Abstract

Background

The rapid expansion of modern smart applications, demanding faster data transfer and extensive bandwidth, has prompted the development of new-generation networks like 5G and 6G. These networks encompass additional frequency bands such as sub-6 GHz, millimeter waves, and terahertz bands to meet the growing bandwidth requirements. However, despite the substantial bandwidth available in these bands, several challenges must be addressed to overcome unfavorable propagation characteristics. Moreover, numerous applications necessitate wireless devices with antennas that exhibit high flexibility and exceptional radiation responses, particularly when subjected to bending effects. This requirement highlights the importance of polymers-based antennas that can adapt to changing conditions while maintaining optimal performance. The present comprehensive study delves into the performance evaluation of rectangular and circular microstrip antennas utilizing PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) polymer substrate with varying thicknesses.

Results

Notably, CNTs (Carbon Nanotubes) are employed as an alternative to traditional copper for the conductive part and ground plane. Both PMMA-based antennas, integrated with CNTs, exhibit a compact footprint of 27.8 × 47.8 × 1.5 mm3 for the circular antenna and 22.8 × 39.5 × 1.5 mm3 for the rectangular antenna. Impressively, the realized gain of both antennas surpasses 5 dBi, demonstrating robust performance in both flat and bending scenarios across different substrate thicknesses.

Conclusions

The rectangular antenna achieves a bandwidth of approximately 200 MHz, while the circular microstrip antenna showcase annotable bandwidth of 500 MHz. These exceptional outcomes position the two microstrip antennas as highly suitable for a diverse range of emerging applications within the sub-6 GHz band (the frequency range below 6 GHz in the radio spectrum). Thus, the combination of PMMA substrate, CNTs and the compact form factor of the antennas presents a compelling solution for meeting the demands of modern applications requiring efficient wireless communication with enhanced performance and bandwidth.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

The advent of 5G and the emerging era of 6G networks hold the promise of connecting billions of devices, each with its own unique set of constraints and behaviors [1,2,3,4]. This upsurge in demand can be attributed to the convergence of various aspects of our daily lives toward smart systems and wireless connected devices [5,6,7,8,9]. From our homes to our workplaces, from transportation to healthcare, we find ourselves relying on an interconnected web of devices and systems that enhance our efficiency, convenience, and overall quality of life [10,11,12,13,14]. The proliferation of smart home technologies [15, 16], wearable devices [17, 18], and the Internet of Things (IoT) has accelerated this transformation, creating a landscape where wireless connectivity has become an indispensable part of our existence [19,20,21,22,23]. Undoubtedly, the emergence of wireless communications is closely linked to recent advancements in antenna design and manufacturing, which have been revolutionized by innovative design procedures involving artificial intelligence and deep learning methods [24,25,26,27,28,29]. These antennas are designed to operate across a wide range of frequency bands, while ensuring compatibility with the diverse environmental conditions found in various installations [30, 31]. Not to mention the cost factor, which also plays a crucial role [32].In addition to the RF bands commonly used for various traditional applications, the need for increased bandwidth has compelled 5G and 6G consortiums to explore additional bands, including millimeter wave, sub-6G, and terahertz bands. This is driven by the significant growth in bandwidth requirements [33,34,35]. The design of antennas operating in these frequency bands, while considering installation conditions, is directly linked to the choice of materials used for the antenna substrate and its patch, which represents a challenging research topic in this field [36,37,38]. Polymers, such as PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate), are considered as potential candidates for the design of future antennas, since they offer several advantages, including lightweight [38], flexibility [39, 40], and low-cost manufacturing capabilities [41]. PMMA polymer is widely used for plastic optical fibers (POFs) that are suitable for various applications like data communication and sensing in environments where traditional glass fibers may not be practical [42,43,44]. Additionally, PMMA-based fiber Bragg sensors are gaining prominence for their ability to measure strain, temperature, and other physical parameters with high sensitivity and reliability [45,46,47,48]. However, it is important to note that research and development in this field are still ongoing to optimize the properties of polymers and validate their use in specific antenna applications, especially within the aforesaid frequency bands [49,50,51,52]. Therefore, the current study focuses on investigating the impact of using PMMA as a substrate for the design of rectangular and circular patch antennas intended for applications in the sub-6 GHz band. Several polymers have been utilized in literature to address the challenges posed by next-generation networks in terms of gain, bandwidth efficiency, and ease of environmental installation. In [53], authors have performed a review on the involvement of the metamaterials for designing reconfigurable antennas for 5G and 6G networks. Authors in [54] have implemented RT/duroid 5880 laminates as a substrate for designing quad band antennas operating at mmwaves bands. The improvement of the electrical and radiation properties is realized by using a binary-coded genetic algorithm. In [55], authors have proposed a circularly polarized antenna for IoT energy constrained devices, measuring 15 × 35 mm2, serves as a versatile portable RF energy harvesting device, resonating from 2 to 10 GHz with band notches from 2.5 to 3.5 GHz, while a voltage double rectifier (VDR) with a 9.2 × 20 mm2 size converts RF to DC with a wideband of operation from 2 to 10 GHz, achieving a maximum DC output voltage of 0.94 V, 60% power conversion efficiency at -5 dBm input signal. Authors in [56] have studied the bending effect of polymer-based antennas intended for IoT devices, where numerous flexible materials were studied such as Polyimides (Pi), Liquid Crystal polymer (LCP), Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Rogers RT/Duroid. Authors in [57] have demonstrated the use of chitosan polymer as substrate of ecofriendly antennas instead of plastic substrates. As chitosan is classified as sustainable material, the proposed antenna with 1 dBi realized gain, is proposed for healthcare IoT devices. In [58], authors have designed a natural rubber substrate based antenna with 80 mm telemetry range. The proposed antenna is intended for on-body devices. In addition, CNTs have been widely involved in various smart applications because of their excellent elctrolmechanical smart applications, such as THZ wave absobers, strain and piezoelectric sensors, smart wearables, and so on [59,60,61,62].

The present in-depth study investigates the performance of rectangular and circular microstrip antennas utilizing PMMA substrate with varying thicknesses. In place of traditional copper, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) are employed for the conductive part and ground plane. Both PMMA-based antennas combined with CNTs demonstrate a compact size of 27.8 × 47.8 × 1.5 mm3 for the circular antenna and 22.8 × 39.5 × 1.5 mm3for the rectangular antenna.Remarkably, the realized gain exceeds 5 dBi for both antennas, exhibiting strong performance in both flat and bending scenarios across different substrate thicknesses.

2 Materials and methods

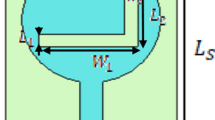

2.1 Circular antenna design procedure

The outlined procedure for designing the proposed antenna is comprehensive and detailed in this section. Initially, the design focuses on creating a circular patch antenna, utilizing carbon nanotubes (CNT) as the conductive material for both the circular-shaped patch and the ground plane. These components are printed on a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) dielectric substrate with a permittivity of of \(\varepsilon_{{\text{r}}} = 2.546\). The process commences with determining the antenna dimensions using Eqs. (1–4) [63] to achieve resonance at a frequency of \(f_{{\text{r}}} = 5.8\;{\text{ GHz}}\). The CNT radiating element and ground plane possess an electrical conductivity of \(3e^{5} \;{\text{S/m}}\) and a thermal conductivity of \(1000 \;{\text{W/K/m}}\). Additionally, they have a density of approximately \(0.81\;{\text{g/cm}}^{3}\), and they have a thickness of \(0.035\;{\text{ mm}}\). A visual representation of the basic circular antenna is provided in Fig. 1.

where c is the speed of ligth, \(f_{{\text{r}}}\) is the resonant frequency and \(\varepsilon_{{\text{r}}}\) is the relative permittivity of the substrate and \(d\) is its thickness where \(d \ll \lambda\). The antenna is fed by a microstrip line of width (Wf) of 3.1 mm and a length of \(\left( {L_{{\text{f}}} } \right)\).

2.1.1 Return loss and L-shape impedance matching

The parameter S11, often referred to as the reflection coefficient or return loss, represents the amount of power reflected from the antenna. It is calculated using the Eq. (5):

\(\Gamma\): refers to the reflection coefficient, \(V_{{{\text{ref}}}} :\) the amount of the reflected voltage, \(V_{{{\text{inc}}}}\): the amount of the incident voltage.

The overall anetnna dimensions according to the above equations are 42.8 × 62.8 mm2 (0.82 \(\lambda_{r}\) × 1.21 \(\lambda_{r}\)).

The normalized S11 value, often expressed as a percentage or in dB, provides a clearer indication of the level of impedance matching. A lower normalized S11 value indicates better impedance matching and reduced reflection, ultimately leading to more efficient power transfer from the transmitter to the antenna. When S11 = 0 dB, it signifies that all the power is reflected from the antenna, indicating poor impedance matching. Conversely, lower magnitudes of S11 indicate better impedance matching and reduced reflection [63].

The antenna return loss is depicted in Fig. 2, revealing challenges in achieving satisfactory impedance matching at the desired frequency due to the presence of multiple other frequencies. To address this issue, the design implements the use of slots which are inserted on the radiating element in a second step. This intervention aims to enhance antenna impedance matching and simultaneously minimize antenna size.

The optimal locations for slot insertion are designated by analyzing the antenna’s current density at its resonant frequency, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Elevated current density is observed around both the feed line and the edges of the circular structure. Consequently, slots are strategically inserted at these regions of high current density to induce a corresponding change in the antenna's response, optimizing its performance accordingly.

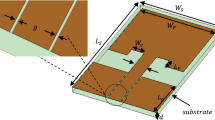

The design procedure for the proposed antenna is illustrated in Fig. 4. Initially, we introduce a horizontal slot, followed by the addition of a second vertical slot to optimize the antenna’s performance. Through several parametric studies to determine the dimensions of the slots, we achieve the desired results depicted in Fig. 5, showcasing an impressive return loss of − 19.91 dB at the resonant frequency with a bandwidth of 264 MHz. Consequently, the final design of the proposed antenna with the inverted L-slot configuration attains dimensions of 27.8 × 47.8− mm2, corresponding to 0.54λr *0.92λr.

The final antenna parameters values are summarized in Table 1.

2.1.2 Realized gain and far field pattern for the circular antenna

The simulated antenna’s realized gain and far-field radiation pattern (for both E and H planes) at 5.8 GHz are presented in Fig. 6. As depicted, the radiation exhibits a predominantly omnidirectional pattern, which is suitable for receiving information signals from all directions. The antenna's gain at 5.8 GHz is approximately 4.76 dBi.

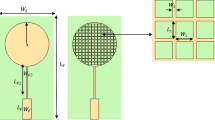

2.2 Rectangular antenna design

The proposed microstrip antenna is based on a rectangular shape, as depicted in Fig. 7. The antenna is designed on a PMMA substrate with a dielectric permittivity of \(\varepsilon_{{\text{r}}} = 2.546\), a thickness of \(d = 0.8\;{\text{ mm}}\), and dimensions of \(12\; \times \;18\; {\text{mm}}^{2}\). Both the CNT ground plane and the radiating element have a thickness of \(t = 0.035 \;{\text{mm}}\). The antenna dimensions are evaluated using Eqs. (6–10) [64].

where c is the speed of ligth, f is the resonant frequency (5.8 GHz) and \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{eff}}}}\) is the effective relative permittivity.

2.2.1 Return loss and quarter-wavelength transformer for impedance matching

The rectangular-shaped patch is fed by a microstrip line with a characteristic impedance of 50Ω. In order to adapt the antenna to its feed, the width of this line is evaluated based on Eq. (10)

where \(w_{{\text{f }}}\) the feed line width and d represents the substrate thickness.

The antenna response in terms of return loss is presented in Fig. 8, revealing suboptimal impedance matching below − 10 dB at the desired frequency. To rectify this issue and enhance the antenna’s impedance matching, a quarter-wavelength transformer has been integrated, as depicted in Fig. 9. The final antenna geometry, showcased in Fig. 9, demonstrates improved impedance matching. Furthermore, Fig. 10 illustrates the antenna return loss, highlighting its enhanced matching performance. Detailed parameter dimensions for the final antenna design are provided in Table 2, measuring 22.8 × 39.5 mm², corresponding to 0.44 λrx by 0.76 λr.

2.2.2 Realized gain and far field pattern for the rectangular antenna

The simulated antenna realized gain and far-field radiation pattern (for both E and H planes) at 5.8 GHz are presented in Fig. 11. As shown, the antenna exhibits a quasi-omnidirectional far field with a realized gain of 3.1 dBi at 5.8 GHz.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Impact of the thickness ‘d’ for the return loss and the realized gain

Figures 12 and 13 depict the return losses of the circular and rectangular antennas, respectively, across various substrate thicknesses. This investigation endeavors to elucidate the impact of substrate thickness on antenna performance, encompassing factors such as impedance matching, gain, and radiation efficiency.

For the circular antenna, we observe that lower thicknesses result in a wider bandwidth compared to higher values. Conversely, we note an improvement in gain (Fig. 14) and efficiency values with increasing thickness. To strike a balance between impedance matching and gain, optimizing the dimensions of the slots is necessary to achieve a reasonable return loss. In our study of the circular antenna, we observe that slot 2 has a significant effect on enhancing antenna return loss around the \(5.8 \;{\text{GHz}}\) band (see Fig. 5), indicating the importance of studying the impact of its dimensions. It is evident from Fig. 15 that the antenna impedance matching is visibly enhanced, particularly for \(L_{2} = 40\;{\text{ mm}}\) and \(W_{2} = 3 \;{\text{mm}}\).For the rectangular antenna, we observe a slight shift in the resonance frequency as the substrate becomes thicker. As expected, the antenna gain improves with increasing substrate thickness, as illustrated in Fig. 16. Table 3 summarizes all the studied thicknesses.

3.2 Bending effect

The bending study primarily aims to investigate the response of flexible antennas in various scenarios and assess their ability to maintain good performance when implemented in practical applications. To evaluate the behavior of our antennas in such situations, we consider a vacuum cylinder to bend the antennas for different radii, thereby altering the degree of curvature. The dimensions of the antennas remain fixed as they are in a flat situation. Figures 17 and 18 depict the return losses of the circular and rectangular antennas, respectively.

The circular antenna is initially bent in the E plane and then in the H plane. We observe that the antenna’s impedance matching exhibits a slight shift to lower frequencies in the E plane. This shift is primarily caused by changes in the antenna’s effective length during the bending process, as well as alterations in the current distribution in this plane [64, 65]. However, the antenna maintains its good performance even with very small radii (R = 7 mm: severely bent) due to its large bandwidth, despite the frequency shift. Along the H plane, the antenna shows no resonant frequency offset, as the current path remains unaffected compared to the E plane. This is evident from Fig. 17b, where it maintains good matching until R = 10 mm.

In the E-plane bending for the rectangular antenna, the bending does not significantly affect the antenna response, while in the H-plane bending, it strongly impacts the antenna performance. Even with large radii (R = 19 mm), as specified in Fig. 18b, the antenna’s performance is notably affected. It is evident that the magnitude of the return loss increases when the antenna is bent, although the rectangular antenna experiences a significant increment even when slightly bent, compared to the circular antenna, which maintained the return loss under − 10 dB.

Tables 4 and 5 present the gain and efficiencies of the bent antennas, respectively, for a similar bending radius (R = 20 mm). We observe that both antennas’ gains are more affected in the E plane bending compared to the H plane bending. This can be explained by the fact that the current density is accumulated at the center of the antenna in the H plane, which increases the magnetic field, whereas in the E plane, the current is gathered at the antenna's side, leading to a decrease in its gain [66].

Furthermore, it is evident from Tables 4 and 5 that the rectangular antenna exhibits significant changes in its gain (in both E and H planes) compared to the flat situation. This behavior can be attributed to the edgy shape of the rectangular antenna.

This analysis shows the effectiveness of circular antennas which is less edgy and more stable comparing to rectangular antennas.

3.3 Comparative study between circular and rectangular design (PMMA-CNT)

We observe differences in the electrical and radiation performances between the circular and rectangular antenna structures, despite utilizing the same substrate and conductive materials characteristics. Notably, the circular antenna maintains a stable resonance frequency of approximately 5.8 GHz across varying substrate thicknesses, while also offering a wider bandwidth (5.51–6 GHz) compared to the rectangular antenna (5.47–5.68 GHz). Additionally, the circular antenna demonstrates superior gain performance, with nearly a 1 dBi difference compared to the rectangular antenna.

In the existing literature, there is a lack of examples combining PMMA substrate with CNT conductive materials. Therefore, we conducted a comparative analysis with antennas from recent related works, which were designed using different substrate and conductive materials. This comparison, detailed in Table 6, emphasizes factors such as compactness (antenna size), performance, and dielectric properties. Our findings indicate that while some reported antennas achieve good gains, they often do so at the expense of larger dimensions or lower efficiency. In contrast, our designs strike a suitable compromise between size, gain, and efficiency, highlighting their practical viability in real-world applications.

4 Conclusions

The present in-depth study investigates the performance of rectangular and circular microstrip antennas utilizing PMMA substrate polymer with varying thicknesses. In place of traditional copper, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) are employed for the conductive part and ground plane. Both PMMA-based antennas combined with CNTs demonstrate a compact size of 27.8 × 47.8 × 1.5 mm3 for the circular antenna and 22.8 × 39.5 × 1.5 mm3 for the rectangular antenna. Remarkably, the realized gain exceeds 5 dBi for both antennas, exhibiting strong performance in both flat and bending scenarios across different substrate thicknesses. The rectangular antenna achieves a bandwidth of approximately 200 MHz, while the circular microstrip antenna reaches an impressive 500 MHz bandwidth. These exceptional outcomes make the two microstrip antennas highly suitable for a wide range of emerging applications within the sub-6 GHz band, including but not limited to wireless communication systems and Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in the present study are available on request.

References

Yeh C, Do Jo G, Ko YJ, Chung HK (2023) Perspectives on 6G wireless communications. ICT Expr 9(1):82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icte.2021.12.017

Salahdine F, Han T, Zhang N (2023) Security in 5G and beyond recent advances and future challenges. Secur Pri 6(1):e271. https://doi.org/10.1002/spy2.271

Vaezi M, Azari A, Khosravirad SR, Shirvanimoghaddam M, Azari MM, Chasaki D, Popovski P (2022) Cellular, wide-area, and non-terrestrial IoT: a survey on 5G advances and the road toward 6G. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor 24(2):1117–1174. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2022.3151028

Jornet JM, Knightly EW, Mittleman DM (2023) Wireless communications sensing and security above 100 GHz. Nat Commun 14(1):841. https://doi.org/10.1049/PBTE099E

Mehmood R, Sheikh A, Catlett C, Chlamtac I (2022) Smart societies, infrastructure, systems, technologies, and applications. Mob Netw Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11036-022-01990-y

Zhang X, Ming X (2023) A smart system of customer-product Interaction Life Cycle (CILC) in industrial Internet era for mass personalization from industrial practice survey: identification, definition, acquisition and parsing. J Intell Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-022-02070-4

Barata J, Kayser I (2023) Industry 5.0–past, present, and near future. Proc Comput Sci 219:778–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.351

Gera R, Chadha P, Khera GS, Yadav R (2023) A comprehensive and narrative review of industry 5.0 technologies: 2018–2022. Renew Energy Optim Plan Control: Proc ICRTE 2022:237–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8963-6_23

Ashraf S, Ahmed T, Aslam Z, Muhammad D, Yahya A, Shuaeeb M (2020) Depuration based efficient coverage mechanism for wireless sensor network. J Electr Comput Eng Innov (JECEI) 8(2):145–160. https://doi.org/10.22061/jecei.2020.6874.344

Horng GJ (2023) Advances of future IoE wireless network technology. Electronics 12(10):2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12102164

Yudidharma A, Nathaniel N, Gimli TN, Achmad S, Kurniawan A (2023) A systematic literature review: messaging protocols and electronic platforms used in the internet of things for the purpose of building smart homes. Proc Comput Sci 216:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.127

Chatrati SP, Hossain G, Goyal A, Bhan A, Bhattacharya S, Gaurav D, Tiwari SM (2022) Smart home health monitoring system for predicting type 2 diabetes and hypertension. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci 34(3):862–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.01.010

Plageras AP, Psannis KE (2023) IOT-based health and emotion care system. ICT Expr 9(1):112–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icte.2022.03.008

Prasad C, Madkhali N, Lee BM, Kang CS, Choi HY (2023) Recent developments in GO/Cellulose based composites: properties, synthesis, and its applications. Polymer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2023.125786

Kshirsagar PR, Reddy DH, Dhingra M, Dhabliya D, Gupta A (2022) A Review on comparative study of 4G, 5G and 6G networks. In: 2022 5th international conference on contemporary computing and informatics (IC3I), IEEE, pp 1830–1833. https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3I56241.2022.10073385

AlQahtani AAS, Alamleh H (2023) Optimizing smart home performance and user convenience with RSSI-based proximity detection. In: 2023 IEEE 13th annual computing and communication workshop and conference (CCWC), IEEE, pp 0319–0325, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCWC57344.2023.10099153

Singh PK, Singh SK, Mallik S, Choudhary DK, Tiwary AK (2022) A survey on antennas for IIoT application. In: Industrial internet of things. CRC Press, pp 273–284

Heiding F, Süren E, Olegård J, Lagerström R (2023) Penetration testing of connected households. Comput Secur 126:103067

Rani T, Das SC, Hossen MS, Paul LC, Roy TK (2022) Development of a broadband antenna for 5G Sub-6 GHz cellular and IIoT smart automation applications. In: 2022 12th international conference on electrical and computer engineering (ICECE). IEEE, pp 465–468. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECE57408.2022.10088497

Muqdad ZS, Alibakhshikenari M, Elwi TA, Hassain ZAA, Virdee BS, Sharma R, Limiti E (2023) Photonic controlled metasurface for intelligent antenna beam steering applications including 6G mobile communication systems. AEU-Int J Electron Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2023.154652

Portilla L, Loganathan K, Faber H, Eid A, Hester JG, Tentzeris MM, Pecunia V (2023) Wirelessly powered large-area electronics for the Internet of Things. Nat Electron 6(1):10–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-022-00898-5

Ashraf S, Alfandi O, Ahmad A, Khattak AM, Hayat B, Kim KH, Ullah A (2020) Bodacious-instance coverage mechanism for wireless sensor network. Wirel Commun Mob Comput 2020:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8833767

Ahmad A, AyazUllah CF, Khan M, Ashraf S, Adnan M, Nazir S, Khan H (2020) toward an improved energy efficient and end-to-end secure protocol for IoT healthcare applications. Secur Commun Netw 2020:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8867792

Urimubenshi F, Konditi DB, de Dieu Iyakaremye J, Mpele PM, Munyaneza A (2022) A novel approach for low mutual coupling and ultra-compact Two Port MIMO antenna development for UWB wireless application. Heliyon 8(3):e09057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09057

Jain H, Chakravarti P, Kumar A (2023) A comprehensive review on UWB multi-notch antennas. In: Intelligent systems and smart infrastructure: proceedings of ICISSI 2022, 250

Abo-Hammour ZE, Alsmadi O, Momani S, Abu Arqub O (2013) A genetic algorithm approach for prediction of linear dynamical systems. Math Probl Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/831657

Abo-Hammour Z, Abu Arqub O, Momani S, Shawagfeh N (2014) Optimization solution of Troesch’s and Bratu’s problems of ordinary type using novel continuous genetic algorithm. Discret Dyn Nat Soc. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/401696

Abu Arqub O, Abo-Hammour Z, Momani S, Shawagfeh N (2012) Solving singular two-point boundary value problems using continuous genetic algorithm. In: Abstract and applied analysis, Hindawi, Vol. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/205391

Arqub OA, Abo-Hammour Z (2014) Numerical solution of systems of second-order boundary value problems using continuous genetic algorithm. Inf Sci 279:396–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2014.03.128

Sarkar D, Khan T, Talukdar FA, Antar YM (2023) Computational intelligence paradigms for UWB antennas: a comprehensive review of analysis, synthesis and optimization. Artif Intell Rev 56(1):655–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10181-w

Jeong H, Park E, Phon R, Lim S (2022) Mechatronic reconfigurable intelligent-surface-driven indoor fifth-generation wireless communication. Adv Intell Syst 4(12):2200185. https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202200185

Chishti AR, Aziz A, Qureshi MA, Abbasi MN, Algarni AM, Zerguine A, Hussain R (2022) Optically transparent antennas: a review of the state-of-the-art, innovative solutions and future trends. Appl Sci 13(1):210

Ramezanpour K, Jagannath J, Jagannath A (2023) Security and privacy vulnerabilities of 5G/6G and WiFi 6: survey and research directions from a coexistence perspective. Comput Netw 221:109515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109515

Lin X (2022) An overview of 5G advanced evolution in 3GPP release 18. IEEE Commun Stand Mag 6(3):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOMSTD.0001.2200001

Miao H, Zhang J, Tang P, Tian L, Zhao X, Guo B, Liu G (2023) Sub-6 GHz to mm wave for 5G-advanced and beyond: channel measurements, characteristics and impact on system performance. IEEE J Select Areas Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2023.3274175

Miao H Sub-6 GHz to mm wave for 5G-advanced and beyond: channel measurements, characteristics and impact on system performance. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2023.3274175

Hadi MU, Murtaza G (2022) Fibre wireless distributed antenna systems for 5G and 6G services. Electronics 12(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12010064

Wang Y, Zhang X, Su R, Chen M, Shen C, Xu H, He R (2023) 3D printed antennas for 5G communication: current progress and future challenges. Chin J Mech Eng: Addit Manuf Front. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjmeam.2023.100065

Whittaker T, Zhang S, Powell A, Stevens CJ, Vardaxoglou JYC, Whittow W (2022) 3D printing materials and techniques for antennas and metamaterials: a survey of the latest advances. IEEE Anten Propag Mag. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAP.2022.3229298

Meng Q, Liu X, Duan J, Zhao Y, Zhang B (2023) Ultra-wideband wearable antenna based on composite materials. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 34(10):861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-023-10174-7

Yang W, Cheng X, Guo Z, Sun Q, Wang J, Wang C (2023) Design, fabrication and applications of flexible RFID antennas based on printed electronic materials and technologies. J Mater Chem C 11(2):406–425. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2TC03736J

Belkheir M, Alami M, Mokaddem A, Doumi B, Boutaous A (2022) An Investigation on the effect of humidity on the mechanical properties of composite materials based on polymethyl methacrylate polymer optical fibers (POFs). Fibers Polym 23(10):2897–2906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-022-4164-6

Wang K, Wang Q, Zou L, Su Y, Liu K, Li W, Song J (2023) Study on thermal protection and temperature of PMMA plastic optical fiber for concentrated sunlight transmission in daylighting. Sol Energy 253:127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.02.015

Adnan U, Abbas Z, Gulistan A, Ghafoor S (2022) Radio over plastic optical fibers–a tutorial and review. J Opt Commun. https://doi.org/10.1515/joc-2022-0064

Alonso Romero A, Amouzou KN, Sengupta D, Zimmermann CA, Richard-Denis A, Mac-Thiong JM, Ung B (2023) optoelectronic pressure sensor based on the bending loss of plastic optical fibers embedded in stretchable polydimethylsiloxane. Sensors 23(6):3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23063322

Guerrero-Mendez CD, De Arco L, Pontes MJ, Segatto ME, Cifuentes CA, Bastos-Filho TF, Diaz CA (2023) Fatigue test on optical fiber angle sensors based on polymeric materials for flexion–extension applications. Opt Fiber Technol 78:103334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2023.103334

Pal T, Aditya S, Mathai T, Mukherji S (2023) Polyaniline coated plastic optic fiber biosensor for detection of aflatoxin B1 in nut, cereals, beverages, and body fluids. Sens Actuators B: Chem 389:133897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2023.133897

Wei Z, Wang Z, Zhang J, Li Q, Zhang J, Fu HY (2022) Evolution of optical wireless communication for B5G/6G. Progress Quantum Electron 83:100398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pquantelec.2022.100398

Zhang W, Cao Z, Wang X, Quan X, Sun M (2023) Design, array, and test of super-low-frequency mechanical antenna based on permanent magnet. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 71(3):2321–2329. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3238643

Koh S, Kosuga S, Suga R, Nagata S, Kuromatsu S, Watanabe T, Hashimoto O (2023) Graphene transparent antennas. Carb Rep 2(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.7209/carbon.020104

Lavadiya S, Sorathiya V, Duraisamy K, Devi DH, Das S (2023) Graphene-Based THz antenna: rudiments, fabrication, and forthcoming opportunity. In: Recent advances in graphenen anophotonics. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, pp 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28942-2_13

Rahman MZ, Rahman M, Mahbub T, Ashiquzzaman M, Sagadevan S, Hoque ME (2023) Advanced biopolymers for automobile and aviation engineering applications. J Polym Res 30(3):106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-023-03440-z

Hussain M, Awan WA, Alzaidi MS, Hussain N, Ali EM, Falcone F (2023) Metamaterials and their application in the performance enhancement of reconfigurable antennas: a review. Micromachines 14(2):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14020349

Dejen A, Jayasinghe J, Ridwan M, Anguera J (2023) Synthesis of quadband mm-wave microstrip antenna using genetic algorithm for wireless application. Technologies 11(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies11010014

Elshaekh DN, Mohamed HA, Shawkey HA, Kayed SI (2023) Printed circularly polarized spilt ring resonator monopole antenna for energy harvesting. Ain Shams Eng J 14(6):102182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102182

Shekhawat S, Singh S, Singh SK (2022) A review on bending analysis of polymer-based flexible patch antenna for IoT and wireless applications. Mater Today: Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.06.401

Marasco I, Niro G, de Marzo G, Rizzi F, D’Orazio A, Grande M, De Vittorio M (2022) Design and fabrication of a plastic-free antenna on a sustainable chitosan substrate. IEEE Electron Dev Lett 44(2):341–344. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2022.3232986

Yin J, Singh R, Chen M, Xie L (2023) Carbon nanotube-based electrically tunable broadband terahertz absorbers. Opt Mater 139:113779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113779

Singh K, Jaiswal R, Kumar R, Singh S, Agarwal K (2023) Polymer-based nanocomposites as defence material. Bull Mater Sci 46(2):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-023-02932-4

Fay CD, Mannering N, Jeiranikhameneh A, Mokhtari F, Foroughi J, Baughman RH, Wallace GG (2023) Wearable carbon nanotube-spandex textile yarns for knee flexion monitoring. Adv Sen Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsr.202200021

Darwish MS, Mostafa MH, Al-Harbi LM (2022) Polymeric nanocomposites for environmental and industrial applications. Int J Mol Sci 23(3):1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031023

Ramasubramanian B, Sundarrajan S, Rao RP, Reddy MV, Chellappan V, Ramakrishna S (2022) Novel low-carbon energy solutions for powering emerging wearables, smart textiles, and medical devices. Energy Environ Sci 15(12):4928–4981. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EE02695C

Balanis CA (2016) Antenna theory: analysis and design. Wiley

Sanjari HR, Merati AA, HosseiniVarkiyani SM, Tavakoli A (2016) Evaluation of the effect of bending on the resonance frequency of inset-fed rectangular textile patch antenna. J Ind Text 46(1):19–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1528083715569377

Zaidi NI, AbdRahman NH, Yahya MF, Nordin MSA, Subahir S, Yamada Y, Majumdar A (2022) Analysis on bending performance of the electro-textile antennas with bandwidth enhancement for wearable tracking application. IEEE Access 10:31800–31820. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3160825

Zaidi NI, Ali MT, AbdRahman NH, Yahya MF, Nordin MA (2020) Analysis on different shape of textile antenna under bending condition for GPS application. Bull Electr Eng Inform 9(5):1964–1970. https://doi.org/10.11591/eei.v9i5.2185

Hasan RR, Saleque AM, Anwar AB, Rahman MA, Tsang YH (2022) Multiwalled carbon nanotube-based on-body patch antenna for detecting COVID-19-affected lungs. ACS Omega 7(32):28265–28274

Song H, Jeon H, Im D, Çakmakçı N, Shin KY, Jeong Y (2022) Free-standing carbon nanotube film for high efficiency monopole antenna. Carbon 187:22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.10.068

Wagih M, Yong S, Yang K, Weddell AS, Beeby S (2022) Printed non-metallic textile-based carbon antenna for low-cost green wearable applications. In: 2022 16th European conference on antennas and propagation (EuCAP), IEEE, pp 1–4. https://doi.org/10.23919/EuCAP53622.2022.9769040

Shao T, Liu Y, Sun L, Xu Y, Kong S, Liu S, Tian S (2022) A dual polarization optical transparent antenna for 5G communication application. In: 2022 IEEE 10th Asia-pacific conference on antennas and propagation (APCAP), IEEE, pp 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1109/APCAP56600.2022.10069198

Suryanarayana V, SatyaAnuradha M, Paul Douglas S (2021) Performance analysis of multiwalled carbon nanotube, composite multiwalled carbon nanotube, and copper-based antenna in X-band applications. In: Microelectronics, electromagnetics and telecommunications: proceedings of the fifth ICMEET 2019, Springer, Singapore, pp 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3828-5_46

Elmobarak HA, Himdi M, Castel X, Rahim SKA, Geok TK (2022) Flexible patch antenna array operating at microwaves based on thin composite material. IEEE Access 10:115663–115672. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3218342

Ziani D, Belkheir M, Rouissat M, Mokaddem A (2023) Design optimization for improving the performance of rectangular antennas using polyimide (PI) and liquid crystal (LC) polymers substrates. Polym Bull. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-05114-8

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the General Direction of Scientific Research and Technological Development of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria.

Funding

This work was supported by the General Direction of Scientific Research and Technological Development of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria. (PRFU: A25N01CU320120230001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contribute, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing intersects

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziani, D., Belkheir, M., Rouissat, M. et al. Design optimization for microstrip antennas based on polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) substrate and carbon nanotube (CNT) conductive material in sub-6 Ghz band. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 13, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-024-00486-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-024-00486-w