Abstract

Background

Prenatal penetrating gunshot trauma represents a challenging scenario for healthcare providers. Trauma is the leading non-obstetric cause of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy, and even though rare, firearm injuries have the most fatal outcomes and higher fetus mortality rates. Understanding the mechanism of injury in order to identify the possible injuries and adequate management is essential. In this paper, we discuss the case of a newborn with prenatal gunshot trauma, the treatment used, and the outcome of conservative and minimally invasive management.

Case presentation

We present the case of a male newborn, 37 weeks of gestational age and weighing 3050 g, delivered through an emergency cesarean section with prenatal gunshot trauma. Two skin wounds were found, one in the arm and another in the left thoracic region. The patient presented with respiratory distress, bilateral pneumothorax, and pneumoperitoneum, requiring high-frequency mechanical ventilation and the placement of bilateral thoracic drains. The pneumoperitoneum was attributed to pulmonary barotrauma, with no suspicion of abdominal hollow viscera lesion. A right thoracoscopy was performed after 24 h of conservative management for the removal of the foreign body. Both the mother and the baby had a positive outcome, with no further treatment needed.

Conclusions

For the improvement in the result of trauma events, an adequate intervention and coordinated efforts from multidisciplinary clinical and surgical teams are required. For gunshot wounds, entry, trajectory, the final position of the bullet, and pathological findings in images need to be analyzed before taking the patient to the operative room. Chosen with strict selection criteria, some patients could benefit from conservative management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite being a rare entity, prenatal gunshot trauma represents a challenging scenario, with important morbidity and mortality for both mother and baby. A good outcome requires the coordinated effort of multidisciplinary clinical and surgical teams. In this paper, we discuss the case of a newborn with a thoracic prenatal gunshot trauma, who developed bilateral pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum. After initial stabilization, non-operative management was chosen for the pneumoperitoneum, and a minimally invasive treatment was used for the thoracic bullet removal. The result was a good outcome for both the mother and the baby, showing that the use of a conservative treatment for strict selected patients is feasible.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 38-year-old pregnant woman in her third trimester of gestation, who suffered a gunshot wound in the lower abdomen. She was admitted at a general trauma hospital with normal vital signs. At examination, a 2-cm wound was found in the lower abdomen, midway between the pubis and umbilicus, with no exit wound. An emergency cesarean section was performed, with no injuries found in other abdominal organs, and a live male newborn of 37 weeks of gestational age, weighing 3050 g, delivered. APGAR score was 3/6/8, at 1/5/10 min, respectively; the baby presented with respiratory distress and tachycardia immediately after birth. Two skin wounds were found, one in the inner region of the left arm and the other in the left thoracic region, without an exit wound. Mechanical ventilation was required, a left chest tube was placed in the mid-axillary line through the gunshot wound at the 6th intercostal space, and a right drain in the midclavicular line at the second intercostal space, due to bilateral pneumothorax shown in a plain chest X-ray. The arm skin wound was sutured, and the baby was transferred to the neonatal surgical intensive care unit (NICU) at our institution.

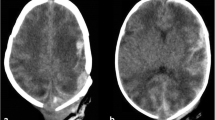

Upon arrival, the patient developed respiratory distress and bradycardia, with low breath sounds in the right hemithorax. A new thoracic tube was placed in the right mid-axillary line, and high-frequency mechanical ventilation was applied. The patient was hemodynamically stabilized, requiring the use of dopamine 10 mcg/kg/min, mean blood pressure was 50 mmHg, heart rate 145 bpm, and oxygen saturation 99%. Abdominal ultrasound and echocardiogram were performed, both showing no pericardium or abdominal fluid, nor solid organ injury, with normal ventricular function. Pneumoperitoneum and mild left pneumothorax were found in the abdominal and chest X-ray, along with a foreign body in the right hemithorax (Fig. 1). Blood gasses were pH 7.4, PCO2 45 mmHg, PO2 219 mmHg, HCT 45, and hemoglobin 15 g/dl. At physical examination, the abdomen was soft with no tenderness; both chest tubes drained scarce hematic fluid.

Pneumoperitoneum was suspected to be related to pulmonary barotrauma and not caused by abdominal hollow viscera injury. Given the good hemodynamic condition of the baby, a non-operative management was chosen. Serial lateral and front thoracic and abdominal X-rays were taken with a 4-h interval, showing improvement of the pneumoperitoneum (Figs. 1 and 2). After 24 h of conservative management, the patient hemodynamically stabilized, a right thoracoscopy was performed for the removal of the foreign body. A 5-mm camera was inserted through the right pleural drain hole, the bullet was found in the pleural cavity, and a video-assisted minimal thoracotomy done for extraction (Fig. 3). A 12-French drain was placed. A conceptual model of the course of action is represented in Fig. 4.

The baby was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for postoperative care and respiratory support. Pleural drains were withdrawn the second day, oral feedings started the third, and the patient was discharged at the fifteenth postoperative day.

Discussion

Trauma is the leading non-obstetric cause of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy [1, 2], with some reports suggesting that between 5 and 20% of pregnant women are exposed to physical trauma [3, 4], most commonly occurring in the third trimester of gestation. Even though blunt trauma is the most frequent mechanism of injury, led by motor vehicle accidents [1], firearm injuries have the most fatal outcomes and higher fetus mortality rates, with a fetal injury rate between 59 and 80%, and a mortality rate between 30 and 70% [1, 5,6,7].

When a pregnant woman is a victim of a penetrating trauma, a higher risk of severe injury exists for the fetus, given maternal visceral organ injuries only occur in 20% of the cases [3]. This is associated with anatomical changes during pregnancy, especially during the last trimester, when uterus position modifications with growth result in a more vulnerable fetal location.

Even though developments have been made in the management of abdominal gunshot wounds [8], they still have high morbidity and mortality rates [3]. When treating a pregnant woman with trauma, the best method of treatment for the fetus is based on the appropriate resuscitation of the mother. Maternal mortality is the most common cause of fetal mortality due to trauma [2, 9] and for this reason, maternal well-being should be established first [3].

Non-operative management is considered the standard of care for blunt injuries and has decreased the rate of unnecessary laparotomy. Despite operative management is still considered the standard of care in penetrating trauma, studies report the tendency to perform an initial non-operative management in some patients with a strict selection criteria [8]. A conservative approach of penetrating injuries in pregnant women is accepted when the entry site is anterior and below the uterine fundus, considering in this case maternal visceral injuries are less likely, if the fetus is previable or dead, maternal evaluation satisfactory and urinalysis negative for blood [3, 4, 10,11,12].

Upon arrival at our institution, the baby presented pneumoperitoneum in the abdominal X-rays. This could be explained by the injury of abdominal hollow viscera, but also it could be secondary to pulmonary barotrauma. Given the good hemodynamic condition of the baby, the soft abdomen, and the study of the bullet trajectory, a non-operative management was chosen. We believe that the patient presented in this case report was clearly benefited from the choice of an expectant approach regarding pneumoperitoneum at our institution, after initial emergency management at the general hospital. Understanding the mechanism of injury in order to identify the possible injuries and adequate management is essential. Molina et al. [7] report a case of a newborn with prenatal gunshot trauma that was explored by means of an unnecessary thoracotomy guided by the location of the entry wound in the thorax, with no thoracic injuries found. We had a similar patient at our institution in 1996, who had a prenatal gunshot wound with a thoracic entry. Initially, a thoracotomy was performed, with no bullet found in the thoracic cavity. A laparotomy was needed to remove the bullet, given its final position was in the abdomen. Entry wound, trajectory, the final position of the bullet, and pathological findings in images need to be analyzed before taking the patient to the operative room.

The literature regarding the management of the new-born who survived a prenatal gunshot is scarce, and there are only a few other cases similar to ours reported. We believe our experience with this case can be useful to other medical teams faced with the same challenging situation.

A consensus plan of action is necessary with all the team members involved in order to increase the chances of survival.

Conclusion

Prenatal penetrating gunshot trauma represents a challenging scenario for healthcare providers. A positive outcome and a fully recovered mother and baby require a multidisciplinary team of pediatric surgeons, neonatologists, emergency physicians, and nurses.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCT:

-

Hematocrit

References

Petrone P, Jiménez-Morillas P, Axelrad A, Marini CP. Traumatic injuries to the pregnant patient: a critical literature review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45(3):383–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0839-x.

Gun F, Erginel B, Günendi T, Celik A. Gunshot wound of the fetus. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27(12):1367–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-011-2915-3.

Karacan T, Ilhan C, Karacaoglu MU. Abdominal gunshot wound to pregnant woman at 22 weeks of gestation: a case report. Balıkesır Health Sci J. 2013;2(2):114–7. https://doi.org/10.5505/bsbd.2013.59144.

Osnaya-Moreno H, Zaragoza Salas TA, Escoto Gomez JA, Mondragon Chimal MA, Torres Castaneda MDL, Jimenez Flores M. Gunshot wound to the pregnant uterus: case report. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2013;35(9):427–31. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-72032013000900008.

Mulder MB, Quiroz HJ, Yang WJ, et al. The unborn fetus: the unrecognized victim of trauma during pregnancy. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(5):938–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.01.047.

Carugno JA, Rodriguez A, Brito J, Cabrera C. Gunshot wound to the gravid uterus with non-lethal fetal injury. J Emerg Med. 2008;35(1):43–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.06.042.

Molina GA, Aguayo WG, Cevallos JM, et al. Prenatal gunshot wound, a rare cause of maternal and fetus trauma, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;59:201–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.05.034.

Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Toutouzas KG, et al. Selective nonoperative management in 1,856 patients with abdominal gunshot wounds: should routine laparotomy still be the standard of care? Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200109000-00013.

Yalinkaya A, Olmez G, Yayla M. Abdominal gunshot wounds during pregnancy: report of two cases. Case Rep Clin Pract Rev. 2005;6:61–4.

Franger AL, Buchsbaum HJ, Peaceman AM. Abdominal gunshot wounds in pregnancy-case reports. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 Pt 1):1124–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(89)90173-7.

Weintraub AY, Leron E, Mazor M. The pathophysiology of trauma in pregnancy: a review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:601–5.

Gungor ES, Sen S, Uzunlar O. Gunshot wound in pregnancy. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1069–70.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No competing financial interests exist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. CG made substantial contributions in the conception and design and drafted the work. AR made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and interpretation of data. BM contributed to the bibliographic search and revised the study. SA contributed to the design and revision of the work. MB made significant contributions in revising the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the research ethics board at our institution.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruhrnschopf, C.G., Reusmann, A., Boglione, M. et al. Neonatal minimal invasive management of a prenatal gunshot trauma: case report. Ann Pediatr Surg 17, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-021-00075-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-021-00075-x