated yes or no (1 or 0), whether the criterion is satisfied or not in the study. A total PEDro score is achieved by adding items 2 to 11 ratings for a combined total score between 0 to 10.

The reliability of ratings of PEDro scale items has been reported to be from “fair” to “substantial,” and the reliability of the total PEDro score as “fair” to “good [15].” Morton et al. report the PEDro scale as a valid measure for assessing the methodological quality of clinical trials [16]. Previously published literature says that total PEDro scores of 0–3 are considered “poor,” 4–5 “fair,” 6–8 “good,” and 9–10 “excellent”; however, it is critical to note that these categories have not been validated [17]. The methodological quality using PEDro was assessed by the primary author (AS).

Results

Database searches on MEDLINE and PEDro generated 866 independent study titles, resulting in 846 titles after removing duplicates. After a title and abstract search, 794 studies were removed because they did not meet the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). The authors conducted a search and obtained the chosen 54 articles. However, six of these articles were not retrieved, despite attempts to contact the authors via email. In the end, 37 studies underwent critical appraisal. Additional file 1: Appendix B summarizes the included studies with a specific focus on population, intervention, and outcome measures.

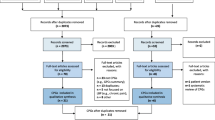

The region of India where the study was conducted was also identified. Additionally, the majority of the studies were done in Maharashtra (9), followed by Karnataka (8) and Uttar Pradesh (4); in contrast, there were no studies from various other states of India; Fig. 2 illustrates the number of studies from specific states and union territories. Most of the selected studies were published in 2019 (eight studies), while six were published in 2020 (Fig. 3).

Methodological quality

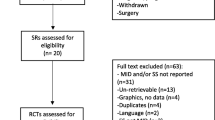

The PEDro score for included studies ranged from 2 to 9, with a median PEDro score of 5 for 36 studies out of 37. We did not rate one study as it was not an RCT. Categorization of the RCTs according to the total PEDro score revealed four studies as “poor,” 16 studies as “fair,” 15 studies as “good,” and one study as “excellent.” The total scores from the PEDro scale and the individual item scores are featured in Additional file 1: Appendix C, while Table 1 showcases the aggregated total scores. Individual PEDro scale items satisfied by 36 trials are highlighted in Fig. 4.

Most of the included studies did not take long-term follow-ups, and only 29.7% (n = 11) of the studies mentioned it. Sample size calculation was missing from 83.8% (n = 31) of studies. Similarly, trial registration was mentioned by merely 10.8% (n = 4) studies, while the CONSORT flow diagram was illustrated by a meager 32.4% of studies (Table 1).

Discussion

In terms of growth in the number of trials from the first study published in 2009, there has been a gradual increase in the number of RCTs related to LBP, with a steep decrease after 2020. This can be attributed to the COVID-19 outbreak in India, after which there was a challenge in conducting clinical trials. Comparing the research output with other similar countries, the number of trials (related to LBP) published by Indian physiotherapists is more than in Argentina while far less than in other developing countries such as Brazil (according to the ranking of the website http://www.expertscape.com/), this may be attributed to different reasons such as low research funding, and the fact that musculoskeletal disorders are not a primary health concern [55].

The rise in the number of studies originating from the Southern region can be attributed to the expansion of physiotherapy training institutions and the introduction of PhD programs approximately a decade ago. There is a substantial disproportion in research production, with India’s Western and Eastern regions having almost no contributions. Because India is a distinct subcontinent with a diverse culture and people with different rehabilitation needs, studies conducted in one region may not necessarily be generalized to other parts. In the future, we need research representations from other parts of the country.

The critical appraisal of the included studies highlights the need to develop more rigorous intervention trials. The methodological quality assessment through PEDro showed that the quality of studies had vast variations; it ranged from poor to good, and only one study was found to be excellent. Assessment of quality on the PEDro scale revealed a few methodological elements that must be addressed to develop studies with better internal validity and less bias risk.

RCTs (Randomized controlled trials) are considered the most significant research design for objectively assessing the impact of novel treatments; however, randomization is inadequately executed and reported [56]. The findings of our assessment report show that only 22% of the studies included had described allocation concealment (Fig. 4), which we believe could be a definite source of selection bias. The other parameter broadly missing among the studies was blinding/masking. Consciously omitting it when it is possible within the constraints of the trial designs may introduce human expectations in the trial and hence reduce the reliability of the results stated. In some trials, the eligibility criteria were missing, limiting the study’s generalizability and hindering the translation of the findings to the real world.

In addition to PEDro, the intervention durations employed in the trials were also assessed. The study durations had wide variations ranging from 1 day to 8 weeks. Most of the studies evaluated short-term or immediate effects of therapies on change in pain, range, and qualitative or quantitative elements, even though the patient population of the studies was nonspecific chronic LBP. It has been previously stated that evidence relating to the immediate effects of interventions that gauge clinical response may not be of much use when making long-term, progressive clinical decisions [57]. Long-term follow-ups were also missing from the trials, and this may be due to several reasons, with lack of funds being a significant factor.

Sample size estimation is one of the founding steps in designing a clinical trial to answer the research question; this was missing in most of the included studies. It is evident from the literature that underpowered research may prove that a beneficial treatment is of no value (“false negative” or Type II error) [58]. Trials must be large enough to have a high probability (or “power”) so that they can find an actual clinically significant difference between groups.

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) issued a guideline in 2004 recommending that any clinical study submitted for publication be registered in a publicly available clinical trial register [59]. In India, “The Clinical Trials Registry—India (CTRI),” hosted at the ICMR’s National Institute of Medical Statistics, started trial registration on 15th June 2009 [60]. Afterward, it became mandatory for the trials to get a prospective registration. During our analysis, only four studies had prospective CTRI registrations. Lack of registrations has been linked to a high risk of bias among trials [61]. Trial registrations ensure openness, which is essential for the research community (funders, academics, publishers, regulators, and others) to be held accountable and for patients and the general public to be aware of what research has occurred and is now underway [62].

In the scientific community, there is always an argument over putting research into practice. This may result from a lack of clarity and trustworthiness toward the trials being published. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 guideline was aimed at improving the reporting of RCTs, allowing readers to appreciate a trial’s design, conduct, analysis, and interpretation and judge the validity of its results. Adherence to the CONSORT was missing in the included studies (Table 1). This absence of adherence may contribute to reporting bias and lead to a lack of transparency and reproducibility of the trial [63].

The study findings may be limited as only two databases were selected for identification of the clinical trials. However, Medline covers all journals recognized as core journals that publish clinical trials of physiotherapy interventions, while the PEDro is a dedicated free database for over 60,000 physiotherapy clinical trials.

Recommendations for designing better RCTs

The critical appraisal highlights key loopholes that must be addressed by researchers in the future to produce more reliable and valid intervention studies. The focus should not only be laid on increasing the methodological quality but also on the innovations that can be incorporated into back pain research. As identified in Additional file 1: Appendix A, most trials evaluated the effect of either some form of core strengthening or focused on manual therapy. There was a lack of diversity in the interventions assessed, which may limit the evidence-based treatment approaches available for Indian physiotherapists. Despite the recent evolution of pain science and research, there is an absence of exploration in this area. The common recommendations are highlighted in Fig. 5; these are generated based on the critical points identified and may aid in designing future RCTs [64].

Implications for Physiotherapy research

The critical appraisal of the included studies reveals notable deficiencies in methodological quality and diversity. To address these gaps, physiotherapy researchers in India should prioritize studies with enhanced internal and external validity. The literature highlights the positive correlation between evidence-based practice and improved treatment outcomes. Therefore, it becomes imperative for Indian physiotherapists to engage in robust and high-quality research, as this will contribute to advancing knowledge and fostering evidence-based practices. Such an approach holds the potential for far-reaching implications, significantly influencing the standards and effectiveness of physiotherapy practice throughout India. Emphasizing and fostering a research culture within the physiotherapy community will undoubtedly contribute to elevated standards of care and positively impact the overall quality of physiotherapy services in the country.

Conclusion

The main finding of the study is that the included studies had poor to fair methodological quality. Major methodological flaws were detected, such as a lack of sample size calculations (underpowered studies) and an absence of clarity while reporting and publishing the trials. The PEDro scores draw attention to the absence of parameters that may have bound the trials to have reduced internal validity.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- NPRS:

-

Numeric pain rating scale

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disability Index

- MODI:

-

Modified Oswestry Disability Index

- MMT:

-

Manual muscle testing

- SEBT:

-

Star excursion balance test

- MET:

-

Muscle energy technique

- PRT:

-

Positional release technique

References

Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18:385–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2008.028043.

Ramírez-Morera A, Tristan M, Vazquez JC. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in cardiovascular health care quality improvements: a systematic review. F1000Research. 2019;8:1–22.

Sibbald B, Roland M. Why are randomised controlled trials important? Br Med J. 1998;316:201.

Fetters L, Tilson J. Evidence based physical therapy. FA Davis. 2018.

Doran DML, Newell DJ. Manipulation in treatment of low back pain: a multicentre study. Br Med J. 1975;2:161–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.5964.161.

Sharma S, McAuley JH. Low back pain in low- and middle-income countries, part 1: the problem. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2022;52:233–5. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.11145.

Scurlock-Evans L, Upton P, Upton D. Evidence-based practice in physiotherapy: a systematic review of barriers, enablers and interventions. Physiother (United Kingdom). 2014;100:208–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.03.001.

Hush JM, Alison JA. Evidence-based practice: lost in translation? J Physiother. 2011;57:143–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70034-0.

Physiopedia. Physiotherapy in India n.d. https://www.physio-pedia.com/India (accessed February 2, 2022).

Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Sherrington C, Elkins MR. Reported quality of randomized controlled trials of physiotherapy interventions has improved over time. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.009.

Geha NN, Moseley AM, Elkins MR, Chiavegato LD, Shiwa SR, Costa LOP. The quality and reporting of randomized trials in cardiothoracic physical therapy could be substantially improved. Respir Care. 2013;58:1899–906. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02379.

Hariohm K, Prakash V, Saravankumar J. Quantity and quality of randomized controlled trials published by Indian physiotherapists. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6:91. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.154007.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Verhagen AP, De Vet HCW, De Bie RA, Kessels AGH, Boers M, Bouter LM, et al. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1235–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00131-0.

Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2003;83:713–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/83.8.713.

de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55:129–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(09)70043-1.

Cashin AG, McAuley JH. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J Physiother. 2020;66:59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.005.

Bhadauria EA, Gurudut P. Comparative effectiveness of lumbar stabilization, dynamic strengthening, and pilates on chronic low back pain: randomized clinical trial. J Exerc Rehabil. 2017;13:477–85. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.1734972.486.

Kumar T, Kumar S, Nezamuddin M, Sharma VP. Efficacy of core muscle strengthening exercise in chronic low back pain patients. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2015;28:699–707. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-140572.

Chhabra HS, Sharma S, Verma S. Smartphone app in self-management of chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:2862–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5788-5.

Ali MN, Sethi K, Noohu MM. Comparison of two mobilization techniques in management of chronic non-specific low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2019;23:918–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.02.020.

Nambi G, Kamal W, Es S, Joshi S, Trivedi P. Spinal manipulation plus laser therapy versus laser therapy alone in the treatment of chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;54:880–9. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.18.05005-0.

Satpute K, Hall T, Bisen R, Lokhande P. The effect of spinal mobilization with leg movement in patients with lumbar radiculopathy—a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:828–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.11.004.

Majeed S, Ts A, Sugunan A, Ms A. The effectiveness of a simplified core stabilization program (TRICCS - Trivandrum Community-based Core Stabilisation) for community-based intervention in chronic non-specific low back pain. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1131-z.

Divya, Parveen A, Nuhmani S, Ejaz Hussain M, Hussain KM. Effect of lumbar stabilization exercises and thoracic mobilization with strengthening exercises on pain level, thoracic kyphosis, and functional disability in chronic low back pain. J Complement Integr Med. 2021;18:419–24. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2019-0327.

Ganesh S, Chhabra D, Kumari N. The effectiveness of rehabilitation on pain-free farming in agriculture workers with low back pain in India. Work. 2016;55:399–411. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162403.

Muthukrishnan R, Shenoy SD, Jaspal SS, Nellikunja S, Fernandes S. The differential effects of core stabilization exercise regime and conventional physiotherapy regime on postural control parameters during perturbation in patients with movement and control impairment chronic low back pain. Sport Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2555-2-13.

Kumar S, Sharma VP, Aggarwal A, Shukla R, Dev R. Effect of dynamic muscular stabilization technique on low back pain of different durations. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2012;25:73–9. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2012-0312.

Tambekar N, Sabnis S, Phadke A, Bedekar N. Effect of Butler’s neural tissue mobilization and Mulligan’s bent leg raise on pain and straight leg raise in patients of low back ache. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20:280–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.08.003.

Babina R, Mohanty PP, Pattnaik M. Effect of thoracic mobilization on respiratory parameters in chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2016;29:587–95. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-160679.

Patel VD, Eapen C, Ceepee Z, Kamath R. Effect of muscle energy technique with and without strain-counterstrain technique in acute low back pain-a randomized clinical trial. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2018;38:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1013702518500051.

Shah SG, Kage V. Effect of seven sessions of posterior-to-anterior spinal mobilisation versus prone press-ups in non-specific low back pain-randomized clinical trial. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2016;10:10–3. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/15898.7485.

Vignesh Bhat P, Patel VD, Eapen C, Shenoy M, Milanese S. Myofascial release versus Mulligan sustained natural apophyseal glides’ immediate and short-term effects on pain, function, and mobility in non-specific low back pain. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10706. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10706.

Nagrale AV, Patil SP, Gandhi RA, Learman K. Effect of slump stretching versus lumbar mobilization with exercise in subjects with non-radicular low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618611Y.0000000015.

Ganesh GS, Chhabra D, Pattnaik M, Mohanty P, Patel R, Mrityunjay K. Effect of trunk muscles training using a star excursion balance test grid on strength, endurance and disability in persons with chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2015;28:521–30. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-140551.

Kumar SP. Efficacy of segmental stabilization exercise for lumbar segmental instability in patients with mechanical low back pain: a randomized placebo controlled crossover study. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:456–61. https://doi.org/10.4297/najms.2011.3456.

Ajimsha MS, Daniel B, Chithra S. Effectiveness of myofascial release in the management of chronic low back pain in nursing professionals. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2014;18:273–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.05.007.

Kumar S, Sharma VP, Shukla R, Dev R. Comparative efficacy of two multimodal treatments on male and female sub-groups with low back pain (part II). J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2010;23:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2010-0241.

Kumar S, Negi MPS, Sharma VP, Shukla R, Dev R, Mishra UK. Efficacy of two multimodal treatments on physical strength of occupationally subgrouped male with low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22:179–88. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2009-0234.

Kumar S, Sharma VP, Negi MPS. Efficacy of dynamic muscular stabilization techniques (DMST) over conventional techniques in rehabilitation of chronic low back pain. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:2651–9. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3dde0.

Sarker KK, Sethi J, Mohanty U. Effect of spinal manipulation on pain sensitivity, postural sway, and health related quality of life among patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2019;13:1–5. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2019/38074.12578.

Ku DK. Effect of expiratory training and inspiratory training with lumbar stabilization in low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev. 2020;11:236. https://doi.org/10.37506/v11/i2/2020/ijphrd/194790.

Albert Anand U, Mariet Caroline P, Arun B, Lakshmi GG. A Study to analyse the efficacy of modified pilates based exercises and therapeutic exercises in individuals with chronic non specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Physiother Res. 2014;2:525–9.

Das D, Venkatesan R. Dynamic sitting exercise versus spinal extension exercise on pain, lumbar mobility and quality of life in adults with mechanical low back pain. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther - An Int J 2020;14. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijpot.v14i1.3279.

Tawrej P, Kaur R, Ghodey S. Immediate effect of muscle energy technique on quadratus lumborum muscle in patients with non-specific low back pain. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther - An Int J 2020:180–4. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijpot.v14i1.3422.

Sawant RS, Shinde SB. Effect of hydrotherapy based exercises for chronic nonspecific low back pain. Ind J Physiother Occup Ther - An Int J. 2019;13:133. https://doi.org/10.5958/0973-5674.2019.00027.3.

Gupta P, Mohanty PP, Pattnaik M. The effectiveness of aerobic exercise program for improving functional performance and quality of life in chronic low back pain. Ind J Physiother Occup Ther - An Int J. 2019;13:155. https://doi.org/10.5958/0973-5674.2019.00064.9.

Mane NP, Varadharajulu G, Shinde S. Effect of motor control training on isolated lumbar stabilizer and core muscle training in chronic low back pain patients. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev. 2019;10:37–42. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2019.01533.X.

Inani SB, Selkar SP. Effect of core stabilization exercises versus conventional exercises on pain and functional status in patients with non-specific low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26:37–43. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2012-0348.

Goel P, Veqar Z, Quddus N. Effects of local vs global stabilizer strengthening in chronic low back pain. Ind J Physiother Occup Ther. 2010;4:68–74.

Naik Prashant P, Heggannavar A, Khatri SM. Comparison of muscle energy technique and positional release therapy in acute low back pain - RCT. Ind J Physiother Occup Ther Int J. 2010;4:32–6.

Zishan M, Samal S, Selkar S, Ramteke S. Efficacy of menthol infused kinesiotaping in forward bending (Flexion) of lumbar spine in mechanical low back pain patients: interventional study. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev. 2020;11:209–13. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i4.4560.

Kulkarni M, Agrawal R, Shaikh F. Effects of core stabilization exercises and core stabilization exercises with kinesiotaping for low back pain and core strength in Bharatanatyam dancers. Ind J Physiother Occup Ther - An Int J. 2018;12:1. https://doi.org/10.5958/0973-5674.2018.00070.9.

Khandhar RY, Sathya P, Paul J. Comparative effect of trunk balance exercise over conventional back care exercise in patients with chronic mechanical low back pain. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev. 2020;11:775–80. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i6.9880.

Sturmer G, Viero CCM, Silveira MN, Lukrafka JL, Plentz RDM. Profile and scientific output analysis of physical therapy researchers with research productivity fellowship from the Brazilian national council for scientific and technological development. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-35552012005000068.

Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care. 2005;20:187–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005.

Cook C. Immediate effects from manual therapy: much ado about nothing? J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:3–4. https://doi.org/10.1179/106698110X12804993427009.

Vickers AJ. Underpowering in randomized trials reporting a sample size calculation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:717–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00141-0.

De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration : a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors How can cross-country research on health risks strengthen interventions? Lessons from INTERHEART. Lancet. 2004;364:911–2.

CTRI. Clinical Trials Registry - India ( CTRI ) n.d. http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/login.php (accessed February 1, 2022).

Lindsley K, Fusco N, Li T, Scholten R, Hooft L. Clinical trial registration was associated with lower risk of bias compared with non-registered trials among trials included in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;145:164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.01.012.

BMC. Why study registration is important for the future of research - on medicine n.d. https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/on-medicine/2018/07/05/study-registration-important-future-research/ (accessed February 1, 2022).

Mozetic V, Leonel L, Leite Pacheco R, De Oliveira Cruz Latorraca C, Guimarães T, Logullo P, et al. Reporting quality and adherence of randomized controlled trials about statins and/or fibrates for diabetic retinopathy to the CONSORT checklist. Trials. 2019;20:4–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3868-4.

Bachani D, Srivastava R. Burden of NCDs, policies and programme for prevention and control of NCDs in India. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.94703.

Acknowledgements

NA.

Funding

The authors confirm that there is no financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS conceived the research idea; designed the search strategy; ran the search query; extracted, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and prepared the final manuscript. SQ participated in data extraction and analysis. SQ revised the data analysis and revised the final manuscript. Both authors evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A because this study used publicly available, non-patient data gleaned from an internet search, ethical approval was not sought for the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suhail, A., Quais, S. Quality and quantity of clinical trials on low back pain published by Indian physiotherapists. Bull Fac Phys Ther 29, 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43161-024-00185-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43161-024-00185-8