Abstract

Background

Appendicitis is one of the most common paediatric surgical emergencies, however complication with acute portomesenteric venous thrombosis is rare. Our aim is to report a case in our locality and review the clinical features and management of such rare complication.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old boy presented with a 5-day history of fever, periumbilical and right lower quadrant abdominal pain, blood-stained diarrhea and vomiting. Physical examination showed tenderness and guarding over right upper quadrant. Laboratory tests showed elevated inflammatory markers and deranged liver function. Contrast computed tomography scan showed acute appendicitis and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. Our patient was treated with laparoscopic appendicectomy, antibiotics, and anticoagulant, with gradual improvement of thrombus observed.

Conclusion

Our patient and seventeen pediatric case reports regarding the condition since 1990 were included. Atypical presenting symptoms were noted, including RUQ pain (n = 10, 56%), diarrhea (n = 8, 44%), fever (n = 16, 89%), deranged liver function (n = 13, 72%). Patient presenting with RLQ pain were only seen in 22% (n = 4). Diagnosis was made by USG (n = 1, 5%) and computer tomography (n = 15, 83%). Surgical intervention includes early (n = 9, 50%) or interval (n = 4, 22%) laparoscopic or open appendicectomy, laparotomy etc. The most common causative organisms were Escherichiae coli and Bacteroides fragilis. Anticoagulant use and its duration remained controversial. Anticoagulant was used in 14 patients with a mean treatment duration of 7 months, while 4 cases reporting resolution of thrombus without anticoagulant use. A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose patient with acute appendicitis complicated by portomesenteric thrombosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common acute pediatric surgical condition and is commonly seen in 10–19-years-old teenage patients [1]. Septic thrombophlebitis, which is more commonly seen in adults, is an uncommon but severe complication of intra-abdominal infection such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, and pancreatitis. In view of the potential complication of mesenteric or liver infarction and its high mortality, early identification of portomesenteric venous thrombosis is crucial. The exact pathophysiology of septic thrombophlebitis and thrombosis remained unknown, but it is proposed to be related to sepsis-induced endothelial injury, which was one of the risk factors of thrombosis according to Virchow’s triad [2].

In the case report, we will present a case of acute appendicitis complicated with portomesenteric venous thrombosis and discuss on its diagnosis and management.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old boy with insignificant past health presented with a 5-day history of fever, periumbilical and right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain, blood-stained loose stool, and vomiting. There was no family history of hematological diseases.

At the time of presentation, he had fever 39.2 °C with otherwise stable vital signs. Examination showed diffuse abdominal tenderness, which was most severe over right upper quadrant (RUQ) with guarding but negative Murphy’s sign. Laboratory tests showed elevated white cell count (WCC) of 15.7 × 109/L with absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) of 12.7 × 109/L and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 272.0 mg/L. There was also deranged liver function at presentation, with normal total bilirubin 20 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) up to 552 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 141 U/L, and deranged clotting profile with prolonged prothrombin time (PT) 13.9 s and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 39.5 s. Platelet count was normal 201 × 109/L. X-rays were unremarkable.

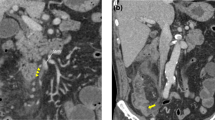

Top differential diagnosis upon clinical assessment included ruptured appendicitis, ruptured hollow viscus, gastroenteritis, and hepatitis. Therefore, contrast computed tomography (CT) scan was arranged in view of the atypical presentation, showing a ruptured dilated 1.2 cm acute necrotic appendicitis and filling defect in superior mesenteric vein before joining the portal vein (Fig. 1a). Patchy hypoenhancement was also detected over right hepatic lobe (Fig. 1b), suspicious of suboptimal blood supply to the liver.

Computed tomography scan on day of admission. a Computed tomography scan on day of admission showing filling defect in superior mesenteric vein (arrow). b Computed tomography scan on day of admission showing patent left and right portal vein and filling defect in superior mesenteric vein. c Computed tomography scan on day of admission showing patent main portal vein. d Computed tomography scan showing patchy hypoenhancement over right hepatic lobe (arrow)

Emergency laparoscopic appendicectomy was performed on day 1 of hospitalization with operative findings of ruptured appendicitis with no evidence of bowel or liver ischemic changes seen laparoscopically. Preoperative intravenous antibiotics with Meropenem 40mg/kg was given. No anticoagulation was started before operation. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were performed, with the blood culture yielding Escherichia coli and peritoneal fluid culture yielding multiple organisms from the genera of Bacteroides, Slackia, Gemella, and Parvimonas.

The early post-operative course was eventful with systemic inflammatory response syndrome with tachycardia, fever, bilateral pleural effusion requiring respiratory support and elevated WCC, requiring admission to pediatric intensive care unit. He was kept nil by mouth to promote bowel rest and prevent bowel ischemia. He was also started on intravenous antibiotics (initially Amikacin 15 mg/kg/dose Q24H, Meropenem 40mg/kg/dose Q8H, Vancomycin 10 mg/kg/dose Q8H and Flagyl 7.5/kg/dose Q8H, later to Cefotaxime 40 mg/kg/dose Q8H and Flagyl 10 mg/kg/dose Q8H according to culture results, respiratory support by high flow oxygen and started on fish-oil based total parenteral nutrition with aggressive fluid replacement regimen. However, there was progressive derangement of liver function with ALP 791 U/L, ALT85U/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 356 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 356 U/L, bilirubin 22 μmol/L and elevation of platelet up to 1112 × 109/L. A follow-up contrast CT scan was arranged on day 7 showing interval progression of portomesenteric thrombosis involving superior mesenteric vein (SMV), main portal vein, proximal right portal vein and left portal vein and its branches. In view of the progression of thrombosis, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at a dosage of 0.8 mg/kg Q12H was started (Fig. 2).

Patient showed gradual improvement clinically with resolution of tachycardia, fever, and weaned off respiratory support. Inflammatory markers and liver function were normalized at post-operative 4 weeks. LMWH dose was further titrated against regular blood anti-Xa monitoring for LMWH was done with a target range of 0.5–1.0units/ml. He was discharged at post-operative 5 weeks with oral levofloxacin, flagyl, and intramuscular enoxaparin. All hematological workup so far showed that patient has no underlying clotting disorder.

Gradual improvement of thrombus was observed on the 4 weeks post-operative CT scan and partial recanalization of hepatic and portal veins. Multidisciplinary approach was adopted with expert opinions from Radiologist and Paediactric Hematologist obtained. Since the infective source was removed, LMWH was stopped at post-operative 6 months as thrombosis likely secondary to the infective episode. Also, long term follow-up for portal hypertension with ultrasound was planned.

Discussion

Septic thrombophlebitis is a rare but potentially fatal complication of intra-abdominal infection. Therefore, early detection and proper management is paramount. A literature review of all reported case in English language using PubMed, MEDLINE, and ScienceDirect since 1990 was reviewed. The clinical presentation, laboratory results, diagnostic modalities, extent of thrombosis, culture results and final treatment were summarized and presented. Our patient and the 17 pediatric case reports regarding the condition since 1990 were included (Table 1).

Presentation of acute appendicitis with septic thrombosis can vary from days to weeks of abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting or fever [3, 4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 14,15,16,17] to persistent pain or vomiting and diarrhea post-appendectomy [5, 13, 16]. The most common presenting symptom were fever (n = 16/18, 89%), deranged liver function (n = 13, 72%), RUQ pain (n = 10, 56%) and diarrhea (n = 8, 44%). Patient presenting with RLQ pain were only seen in (n = 4, 22%). Only one patient out of the whole case series was found to have an underlying Protein S/C, anti-thrombin III deficiency. The most common causative organisms were Escherichiae coli and Bacteroides fragilis.

In regard of the diagnostic imaging modality, even though ultrasound remains the first-line imaging modality for suspected acute appendicitis in pediatrics to minimize childhood radiation [18], computed tomography (CT) scan was helpful in case of acute appendicitis with septic thrombosis. Diagnosis was made by computer tomography (n = 15, 83%), ultrasound (USG) (n = 1, 5%), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (n = 1, 5%) and laparotomy (n = 1, 5%). CT scan also allowed detection of other complications including liver abscess and bowel ischemia. Five cases developed liver abscess following the portal branches of septic thrombophlebitis [3, 9,10,11, 14] However, there was no reported case developing bowel ischemia following portomesenteric thrombosis-complicating appendicitis in pediatrics. Regarding the follow-up imaging for thrombosis, there was no consensus over the modality of imaging used. Doppler ultrasound, CT scan, or even magnetic resonance imaging were used in the case reports. Comparing to doppler ultrasound, CT scan might bear the advantage of detailed and non-operator-dependent scanning, but also bear risks of radiation if repeated follow-up scans are needed. In our case, patient was initially followed up by CT scan for progress of progression and later by ultrasound for any portal hypertension as a long-term follow-up.

For the management of acute appendicitis complicated with portomesenteric thrombophlebitis, adequate sepsis control including broad-spectrum antibiotics and appendectomy were well adopted in the reported cases [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Surgical intervention includes early operative intervention (n = 13, 50%) including laparoscopic or open appendicectomy (n = 12, 66.7%), ileocolic resection (n = 1, 5.6%), and right hemicolectomy (n = 1, 5.6%). Concomitant thrombectomy was seen in 1 patient. Four patients (n = 4, 22.2%) had interval appendicectomy with a median time of 3.5 months after presentation (range 0.5 to 4 months).

Anticoagulant was used in 14 patients with a mean treatment duration of 7 months (ranged from 3 months to 1.5 years) [2, 5, 6, 8,9,10,11,12,13, 15,16,17]. However, anticoagulant use and its duration remained controversial with 4 cases reporting resolution of thrombus without anticoagulant use. The American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism suggested that for provoked venous thromboembolism events, duration of anticoagulation should be less than or equal to 3 months in pediatrics if provoking factor resolves [19]. Antithrombotic Therapy in Neonates and Children Guideline suggested thromboembolism to be managed with pediatric hematologists with a monitoring of anti-Xa blood level if low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is prescribed [20]. In our case, we had consulted pediatric hematologists for their expert opinions before starting on LMWH with regular anti-Xa monitoring. Sepsis was well controlled with appendectomy and board-spectrum antibiotics with follow-up CT scans showed interval reduction of portomesenteric thrombus at post-operative 1 month and partial recanalization at post-operative 6 months. Therefore, anticoagulant was offed at post-operative 6 months.

Conclusion

Portomesenteric thrombosis as a rare but severe complication of acute appendicitis. A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose patient with acute appendicitis complicated by portomesenteric thrombosis. It should be considered in patient with atypical presentation especially with fever and RUQ pain. Management might include appendectomy, antibiotics and anticoagulants. In view of the controversial use of anticoagulants, multidisciplinary management with pediatric hematologist consultation for individualized management might provide additional benefit.

Availability of data and materials

Available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- APTT:

-

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- ANC:

-

Absolute neutrophil count

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GGT:

-

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- LMWH:

-

Low molecular weight heparin

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- RLQ:

-

Right lower quadrant

- RUQ:

-

Right upper quadrant

- SMV:

-

Superior mesenteric vein

- USG:

-

Ultrasound

- WCC:

-

White cell count

References

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734.

Lole Harris BH, Walsh JL, Nazir SA. Super-mesenteric-vein-expia-thrombosis, the clinical sequelae can be quite atrocious. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;28(4):445–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0040.

Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely WF, McNeely BU. A 15-year-old boy with fever of unknown origin, severe anemia, and portal-vein thrombosis. (Case 22-1991) (Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital). N Engl J Med. 1991;324(22):1575.

van Spronsen FJ, de Langen ZJ, van Elburg RM, Kimpen JL. Appendicitis in an eleven-year-old boy complicated by thrombosis of the portal and superior mesenteric veins. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(10):910–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199610000-00017.

Eire PF, Vallejo D, Sastre JL, Rodriguez MA, Garrido M. Mesenteric venous thrombosis after appendicectomy in a child: clinical case and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(12):1820–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90295-0.

Kader HA, Baldassano RN, Harty MP, Nicotra JJ, Von Allmen D, Finn L, et al. Ruptured Retrocecal Appendicitis in an Adolescent Presenting as Portal-Mesenteric Thrombosis and Pylephlebitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27(5):584–8.

Schmutz GR, Benko A, Billiard JS, Fournier L, Peron JM, Fisch-Ponsot C. Computed tomography of superior mesenteric vein thrombosis following appendectomy. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23(6):563–7.

Vanamo K, Kiekara O. Pylephlebitis after appendicitis in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(10):1574–6.

Chang TN, Tang L, Keller K, Harrison MR, Farmer DL, Albanese CT. Pylephlebitis, portal-mesenteric thrombosis, and multiple liver abscesses owing to perforated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(9):19–21.

Pitcher R, McKenzie C. Simultaneous ultrasound identification of acute appendicitis, septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein and pyogenic liver abscess. S Afr Med J. 2003;93(6):426–8.

Nishimori H, Ezoe E, Ura H, Imaizumi H, Meguro M, Furuhata T, et al. Septic Thrombophlebitis of the Portal and Superior Mesenteric Veins as a Complication of Appendicitis: Report of a Case. Surg Today. 2004;34(2):173–6.

Stitzenberg KB, Piehl MD, Monahan PE, Phillips JD. Interval Laparoscopic Appendectomy for Appendicitis Complicated by Pylephlebitis. JSLS. 2006;10(1):108–13.

Levin C, Koren A, Miron D, Lumelsky D, Nussinson E, Siplovich L, et al. Pylephlebitis due to perforated appendicitis in a teenager. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(5):633–5.

Patel AJ, Ong PV, Higgins JP, Kerner JA. Liver abscesses, pylephlebitis, and appendicitis in an adolescent male. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(12):2546–8.

Gatibelza ME, Gaudin J, Mcheik J, Levard G. Pyléphlébite chez l'enfant: un diagnostic difficile [Pylephlebitis in the child: a challenging diagnosis]. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17(9):1320–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2010.06.014.

Granero Castro P, Raposo Rodríguez L, Moreno Gijón M, Prieto Fernández A, Granero Trancón J, González González JJ, et al. Pylephlebitis as a complication of acute appendicitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102(3):217.

Yoon SH, Lee M, Jung SY, Ho IG, Kim MK, NA. Mesenteric venous thrombosis as a complication of appendicitis in an adolescent. Medicine. 2019;98(48):e18002. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018002.

Thirumoorthi AS, Fefferman NR, Ginsburg HB, Kuenzler KA, Tomita SS. Managing radiation exposure in children--reexamining the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(12):2268–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.09.018.

Monagle P, Cuello CA, Augustine C, Bonduel M, Brandão LR, Capman T, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3292–316. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024786.

Monagle P, Chan A, Goldenberg NA, Ichord RN, Journeycake JM, Nowak-Göttl U, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e737S–801S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2308.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lai collected the data, reviewed the literatures, and drafted the manuscript. Hung and Leung supervised and advised in preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent had been obtained from parents as patient is a minor.

Competing interests

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, T.Y.N., Hung, J.W. & Leung, M.W. Portomesenteric venous thrombosis as a rare complication of acute appendicitis in pediatric patient: a case presentation and literature review. Ann Pediatr Surg 18, 74 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-022-00211-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-022-00211-1